Interview: John Rubinstein Adds EISENHOWER To his Lengthy Resume of Impressive Portrayals

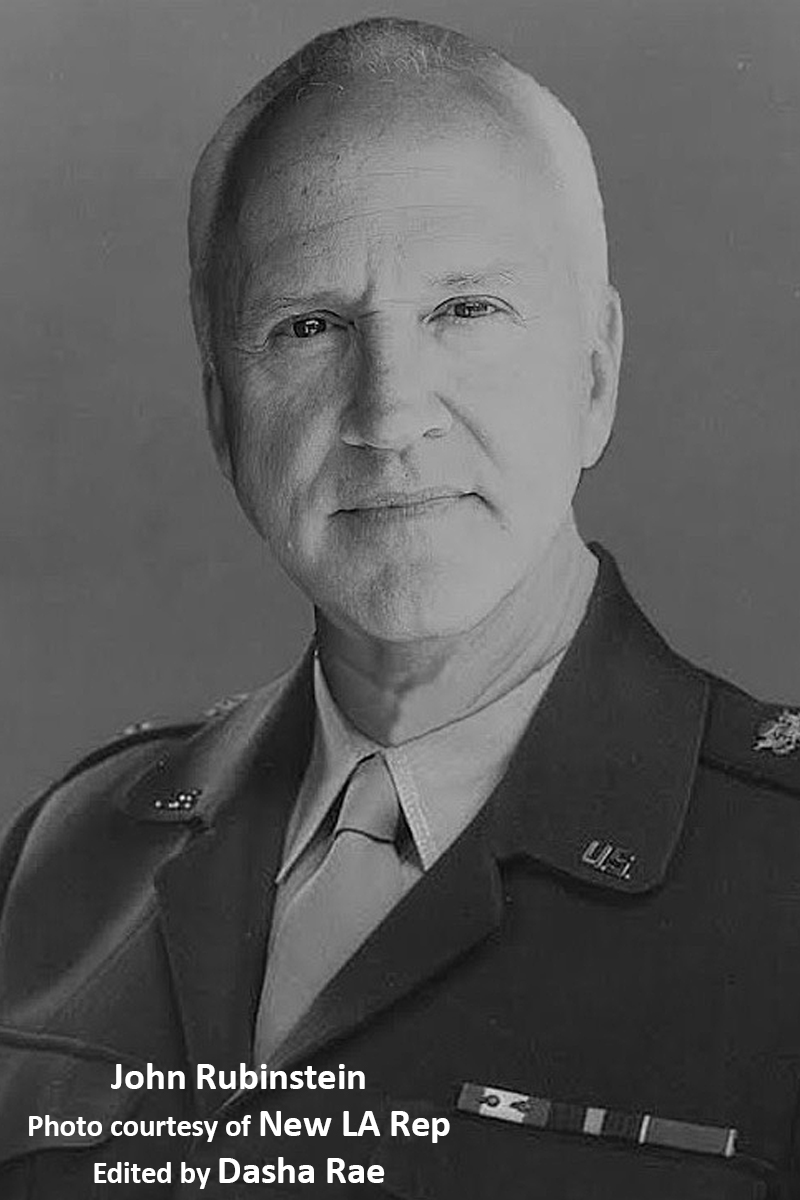

Tony Award-winner John Rubinstein performs in his first one-man show Eisenhower: This Piece of Ground at Theatre West opening October 22nd

Tony Award-winning Broadway veteran John Rubinstein performs in his first one-man show Eisenhower: This Piece of Ground at Theatre West opening October 22, 2022. This world premiere (co-produced in association with New Los Angeles Repertory Company) is directed by Peter Ellenstein.

John carved out some time to answer a few of my queries.

Thank you for taking the time for this interview, John!

What elements of this production attracted you to commit your talents?

I have never before done a one-person play. I find the genre challenging, fascinating, difficult, but often very engrossing and informative and transporting. I've seen many over the years and have often thought that I would like to try it. Never did find the person to portray or the play to interpret -- until Peter Ellenstein sent me this play about Eisenhower. I think the writing is excellent, and I also feel that people need to hear these words from an actual U.S. President during these very trying times that the whole world is going through.

Had you worked with any of Eisenhower: This Piece of Ground's creatives before?

The director, Peter Ellenstein and I met a number of years ago when he was in charge of the William Inge Festival in Kansas, and I was there participating in a celebration of the work of the playwright David Henry Hwang. I had recently appeared in his play M Butterfly on Broadway, and I was delighted to get to revisit that stunning piece of theater in a reading at the Festival.

What would you list as qualities of this man you're portraying?

