BWW Exclusive: Johnny Ramey Reflects on BIPOC in the Arts Community

As BroadwayWorld previously reported, our team is committed to to being a substantial part of a collective industry-wide effort to help address racism and white supremacy in the theatre in as many ways as possible; including a number of specific steps of action that we are already at work to implement.

If you are a Black artist or an artist of color and would like to share your stories, your work, and your experiences, or to recommend someone else that we should get in touch with for one of our initiatives, please feel free to email us at contact@broadwayworld.com.

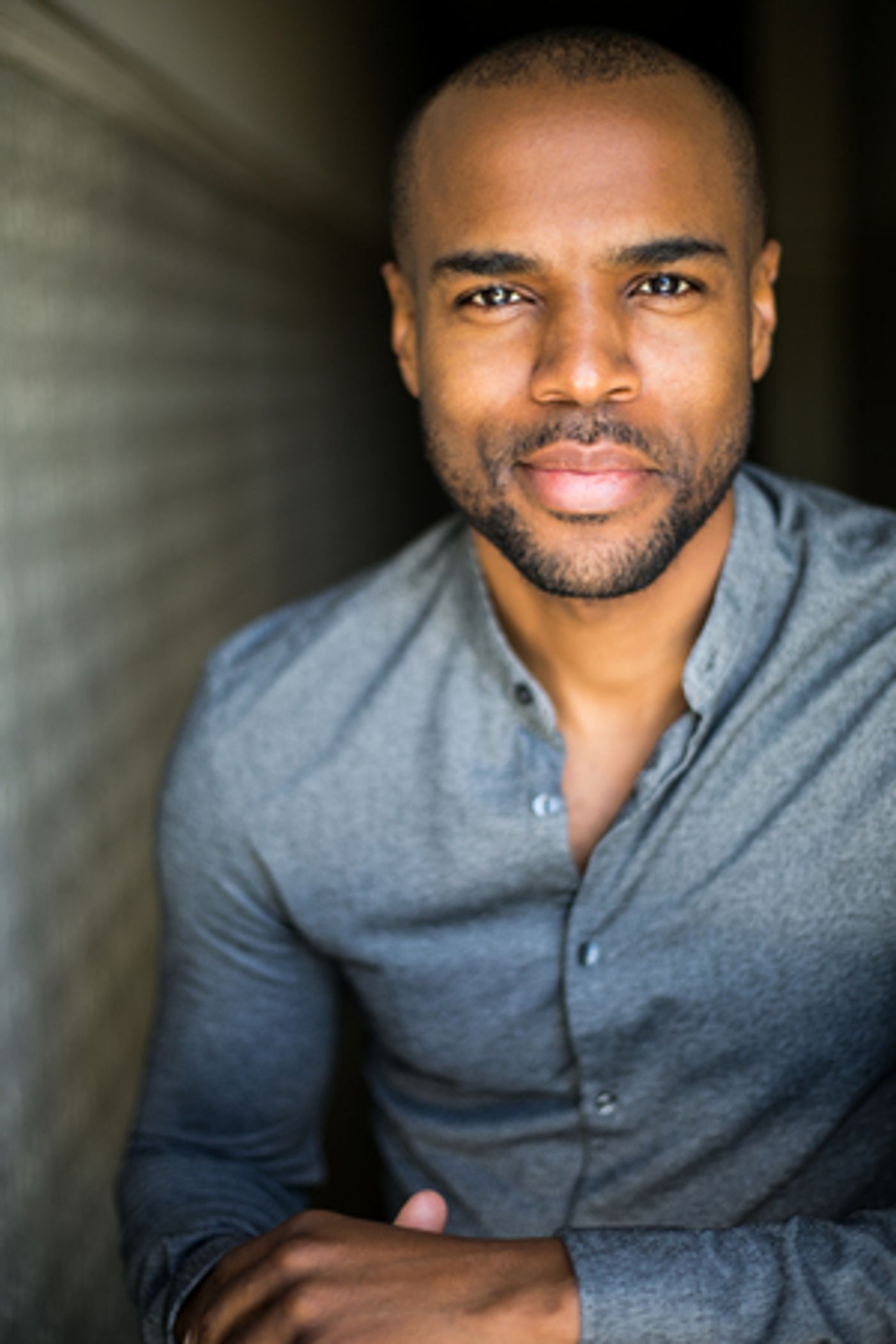

Below, read a piece from actor and Juilliard graduate Johnny Ramey, who hopes to give light to being Black & Brown within our liberal artistic community. Johnny writes:

High school was my first brush with being told that I didn't fit the ideal image for American theater as an African American kid enamored with our craft. I went on to graduate from The Juilliard School in NYC, studied Psychology, and minored in Theater & African American studies at a university pre-Juilliard career. Yet still, all the training, studying, tv/film/theater shows I've had the joy of working on throughout the years have not washed away the stench of being told from my high school theater teacher: "I would've given you the role, but... no...". Wildly enough, the pattern persisted through Juilliard, and into my professional life.

