Review: Stunning MISS SAIGON Revival at Segerstrom Center Can't Wipe Away Its Outdated Problematic Motifs

Honestly, I'm a bit conflicted writing this review.

As a fan of musical theatre, I am frequently in awe at the sheer brilliance and stage craft it takes to put on such epic shows. But as an Asian-American who longs for more frequent and more positive representations of our diverse communities in pop culture and the media, I am often disappointed at some of the pervasive and unfortunate stereotypes that still manage to eek out with little forethought in some of today's entertainment productions, especially when non-Asians are the authors of these said works.

2019 marked the year that the first national tour of the 2017 Tony Award-nominated Broadway revival of Cameron Mackintosh's MISS SAIGON finally landed in Southern California, where the show first spent several weeks in Los Angeles at the Pantages Theatre, and has now made its way back to our coast, this time at Orange County's Segerstrom Center for the Arts in Costa Mesa through October 13, 2019.

The musical's original production---which first debuted in the West End in 1989 before transferring to Broadway in 1991---became a global hit despite some loud, very understandable controversy. Most audiences, however, ignored the accusations of orientalism, misogyny, and white-washing and instead focused on the show's epic melodrama and theatrical splendor, much of it powered by the lush music of Claude-Michel Schönberg and the lyrics by Alain Boublil and Richard Maltby Jr. (Schönberg and Boublil famously teamed up before to create another behemoth hit musical, LES MISERABLES).

And then there's also the fact that it's a show that calls for many actors of Asian descent to perform musical theatre---a very rare occurrence that deserves the Asian community's attention, and, by extension, our monetary patronage.

MISS SAIGON, though, was originally conceived to be a more modernized musical theatre update of sorts of Giacomo Puccini's 1904 opera Madame Butterfly, now set during the Vietnam war, a contentious time in our nation's history that found young American men in the 1970's drafted to fight a perplexing, seemingly doomed war on foreign soil. And like the opera that inspired it, MISS SAIGON also shines a spotlight on the hardships and heartbreak of a young Asian girl who gains---then loses---an American lover.

Stories like the one featured here aren't, of course, new in the stage lexicon. A romance narrative that involves two people from opposing cultures is quite a reliable go-to for not only its implied conflicts, but also the surface differences each participant brings to the table, and the reactions and responses that such relationships elicit from people in their environments. Everything from ROMEO AND JULIET to THE LITTLE MERMAID have tackled this territory.

But MISS SAIGON also mixes in additional time-tested tropes wrapped around its epic stage spectacular that are, I'm sorry to say, just as problematic back in 1989 as they are now in 2019.

30 years after its stage debut, experiencing MISS SAIGON nowadays exposes just how outdated and out-of-touch it is with our increasingly diverse world view.

Granted, many of us have probably seen this show a handful of times before, and didn't react so strongly and so viscerally about its objectionable material until recently. My best unscientific guess is that, perhaps, because theatergoers in Southern California (and, well, me) have been exposed to a plethora of recant Asian-themed stage plays and musicals that are far more flattering and less offensive to our culture, that the pre-existing flaws of MISS SAIGON have become increasingly amplified in the juxtaposition.

From ALLEGIANCE and CAMBODIAN ROCK BAND, to SOFT POWER and VIETGONE---with deeply personal, thoughtfully engaging scripts often written by Asian and Asian-American Playwrights themselves---a few shows (which ideally should be more) do exist to prove that it is possible to not portray Asians and Asian-Americans as the merely unfortunate stereotypes that have been so broadly painted in MISS SAIGON.

This is why I am so torn over MISS SAIGON.

I have to say, I cringed a lot during the show---even as part of me was in awe of the show's remarkable entertainment savvy and its undeniably talented, gorgeously multicultural ensemble cast.

On one end of the spectrum, the musical has its multitude of positive aspects, which continue to cement why many love this show. I can make the case that most of those that fanatically love the show are non-Asians who are more apt to dismiss or not even notice the unfortunate bad stereotypes in the show, but that is---like the show's portrayal of the Vietnamese---an untrue generalization.

First, and purely on the surface, the massive musical---directed by Laurence Connor---is absolutely stunning, and even more so, I'd argue, with this new revival, which I first experienced on the big screen when the pre-Broadway London production was streamed in cinemas. When the posters describe the show as an "Epic," you'll believe it on production values alone.

