Review: Nashville Rep's Stunning and Provocative A DOLL'S HOUSE, PART 2

Nora's back - and she's pissed! Some 15 years after Henrik Ibsen's proto-feminist Nora Helmer came to the momentous decision to leave her controlling husband at the end of A Doll's House - and some 140 years after she first stepped in front of the footlights at Copenhagen's Royal Theatre in 1879 - she finally returns to her Norwegian home to confront her estranged husband and to reveal just what she's been up to since she left her utterly conventional life behind in search of something more.

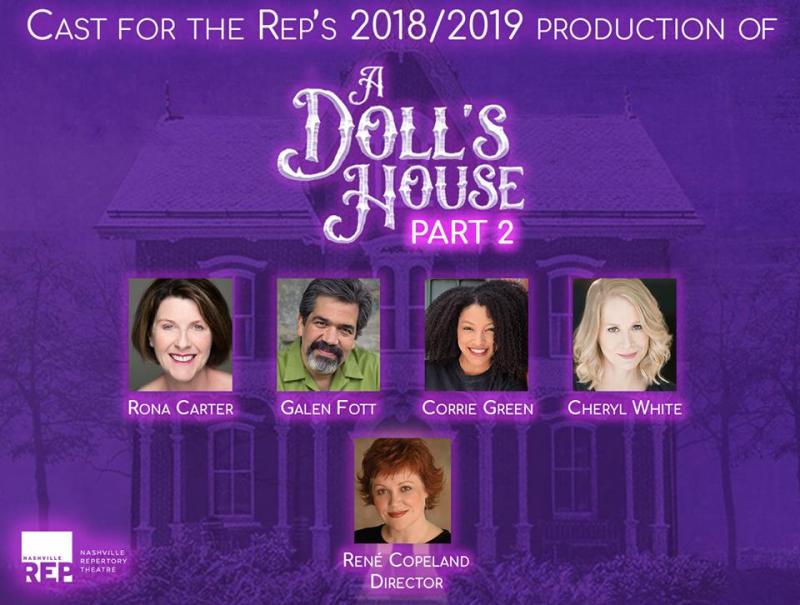

Cheryl White's exquisite portrayal of Nora certainly is reason enough to see Nashville Repertory Theatre's stunning production of Lucas Hnath's A Doll's House, Part 2, now onstage at TPAC's Andrew Johnson Theatre through November 3. But director Rene D. Copeland ensures that this sequel to Ibsen's masterpiece, which attempts to cast Nora's cataclysmic life choices in a contemporary light - Hnath writes in a contemporary vernacular that makes the characters far more accessible than they otherwise would have been - has so much more than just a compelling central character to guarantee that even the most dedicated Ibsenite leaves the theater satisfied after 90 minutes of fiery exposition and engagement, however irreverent it may seem.

More to the point, Hnath's take on what came after Nora walked out that door - and, more accurately, what takes place once she reenters it - will likely leave you with the desire to revisit the original work on which Hnath based his play, in order to compare and contrast and to see just how far afield Nora's journey has taken her. Along the way, you will realize how vibrant the character of Nora remains and how captivating White's portrayal of her is. Nora's fierce persona demands it.

Hnath's play, by turns provocative, enlightening and prescient, is filled with sharp dialogue that keeps audiences riveted to the action that transpires on the gorgeous set designed by Gary C. Hoff and illuminated by Michael Barnett's equally stimulating lighting design. Directed with vigor, wit and focus by Copeland, A Doll's House, Part 2 is eloquent and moving - uproariously entertaining and demonstrably clever to be certain - even if one's disbelief might best be left at the stage door if one is to become totally immersed in the story of what came next for Nora and where she is headed after the final curtain has fallen.

The passage of time becomes an abstract construct in Hnath's play, so effortlessly and gracefully does the 90 minutes spent there seem in retrospect. Credit for that goes not only to the playwright's ineffable ability to write for his characters and his audience, but also to the quartet of actors who perform so impressively under Copeland's expert direction.

The world inhabited by the Helmers in Ibsen's original work is far too conventional for a woman possessed of so much ambition and resolute focus as Nora, and it remains smothering and stifling even as it races headlong toward a new century, even when interpreted by a 21st century playwright known for his creativity and inventiveness.