That list of qualities could be very long. The thing that jumps out most is the man's empathy for other people, whether they are the members of his family, his parents and many brothers, his children and grandchildren, the soldiers he led into battle, the people who influenced him during his education, or, ultimately, all the people of the United States, for whom he was the elected president and spokesman and caretaker and representative for eight years in government; not to mention the citizens of the countries throughout the world where the U.S. had influence and could work to help those nations prosper. We seldom hear, these days, our politicians, or our military leaders, speaking about the jobs before them and the people they work for with the care, understanding, intelligence, and foresight that Dwight Eisenhower had all his life.

What would you see as his flaws?

Even when playing great classic villains, the actor in rehearsal is usually working hard trying to understand the character he or she is playing, to see whatever good qualities they have; or at least see the motivations and reasons that might have driven them down the wrong path. Playing a non-fictional, historical person like Eisenhower, I don't really see an array of "flaws." Certainly one can look at his actions and decisions and see how some succeeded and others did not, and those errors or failures could be perceived as "flaws." But character flaws, bad traits -- those are surprisingly and noticeably absent in Eisenhower, at least from this historical perspective.

In 1972, you made your Broadway debut in the title role of Pippin. What do you remember of your first audition? Song selection? Singing and dancing auditions?

My first audition for Pippin took place in early 1972 in my home in Los Angeles. Bob Fosse came over, I played the piano and sang two songs by the great Laura Nyro for him -- "Time and Love" and "I Never Meant to Hurt You" -- and then we sat on my couch with the script, and he read all the other parts through the play while I read all of Pippin's lines. Later that night he returned with a cassette tape of Stephen Schwartz singing all the songs in the show. He told me to learn the second one -- "Corner of the Sky" -- and come to New York in a few days and sing it (and the Nyro songs, too) for Stephen and Roger Hirson and Stuart Ostrow. I did that; and when I was done, Bob came up to the edge of the stage and said, "The part's yours if you want it."

Was your first curtain call pretty much a blur? Or can you recall distinct elements of your wonderful night?

The first performance for an audience was at the Kennedy Center Opera House in Washington, D.C. Not a blur; a night of hard work and yes, some exhilaration at the audience's very positive reaction. Curtain call was just part of the show, and the next morning we were at work again, trying to make it better. Opening night on Broadway in New York wasn't as much fun. All the critics came that one night in those days, so a great number of seats that had until then been occupied by enthusiastic theater-goers were suddenly all populated by critics with note-pads. Thus much less applause for the numbers, far fewer and shorter laughs at the jokes. The show went well, but one of the dancers poked a contact lens out of my eye early on, and I did the whole show sort of cross-eyed; and there was a huge additional output of stage smoke (just for that one night, for lighting effect) during my first song, which filled my throat with particles and made my singing sound pretty weak and tired. So for me, that particular night was exciting per se; it was my Broadway debut, my dream come true in a huge way that I had never expected. But professionally speaking, a "wonderful night?" No.

Was the Pippin script easy to pick back up when did Diane Paulus's revival in 2014, this time as Pippin's father Charlemagne?

The new script was different in many ways from the script we did in the 70's. The writers had done some serious changing of a number of scenes, some musical numbers were cut, others revamped and re-orchestrated. Plus, I was playing a completely different role. It was a wonderful experience from start to finish. I preferred the ending we'd done in 1972. Still do, even though that original script is no longer issued to companies who do Pippin productions now. But Diane's concept was brilliant, the cast was superb, the acrobats outstanding, and I had the best time playing Charlemagne and not having to hit all of Pippin's high notes every night! Been there, done that! I loved it.

Just your resume of theatrical projects brims with a variety of plays. Do you prefer musicals to dramas?

I'm just a journeyman actor. I started acting in grade school in New York in school productions, plays, skits, Shakespeare, operettas. I hoped to someday be an actor. I became a professional actor in the musical Camelot with Howard Keel in 1965 in a summer stock production. I've been acting ever since, in any venue, in all shapes and sizes of plays and musicals and TV and film roles. I love the work, and each type of show has its own joy and presents its own challenge. Musicals give you that lift from the orchestra; it's a special thrill to sing your heart out with a big band supporting you, and great melodies and lyrics to make music and poetry with. But a straight play has that element of reality, of straightforwardness, of silence instead of music, which offer different kinds of clay to mold and risks to take. No true preference, is what I'm getting at, I guess. Although I must admit, very little surpasses the excitement of listening to an overture behind a curtain before starting up a musical. That's a unique gift when one is allowed to experience that.

Was there a lightbulb moment when you decided you also wanted to direct, making your directorial debut in 1987 at Williamstown Theatre festival with The Aphra Behn's The Rover with Reeve and Kate Burton?

