Frist Art Museum Hosts Exhibition of Multimedia Works by Haitian American Artists M. Florine Démosthène and Didier William

The exhibition will be on view in the Frist’s Gordon Contemporary Artists Project Gallery from January 31 through May 4, 2025.

The Frist Art Museum will present M. Florine Démosthène and Didier William: What the Body Carries, a multimedia exhibition of figurative paintings, collages, and sculptures by Haitian American artists M. Florine Démosthène and Didier William. Organized by the Frist Art Museum, the exhibition will be on view in the Frist’s Gordon Contemporary Artists Project Gallery from January 31 through May 4, 2025.

M. Florine Démosthène was born in New York but spent much of her childhood in Haiti. Didier William, who was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, moved to Miami, Florida with his family when he was six years old. This exhibition explores how immigrant bodies can carry memories and heritage while simultaneously embodying a new, hybrid reality. Through their multimedia works, Démosthène and William—both featured in the Frist’s 2023 exhibition Multiplicity: Blackness in Contemporary American Collage—offer insights into their experiences navigating life outside Haiti while still being informed by the country’s history, culture, and spiritual traditions.

“This project offers an opportunity to consider the connections and departures between the work of two artists of Haitian descent,” writes Senior Curator Katie Delmez. “In a context where immigrant narratives have often been oversimplified in the news media, we hope this exhibition gives more expansive and authentic insights into how their families’ relocations to the U.S. have shaped the creative practices of two artists making their marks on the contemporary landscape, as well as how personal stories shape our communities, survival strategies, and overall vitality.”

Both Démosthène and William often create figures of ambiguous gender and race set within imaginary geographies that evoke liminal spaces—somewhere between here in the U.S. and a homeland left behind. Their depictions of the complexity of personhood through multiple forms reference the divine twins of Haitian Vodou, Marassa Jumeaux, and reflect the artists’ hybrid experiences. Both artists also emphasize eyes in their works as a way of expressing the need to be seen while protectively subverting the judgmental gaze too often cast upon immigrants and other marginalized people. Démosthène animates the eyes of her figures with glitter; William carves hundreds of eyes into the wooden panels that serve as a foundation for many of his works.

The impact of the artists’ familial and cultural connections to Haiti, however, manifests in their art in different ways. Delmez notes, “Démosthène is particularly influenced by Haitian—and by extension West African—spiritual traditions and mythology, as can be seen in the 3D-printed sculptures that suggest shrines and deities in the work What We Know & What We Don’t Know and in the otherworldly aura of her collages.”

Démosthène sometimes surrounds her figures with various motifs that further encourage a spiritual read of her dream-like scenes. “These include representations of African votive sculptures; lily pad-like forms, which the artist considers her version of the floating cherubs seen in Renaissance and Baroque paintings; and glittery translucent rays emanating from figures’ hands like a supernatural spiderweb,” writes Delmez.

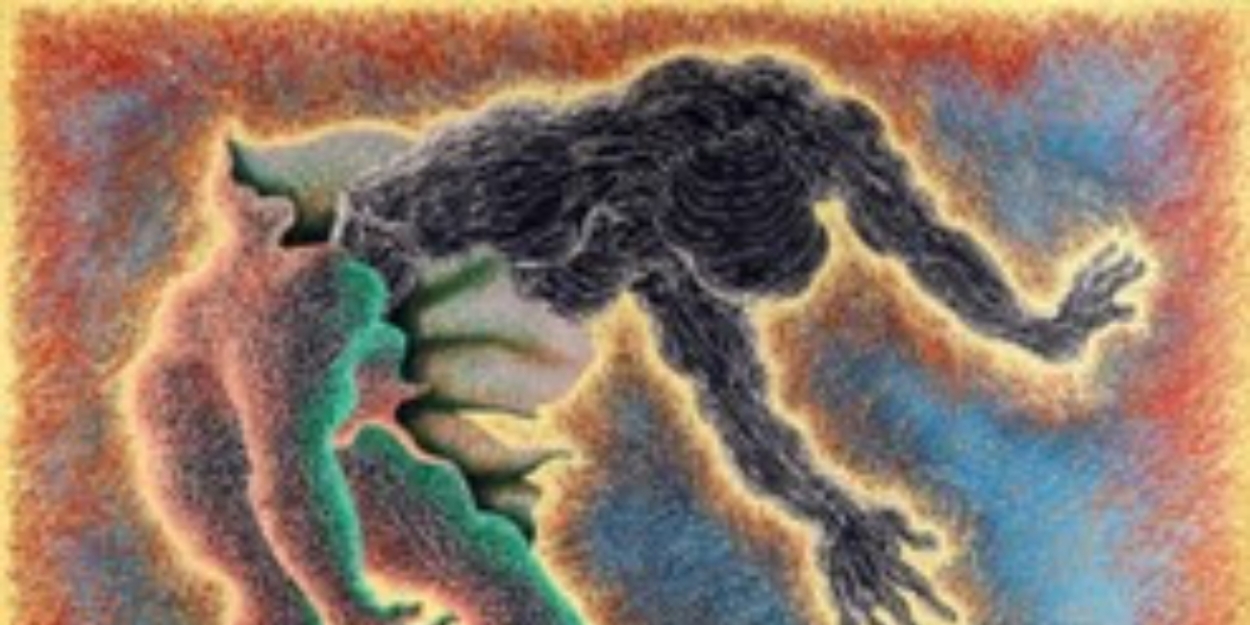

William’s work tends to be more grounded in historical and personal narratives. “Often using his coming of age in Miami with his recently immigrated family as a springboard, William dives into critical inquiries into nationhood and borders, familial memory and mythmaking, violence and tenderness,” writes Delmez. The work Redemption, Resurrection recalls an instance of violent bullying one of William’s brothers endured growing up in Miami. William’s oldest brother ran to avenge the beating; in the work, he is presented as a savior figure with rays of light emanating from behind his body as he fights off assailants.

The process of molting—the shedding of skin or feathers to make space for new growth—appears frequently in William’s work, as in Moult I. Implicit in this visual metaphor is the process of abandoning some aspects of one’s previous life to thrive or survive—a common experience among immigrants.

In the exhibition, selected gallery texts will be available in Haitian Creole, including an essay by Grace Aneiza Ali, a Guyanese-born curator focused on art and migration and an assistant professor in the Department of Art and Art History at Florida State University.

Comments

Videos