Every bit of technical splendor brought forth by this new touring iteration is undeniably top-notch, from the inspired pairing of Bruno Poet's lighting designs with Luke Hall's projections to Mick Potter's enveloping sound design that keep scenes lively and immersive. Andreane Neofitou's costumes seem realistic to its locale and is time-period authentic, while the impressive set design conceived by Adrian Vaux and implemented by production designers Totie Driver and Matt Kinley is a visual feast.

Oh, and the show's infamous helicopter sequence in Act II? It is a jaw-dropping scene of pure theatrical magic.

The music, of course, remains MISS SAIGON's most memorable aspect and sounds as sweeping as ever, featuring orchestrations by William David Brohn, that is conducted for the tour by musical director Will Curry. The show's ballads "

Secondly, another of MISS SAIGON's many positive traits is a very selfishly motivated bullet point: this musical---despite its perpetuation of stereotypes---has consistently been a reliable employer of talented Asians and Asian-Americans working in the musical theatre.

With representation so minuscule for Asians in Western-made entertainment projects in general, having a show populated with a mostly Asian cast---playing significant, albeit problematic Asian roles---is still a cause for celebration even today, especially with this musical's casting sins (ahem, Yellowface) of the past (I'll give you a moment to Google what I mean). I'm sure it is a sacrifice to one's personal beliefs to set those objections aside in favor of a highly coveted job and the chance to work in the arts (and, yes, the parallels to the Saigon ladies in the show having to put up with something they have objections to in order to survive isn't lost on me).

The original production famously introduced the world to eventual Tony Award winner Lea Salonga (whom I fangirled over during my youth in the Philippines before she even got the London gig). Since that auspicious debut, countless other actors have certainly benefitted from the musical in this manner, inspiring many Asian-Americans to give a career in the arts a chance. The 2017 revival even showered its newfound star Eva Noblezada with a Tony nomination in a role that she, too, carried over from the West End.

For the current national tour, the astonishing Emily Bautista---who made her Broadway debut as the understudy for this same role in the revival---plays the central character of Kim, a relatively innocent 17-year-old Vietnamese orphan who is forced into a new life of working at a seedy bar filled with scantily-clad ladies that mostly caters to horny American troops who grope and grind their way with every girl in the place. The bar is run by the show's manipulative and oily "Engineer" played with wicked glee by the superb Red Concepción.