I fell into directing when the dean of the Drama Department at NYU asked me to direct a play there. I did The Three Sisters by Chekhov, and Macbeth a year later. The student actors were extraordinary, and I learned more from them than they from me, I'm sure. When I was asked to act in The Rover at Williamstown, I casually asked Nikos Psacharopoulos, who ran the Williamstown Festival, and who had just directed me in a production at The Pasadena Playhouse of Shaw's Arms and the Man, who the director was. He told me they had just lost their intended director. And I said, almost as a joke, "Well, let me direct it then." I expected him to laugh at my little joke. Instead, he immediately said, "Okay." I was slightly terrified -- this cast was not made up of students! But the moment we started rehearsing, that terror gave way to a feeling of knowing what I needed to do; watching those actors, getting ideas and inspiration and information from them and from the script, making choices and addressing problems, finding a rhythm for the whole piece as well as for small moments, working with the artists who created the sets and costumes and lighting and sound -- all that was so enjoyable and stimulating and fun; it all sort of fell into place. I've never been nervous directing again, and I've done many, many plays and some television as well. I can't wait for the next time.

What gives you the most ratification: Receiving your proppers at your curtain call? Hearing 'It's a wrap' after a grueling, yet rewarding shoot?

For some reason, the curtain calls you ask about don't carry the wonder and gratification for me that you seem to consider a given. The curtain call is the actors returning to the stage to thank the audience. The bow is not about "Weren't we wonderful?" It's about "We're so grateful to you out there for being here to enjoy this evening with us!" It's directed, sometimes choreographed, and it's just part of the show, albeit the very last part. Not such a big deal. The "wrap" after a great time on a film job is usually bittersweet. Sure, it's a good feeling to have done the job, hopefully well, and to have that sense of completion. But it's also the moment of the breaking up of what has most often become a family, a team of workers showing up day after long day to create something the results of which we won't see for months sometimes. But friends are made, a spirit of camaraderie and mutual support is formed, fun and hard work are shared, and that final wrap is, basically, goodbye, and we'll more than likely never all be together again. So, it's satisfying on one level, and quite sad on another.

You also have a lengthy list of acting credits in television and film. If financial compensation were not a factor, which entertainment medium would you concentrate your creativity in?

You also have a lengthy list of acting credits in television and film. If financial compensation were not a factor, which entertainment medium would you concentrate your creativity in?

If I could, I would simply keep doing them all. Composing and conducting film music; acting on stage in plays and musicals; directing in the theater and on film; teaching and directing in universities; I love it all, feel incredibly lucky to have been allowed to do so much of it for so long, and could never narrow it down to just one preferred thing.

You teach at the University of Southern California. Do you find elements of your method of teaching similar to your directing technique?

Sure. I don't really have a "method" of either teaching or directing. I approach the task at hand with everything I've got, whatever that is at any given time. Directing a play with students requires more instruction or explanation here and there, perhaps, than directing professionals. But the basic approach and the things you do and say are virtually the same. So, teaching a class of singers performing numbers from musicals, I am "directing" them in a small piece of a larger show. If it's specifically for an audition, it might not be exactly the same as if it were for the show itself; but those differences are relatively insubstantial.

How old were you when you realized your father was a famous concert pianist?

Very young. He was always playing in the house, practicing, then leaving for travels and concerts. I had his records and knew the pieces by heart. I don't remember a time when I was not aware of what he did.

Your mother was a dancer and writer. With all this artistic influence in your childhood, was there any other career choice?

I was probably going to be in "the arts" no matter what. It certainly was what I was exposed to through my parents, who were great devotees of the theater, the ballet, classical music concerts, museums, and so on. I grew up in New York and went to the theater constantly, all my young life. I guess I could have, perhaps even should have, taken the route of the music conservatory and much more serious musical studies, and gone for a career as an orchestral conductor. I am brazen enough to think that I might have been a really good one. But that will remain the "road not taken," even though, as a film composer, I did get to conduct dozens and dozens of first-rate orchestras in Hollywood; it just wasn't Brahms and Ravel and Stravinsky and Mahler in a concert hall -- it was my own stuff, in a recording studio. Not quite on the same level.

What's in the near future for John Rubinstein?

Trying to keep working as much as I can. Always hoping and looking for that next job. That's the story of my professional life, more or less. Most of all, enjoying my happy marriage and my five wonderful, extraordinary children, and my four fantastic grandchildren, my life-long partners in my sisters and brother, and my large extended family and close friends. It is they who lift my spirits and make me look forward to each day.

Thank you again, John! I look forward to meeting your Eisenhower.

For tickets to the live performances of Eisenhower through November 20, 2022, click on the button below:

Comments

Videos