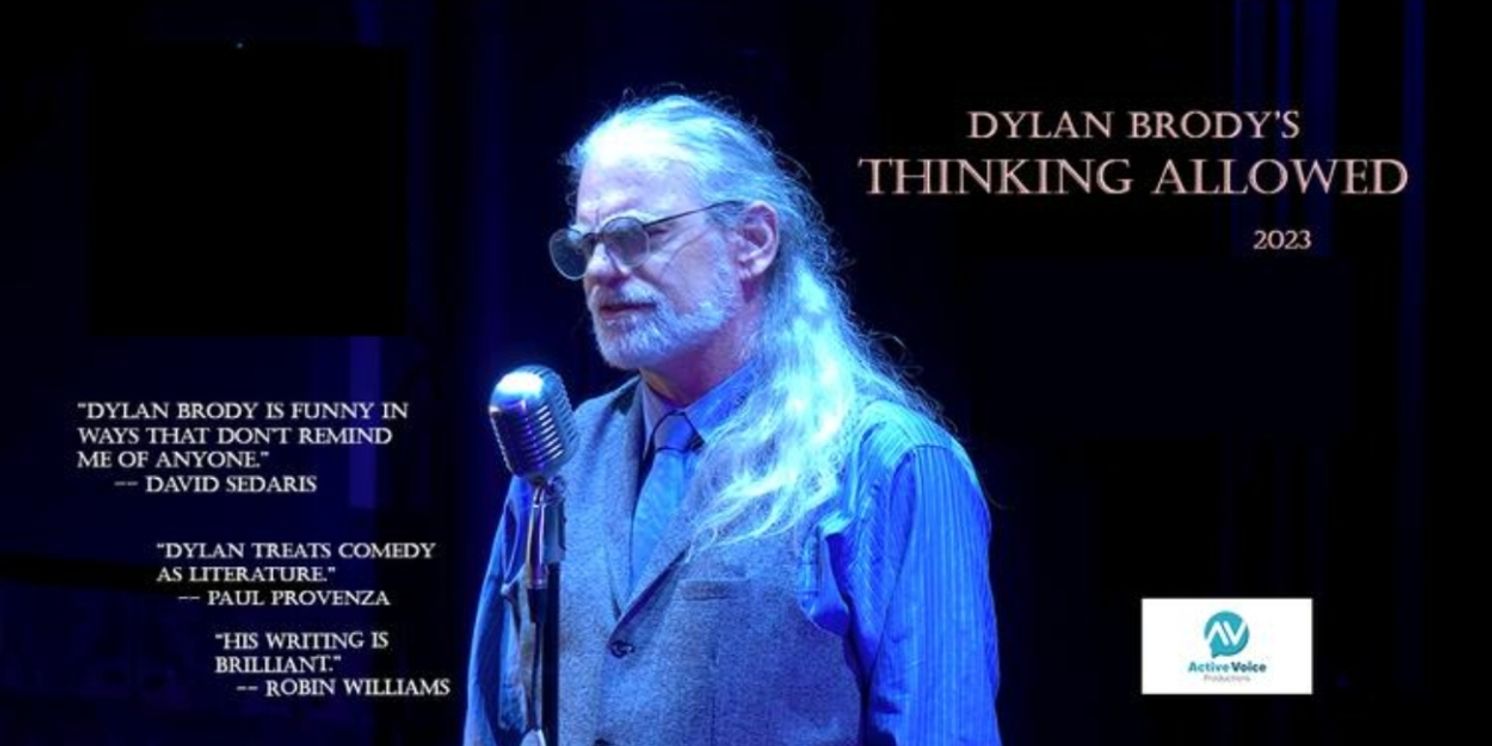

Interview: Dylan Brody of THINKING ALLOWED

He's been a regular contributor to The David Feldman Show on KPFK and the Huffington Post.

For decades, the multiple award-winning storyteller, humorist, playwright, and bestselling author, Dylan Brody, has honed his unique voice, blending insightful observations with sharp wit and a touch of the absurd to earn him a devoted following and the respect of comedic legends including the late Robin Williams and George Carlin.

For three years, the inimitable David Sedaris invited Dylan to share the stage with him during his West Coast tours. His work transcends genre and format. From his full-length, award-winning stand-up style specials like Driving Hollywood on Amazon Prime to the innovative, pandemic-era Zoom series The Corona Dialogues, Brody consistently delivers work that resonates both emotionally and intellectually.

He's been a regular contributor to The David Feldman Show on KPFK and the Huffington Post. His talent extends to writing for others, including Jay Leno. But Brody's reach is far beyond the stage and screen. He's written many plays including Mother, May I, that earned him the prestigious Stanley Drama Award in 2005.

