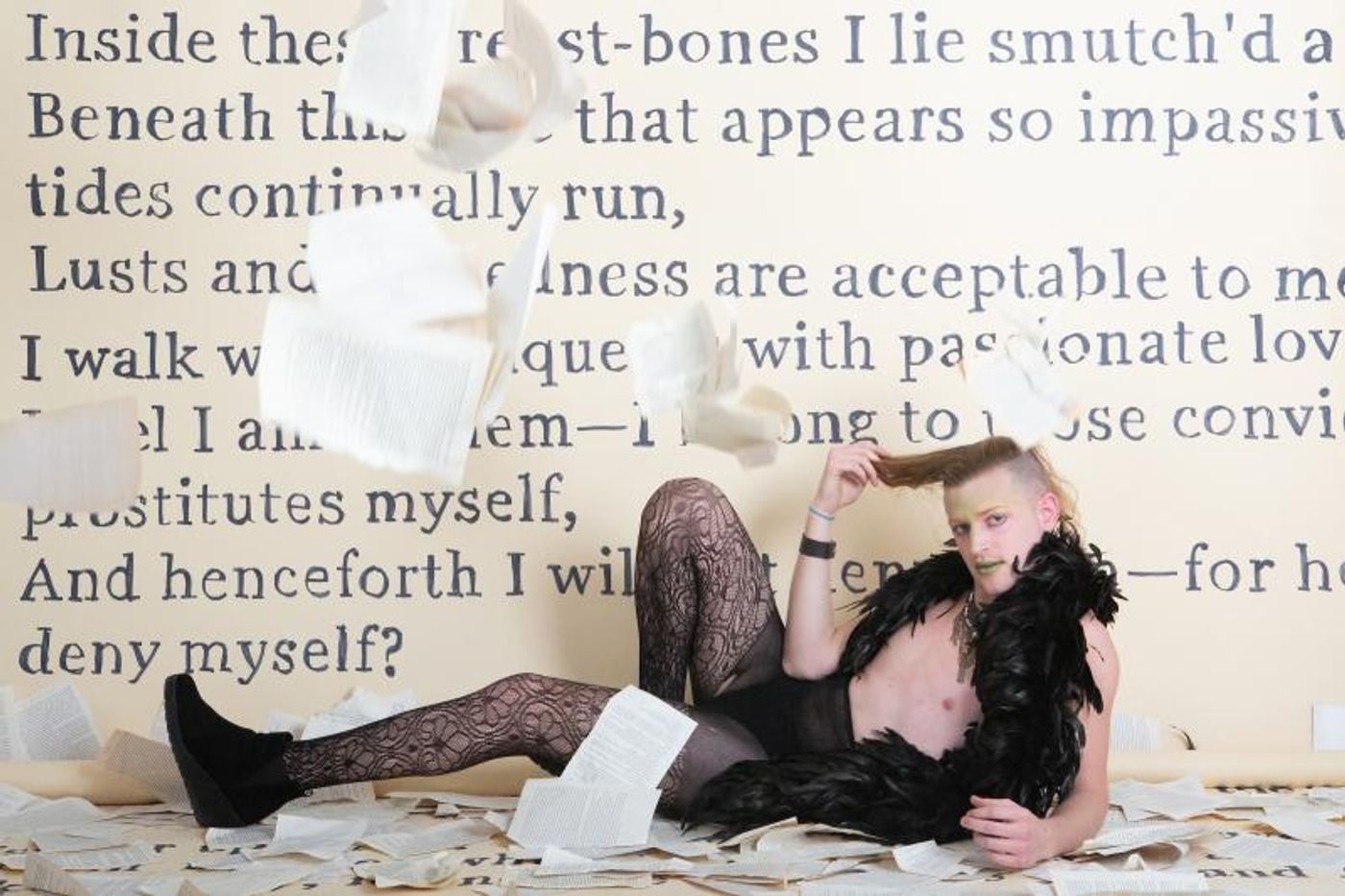

Interview: The Bearded Ladies Cabaret, a Philadelphia-Based Queer Experimental Cabaret Troupe, Takes on Walt Whitman And Other Imperfect Heroes in CONTRADICT THIS!

