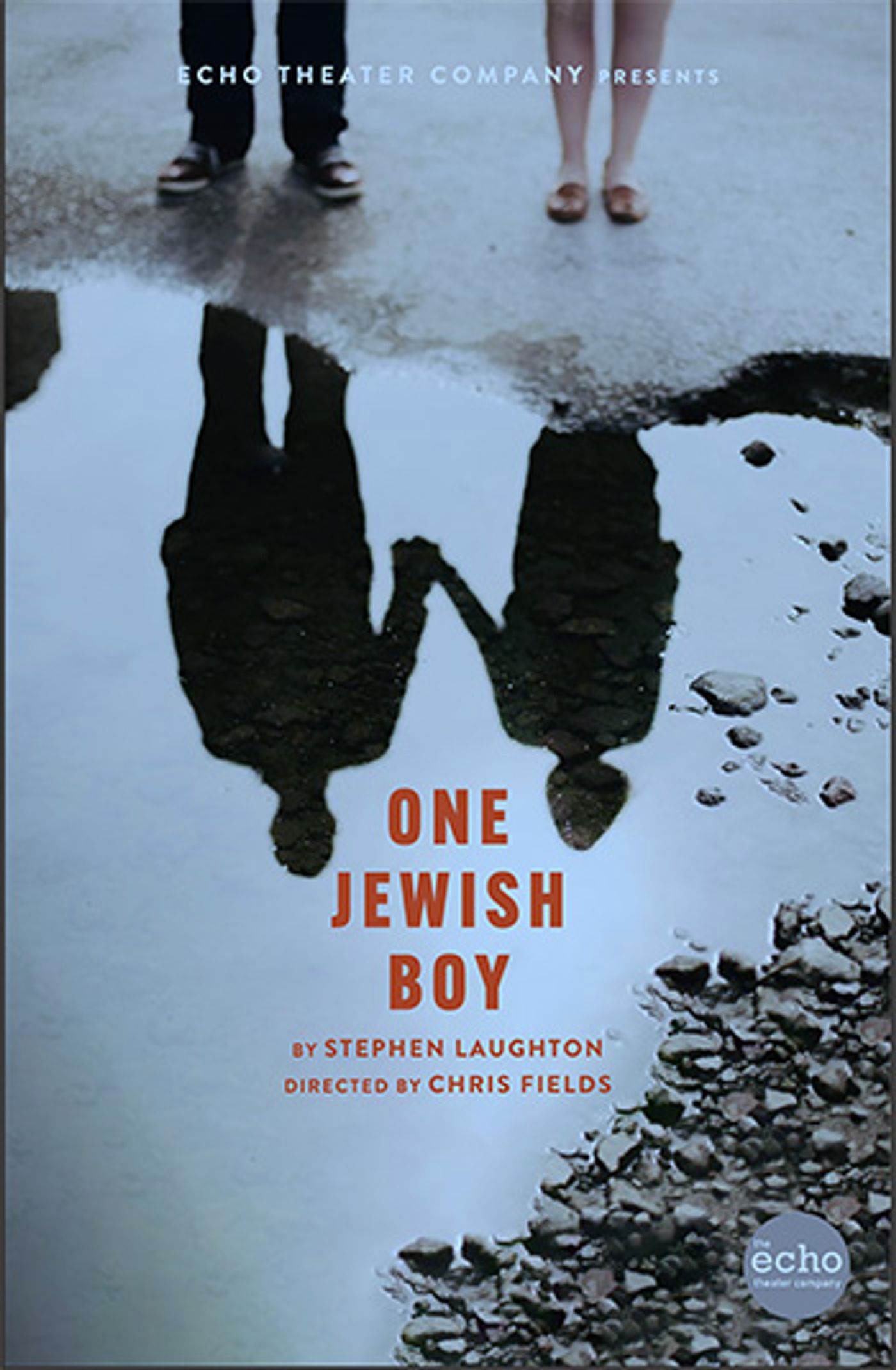

Interview: ONE JEWISH BOY Playwright Stephen Laughton

on West Coast Premiere at the Echo Theatre Company

Navigating any relationship is difficult enough. But what happens when you factor in politics and rising prejudice? Can love survive when opposite political beliefs get in the way? Or is love enough when fear of living fully occurs? Such is the storyline in One Jewish Boy by British playwright Stephen Laughton (pictured).