His book A Tale of a Hero and The Song of Her Sword has become a fixture in public school curricula. He has graced venues around the world, appeared on A&E's Comedy on the Road, and was invited to speak at the George Carlin Tribute at the New York Public Library. He was Northfield Mount Hermon School's first Artist in Residence. His fantasy novel, Merlyn's Mistake launches September 30th by Danu Books and his website, DylanBrody.com, is a magical breadcrumb trail that winds through a seemingly endless wealth of literary, audio and video material. He's currently touring with his new show, Thinking Allowed.

JS: Your Zoom project, The Corona Dialogues caught everyone's attention— and a lot of awards. How did the idea first come about? Was it a sense of necessity, or did you see a unique artistic opportunity in the limitations of the format?

DB: Corona Dialogues came about because there was a pandemic. A book of mine, Relatively Painless had a contract – it was supposed to be my first traditional publishing contract and while the advance was teeny tiny, it included provisions for proper support for a book tour. So, it felt as though, at long last, someone was investing enough in one of my things that I might really build a base and a readership. The first iteration of the Grunman Family, the one in both Coronal Dialogues and Relatively Painless and now the weird compilation movie, LockDown 2o2o that’s been winning awards, all came out of my 2005 Stanley Drama Award-winning play. Mother May I. With the pandemic, the book tour was cancelled as was the contract because they really only bought the book thinking my tour might make it big. They went out of business shortly thereafter and my book reverted to me. Rather than sinking into depression and going back to square one with queries and submissions, I self-published and wrote a little video-conferencing play that I could do with my friend Kate Orsini to maybe promote it a little. After we shot the two acts of the short play, she came to me with a third segment. I had never seen someone write something in imitation of my style before like this and it delighted me. Also, hers did not have the character I played in it. I realized she’s not only a terrific writer, but also a way better actor than I. The moment I thought about making Lindsay, the older sister, the center of the piece, I had new ideas for segments to write. I thought we were done after five episodes about the siblings, then Black Lives Matter became a real movement and there were more things I could say through these two, so we started in again. She wrote some. I wrote a lot. I let other friends write episodes, had some terrific guests. Bonnie Hunt dug the work and logged in to play Daniel’s manager and then became a partnered producer. I’m really proud of all the work we did there, but genuinely just blown away by Kate. She became my muse and my purpose during some dark, dark times and I so rarely find a creative who not only keeps up with my rate of productivity but challenges me to the extent that I feel joyously competitive and sometimes outpaced.

Your work explored the absurdity and the shared anxieties of the pandemic era. What elements of the series do you think connected deeply with audiences, and why?

Sure. Some of it was just the timeliness of doing a series about the weird medium-close-up experience of life through video-conferencing that we all experienced during the lockdown. I’m not sure a lot of writers or producers – certainly not comedy writers – really showed a willingness to talk about the general existential threat we all suddenly felt and I did that through the lens of warm, comedic characters whom I’d already explored and developed extensively, so I had an advantage there as a creator. Mostly, though, I think, the two-panel framing of ZOOM provided this static, non-distracting theater of the face in which both performances show constantly – both listening and speaking, reacting and choosing not to – in a way we’ve not seen before theatrically or cinematically. The film showed on the big screen for a festival in Long Beach or something. I don’t remember. All I remember is that it really doesn’t work for me on the big screen. It should be seen on a small screen, leaning in where the resolution is good and we feel like we’re eavesdropping on someone’s ZOOM calls, not huge and blurry and as though someone’s ZOOM calls have been captured and put on display for us. I have an idea for a theatrical play version of the thing, too, that captures live, isolated performances on stage and puts them on giant ultra-high resolution panels above so that we get the tight intimacy and the separate spaces with the separate actors in their isolation. I think the on-camera/off-camera dynamic gives some more dimension to play with.

You're known as a master storyteller with a dynamic stage presence. How did you translate your personal style and charisma to the constraints of Zoom?

I shift from one milieu to another pretty easily. I have pretty strong craft as an actor, though I don’t work very hard to be cast as such. I went to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London for the last year of my Sarah Lawrence College BA in theater. I worked the New York comedy clubs all the time I was in college – got in at the IMPROV in Hell’s Kitchen when I was seventeen. So, working the medium-close up of Zoom is really just a particular exercise of that craft, allowing all the character work to live in the persona Daniel – my character in the series – takes on when he has to talk to his sister. My work as a solo performer, as a story-teller doesn’t feel much to me like acting, though of course it is in at least some ways. Still, once I’m really on a script working with another person who depends on me, not just an audience whose dynamic is very different from a fellow performance, the nature of my focus and my intention changes. I expect the audience to be confused as to what’s authentically me in the moment and what’s on-the-page written material. I expect something very different from scene partners.