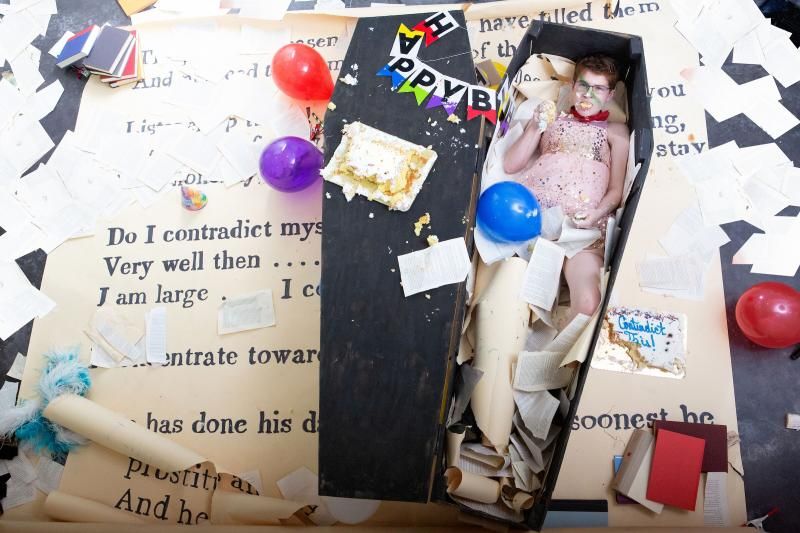

Promotional photos: Plate3 Photography

It feels in many ways poetic that both the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots and the 200th anniversary of Walt Whitman's birth fall on the same year. Late last month, we celebrated "America's greatest poet" and the legacy he left behind. Later this month, New Yorkers will take to the already-heavily rainbowed streets to memorialize the 1969 riots that initiated the LGBTQ+ rights movement. The two events form at a crossroads, one where look a little deeper into our past events and the people who shaped our future.

That's precisely where The Bearded Ladies Cabaret comes in. The Philadelphia-based experimental cabaret troupe is part of La MaMa's STONEWALL 50 celebrations, joining a group of LGBTQ+ artists from around the globe. The Beards' contribution is the New York premiere of their CONTRADICT THIS! A BIRTHDAY FUNERAL FOR HEROES, which---spoiler alert---starts as a birthday party for "much-lauded homo poet" Walt Whitman and descends into a trial, taking on Whitman's problematic political views, our imperfect heroes, and cancel culture as a whole.

CONTRADICT THIS! began as a piece commissioned by the University of Pennsylvania Libraries for Whitman at 200: Art and Democracy, a series of cultural events marking Whitman's 200th birthday. John Jarboe, the troupe's founder, says they took it upon themselves, as they always do, to ask the ever-important "why?"--- aside from it being his 200th birthday celebration, why, in 2019, are we celebrating Walt Whitman, and should we be?

The answer is not straightforward, but it is exactly the kind of question that the Beards have been interested in dissecting throughout their nine-year history, Jarboe says.

"All of our pieces are little Trojan horses... we use song and dance and story to draw you in, to make you complicit in something, and then we use that complicity to make you reflect or ask a hard question."

CONTRADICT THIS! will perform at La MaMa's Ellen Stewart Theatre from June 20-29. Directed by Jarboe, it will feature original compositions by Heath Allen, Emily Bate, Daniel de Jesús, and Pax Ressler with additional performances by the Whitman Choir and Josh Machiz. Other company members include Elah Perelman, Jackie Soro, Veronica Chapman-Smith, Sally Ollove, Rebecca Kanach, Brandi Burgess, Dan O'Neil, and Calvin Anderson, as well as a full design team including Ollove, Anderson, Reza Behjat, Jumatatu Poe, Tyler Mark Holland, Daniel Perelstein, Sara Outing, Nic Labadie-Bartz, Melody Wong, Scott McMaster, and William Boles.