In 1894, the reserved and taciturn Scandinavians are still loath to accept an ambitious woman, instead suggesting she find self-fulfillment in childrearing and homekeeping, to be the ideal helpmate for a domineering husband, particularly if she has rebelled against the social patriarchy. Hnath's vision of Nora allows her to remain a harbinger of equality to come, an individual determined to live the life she desires, to have the things she wants and to do - if not as she pleases entirely - much as she wishes.

When it premiered, A Doll's House became a cause celebre, the subject of controversy and cultural sensation, eliciting a strong (though not unsurprising or unexpected) response from critics and audiences alike. In Nora, Ibsen created a character - whose aspirations continue to reverberate even in the 21st century - whose impact has proven far more relevant and long-lived than he could ever have dreamed. Hnath's play, therefore, brings to a head the speculation that has surrounded Ibsen's play for the past century and a half by considering the world Nora experienced once she left the relative safety of Torvald's household so that she might see what the world offered a woman like her.

What she found and what audiences witness in A Doll's House, Part 2, indeed may have been much of the same that she'd already lived: married women couldn't enter into contracts without the consent of their husband, they were unable to engage in extramarital relationships and, in many cases, find that their lives would be much easier if they have died and somehow found the secret to resurrection and reanimation. The world's response to Nora Helmer, a thoroughly unconventional woman, is not unlike that encountered by Frankenstein's weirdly stitched together creature when he first came eye-to-eye with humanity. No one knows what to do with her - or any creature, for that matter - designed to confront the pervading morality of a particular era.

That's not to suggest that Hnath's play is not filled with enough crackerjack dialogue and the interactions of its characters to keep audiences practically breathless with each development in the arc of the character or her story.

Nora reenters the Helmer home to discover it is eerily empty, as if the very life had been sucked out of it and, consequently, its inhabitants the moment she left. Gone are the belongings she obviously loved (the loyal, if indifferent, servant Anne Marie tells her that the home is devoid of anything Nora once loved because, well, it was considered hers and, therefore, must be gotten rid of) and there is a pervasive chill in the air that never dissipates even as the choices of the past are confronted one after another as Nora comes face to face with the house's other inhabitants: Anne Marie, the nanny who raised her and her children; Torvald, who is initially noncommittal to and seemingly unperterbed by her return; and her daughter Emmy, whose somewhat benign reaction to her mother's reappearance may simply be because she has no memory of her to elicit a more emotional response.

Nora's life, post-marriage, hasn't been easy (she lived in abject poverty, eking out a meager existence before she embarked on a life far more adventurous than what she had experienced with Torvald and the wee Helmers) and although she has now achieved a certain degree of success - as the author of a slim volume, written under a nom de plume, of prose about a woman who leaves her husband to pursue her own way in life, ultimately dying from her efforts and exploits, it would appear - she remains inextricably tied to the past. If Nora is to achieve self-determination, she must deal with the ever-present skeletons in her closets.

As with Ibsen's original, the role of women and their dependence upon men remains front and center in A Doll's House, Part 2, and Nora once again finds herself threatened with blackmail for a financial fraud of which she may be guilty. When Anne Marie opens the door to reveal Nora standing outside, the light around her envelops her in mystery and intrigue, perhaps portentously suggesting that which is still to come, but Hnath's ability to write sparkling and incisive dialogue for his characters brings even more "light" to the moments that follow. By writing in the vernacular of our world, the four characters easily welcome audiences into their rather fated, if perhaps charmed, circle.

White is superb as Nora, arguing not so much for the equality of the sexes as she does for Nora's freedom to pursue her own individuality. White intelligently refuses to play Nora as a proto-feminist archetype, regardless of her declamations to the contrary, but rather she plays her as a woman oftentimes misunderstood and who, whether she cares to admit it or not, doesn't always understand herself quite so clearly as you would be led to believe.

Clearly, Nora enjoys her new position (revels in it, even) as an arbiter for women's rights in 1894 Norway, yet she never loses sight of her own, more personal, needs and desires - in fact, she comes back to seek a divorce from Torvald, so that she doesn't face the legal ramifications of the possibly illegal choices she has made in her life.

