Review: HADESTOWN at Blumenthal Performing Arts

The Tony Award-winning Best Musical serves up a jazzy, godly nectar.

In Blumenthal Performing Arts' Encore playbill, the distance between Anaïs Mitchell, who created the music, lyrics, and script of HADESTOWN, and Rachel Chavkin, who developed and directed Mitchell's creation, is a scant three-and-a-quarter inches. Inside that space are the neatly typeset names of 42 actors, designers, and organizations who have helped bring their vision, the 2019 Tony Award winner for Best Musical, so vividly, raucously, and meaningfully to life.

You get the idea that, in crafting and concepting this marvelous retelling of the Orpheus-and-Eurydice myth, Mitchell and Chavkin became even closer than those 82+ millimeters. Together they have created a work that is slick and glitzy, yet we find primal and profound truths amid the razzle-dazzle.

Those truths can sting, particularly when we descend into the dark underworld ruled by Hades and his abducted queen, Persephone. While Mitchell and Chavkin discard the #MeToo aspect of the royals' union, reimagining them as formerly true lovers, they point up King Hades' inclinations toward greed, exploitation, oppression, and mindless acquisition, layering on prejudice and xenophobia for good measure.

So when Matthew Patrick Quinn as Hades brought down the curtain on the first act with "Why We Build the Wall," written years before The Donald took up politics, the satire bit hard enough for the MAGA morons seated in front of us to get up in a mighty huff at intermission, never to return. Yet this concept of Hades, casually linking his excesses to global warming and climate change, isn't really an absurd overreach. Why shouldn't Mitchell and Chavkin portray him as the vilest of plutocrats, when Pluto is actually Hades' most familiar alias?

And plutocracy is where we're at.

Mitchell enriches her devilish brew with a score steeped in the decadence of New Orleans jazz, repeatedly underlined by a doo-wop trio of Fates whose only moral failing is going along with the flow. These stylish female backups are ultimately more successful in getting into the impoverished Eurydice's head than Orpheus, who is preoccupied with finishing the song he believes will restore springtime to the world. Quinn's basso sleaziness is given a robber baron vibe with an infectiously chugging railroad line running directly to his realm, and the combination of Rachel Hauck's scenery and Michael Krauss's costumes makes our dystopian world seem nearly as nocturnal as the netherworld.

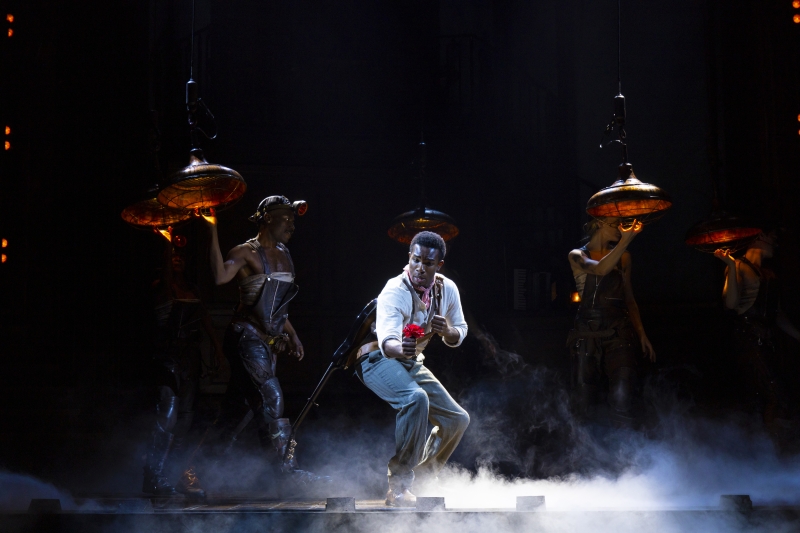

Presiding over the action and gleefully shattering the fourth wall again and again, Nathan Lee Graham as Hermes keeps us from forgetting - graceful and gliding charmer that he is - the artifice and theatricality of all we see. At the same time, he is frequently seconding the ethereal voice of Chibueze Ihuoma as Orpheus, asserting the power of music in changing our world by envisioning a better one, reminding us how music and language intertwine in the ancient ritual of storytelling.

Singing has always been key in preserving our world and our heritage. Musical narrative, after all, isn't a recent discovery championed by Verdi, Jerome Kern, Rodgers & Hammerstein, and Lin-Manuel Miranda. It dates back to King David's psalter, anonymous campfire bards, Orpheus' legendary lyre, and the Homeric Hymns, where the story of Hades and Persephone was originally told. By design, three of the pivotal songs Orpheus sings are grouped as a series of epics.

Potentially, as we find here, songs have magic. Consequence. "The Wedding Song," a beguiling duet early in Act 1 where Orpheus responds to a sequence of challenges from Eurydice, is as memorable as Hades' sardonic affirmation of walls. "Epic I" from Orpheus, the embryonic song he is working on, is enough to establish his magical power and win Eurydice's belief in him. Doesn't last when Hades comes personally calling with his saucy come-hither, "Hey, Little Songbird."

But Orpheus is able to march into hell for a heavenly cause (a recurring theme in world literature and religion, it would seem) when he melts Hades' heart with his completed "Epic III" after intermission, transporting the steely King back to his tender courting days and reconciling him with Persephone. It's here that the Fates get into Hades' head as effectively as they had gotten into Eurydice's earlier, so that the King of the Underworld attaches one pesky condition that prevents Eurydice's release into Orpheus' care from being unconditional.

Ihuoma's naivete and spontaneity turn the moment when he succumbs to sudden heartbreaking tragedy, beautifully staged as everything freezes into silence. The essence of that heartbreak registers so poignantly in Hannah Whitley's eyes as Eurydice, so achingly close to restoration, almost clearing the threshold of the railroad car that must now take her irrevocably down. All of Belk Theater and all of creation seem disappointed in that moment, even the lively and cynical Fates (Dominique Kempf, Belén Moyano, and Nyla Watson).

Paradoxically, when all stops for a precious few heartbeats, we may realize most keenly that the working relationship between Chavkin and choreographer David Neumann has been as close and precisely calibrated as the relationship between the director and Mitchell. Indeed, our director, composer, and choreographer are involved in perhaps the most delicious conspiracy of all in HADESTOWN, those precisely chosen beats when an unseen centerstage circle suddenly begins to revolve or abruptly halt.

Most of the players, particularly the drones who make up the Workers Chorus, are swept round and round by the wheel. Others like Hades and Orpheus walk at the precise pace that makes them seem like they're stationary as they move, floating on air. Then the wheel stops, and on they go, like clockwork. Or since the subplot of Persephone's arrangement with Hades is a mythic explanation of the cycle of the seasons, the circular motion we see is clockwork.

As fine as the Fates are in moving about the stage, sometimes while wielding musical instruments, our eyes are most intently riveted to the lithe movements - and eye-popping costumes - of Graham as Hermes and Lana Gordon as Persephone, bringer of springtime and wicked beverage. Graham and Gordon are both electrifying performers, so it's rather amazing when Quinn, after brooding quietly in the background for most of the first act, instantly proves himself their equal.

Together, they are the spice, the heady godly nectar that helps us savor the purity and fragility of the mere humans, Eurydice and Orpheus, all the more.

Photo Credit: T Charles Erickson

Reader Reviews

Videos