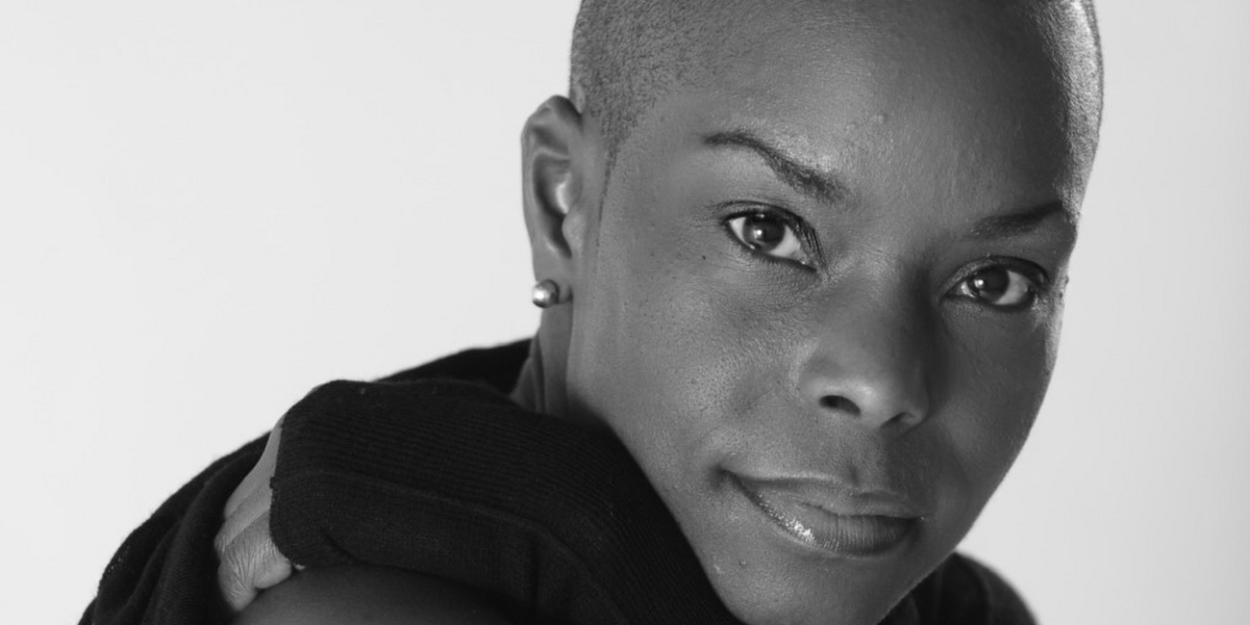

Interview: CORNELIA STREET Choreographer Hope Boykin Talks New York Influence, Dancers vs. Actors & More

Boykin breaks down her choreographic process, collaborating with the cast, and more.

Hope Boykin is one of the premier choreographers in the world today, having choreographed for companies including Philadanco, Dallas Black Dance Theatre, Ballet Black of London, American Ballet Theatre Studio Company, and many more. She is a two time "Bessie Award" winner, an original member of Complexions, and most recently completed her 20th and final year with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater.

Boykin is the choreographer of Atlantic Theater Company's world premiere production of Cornelia Street, now playing Off-Broadway at Atlantic Stage 2 (330 West 16th Street). Featuring a book by Simon Stephens, music and lyrics by Mark Eitzel, and direction by Neil Pepe, Cornelia Street will play a engagement through Sunday, March 5th.

Cornelia Street follows Jacob Towney, whose West Village restaurant is a home to the ghosts of the neighborhood's past. Jacob tries to save his restaurant and give his daughter the life that he dreams she can have.

Cornelia Street features George Abud (The Band's Visit), two-time Tony Award winner Norbert Leo Butz (My Fair Lady), Esteban Andres Cruz (Halfway Bitches Go Straight to Heaven), Gizel Jiménez (Netflix's Tick, Tick... Boom!, Wicked), Jordan Lage (American Buffalo), Kevyn Morrow (Hadestown), Tony Award nominee Mary Beth Peil (Anastasia), Lena Pepe (Off-Broadway Debut), and Ben Rosenfield ("Mrs. America").

BroadwayWorld spoke with Hope Boykin about her process of creating the choreography for a brand new musical!

I would love to learn about your choreographic process. Where did you begin when thinking about the choreography for Cornelia Street?

Well, when I first started talking to Neil about it, he first expressed that he wasn't sure what type of choreography [he wanted], or if in fact he thought it would need choreography. When he described this particular new musical, he said, "It's like a play that sings.. the story has to not necessarily be interrupted by movement." And I was like, "Oh, you mean like wearing makeup, but it looks natural." And he was like, "Yes!" And I said, "Great! I get that!" Now, that was also challenging, but I totally understood. It didn't necessarily need to be what people see as Hope, it just needed to be that the different characters are seen moving in their character's way.

It started off with me, with a plan to try to make things look as natural as possible, but the only way to do that was to really meet the characters and meet the actors and the artists playing those characters, and figure out what they would do. And then in turn, I collaborated with them to say, "Hey, I think we should try this, to me your character seems like this," and then they would say, "Yeah, that's true, and I've also been developing this as my character." Then, "Okay, let's see if your character would do this." And so, everyone has something that's really stylized with them. There are a couple of "numbers", there's a song called 'Dance' where there is a reminiscent moment, where Mary Beth Piel leads, and that moment is that magical, 'we all know the same step!' choreography. But, other than that, everything is really an expression of what each character would express as they are in the musical.