White's Nora is forthright and direct - within the confines of 19th century societal expectations that are fairly palpable even in Hnath's 21st century treatment - but she is also charming, attractive and likable. Dressed in an emerald Green Day gown designed by Trish Clark that renders her beautifully watchable and elegantly sophisticated, White moves about Hoff's spacious set with a confidence and command that is underscored by the sense of unease that surfaces as she reveals more about herself and the life she has been living, which explain the reasons for which she has returned.

Likewise, White's effortless grace as she interacts with each of the other three characters in Hnath's play (arguably, that imposing front door may indeed be the fifth character) is refreshing, revealing Nora's emotions unfettered by flamboyance and theatrical artifice. Instead, White delivers a far more studied, even refined, Nora to best express her motivations, both past and present.

As Torvald, Galen Fott avoids any histrionics or outsized emotions to portray the stoic Scandinavian in a way that might be considered more expected in this day and age - Torvald seems only slightly ruffled by his wife's reappearance, yet as he "unravels" to a point (suffice it to say, he never "loses it" completely, as we'd describe a modern day iteration of the character), he remains primarily unyielding and mostly unchanged, insisting that Nora's life be examined strictly as it relates to his. However, there comes a moment (maybe even a couple of such instances, in fact) during which White and Fott achieve a level of rapprochement when they lie about the floor, tired and spent from an intense argument, that allows them a more immediate and palpable sense of (dare we say it?) friendship. It's a welcome moment that seems unconstrained by social convention, allowing audiences a chance to breathe.

As Torvald, Galen Fott avoids any histrionics or outsized emotions to portray the stoic Scandinavian in a way that might be considered more expected in this day and age - Torvald seems only slightly ruffled by his wife's reappearance, yet as he "unravels" to a point (suffice it to say, he never "loses it" completely, as we'd describe a modern day iteration of the character), he remains primarily unyielding and mostly unchanged, insisting that Nora's life be examined strictly as it relates to his. However, there comes a moment (maybe even a couple of such instances, in fact) during which White and Fott achieve a level of rapprochement when they lie about the floor, tired and spent from an intense argument, that allows them a more immediate and palpable sense of (dare we say it?) friendship. It's a welcome moment that seems unconstrained by social convention, allowing audiences a chance to breathe.

As Anne Marie, Rona Carter again proves why she remains a stalwart of Nashville theater, playing the much older woman with an air of resignation that is framed by her reticence to welcome Nora with open arms, betraying her own sense of loss and abandonment caused by Nora's decision to leave 15 years earlier. Remarkably, Carter ably indicates Anne Marie's reservations and reluctance about welcoming Nora back into the home, even as she expresses gratitude to Torvald for providing her with some security at a time she would otherwise have been set adrift in an unwelcoming, unyielding world.

Corrie Green makes an impressive Nashville Repertory Theatre debut as Nora's daughter Emmy (her sons, presumably, are grown and married and living on their own elsewhere, having dealt with their mother's desertion in equally devastating ways), a matter-of-fact young woman who bristles at any suggestion that her mother's choices have impacted hers, instead opining for an embrace of the traditional in her own life. No matter how admirable she may find her mother's decision to pursue her own path to have been, it's clearly not for her - and she refuses to accept Nora, a virtual stranger, back into her life.

Nashville Rep's production of A Doll's House, Part 2, is elegantly sparse in its gorgeous design aesthetic - Hoff's set, Barnett's lighting and Clark's costumes are impeccable - and the relative economy of Copeland's fluid direction ensures it's yet another memorable addition to the company's 34 years of providing top-flight theater for an audience that is becoming increasingly demanding and self-assured in what they want to see onstage. Bravo.

A Doll's House, Part 2. By Lucas Hnath. Directed by Rene D. Copeland. Presented by Nashville Repertory Theatre at Andrew Johnson Theatre at the Tennessee Performing Arts Center, Nashville. Through November 3. For details, go to www.nashvillerep.org, or call (615) 782-4040. Running time: 90 minutes (with no intermission).

Reader Reviews

Videos