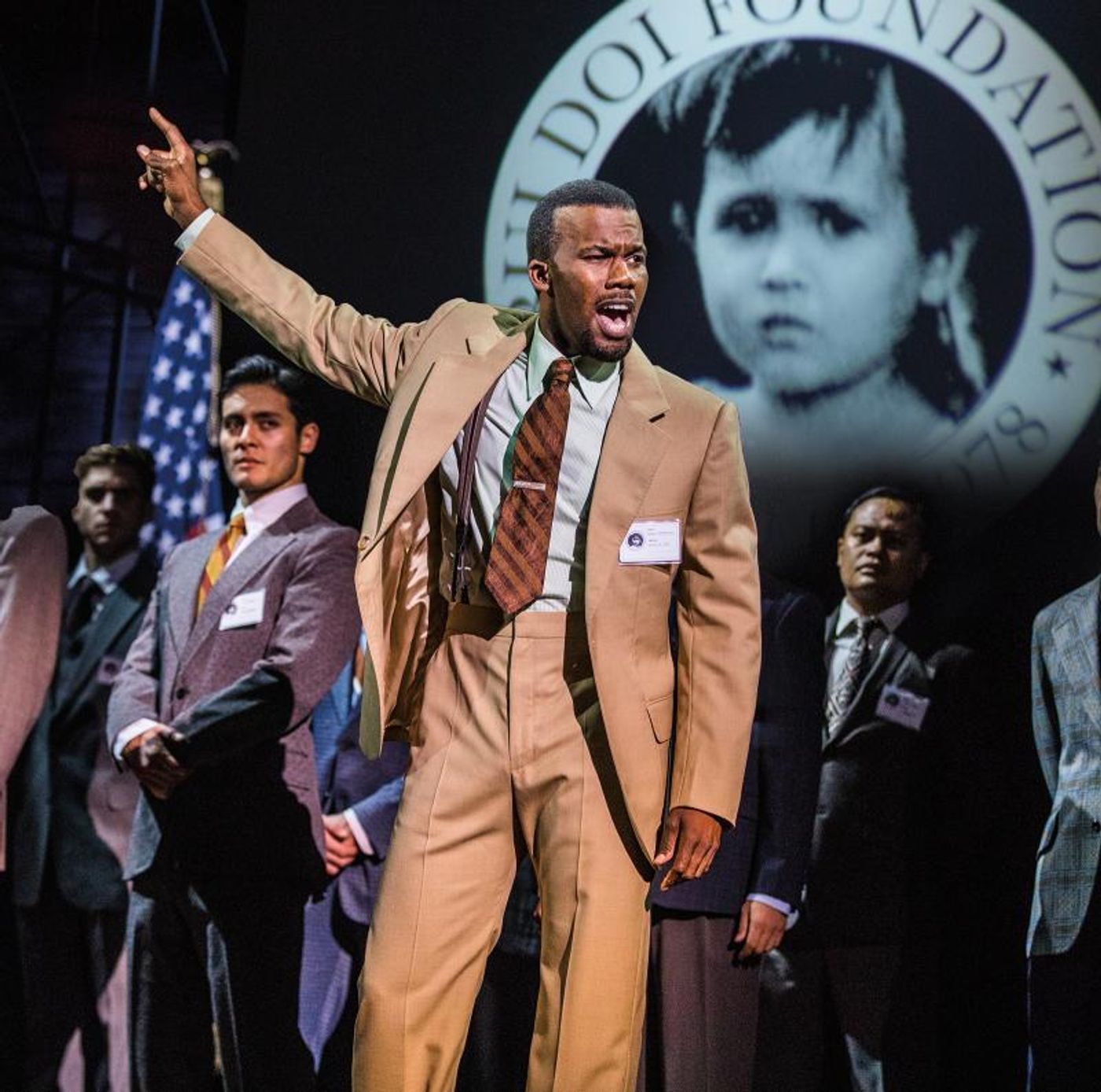

The beautiful singing voices don't stop there. Anthony Festa is impressive as Chris, the less douchey of all the American Marines and the one who falls in love with Kim at first sight. J. Daughtry's strong power vocals as John match his character's strong personality.

Other standouts in the cast include Christine Banuan who brings a genuinely moving and emotional performance in "The Movie In My Mind" that also gives audiences a nicer break from the bacchanal that erupts just a moment before. Ellie Fishman's lovely singing voice gives life to her role as Chris' eventual post-War wife Ellen. Jinwoo Jung's raging Thuy is effectively aggressive. The rest of the ensemble members provide excellent vibrancy and liveliness to the show as written, singing and dancing up a storm. Choreographer Bob Avian provides them with plenty of impassioned moves to keep things electric.

But as wonderful and hardworking as this ensemble cast and the show's creative team have been to make MISS SAIGON genuinely entertaining, their sweat equity isn't enough to shield audiences from the show's unfortunate flaws.

So what is so objectionable about a purposefully sweeping love story that's got many in the community still so heated?

Is it because it is yet another Asian-set fantasy narrative authored and warped from a Western/European point of view, filled with broad and unflattering generalizations about an entire race of people? Is it because said story portrays Asian women as only either hyper subservient or hyper sexualized while the barking Asian men are all apparently manipulative, power-hungry, and prone to violence? Oh... and that it takes valiant American heroes from far away to tame them all and to introduce to them the Western ways?

The offenses start early. The show opens with a song that describes Vietnam as a "hell" on Earth---at least for the visitors to this strange land---and yet the American men have no qualms about objectifying and taking full advantage of the "exotic" female treasures Vietnam has to offer. It's made clear that the Marines have arrived already armed not just with guns but with the attitude of superiority over a country that needed to be conquered.

The ladies put on a great show for the invading foreigners. So how do these bar dancers deal with the handsy, perverted men that frequent their workplace? Oh, they power through it by distracting themselves via their imagination---picturing a better life in cinematic form. Yikes.