And Neil really allowed me to be a part of not just the choreography, but also the movement direction. I was Movement Director for The Homecoming Queen, which was my first time working at the Atlantic, and Awoye Timpo was directing that, and so I understood that sometimes people just need to move in and out of situations with ease. Neil really has given me a lot of room as a collaborator on the creative team with this project. So, yes, there is choreography, and hopefully there is choreography that you might not notice is choreography. But, the things that you do see, that's me too [laughs].

Can I ask about how your approach to a work differs when you're choreographing a straight dance piece versus choreographing a piece for a work of theatre?

You're going to laugh at this, but a good friend of mine was working with me on a project, and it involved an actor, and he said, "I hope you know that dancers say 'okay', and actors ask 'why?'" And this is true! You tell a dancer, "Hey, I need you to come out of wing 1, hang out here, do this, do this, exit out of wing 2 upstage left," But the actor needs to understand why their character would have that trajectory. They have a backstory that we often don't incorporate into the movement until the piece is finished. There is a development process, the words on the page, and the story is laid out.

In movement, a great deal of the time, the steps, the choreography, the shifting of the shapes, is abstract. There is no movement for the word 'love', there is no movement for the word 'hate', so you have to take that in with the tempo of the music. What are the lights doing? What's the image of your face? How forceful does the movement happen? And those things portray the feeling and emotion.

We have words in Cornelia Street, so I know that the characters are angry, I know that the characters are sad, I know that the characters are telling a joke. There is a 'why?' in that from the beginning. I had a work that just premiered with the Philadelphia Ballet, and I'm working on other projects, and I know the 'why?', but the dancers, the artists in that room don't really get the 'why?' until they learn what their movement language is.

Cornelia Street is love letter to New York. When New York is the setting for a work of art, it often feels like a character itself. How did the setting of Cornelia Street influence the movement?

Well, considering I feel like a New Yorker now, this is year 22, so I think I'm allowed to say that as a transplant here, it just makes sense. There are things that we do. I was actually having a conversation with Simon Stephens, and he's very gestural when he's talking, even when he's watching, he's constantly moving. He's like, "Hope, I don't really understand how you're making this happen," and then I would imitate exactly what he was doing at that moment. And so, really, that's what it is. How do people walk in? How do we look at our telephones? How do we walk in and command a space? George Abud, he walks in the room as William, his character, he looks around, and I'm thinking, "I've seen this man!" Not only on the street, but in a movie, in a sitcom, I've seen these people, I've seen these interactions. The actors are bringing in their love for this city, and the time they've spent here, and then I'm also able to piggyback off of them.

And I would like to say, it truly is a collaboration. I can ask for something on a certain count, but if the actors are in a position that doesn't work I'll go, "Let's fix it." If something is uncomfortable, "Well, let's change that to the other leg." Nothing is absolute, but because there is a structural foundation, that allows for a lot of freedom. And I think that the love for this city comes out. The mentions of where we are, how far you've gone. Are we in a taxi? Are we in an Uber? This is happening today, it's not so far away from us. How do we function? How do we live? It's like you're peeking into a world that you could walk into. You could walk into this café at any moment and feel, "Oh, I've been there, I've seen this, I know these people," and that's also what's wonderful about it.

What is it like for you when you see it go from the rehearsal space to the stage? What goes through your mind?

I have an incredible assistant, her name is Terri Ayanna Wright, and she is absolutely ideal for this because she knows me, she's danced for me, and she knows what is important as far as specifics are concerned. She'll say, "Hope, does this matter? Is this important to you that this isn't happening? Do you want me to remind the cast?" Because once you're in the space - and theatre is a live interaction, the actors and the artists are communicating with the audience - every night is different, on Saturdays and Sundays it's twice, so there are different emotions that go into this really strenuously and emotionally-driven piece of art. So I had to be a little bit more forgiving with myself to say, "Yes, they know what that is, it might not be the same every night, but we're all on the same page."

And because it is living, and it is live, and it should be spontaneous, there needs to be room for freedom. So, I've learned that I can't get too note-based, because then it starts to kill the spontaneity. But if there are issues, if someone keeps bumping into someone, we need to fix that, maybe that's my fault with the spacing, or something choreographically I need to adjust.

And the other thing about walking into the space and seeing it, was that when you're in the rehearsal studio you're on the same level as the artists are when they're working, so you see it very differently. And then with lighting, and they're in costume, and the set decoration, and the dressings, and the scenery itself, you feel like you're in this space so, "Would they really do that movement?" There are times when I'd be like, "Hey, I need to change something," and I'd say it with a smile! So I'd walk into it like, "This is not you, this is me, but it needs to be done." And everyone has just been so incredible. I really do feel like I've got a family in that space.

What are you most excited for audiences to get to see with this show?

I went down the rabbit hole of these incredible artists, I was like, wow, this is an amazing array of people who are so committed to the story they are telling, I just want to live up to that. I want the movement, the choreography, the shifts in space, the things that I've been able to help, I just want to live up to the greatness that is the artists on stage, the artists backstage, the people you don't see, everyone is working so hard. And not to mention, Mark, and Simon, and Neil. Am I worthy enough to really be a part of this group? And I think that it's hoping the audience can say, "Oh, this was a really well-rounded, connected piece." Then I think that I've done what I'm supposed to do. When it feels right, when it feels natural and not forced.

Photo credit: Ahron R. Foster