Feature: MOBY DICK'S GONE MISSING at The Abbey Theater Of Dublin

Irish Forrest Gump has a whale of a tale when the Hollywood Circus came to his town.

Irish playwright Sean Cooney was six or seven years old when the Hollywood Circus came to his hometown of Youghal, County Cork, Ireland.

Legendary director John Huston served as the ringmaster and actor Gregory Peck was the lion tamer for a troupe of performers that took over Cooney’s town for the shooting of the 1956 epic MOBY DICK.

“I was only a youngster, but I remember sitting on my brother’s shoulders and watching them making MOBY DICK and looking at Gregory Peck,” Cooney said wistfully.

“Youghal was a fishing town. When these Hollywood types came in here, the local fishermen were pissed off. They were always talking about how someone should steal that (freaking) whale.”

The memories of that time of Cooney’s life left such a mark on him that he wrote the play, MOBY DICK’S GONE MISSING based on the experience. Original Productions Theatre (OPT) and the Abbey Theater of Dublin will co-present the world premiere of MOBY DICK’S GONE MISSING, in Columbus Oct. 5-8 and 12-15 at the Abbey Theater of Dublin (5600 Post Road in Dublin).

Director Joe Bishara, who previously directed the world premiere of Cooney’s A YANKEE GOES HOME last winter, said Cooney’s freewheeling storytelling attracted him to the work.

“When I first read ‘MOBY DICK’S GONE MISSING, I felt like it had the same feel and comedic timing as my favorite Joe Orton play LOOT,” said Bishara, who will direct the play as well as play Captain Ahab. “This is a break-neck comedy that will make audiences laugh out loud at a fictional account of what took place amongst the locals, actors, and the film crew.”

The cast of the play includes Sean Taylor (Skipper), Colleen Creghan (Kitty), Allison Leonard (Jonah), Scott Douglas Wilson (Gardy Gonkers), Rachel Scherrer (Birdie), Ryan Heitkamp (Olivier Scully) and Charles Easley (Queequeg).

Part of Herman Melville’s novel was set in New Bedford, Conn., but Huston thought the town looked too modern for a movie location. He didn’t encounter such problems when he shot part of the film in Youghal.

“Our town was like living in the Dark Ages until they came around,” Cooney said with a laugh.

Part of the movie’s folklore is that three models of the titular whale were lost in storms off Youghal’s coast. In cinematographer Oswald Morris’ autobiography, “Huston, We Have a Problem,” the crew created only one whale, a 75-foot, 12-ton whale that broke free from its tow line and was lost in the fog.

The whale’s appearance after that was a series of constructed tails, fins, and humps around the boat.

In Cooney’s play, disgruntled fishermen decide to swipe the movie’s chief prop and hold it for ransom.

“The play is based on their treasonous talk, you know?” Cooney said. “They’re all filled with this rage like they’re some sort of freedom fighters in planning this thing.

“They’d be telling these stories, and John Huston would walk in. They’d all shut up and go to the snug.”

The snug, Cooney explains, is designed like a Catholic confessional, only with the option of being able to order a beer or a shot. The snug originally was designed to allow women to drink away from the prying eyes of men at the public houses. They would go in these cubby holes, tap on a wooden door in the snug and a bartender would serve them their drinks secretly.

When Cooney shares a story, it rarely goes in a straight line. It meanders here, takes a short turn there, and winds its way through the countryside.

Cooney said that when he was growing up, the Christian brothers at his schools spent more time discouraging him from writing than educating him.

“My school was a horrible place for most of us because the nuns and the brothers were always trying to drive the creativity out of us,” he said. He paused for dramatic effect and then added. “I remember looking at these jetliners flying overhead. The (teachers) said stop looking out the windows at those planes going to America. You will never be on one of them. You’re stuck here forever.’ Isn't that awful?”

Cooney’s writing gift didn’t come from the Blarney Stone, a legendary rock in Ireland that allegedly gives the gift of gab to those that kiss it. He attributes his storytelling ability to his family, a youth spent working in bars and public houses as well as mental institutions, and surrounding himself with a palette of colorful characters.

“My father used to tell stories all the time,” Cooney said. “He would break into one (at the public house the family owned) and he would have the young and old all listening.”

In Youghal, Cooney would spend his evenings working in his family’s public house and the mornings working at a mental hospital. Cooney jokes that in Ireland, mental health is not a crisis; it’s a growth industry. A national study by Aware revealed that in a survey of Irish residents, 60 percent experienced bouts of depression and 80 percent suffered from anxiety.

“When you left school, you either worked at a bar, on a farm, or in a mental hospital,” he said. “Did you know Ireland has the highest rate of mental illness in all of Europe?

“When I came in, most of the patients had been given their meds by the time I arrived. I was 17 and in a white lab coat and every afternoon, they’d be telling their stories. A lot of my stories came from these mental patients.”

Cooney has been around bars most of his life. When his brothers moved to the United States, they began creating pubs in New York City. Cooney said actor Brian Dennehy served drinks and worked as a bouncer at one of the watering holes before making it big and author Frank McCourt, author of Angela’s Ashes, would hold court at the bar.

Another pub Cooney worked at had a theater built above it where patrons could see a show for $10. It wasn’t uncommon to see John Belushi, Harold Ramis, Gilda Radner and Bill Murray doing improvised shows before achieving their Saturday Night Live stardom.

Cooney said he got himself into trouble for feeding the lot and slipping them a drink every once in a while.

