Review: SHUKSHIN'S STORIES shows Hong Kong a different definition of masculinity for the Hong Kong Arts Festival at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts

Never would I have expected that the 46th Hong Kong Arts Festival opens its theatre programme with such a strong candidate from Russia.

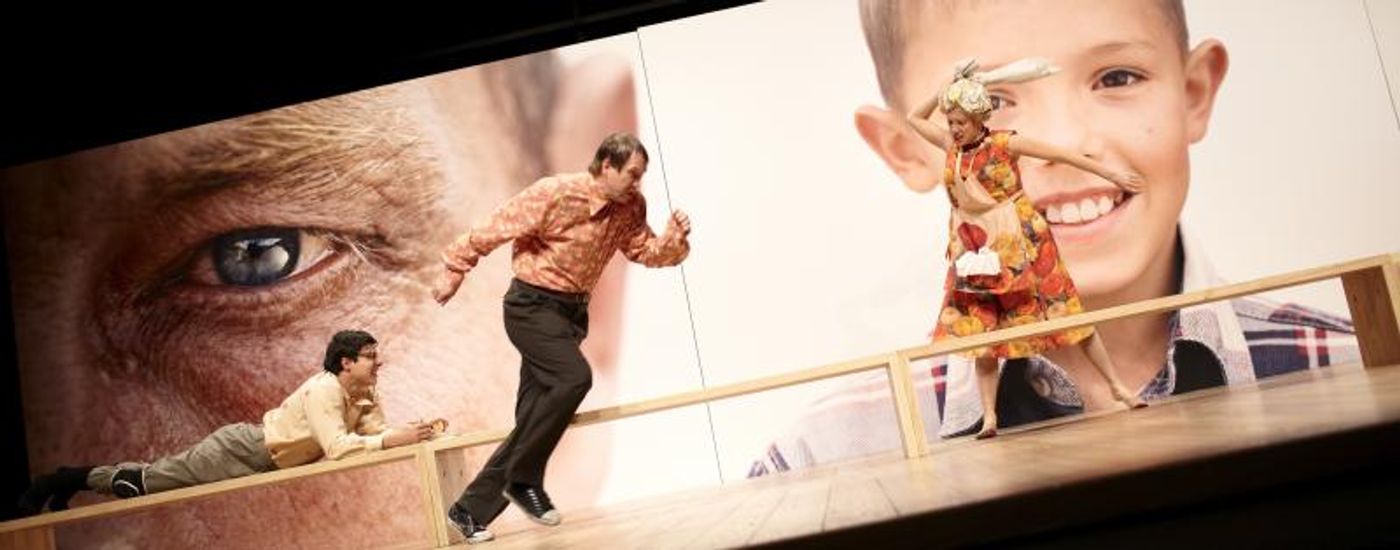

Theatre of Nations (Russia)'s SHUKSHIN'S STORIES is a three-hour 'epic' of theatre that does not look epic at all. With a simple design of a wooden platform, wooden benches, and ordinary backdrop changes, SHUKSHIN'S STORIES delivers eight short stories by Russian writer Vasily Shukshin.

One might think that this production does not manifest any speciality in spectacles as well as storytelling. You might think that director Alvis Hermanis only dramatises the eight short stories in a predictable fashion.

It is hard to grasp the decision of why it is these eight shorts stories for this particular production to celebrate the works of Shukshin, and why these stories have to be dramatised. I, however, think that from 'Stepan in Love', presented in a comedy fashion without masking the lucid interactions between Stepan and his father, to 'Microscope' which still has the comedic dynamics between husband and wife but with a much heavier ending, I start to know why it is these stories that have to be told. Before the interval, I am already in tears.

I have not read any of the stories by Shukshin before seeing this production, but from what Mr Hermanis and dramaturg Roman Dolzhansky have chosen for the play, I have to say that they are all about male figures under the context of Russian culture, especially one under the Soviet Union days.