Ahead of the birthday celebration/funeral/trial, we sat down with Jarboe for an interview about "performative poison cookies," queer assimilation, and reckoning with our flawed heroes.

This interview has been edited for content and length.

Tell me the when and the how and the why of how The Bearded Ladies Cabaret came to be.

We are an experimental queer cabaret company. We started nine-ish years ago (laughs) not really knowing what cabaret was about, and cabaret means a lot of different things to a lot of different people. To us, it means a kind of porous audience experience. We tend to weaponize pleasure. All of our pieces are little Trojan horses, and we use song and dance and story to draw you in, to make you complicit in something, and then we use that complicity to make you reflect or ask a hard question. We kind of, like, sit on your lap and tell you a story. And we've been doing that in Philly in small and large ways for about, as I say, nine years, performing for audiences in Philadelphia of up to 10,000 (we did that for our annual Bastille Day Festival). We've basically slept with every organization in Philadelphia and now we're looking for partners outside of the city (laughs), which is why we're dating La MaMa.

The line that I heard that I love is that you make "performative poison cookies."

We do, yeah. There's a 1930s cabaret composer, Friedrich Hollaender, who wrote the music to THE BLUE ANGEL, and in 1933, he wrote an essay about cabaret, that the cabaret is like a poison cookie that makes the "placid blood boil and inspire[s] a sluggish brain to think." We do think of our work in that way. And the idea is not that we're feeding the audience a poison cookie; we're eating it, too. We're not making self-righteous work; our work is self-reflective. And I think that's really true of CONTRADICT THIS, which is a birthday, a funeral, and a trial for Walt Whitman.

We are a queer company, and I think cabaret is a queer form because it lives in the liminal spaces between, beyond, [and] among other forms. Part of the work that the Beards do now in Philly is not just about making our own work but it's about the art of community cultivation. Our last project, which was called DO YOU WANT A COOKIE?, brought 14 cabaret artists from five different countries, and there were a couple of New York cabaret artists involved in that--- Adrienne Truscott being one of them Machine Dazzle was involved in that. We brought them to Philly and installed them in three floors of a warehouse, and so each person got their own room and the audience could wander through this kind of prismatic exploration of what cabaret is.

I feel like people don't always know what cabaret is and it's also a dirty word to some people, but... we feel like cabaret is a really radical form because it's queer, because it's porous and involves audience interaction, and it's a form that's insistent on its liveness, where, "I am not a phone. I'm literally sitting on your lap during this thing that maybe I scripted and maybe I didn't. But I will respond and we will engage in each other's humanity," and that feels, to me, very radical--- increasingly radical, nowadays.

What does your background and training look like, personally?

I'm a University of Michigan grad in Theatre and English, so it makes sense that (laughs) I'm making pieces about literary figures. And I lived in the land of mediocre Shakespeare and musical theatre for a while and then found the cabaret form. As someone who's queer and genderqueer, the form fits me better. I can talk directly to my audience, I can have a real conversation, and I feel like I can make the container. I'm not doing a prescribed container, and that feels really rich to me. I've been in Philly for the past 10, 11 years, (laughs) making weird cabaret with a bunch of misfits locally and now internationally. It feels really special to me.

Photo: Christopher Ash

Leading into the Whitman show, what are you inspired by? What draws you into a topic or an idea to make it into something larger?

Work comes from many different places. Oftentimes with the Beards, it's some combination of nostalgia, pleasure, and an un-dismissible question. With the Walt Whitman piece, we were actually given a commission from the University of Pennsylvania Library... I think our first question was, like, why? Why are we celebrating Walt Whitman right now? He's turning 200 years old, but who really was he, and is he someone that we want to celebrate? Because Whitman has a history of really problematic politics. They're overlooked by some and they're not what they teach you in school, but Whitman was a Free-Soiler, pre-Civil War, and his stance was, basically, that he wanted to protect white laborers, so he didn't want slavery to spread to the west because he was trying to protect white jobs, basically. His poetry is very nationalist and imagines an America in which the oppression of Indigenous people and people of African descent--- it's in there. His poems [are of] an imagined America.