My first memory of being on stage was at my fathers church during the winter holidays. At six years old, I played Pontius Pilot for our Nativity scene. I did not know then, but a freedom within storytelling was lit. At 7, I chased after the role of Pandora's Husband for a D.A.R.E (Drug Abuse Resistance Education) production of PANDORAS' BOX. Mainly because my grade school crush, Tysherrie, would be playing Pandora. After my D.A.R.E debut, the term "Burn Out" was attributed to me, because I gave my all playing Pandora's Husband that afternoon. You should have witnessed me convincing Tysherrie, not to open that damn box.

I took a well-deserved sabbatical to soak in my 7 year-old black boy acting glory. I became a hermit- only coming out of my shell in high school, because California state deemed it necessary for children to receive state regulated exercise.

My dear mother gave me the choice of Physical Education, Band, or Theater Movement, which consisted of juggling, fight choreography, fencing, dance, and theater games. I quickly signed up for theater movement, because P.E. & Band seemed like too much sweat equity.

I fell in love with the theater that first semester. The stage, the ghost lights, the dusty fresnel lights we hung for shop class, the empty 2000 seat auditorium, the crimson velvet curtains, the catwalks... and I fell for my sole theater teacher's charisma. I saw a grown man, my high school theater teacher, weeping while reciting Shakespeare's KING LEAR. He, who could build a set, and put on BBQ fundraisers for our yearly trips to the Oregon Shakespeare Theater in Ashland, Oregon- he was magic to me.

My high school teacher was also my first brush with liberal color bias within theater. Realizing color-blind casting was not color-blind, because that act erases who I was as a Black person in society, and forced me to form in the image of those that littered popular theater, e.g. white actors, and playwrights. I could not pinpoint, in our high school theater program at that age, why it felt wrong then, but I knew it didn't feel safe at 14 years old.

Look- I fell head first into theater my freshman year. I signed up for all the acting classes, and theater shop classes, and movement classes that I could possibly get my hands on. I joined theater productions after school, where I became the lead lighting designer at 15, and was told by my white theater teacher, "In all of my years of teaching, I've never seen lighting designs as great as yours." Was he gaslighting me as a mentor, or being genuine? Who knows.

Naturally, I un-retired my acting jersey, that collected dust for close to a decade, and auditioned for David Bottrells' DEARLY DEPARTED, where I received the role of the grandfather that died in the first minute of the show. Then after my death scene, I ran up and controlled the lighting board, in full costume. The next show I auditioned for, my Junior year, was Neil Simons' BRIGHTON BEACH MEMOIRS, for which I was offered the role of a Bar Patron, who said slick words to the women and teenage girls in the bar.

A pattern was starting to form in and out of scene study class, that kept me subjugated to roles that perpetrated my theater teacher's whims of not letting me grow expressively. My mother noticed immediately and had a sit down meeting with my theater teacher to discuss how I could excel within his program as a young Black boy. I was oblivious to this fact. I was simply falling in love with theater.

Then Christopher Durangs' THE MARRIAGE OF BETTE AND BOO came down the pike and I worked my butt off for that audition. I checked my boxes: I was prepared, off book, got help auditioning, and I got initiated into the prestigious Flyer's Club in our theater program, which was akin to retiring your jersey in sports. I was then awarded the moniker of The Duke, modeled after John Wayne, with much pomp and circumstance- which now is suspect in it's glory.

THE MARRIAGE OF BETTE AND BOO was my first brush with true liberal color bias in theater. My teacher saying: "I would've given you the lead role.... but, no." It was offered to someone who barely showed up for class, fit the supposed image of the lead, and didn't want the role. I was told by my teacher, I loved, that he was going to offer the lead role to me, but he slept on that choice, and chose to go with someone who has the opposite "look" of me.

I ended up receiving the role of the father, who inaudibly mumbled his way through the show. The show after that was Shakespeares' TAMING OF THE SHREW, where that same teacher decided to give me a small role, and turn it into a "ghetto criminal", all under the guise of, "Johnny, just have fun with it."

This was not the first, nor last time I'd be passed over for a role in shows that I could excel at, or only pinned for roles that fit the mundane ideal of what a black man in our society is. While at the acclaimed Juilliard School in NYC, similar instances happened as well. Teachers with biases, especially 2nd year, hindered many a brown and black actors throughout the years. This continues in conservatories, theaters, & school class settings globally today- including Juilliard.

What has bothered me, and now I'm learning to let go, was the suppression by my teacher I thought I could trust within the liberal circles of art. The roadblocks, be it conscious or unconscious, of me excelling in our craft I loved happened early in my life. If it happened for me at 14, I can only surmise the magnitude of what happens to other Brown & Black boys and girls at such a fragile age of growth within the artistic community.