When we think about stereotypical male figures, we think of masculinity, men who are physically strong, intelligent, and dominating. What SHUKSHIN'S STORIES provides seems like a presentation of anti-masculinity: Stepan in 'Stepan in Love' is afraid of winning Tanya's heart; Sergei in 'Boots' makes a terrible mistake of buying a pair of expensive boots for his wife; and similarly, Andrey in 'Microscope' lies to his ferocious wife of receiving a microscope as a reward due to his excellence at work.

None of these three stories at the beginning shows the intelligence of the male protagonist. In fact, they show the men's illogical senses of acting upon something that obviously will lead to negative consequences. Even though 'Stepan in Love' has a happy ending, it does not imply that Stepan's actions are intelligent. In fact, in front of Vaska, the arrogant man who considers himself as Tanya's fiancé, Stepan loses. Stepan does not win over anything but instead saved by Tanya who finally agrees to marry Stepan.

Up to this point, one might think SHUKSHIN'S STORIES is a piece that exudes anti-masculinity ideology, especially when these male figures are represented in a comical way, making the audience to laugh at them. If so, one just overlooks the fact that even in these three stories at the beginning of the show, we see inner conflicts among these men when they need to decide and act upon.

Stepan recluses himself to confrontations when he is facing Vaska; Sergei knows that the pair of boots is expensive, and also considers the possibility that his wife will not be able to fit them, but he still buys it at the end because he wants to make his wife happy with a surprise; while Andrey deceives his wife to get a microscope because he dreams to become a scientist, as well as to make his son become one as well since his passion and ability is there.

All these male protagonists are, unlike the stereotypical male image of anti-emotion, very passionate about their lives, and thus when they need to make decisions to fulfil their passions, they think and act in a conflictual way.

If what is said on stage is mostly Shukshin's own words in his stories, then Shukshin actually knows the 'weakness', and also strength, of men (at least Russian men), which is their lucid consideration in making a decision by not frankly proposing them in front of their loved ones.

Which comes to the story before the interval of the show, 'Ignaty's Arrival'. This segment suddenly changes the tone from comedy to deep emotional drama. Ignaty comes back to town and visits his family for the first time in five years. We see pleasant interactions among the family members as if it is directly from a Chekhov play or an Ozu film. We learn about Ignaty's grief of being the inferior child of his father, his envy/jealousy to his elder brother of being appreciated as 'the good son', and his deprecation of himself as a son who has not done enough to be the best for his father, yet he also wants to give more to the father he respects.

All these were presented under the mask of a family's picnic by the river, and while the women (Ignaty's mother, wife and sister) are united, singing as one harmony, we see Ignaty silently sobbing aside to repress his forever grievance, trying not to confront his father or brother with all these questions he has about his relationship with his family. In return, Ignaty's father and brother also stay silence. Are they thinking the same thing?

It is this segment that I feel deep emotions from the characters while the stage exudes a very light drama, something that collects in-depth substances of feelings, that as my father's son, I absolutely connect to this piece. It signifies the error of what we see as a man shaped by society's standards.

Ignaty is not someone like Stepan or Andrey who somehow can be considered as 'losers' by the society. Ignaty is a successful man who has his own career and family. However, Ignaty and the other three protagonists of the other three stories share a common thread. Not only the stories these characters speak are all about family relationships, but the characters also reveal their vulnerability of being reasonable yet also sensitive.

From there, we enter the second half of the show, which the tone again shifts from domestic vignettes to stories that are more epic and tragic. 'Fingerless' shows the audience a grotesque situation when the protagonist who is also called Sergei falls in love with a woman who everyone hates. Even though the ending is kind of satisfying, Sergei still thinks that the love he invests to his girlfriend is something worth treasured.

'Oh, A Wife Saw Her Husband Off to Paris' examines a tragedy, in which Kolya finds himself being trapped in a family situation. After being discharged from the army, Kolya quickly sees Valya, whom he gets to know through letters during his occupation, and marries her. Years go by, and now, with a wife and daughter, a family to support, Kolya starts to miss his carefree life back in his home village. This leads to his own ill-fated end.

