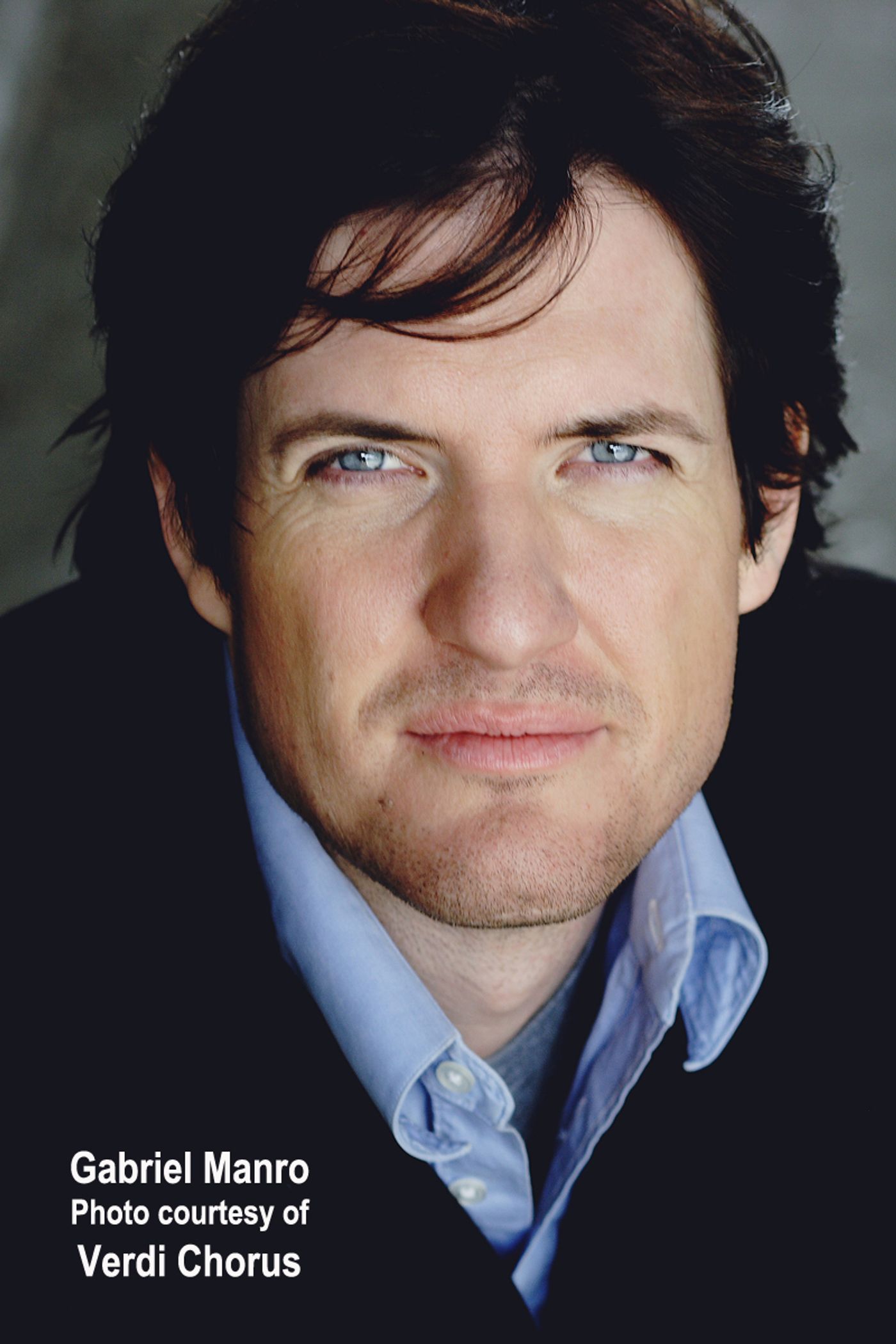

Interview: Baritone Gabriel Manro Bridging the Slim Divide Between Opera & Musical Theatre

Southern California's Verdi Chorus will cap off their 35th anniversary season with their Fall 2018 concert PASSIONE! OPERA! The two performances at the First United Methodist Church in Santa Monica on November 10 and 11 will feature four guest artists: soprano Julie Makerov, mezzo soprano Janelle DeStefano, tenor Todd Wilander and baritone Gabriel Manro. I had the chance to quiz two-time Grammy Award-winning baritone Gabriel Manro on his love for singing, the technical aspects of singing opera vs. musical theatre and his recent onstage proposal.

Thank you for making time for this interview, Gabriel!

How did you come to join creative forces with Verdi Chorus?

I was recently attending a concert given by the extraordinary metropolitan opera tenor Todd Wilander, who I have sung with many times in opera productions in Europe and New York. When visiting him backstage, he introduced me to Anne Marie Ketchum, Music Director and Founding Artistic Director of the Verdi Chorus. This put me on her radar. I'm very grateful that she found a place for me on her program for the upcoming concert.