One Jewish Boy playwright Stephen Laughton

With its West Coast premiere presented by the Echo Theater Company March 22 through April 28, I decided to speak with him about his biting, bittersweet story of two young people in love confronted with the world's unpredictable cruelty.

Thanks for speaking with me Stephen. Is the West Coast premiere of One Jewish Boy your first play to ever be seen in Los Angeles?

Yes, this is the first time one of my plays has been produced in LA, and it’s both a deeply personal and professionally significant moment for me.

To have One Jewish Boy premiere in Los Angeles feels like an affirmation that my work belongs here, that these stories resonate beyond the context in which I originally wrote them. I was at the play a few nights ago, and a bunch of friends came. Literally a quarter of the audience was there to support me. Looking around that room, seeing all those people was overwhelming in the most beautiful way. That kind of love and generosity means everything when you’re in the process of carving out a new chapter in your life.

There’s also something about LA that makes this production feel particularly significant. This is a city built on migration, on hope, on different cultural identities overlapping. It’s a place where people are constantly negotiating their place in the world. That feels very relevant to One Jewish Boy, a play about identity, trauma, belonging, and love in a world that often makes those things feel like they’re in conflict.

Sharae Foxie and Zeke Goodman

Photo by Cooper Bates

You have called yourself a “cynical romantic.” What does that mean?

To be a cynical romantic is to have lived through pain, to have experienced loss, disappointment, and heartbreak, yet still choose to believe in love, in connection, in something beyond the darkness. It is a contradiction, but I think it is a necessary one.

It’s about understanding failure — failing yourself, failing the person you loved, failing all the hope you both had so much of. And trying to learn from it, be accountable to it, for it. Hoping to be better next time. If you’re lucky enough to have a next time. Hoping that love, in whatever form it comes, is still possible. The world is not a binary place. We are people. We carry light and shade within us, often at the same time. We make mistakes. We hurt and are hurt. We lose things we thought we would always have. And yet, we keep moving forward, searching for something good, something real.

It is not about perfection. It is about the willingness to try, to show up, to choose kindness and compassion and forgiveness when it would be easier to attack. It is about understanding that even in our darkest moments, there is still beauty. There is still light.

It’s understanding the entirety of the human experience, and still having hope that the best of it can and will prevail.

Sharae Foxie and Zeke Goodman

Photo by Cooper Bates

How does that influence the writing of One Jewish Boy?

This play is built on that very tension. At the time I wrote One Jewish Boy, I was balancing two “jobs.” By day, I worked in the comms team at a Jewish agency, often responding to real-world antisemitic attacks, drafting statements, handling crisis communications, and witnessing firsthand how antisemitism was rising, year on year across Europe… 34%, 36% up and up…. By night, I was building a life as a playwright. It was a strange and exhausting experience, being immersed in something so immediate and distressing, and then stepping into a different space where I was supposed to think about storytelling and structure.

I did not set out to write a political play. I set out to write a love story… Wait…Is that true? Maybe I did intend a political play. Either way, what was clear is that love does not exist in isolation. It is shaped by the world around it. Jesse’s trauma, his fear, the way it consumes him, those are real things I was seeing play out in people’s lives every day. PTSD is not just something that affects the person who experiences it. It spreads. It touches the people who love them. It isolates. It makes connection difficult, sometimes impossible.

At the same time, I was becoming acutely aware of how little antisemitism was being acknowledged in public conversations about oppression and discrimination. I was seeing it rise, I was working directly with people affected by it, and yet in the theater world, the space I was so deeply connected to, it felt invisible. There were incredible plays tackling racism, homophobia, and sexism etc etc, but antisemitism was rarely part of the conversation. That silence felt both deeply personal and deeply political.

This play is in my DNA. I lost myself in it. It is part of me. It is me. But at the same time, it is a work of fiction. I am both of them, and I am neither of them. It is as much about the external world as it is about my internal one. It has taken a part of my essence, and I will never get that back.

Sharae Foxie and Zeke Goodman

Photo by Cooper Bates

Tell me more about the two characters, their backgrounds, and marriage as depicted in the play.