To keep this narrative track going, the Vietnamese in MISS SAIGON are portrayed only as less than---prostitutes, criminals, immensely poor, uneducated and unsophisticated, and needing to be either tamed or rescued. This view that third-world countries are populated by "savages" is as old as dirt and so is the idea of the "white savior" swooping in to make all things better.

And lo and behold... in comes handsome, heroic Chris, who, um, beds a 17-year-old girl the very same night they meet (but it's okay because he refused all the "skanky" girls and went for the pure, kind, and innocent-looking one). They declare love for one another. She sees him as her ticket out of this mess of a life, he sees her as someone that could benefit from his privilege.

But as Saigon inevitably falls---leaving the country and its citizens in turmoil even more than before the Americans set foo there---Chris is able to escape, but without his lover. For the next few years, he is haunted by his not-good deed. He feels super guilty, because he promised her that she would be leaving with him, but in the chaotic mass exodus he didn't even get a chance to say goodbye.

Hey, remember... Chris is the good guy. Chris is the good guy who, years later, has guilt-ridden sweaty nightmares about leaving the embassy in a helicopter while thousands of Vietnamese cry out in anguish at the gates below.

Meanwhile the evil Engineer---the embodiment of an old school Asian trope of a snickering character that they had to get a white guy to play him in the original production---thrives by scheming. Every step of his journey involves using Kim to propel him forward. As Saigon falls, he fixes things so that they can leave for Hong Kong with her... and her new son.

Oh, yeah...surprise! Kim's got a son named Tam (played by Haven Je during the Press Opening).

Years later, as Act 2 begins, the now philanthropic (!) John is singing his (okay, gorgeously sung) plea for Americans to have pity on the many "abandoned" children of Vietnam called "Bui Doi"---hundreds and hundreds of illegitimate children fathered by American soldiers while stationed there. Through his organization, John informs the now married (but still, you know, haunted) Chris that, uh, Kim is actually still alive---and bore his son.

What follows is a sequence of scenes and events that had me annoyed and quietly raging in my seat the whole time---right up to the tragic ending that was wholly nonsensical. I had to ask myself... does MISS SAIGON basically exists now as simply an antiquated record of old-school Western attitudes of the past that is preserved as a product of and a reflection of its time? Or is the show a perpetuation of misguided notions that no longer need to be seen in its original, unaltered state?

Revisiting MISS SAIGON now in a more "woke" world just reminds us that the musical---however opulent and well-sung and well-acted it is---still plays into the image of Asians as immovably somewhere between exotic and primitive.

The ending, for me, is (and remains) a slap in the face for Asians feeling inferior to the wants and conveniences of the Western World. The authors, I feel, want you to believe that Kim in the end was making the ultimate self-sacrifice: giving her child the "best possible" future. Was her decision motivated by her not wanting to deal with the ramifications of her choice or was it a convenient way to expunge the Western guilt felt by Chris and his new wife, creating a cleaned-up scenario that won't have to bother the American couple moving forward as they raise this child?

That loud scream of anguish at the end bellowed by Chris? Yeah, I don't buy the motivation behind it for a second. For me that always felt empty and self-serving and yet another example of the white-washing of another culture's story. Let's face it: Kim was an inconvenience and so she must be eliminated. So the writers made it happen, because they can.

I know, I know. Many musicals---everything from WEST SIDE STORY to THE BOOK OF MORMON---have problematic inferences regarding people of color, too. But more than likely, you'll still see MISS SAIGON if you're already a fan because, perhaps, your takeaway from the show is different from those who find the show deeply hurtful to their culture and to the true history of what happened during those volatile years of fighting.

I suppose it's not a total loss... if you strip away the uncomfortable moments, you're left with extraordinary musical performances, stunningly presented. For some that's enough. For others, it's just too hard to swallow.

----

Photos from the National Tour of MISS SAIGON by Matthew Murphy.

Performances of MISS SAIGON at Segerstrom Center for the Arts continue through Sunday, October 13, 2019. Tickets can be purchased online at www.SCFTA.org, by phone at 714-556-2787 or in person at the SCFTA box office (open daily at 10 am). Segerstrom Center for the Arts is located at 600 Town Center Drive in Costa Mesa. For tickets or more information, visit SCFTA.org

Reader Reviews

Videos