I reflect on my past, and work towards a peace. See it for what it was, and make a point to not forget, and not let the past determine my future.

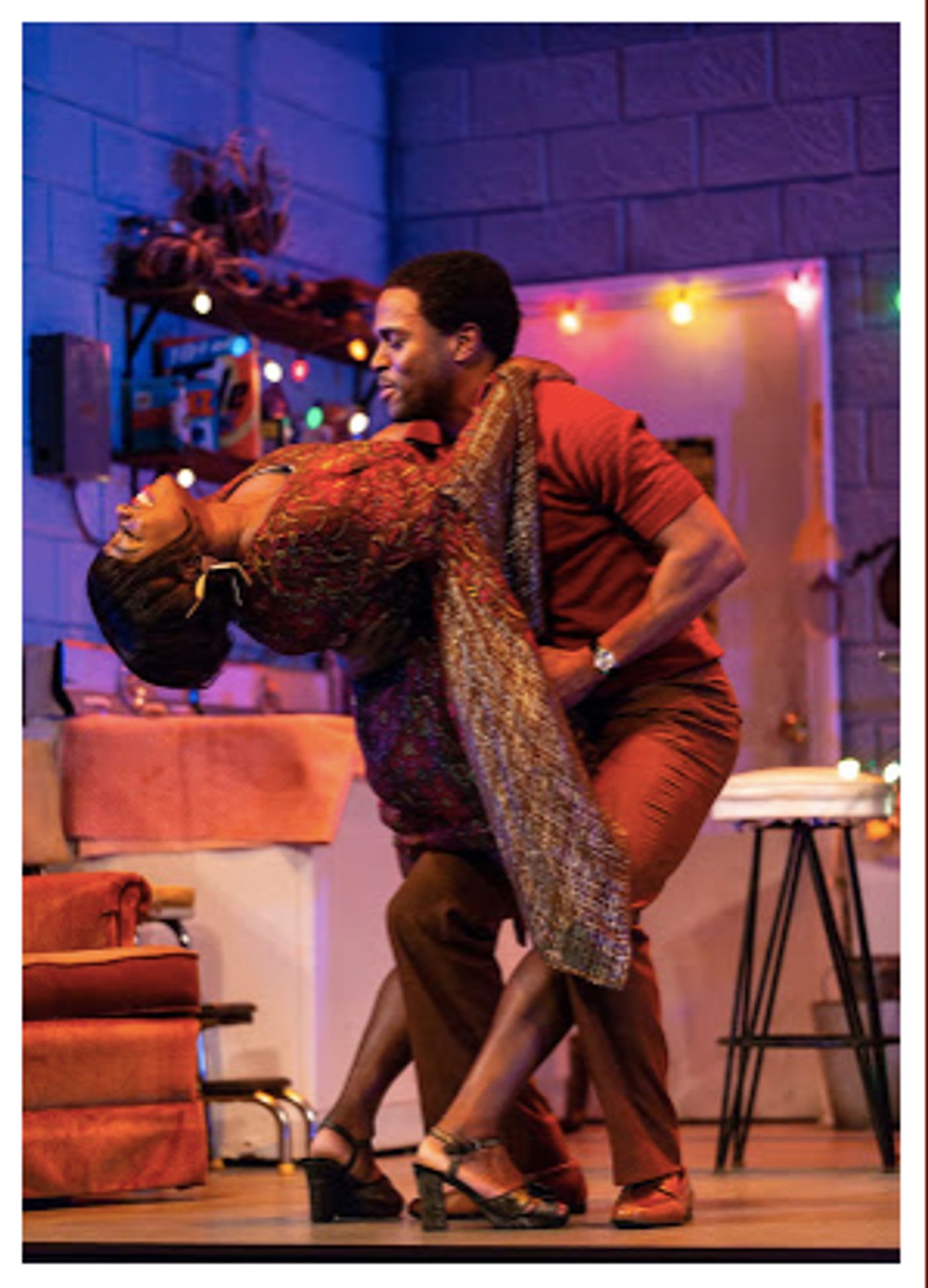

Johnny Ramey, born in California, trained, and excelled at The Juilliard School in New York. He has had the fortune to be apart of several great productions as an acclaimed actor, producer, writer and director. Johnny won the Irene Diamond Excellence in Acting Award, the Helen Hayes Award, and several of his performances awarded him Broadway World nominations. Also, several of his Directing & Producing credits gained laurels with prestigious festivals nationwide, and internationally. You can find the actor, Johnny, in several films & TV shows on streaming services.

Helen Hayes , Robert Prosky Award Winner.

Irene Diamond Award

Juilliard Graduate

Videos