Jesse (Zeke Goodman) and Alex (Sharae Foxie) come from two very different worlds, and that difference is part of what draws them together. But this is ultimately a play about allyship, about strengthening our coalitions to fight a greater evil. The problem is that they do not always see the nuances of their differences or how many more similarities they actually share.

Jesse is a middle-class Jewish man. He is intelligent, gauche, a smart-ass, deeply loving, but even more deeply traumatized. After experiencing a violent antisemitic attack, his entire inner world collapses. He is no longer just aware of the dangers of the world, he is consumed by them. His PTSD is not just an emotional burden, it is neurological. It rewires how he interacts with the world, how he trusts people, how he perceives risk. It impacts every aspect of his life, including the way he loves.

Zeke Goodman and Sharae Foxie

Photo by Cooper Bates

Alex, on the other hand, is a mixed-race, working-class woman who was raised by her single father. She is pragmatic, fiercely independent, funny, smart, rebellious, wild in her way, but so straight-down-the-line in others. She is used to managing difficult situations. She knows how to keep things together. And she does that for them, for a really long time. Sometimes she is oblivious to the work Jesse is doing, sometimes she sees it all too clearly. But when they have a child, when suddenly she is not just responsible for herself but for another life, the weight of it all becomes unbearable.

Because none of us exist in a vacuum. Oppression does not happen in isolation. For all the ways Jesse and Alex are different, there are just as many ways in which their struggles should align, but they do not always see that.

I am centering antisemitism as the main thrust of the play because that is the story I needed to tell, but Jesse’s pain is not more valid than Alex’s, and Alex’s is not more valid than Jesse’s. They both experience racism, but in different ways. Jesse experiences antisemitism in the form of direct violence, but also through coded language, through erasure, through the way his trauma is treated as secondary, inconvenient, something people do not want to deal with. Alex has grown up knowing that as a mixed-race woman, she has to be stronger than the people around her just to be seen, just to be heard.

Sharae Foxie and Zeke Goodman

Photo by Cooper Bates

She has learned how to navigate her identity. Jesse has not. And that is where the tension in their marriage exists. Jesse’s pain makes him withdraw. Alex’s pain makes her push forward. They do not recognize that their survival instincts are at odds with each other, even though they both come from a place of wanting to protect the life they have built together.

Allyship means doing the hard work of seeing beyond your own experience. Jesse and Alex fail at that. They are so consumed by their own struggles that they do not always recognize what the other person is carrying. And that is not just their failure, it is a failure we see play out in the world around us every day. If we cannot acknowledge each other’s pain, if we cannot build coalitions, then we will keep losing. That is what the play is really about.

What makes their marriage so compelling is that they truly love each other. They are not together because of obligation or convenience; they are together because they want to be. They need to be. Their love is something special. This is the romantic in me — I wanted to write a beautiful storm of a relationship, one that embodies the pure, overwhelming power of love. But sometimes, love is not enough. Sometimes, the world gets in the way. Sometimes, we get in our own way.

That is what the play explores. Not just love, but the things that threaten to break it. The things we inherit. The things we fear. The way we carry history inside us, even when we try to leave it behind. And, most importantly, what happens when we do not recognize that our struggles are interconnected, when we let our pain divide us instead of bringing us together.

Sharae Foxie and Zeke Goodman

Photo by Cooper Bates

You have said that “the fear of hatred can be worse than the hate itself.” How is that reflected in the play? And why does Jesse allow that fear to get in the way of his love for Alex?

I don’t entirely stand by that statement anymore. Hatred is hatred. It’s destructive. It does real harm. But what I was clumsily trying to say is that PTSD changes your relationship to the world. It makes you hypervigilant. It makes you anticipate danger everywhere. That fear becomes bigger than the original event. It shapes your decisions, your relationships, your entire reality.

That’s what happens to Jesse. He’s not just reacting to what happened to him — he’s reacting to the possibility that it could happen again. That fear dictates how he loves Alex, how he parents their child, how he moves through the world. He loses trust. Mostly in himself — he even says it — he says that everything he thought was true about himself just isn’t…. He loses the ability to believe in safety.

And that’s what PTSD does. It isolates you. It convinces you that no one can truly understand what you’ve been through, that no one can help, that you are fundamentally alone. And broken. There really are some traumas that are just too foundational to fully heal from. That’s what makes the play so heartbreaking. Because Jesse and Alex do love each other. But love alone isn’t always enough to pull someone out of their own darkness.