Do you know what you will be performing already?

Yes! I, along with the Verdi Chorus and three other fabulous soloists Julie Makerov, Janelle DeStefano and Todd Wilander, will sing opera highlights from some of the grandest operas in the repertoire, including Don Carlo, Mefistofele, and The Tales of Hoffmann.

When did you realize you wanted to make singing your career?

In high school, I was selected for the California All-State Honor Choir and found myself performing great choral works like Stravinsky's Symphony of Psalms with full orchestra. It was an experience I'll never forget. At this same time, there was a dramatic shift taking place in the musical theater world toward a much more operatic form and style, with works like PHANTOM OF THE OPERA and LES MISERABLES. My formal training as a violinist and choral singer had given me a somewhat classically-bent musical taste which found a welcome home in the likes of these musical spectacles of the 80s. I knew at that time that I wanted to sing on the musical stage.

Verdi Chorus' Founding Artistic Director Anne Marie Ketchum strives to mentor young aspiring opera singers. Who were you early idols and mentors?

My idols in my formative high school years were Michael Ball (Marius: Original Cast LES MIZ, Alex Dillingham: Original Cast ASPECTS OF LOVE, etc.) and Mandy Patinkin (George: SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE). My step-brother and I would regularly travel to Los Angeles or San Francisco to see the touring casts of these musicals, and Mandy Patinkin on his Dress Casual album tour. As my musical tastes expanded in college, I began getting more into opera and my greatest mentor became my voice teacher, the legendary Elisabeth Parham. She was a great believer in me and her certainty has been an inspiration throughout my life and career. She also had a superior understanding of vocal technique which resulted in a myriad of her students becoming well-known opera and music theater singers. Ed Dixon was one of these. Another of Parham's students became a huge idol and mentor of mine, baritone David Pittman-Jennings who made recordings of the most eclectic music imaginable, from Wagner's Flying Dutchman to Schoenberg's Ode to Napoleon (Grammy-nominated Boulez recording).

Is it more challenging, or less challenging for you to perform as yourself, as opposed to as a scripted character?

These are an equal challenge. Whether performing as myself or as a character, there is a story in the text to be communicated. As I sing mainly opera or musical theater, I often have a scripted character. For instance, in the upcoming Verdi Chorus concert, I will incorporate as much as possible the overall story of the opera through the single excerpt that I'll be singing. This communication of the story through music becomes even more crucial when singing languages in which much of the audience is not fluent. My body, my inflection of tone, my musical choices etc. become that much more crucial to the communication of the story.

You sing quite a few of your roles in Italian. Are you very fluent in Italian?

You sing quite a few of your roles in Italian. Are you very fluent in Italian?

I've worked in Italy and have been quite proficient in conversing in Italian professionally and socially. I do get pretty rusty when I haven't been back for a while, but I know the meaning of every word that I sing in Italian. I approach it in the same way as I do when taking on a role in English and run across a word in the script that I don't know: I look it up and practice using the word until I'm fluent with it. It's the same in doing a role in another language--there's just a lot more words to look up!

You have been singing in a number of musical theatre productions. Do you have to adapt your singing technique performing musical theatre vs opera? Or do you have to exercise completely different vocal muscles?

It's very similar for me. The crucially functioning muscles of the voice are exactly the same. When you hear a great musical theater singer, there is a very fine coordination of the voice that is also present when you hear a great opera singer. The big difference is that the opera singer generally uses much more of their body as a resonator to amplify the sound. This is not totally necessary for musical theater as the microphone amplification is already doing this for the singer. There are all different degrees of this now with "popera" singers like Bocelli, who is a great example of someone who uses the most divine, perfect fine-muscle coordination of his voice, while at the same time not fully using his body to amplify the sound. And I don't think that this is a detriment at all. In fact, I am reminded of when I sang with Patti LuPone on The Ghosts of Versailles (Grammy: Best Opera Recording 2017). There were many world-class opera singers in that cast, but I consider her just about the best singer on the recording, not just because she is a supreme singing actress, but because of her wonderful vocal technique. So, to answer your question, the vocal muscles that I use are the same in musical theater as they are in opera. The only difference is that, in opera, I open-up and use the rest of my body in order to amplify my voice. But, really, it's so very similar and these things are only minute differences.

In opera, is one's type of vocal range usually a prerequisite of being cast in particular roles? There's no leeway to change the vocal range and orchestrations of what's already written for a hero (traditionally tenor) or a villain (customarily baritone), right? Or am I mistaken?