Humor can be a powerful tool, especially in dark times. How did you strike the balance between finding the lighter moments within the pandemic and acknowledging the real struggles people were facing?

Comedy gives room to speak the truth even on topics that make people uncomfortable. It’s a bellwether for that which we repress in the zeitgeist. Anyone who went to a comedy club in the seventies or eighties knew that Priests diddled kids, that Boy Scout Camp provided predators the preadolescent prey the sought, that police shot first in black neighborhoods as opposed to white ones. The laughs in the room made it clear that the confessions and observations of the damaged wits on stage spoke truths recognized by enough to be common experience. Richard Pryor did a piece about getting pulled over as a black man and bringing out his wallet in slow motion for fear of being summarily executed. My mind naturally writes jokes in real time as a coping mechanism. Often one needs to create humor is a willingness to speak allowed the shared secret, to say the naughty thing whether it is “fuck” (every comic since 1981, a lot) once taboo in public or “If Jesus walked into St. Patrick’s he’d be held back, shoeless… in a dress… and he’d see a priest wearing a ring worth five grand…” (Lenny Bruce in the early-sixties). During the lockdown we all faced our own mortality in a new way, we feared at some level the end of our civilization, the collapse of our society. Everybody found ways to cope. My way was to write funny scenes about the family frictions coming up in this time of existential dread. When I blurt out the funny in real time, sometimes I offend people. Sometimes I get it right. More accurately, I guess, some people find it funny and authentic, others find it insensitive and wrong-headed. That’s the risk of the creative process. In this case, it seems like those who found the work, dug it immensely.

The Corona Dialogues featured an impressive ensemble cast. How did the experience of remote collaboration shape the project? Did the isolation of the time bring a unique energy to the performances?

There was no way I could have gotten a cast like this to show up and work on the project in person for no money as a virtually unknown producer/director/writer. The unique circumstances of the lockdown combined with the convenience of shooting from their own homes made it possible for me to bring some extraordinary actors on board for the thing. Bonnie Hunt joined us from Chicago. Tovah Feldshuh from Florida. I also had the opportunity to have my father play the role of the closeted gay patriarch, his first acting gig since 1958’s The Plaster Bambino (Sidney Michaels) in which he co-starred with Vivica Lindfors and Burgess Meredith. His performance was wonderful.

Filmmaking on Zoom undoubtedly presented obstacles. Did any of these limitations lead to creative breakthroughs that you might not have discovered otherwise?

The quality of the video and the editing improved dramatically over the year or so of production. For the first several episodes, Kate used her phone to record and for reasons we could not diagnose, it consistently delivered me an image rotated ninety degrees on my monitor. I had to start editing each episode by creating a separate video track just to turn her face right way up. I learned a shit-ton about the editing process in making it and came out of the pandemic properly knowing how to use Premiere Pro, a skill that’s been serving me mightily since as I put together new Dylan Brody Experiments all the time. (activevoiceproductions.com/dbexperiments)

How did the experience of creating The Corona Dialogues influence your understanding of storytelling, of reaching an audience, and potentially even of yourself as an artist?

This project reminded me that there’s great joy in collaboration and as we emerged from lockdown led directly to the financially catastrophic decision to put up a play that was then cancelled because of an Omicron spike opening weekend. Collaboration is good. Deep personal financial investment not so much.

You've now returned to the stage with your live show. How does it feel to connect with a live audience again after the virtual experience?

I love live performance. The sensation of owning a room, whether it comes from the sound of their laughter or the silence when they listen, rapt, really puts me in a particularly comfortable headspace. Whenever I’m away from the stage for a while I start to feel as though I don’t need it anymore and the fact that I spend that kind of time on other things, I suppose, means I don’t. Still, when I get back under the lights with a microphone I remember the great joy and the deep down pleasure of doing one of the things it feels I was born wanting to do.

Having explored and succeeded in so many different forms of storytelling, what are you curious about next? What kind of project pulls at you, making you say, "I have to explore this next"?

With my latest solo show, I incorporate music into my work. That was more than just – hey, it’d be fun to do some of my songs. Musical performance has long terrified me and part of my practice as a performer and a creator demands that I challenge myself to dare create things that make me uncomfortable, afraid, that challenge my own sense of what I can reveal, how vulnerable I can become, how honest. I don’t feel as though that exploration has run its course. I’m still not fully comfortable onstage when I sing. I just finished my first filmic job as a hired-in director and found that incredibly satisfying and interesting which rarely occurs with a project not of my own inception, so I think there may be more directing in my future as well.

For more information about Dylan and his marvelous work visit DylanBrody.com.

Videos