Zeke Goodman and Sharae Foxie

Photo by Cooper Bates

How did the two of them meet? And how did their families feel about their marriage?

This play is deeply rooted in contemporary left-wing progressive Jewish values, both politically and spiritually. Spiritually, in the idea that Judaism evolves through time, continuously reshaping itself in response to the key concepts at the very heart of the progressive movement: Tikkun Olam (repairing the world), Tzedek (justice), and Gemilut Chasadim (acts of kindness). In this context, Jesse’s family loves and accepts Alex for exactly who she is. There is no hesitation, no expectation that she convert, no tension about their relationship.

Alex’s father adores Jesse. He raised her alone after Alex’s mother died. It has been just the two of them for so long, and he is a true romantic at heart. He sees the love that Jesse and Alex share, and he wants that for her. He hopes they can build something deep and lasting together. He has known loss and never wants his daughter to experience that kind of heartbreak.

And then there is the mythos of the play — the question of when and where they met. It’s a mystery that runs as a playful subplot throughout the piece, and I don’t want to spoil it by saying any more.

Zeke Goodman and Sharae Foxie

Photo by Cooper Bates

Tell me more about how the play puts a face on antisemitism, which unfortunately is on the rise in the world.

Antisemitism does not have one face. It is not just one thing. It is attacking people online for saying something Jewish, for advocating something Jewish, for being Jewish. It is holding a diaspora Jew accountable for Benjamin Netanyahu’s expansionist policies. It is the way leftist rhetoric around Israel and Palestine sometimes veers into something more insidious, something that erases Jewish identity or suggests that Jews cannot be victims of racism.

And then, of course, there is the other side. The right-wing nationalism, the swastikas scrawled onto synagogues, the Tech Bros, the Podcast Hosts, the Felons, and the politicians seig heiling at an inauguration. It is the conspiracy theories that claim Jews control the world. It is the attacks on the streets that barely make the news anymore. It is the casual hate, the coded language, the way antisemitism can slip into conversations unnoticed until it is suddenly everywhere.

It is also a political strategy — the distortion of an evangelical theology that claims the return of Jews to the Middle East will trigger a seven-year countdown to Armageddon and the return of Jesus Christ. This religious extremism has been politicized, cynically exploiting Jewish people by claiming to combat antisemitism while weaponizing it to silence criticism. By framing opposition to their actions in the Middle East (any of their actions at all) as terrorism, they establish a dangerous precedent that stifles legitimate opposition.

That’s called fascism.

This strategy has deceived many into believing that its proponents genuinely care about Jewish people. In reality, they will exploit us until they've achieved ethnic cleansing for economic interests, and then conveniently suggest we return to 'Zion.' Remember, Hitler wanted Jews to return to ‘Zion’ too.

Have you worked with director Chris Fields (pictured), artistic director of Echo Theatre Company, before? And if not, how was he selected to direct One Jewish Boy?

I’ve never worked with Chris before. I was introduced to the Echo Theater and to Chris through a member of the Echo board who has been overwhelmingly generous and supportive of me since I moved to California. I quickly fell in love with the Echo. It reminded me why I love studio theater, why I love bold, independent theater. This is where I started. This is why I started.

After an initial introduction, Chris actually selected me and I am so grateful for that. Chris immediately understood the play’s heart, its humor, and its urgency, and he approached it with such care and thoughtfulness. Sometimes with way more care than I do. The rebel in me is like, let’s fuck it all up. He’s like, wait…

What struck me most was how he immediately saw it as a love story first. He let the politics speak for itself without ever losing sight of the intimacy at its core.

Chris’ laser-sharp focus is the sheer force of Jesse and Alex’s relationship. And that is special. He cares so much about them. It is kind of beautiful to watch. There is something really lovely about the team he has built here. It is delicate and sweet and filled with humility, humor, and care.

And that has also been my wider experience of the Echo. I have never felt so deeply welcomed into a theater. I have been really lucky and embraced in my career, but this feels different. I feel exceptionally welcomed and loved and held. I feel incredibly lucky to have Chris directing this production and to be working with such a brilliant team. And I’ll come back any time they’ll have me!

He is also an amazing dramaturg…

Sharae Foxie and Zeke Goodman

Photo by Cooper Bates

Since British politics plays a key role in the play, please describe the political parties/system in the U.K. for those of us unfamiliar with anything other than royalty.