“The boss said to me, ‘Those guys are actors in this theater; they’re not supposed to be eating the food and drinking the drinks. I can’t keep you here if you keep that up,’” Cooney recalled. “I asked him, what are going to do on their break? He said, ‘they can bring a sandwich from home.

“I liked Belushi a lot. He’d do these impersonations of Mayor (Richard) Daley since he was from Chicago. I called him up once and there was all this noise behind him. He goes, ‘Hey Sean, I can’t talk with you right now. I am at a party with the Rolling Stones.’”

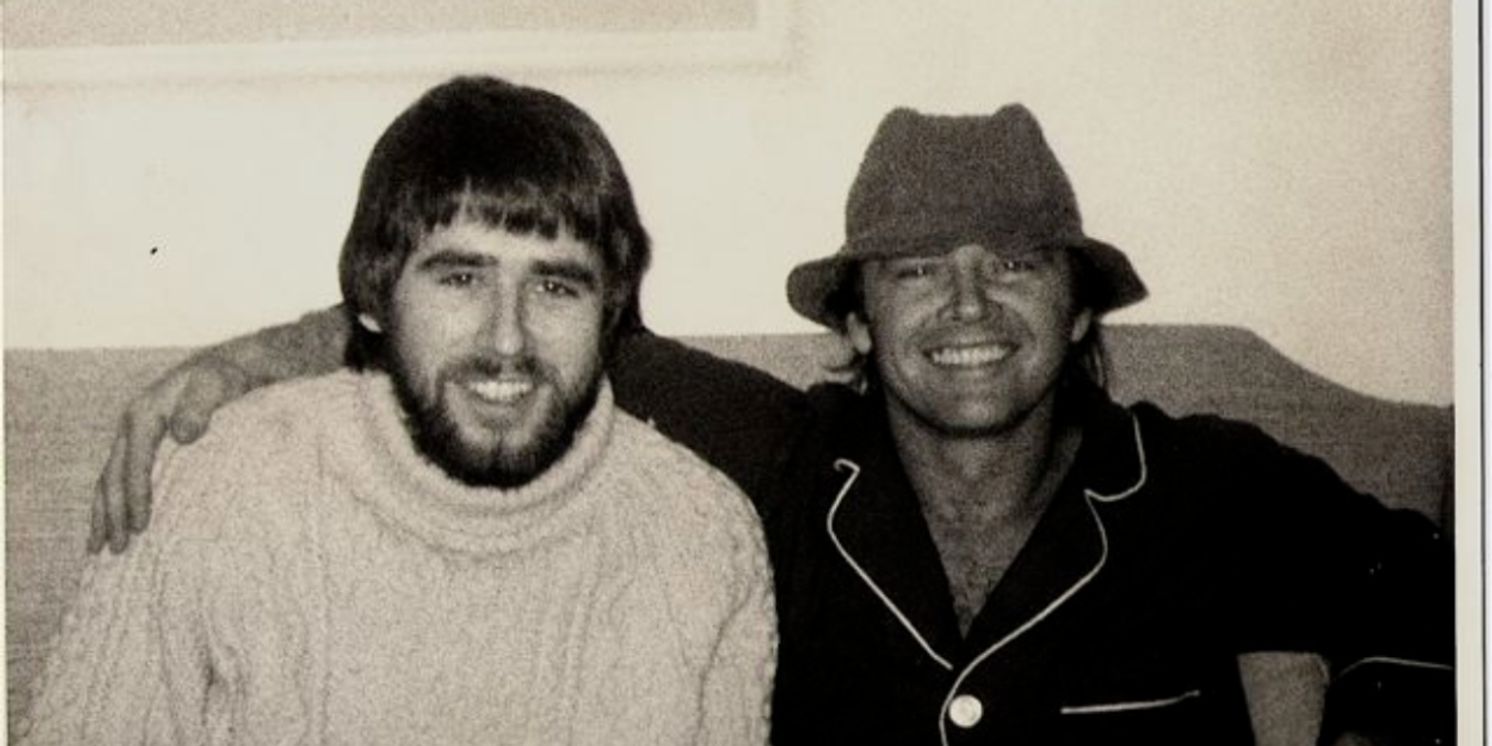

Cooney’s not above name dropping when he weaves his tales. He’s like Irish Forrest Gump, whose regaling tales of visits with Prince Juan Carlos and his wife Sophia, author Truman Capote, newsman Edward Newman, and actor Jack Nicholson. He talks about meeting Jaqueline Kennedy and her daughter Caroline, and Woody Allen in Central Park. Just when you think he’s pulling your leg, he produces a picture with one of the celebrities.

Cooney said author Arthur Miller encouraged him to turn some of these stories into plays.

“Arthur was down to earth. There was no bullshit with him,” Cooney said. “Miller knew me for 40 years and he says, ‘I've been reading a few of your plays, Sean. (When you’re not writing), what do you do with yourself?’ I said, ‘I'm between relationships.’ He said, ‘What kind?’ I said, ‘Dysfunctional women.’ He laughed and said, ‘Tell me about it. The worst five years of my life was when I was with Marilyn Monroe.’

“I was at a party with him when people like Dustin Hoffman and John Malkovich were in DEATH OF A SALESMAN. Nobody would talk with me, but Arthur then would introduce me to everybody, ‘This is my friend from Ireland and he’s a good writer.’ That was the only time they’d talk with me.”

Perhaps they were afraid they might end up in one of his plays.

PHOTO CREDIT: SEAN COONEY

Videos