Yes, you are correct that vocal range is a factor. However, vocal color is also a critical factor in determining voice type and, therefore, which roles a singer will be cast in opera--yes. The lover is most often a tenor, and the baritone is, oh so often, the evil character. It's interesting to consider that body type has contributed to this paradigm. Generally tenors tend to be a little shorter and rounder and baritones/basses tend to be tall, lean, and angular. These physical features, which do very often coincide with vocal characteristics, fit into the theater archetypes set down through time immemorial and which play out in modern theater. I was just at a final callback for OLIVER!, and the other guy who was called back for Bill Sikes looked exactly like me. He was about 6'-4" with dark hair, sharp features and a deep voice. He looked just like everybody at my Javert callback twenty years ago. Opera tends to be very rigid in how a character should sound, while musicals are a little more fluid in this area. But, quite to the contrary, musicals are rigid in regards to physical type while opera cares much less about the way one looks.

Your second assumption that there's no leeway to change vocal range and orchestrations is not altogether correct. Actually, it is true of both musical theater and opera that ranges and orchestrations are rarely changed due to monetary restrictions. That is, of course, unless either the opera or musical theater piece is currently being written and work-shopped with the composer himself present. And believe it or not, there are just as many new operas being premiered as there are musicals. When I am in an original cast of a new opera or musical, I have often asked the composer to change the key of the music. However, my requests are based more on the dramatic expectations of the script than the comfort of the vocal range itself. For instance, if I'm reaching some kind of dramatic climax in a scene, I generally want the vocal line to sit a little higher to achieve the effect that the text requires. In contrast, if I'm supposed to be singing tenderly to a lover, I don't want it so high that it sounds like I'm screaming in her face. This fluidity of range has been available to the original casts of operas since opera began--Mozart, Verdi, Wagner etc. all wrote for specific singers just like Benj Pasek and Justin Paul do today. For SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE, Sondheim originally wrote the character of George for a baritone. But upon casting Mandy Patinkin in the role, transposed it into a tenor range. But after the original cast has performed these roles, the ranges are rarely changed except in certain limited circumstances. The most common case for a change of vocal range in opera is that a very famous tenor is doing a role--but he's getting a little older and can't sing quite as high as he once did--so his big aria is lowered by a half or whole-step. Very interestingly, in the Verdi Chorus concert, I am singing an aria called "Scintille Diamant (Sparkling Diamond)" from The Tales of Hoffmann where my character essentially has a "Gollum moment," worshiping a ring that gives me power over female affections. The aria is widely available in multiple keys because so many singers have had trouble with the range. Offenbach's original score sends his character, Dapertutto, singing all the way up to a G#, which is about as high as the musical bari-tenor sings. Having sung many bari-tenor roles in musical theater myself, this is not a problem. I will sing it in the original key at the concert. However, this is rare for a singer to do in most fully-staged performances because much of the rest of the opera sits much lower and is often cast with a bass-baritone singer. So, this is an example where, the demands on the bass-baritone have so often been beyond the capabilities of singers that transposed orchestrations of the aria became widely available. Instances of transposition in musical theater are quite rare as the music is written in a narrower range that can suit most male voices. Hence the name "bari-tenor"--an all encompassing male voice type. The range of the bari-tenor is achieved by not making the range too high nor too low for most male singers.

You're making me think of a couple musicals. OKLAHOMA!'s Curly and LI'L ABNER's Abner could be a baritone or a tenor, do you agree?

Yes, the range of both Curly and Li'l Abner have been written in the bari-tenor range and so can be sung by both voice types. And in musical theater, there is no limitation on vocal timbre like there is in opera. Opera-goers tend to find it a little unsatisfying to hear a baritone role being sung by someone who sounds like a tenor, or a bass role being sung by someone who just sounds like a baritone. However, I have rarely heard anyone complain about the opposite. Someone singing a tenor role who sounds like a baritone, is often enjoyed by the opera going audience.

As one with very recent experience proposing onstage in front of an audience (to Justine Prado), what did you think of Glen Weiss' proposal during the Emmy ceremonies?

I loved Glen Weiss' proposal! My favorite part was the complete unexpectedness on the part of his girlfriend, Jan Svendsen.

We had just finished the opening day of OKLAHOMA! with two performances at three-and-a-half-hours each with an hour in-between, Justine was the stage manager/assistant director. Needless to say, she was so focused on opening this show, that I completely caught her off-guard when I proposed to her at the curtain call! The fifty-piece orchestra punctuated the affair with "People Will Say We're In Love." It was just such a joy to see Justine's reaction!

Any operatic baritone roles you'd still love to tackle?

Renato in Verdi's Un ballo in maschera. Every other baritone that I've talked to about this agree that this opera has the best baritone aria Verdi ever wrote.

How about musical theatre leads?

I'd definitely love to sing the Phantom on Broadway. That and Javert. My first two favorite musicals! Ha! Some things never change!

Thank you again, Gabriel! I look forward to hearing you at PASSIONE! OPERA!

For ticket availability for the two performances November 10 & 11, 2018; log onto www.verdichorus.org

Videos