The UK operates under a parliamentary system, with the two dominant political parties being Labour (center-left, traditionally the party of the working class and trade unions) and the Conservatives or Tories (center-right, traditionally representing big business, economic liberalism, and nationalism). There are also smaller parties like the Liberal Democrats, who position themselves as centrist, along with various nationalist and regional parties in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

Labour, when it is at its best, is a party built on socialist principles. Workers’ rights, social justice, investment in public services, and a commitment to equality are at its core. But it has long had an internal struggle between its more radical left-wing factions and its more centrist, Blairite elements. In the late 2010s, Jeremy Corbyn led the party with an unapologetically socialist platform, focusing on wealth redistribution, the NHS, and renationalization of public services. He was popular with the grassroots but faced intense opposition from the media, the political establishment, and even many within his own party. His leadership became deeply polarizing, and while his policies resonated with many, Labour failed to win an election under him. The handling of antisemitism allegations within Labour also became a major issue, further dividing the party and damaging its credibility.

On the other side, the Conservatives, led by Boris Johnson, rode a wave of nationalism, Brexit populism, and media support to secure a massive parliamentary majority in 2019. Johnson’s government was chaotic, scandal-ridden, and defined by its mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic and a general disregard for accountability. But the Tories, for all their internal dysfunction, have been ruthlessly effective at maintaining power.

The Liberal Democrats, meanwhile, have played a unique role in recent British politics, particularly in their 2010 coalition with the Conservatives. Many saw the Lib Dems as the progressive alternative to Labour, but their decision to go into government with the Tories was widely viewed as a betrayal of left-wing voters. They enabled Conservative austerity policies, which gutted public services and deepened economic inequality, while completely abandoning their key campaign promise to oppose tuition fee increases. This decision lost them a huge portion of their voter base. The coalition years shattered their credibility, and they have struggled to recover ever since.

All of these tensions, Labour’s internal fractures, the Conservative Party’s dominance despite its corruption, and the failure of centrism to offer real solutions, form the political backdrop of One Jewish Boy. It is set against a moment where the left is fighting itself, the right is stronger than ever, and hate is being normalized in ways that feel eerily familiar. The play does not just exist in a personal vacuum. It exists in the political climate that shaped it.

Sharae Foxie and Zeke Goodman

Photo by Cooper Bates

What’s next for the play after its L.A. engagement?

Right now, I am just focused on this production and taking it all in. I want to be present with this.

And what’s next for you? A movie, TV show, or another play?

I have two major new plays opening this year, a feature film in pre-production, and two other film projects in development. So it’s been busy…

It has been a wild few years, and I have tried to use the ups and downs to grow my craft. I feel incredibly lucky that I have been able to ride the wave of it all and still be here, still be writing, still doing what I love.

I have theater down, and it looks like film is working out for me too, which is very cool. But what I’m really looking forward to is breaking into U.S. television. Writing can be a lonely job, and the idea of being in a writers' room, collaborating, building something with a team, is something that really excites me.

Chris and I are collaborating on a new Echo project too…so, watch this space….

What do you expect patrons to be talking about after seeing One Jewish Boy?

I hope they see the love. I hope they forgive Jesse and Alex for their worst moments. I hope they see humanity in all its beauty and all its flaws.

I hope they walk away with the understanding that the only way forward is together. That fear and hatred will never lead anywhere good. That we have to lean into the light.

Anything else you would like to share about yourself or the play?

This beautiful team has created something next level, and they deserve all the audiences, all the awards, and all the love for their grace, care, talent, and the sheer heart they have poured into my little play.

One Jewish Boy opened Saturday, March 22 and performances continue Fridays and Mondays at 8 p.m.; Saturdays at 7 p.m.; and Sundays at 4 p.m. through April 28. There will be three Thursdays (April 10, 17 and 24) at 8 p.m. Tickets are $38 on Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays, and $20 on Thursdays. All Monday night performances are Pay-What-You-Want. Atwater Village Theatre is located at 3269 Casitas Ave in Los Angeles, CA 90039.

For more information and to purchase tickets, call (747) 350-8066 or go to https://www.echotheatercompany.com/ Available tickets will be sold at the box office prior to each performance.

Videos