'Cutting Them Down to Size' is one rare exceptional piece about questioning the relationship between intellectuals and statuses. Gleb Kapustin is a fearful figure in the country who is well-read. He keeps his dignity as a countryman and uses a rather disrespectful way to protect his fellow villagers being smeared by an intellectual, especially one who is originally from the very village.

The three stories mentioned above are about the relationships between father and son, that between husband and wife no more. They are more about the role of a man in a society, and whether individualism defines what a man should be?

Sergei in 'Fingerless' acts according to his own passion. When he loves, he loves insanely, but when he realises that he is betrayed, he can be as insane as when he is in love. In other words, he is actually sane. Sergei's passion is under his own control, and in any other situation, Sergei tries to reason his feelings. In the end, Sergei knows he still loves his ex-girlfriend, only that moral and dignity comes first.

This kind of conflict between reason (assessment of social norms) and passion of a man holds along the whole second half of the show. Kolya tries to resist his own passion for his family, and never tries to flee from his entangled situation until he realises that his passion is at the end of its life. Gleb's situation is even more obvious. As a well-read person, Gleb uses his intelligence and logic to protect his and the villagers' dignity and pride as countrymen.

Of course, one can see the unreasonable nature of these three protagonists, as one might think that these characters do not think of others instead of just themselves. However, I think the reason why these male characters act like that is that, deep down, they have something worth fighting for, no matter it is love, dream or dignity. It is only that they are also bound by social norms, especially when they are caught in a Russian society where being men has an expected image.

Because of that, these three characters act in a quite radical way to repress their own desires.

Only Stepan in 'Stiopka' does not reasons to his passion. In the last story, Stepan is a prisoner serving his years. He comes back to his home, telling his family that he has been released earlier than the due date. Everyone is happy, and they sing and dance at night to celebrate Stepan's release (one plays the accordion for the celebration). Little do they know that Stepan lies about the early release. He actually breaks out from prison and tries to see his family as early as possible.

Up to this point, we see Stepan's 'foolishness' of breaking out from prison when he actually will be released in a very short time. The officer at the end who captures him says that he has not seen anyone who is as stupid as Stepan. If only he had waited, he could have been free forever. Now he will need to serve for several more years.

However, if we question about the role of a man from the last four stories, Stepan is actually the only one who owns his passion, to be a carer for his family. He loves them so much that even when it risks a longer time in prison, he still needs to see his family right away, to make sure they are alright.

I have a feeling that Mr Hermanis and Mr Dolzhansky have discovered this common thread among these four stories, not to mention all eight stories as well, on asking what does it mean to be a man. I speculate that with the last story, it answers, to be a man is to care and to love anything a man thinks it is worth to care and love, and to act accordingly with an honest fashion. This, I think, is what Mr Hermanis expects from masculinity.

This thesis cannot be delivered without the magnificent performances by the company of actors, strongly and distinctively led by Evgeny Mironov, artistic director of Theatre of Nations, with the design by Mr Hermanis and Monica Pormale. What I see is the fullest presentation of emotions in a naked fashion. With its ordinary design, the actors move in the open space with movements that are highly stylised. This juxtaposes the realness of the interactions between the actors, with strong dynamics as an ensemble, luring me to listen to their conversations more and more by being alienated.

It is the simplest stage directions, which are obviously calculated but in a non-pretentious way, that makes me catch every breath of intensity in each story. In the end, when the actors come back out, and each of them plays the accordion as an ensemble, it releases the intensity, guiding me back to theatre as a sense of ritual. One can say it is the extended mourning for Stepan in 'Stiopka', but I view it as a celebration to the men in Shukshin's stories, to remind us what does it mean to own the male gender. It is presented and wrapped in a highly tasteful way.

SHUKSHIN'S STORIES at Drama Theatre, Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts

The 46th Hong Kong Arts Festival

Closed on 25th February 2018

Reader Reviews

Videos