(Laughs) That being said, he's also a queer hero. Langston Hughes touted his poetry and Allen Ginsburg, [Federico García] Lorca, Pablo Neruda. Whitman's impact is also unavoidable and he is someone who, personally, I've been very drawn to. His poetry is beautiful.

That's actually why we're drawn to this topic. It becomes less about Whitman to us than it does how do we deal with people who make us who we are and [then] break our hearts? How do we deal with a flawed ancestor? And that can be your weird, messed-up grandpa who says awful things at the Thanksgiving table, to someone like Michael Jackson, who... this documentary just came up. Can we listen to "Thriller"? Can we do the moonwalk? How do we engage with our flawed heroes?

So, that is what is at the center of this piece. Whitman, in a way, is the cookie, Whitman's birthday is the sweet entrance into it--- you think you're coming to a birthday party and, suddenly, it becomes a trial of Walt Whitman, and then a trial of Erykah Badu and Andy Warhol and Michael Jackson and Joni Mitchell and all these other people. It's really a meditation on cancel culture and flawed heroes. Right now, there's such a culture of saying, like, "You're canceled," or, "You're problematic in this way and I can't listen to you," or, "I'm muting you." So, we're really having these complicated conversations in the end about who we are and the fact that I can say that I'm not going to listen to Michael Jackson, or I can't listen to Joni Mitchell anymore because she did an album in blackface, but, actually... I spent my whole college career listening to every Joni Mitchell album. It's part of who I am. How do I respect that history and what's given to me and also acknowledge that part of what's given to me is problematic and also that I am problematic, too?

That is what is at the heart of the piece---spoiler alert---but how we deal with that is through a lot of amazing music. There are six, seven composers on the piece that are all the performers of the piece, and they've each written responses to Whitman and their problematic heroes. So, the piece is very much a quilt of this beautiful music. There's a choir and a rock band---

Yeah, I saw that--- The Whitman Choir.

Yeah, Leaves of Grass (laughs). They dress like grass. And on the stage is a huge birthday cake with massive human-sized candles. So, it is a party that goes awry.

It feels like a murder mystery!

(Laughs) A bit, yeah. The Beards... we're interested in asking questions and making a space where we can drink, party, and reflect critically on how messed up we all are.

You hit that two-part question of, "Should Walt Whitman be canceled? And can he be?" I really like the idea, especially for the Stonewall 50th anniversary, of both memorializing our ancestors and questioning them. We want to do our ancestors proud, but also did they set us on the right path to do so?

Completely. And you look at James Baldwin, and you're like, "I just can't touch that." (Laughs) That's an ancestor that's beautiful and righteous, at least so far as I know-

And don't tell me otherwise.

And don't tell me otherwise! And that is something that I hear a lot from people when I talk about the piece, is, "You can't touch that person! That's my person!" and what they're really saying is, "Oh, no, that's part of me." So, there's something about the piece- however silly and campy and joyful, I think we're accessing and exploring something that's very vulnerable for people. We just did five performances in Philly on the pier and people were leaving really struck and, I think, thinking about their CD collections a little differently and resonating with these questions. That's what the Beards try to do with our work. That's the poison cookie- there's an aftertaste, but there's a side effect. We want the piece to be still processing in your belly as you walk away.

Whitman also feels like a very natural topic to build cabaret around. He said he was "the poet of the body" and "the poet of the soul" and so centered on that idea of flesh and spirit being inseparable and that really feral kind of sexuality that lends itself really well to cabaret. This lining up with the Stonewall 50 and talking about how we balance all these contradictions, it got me thinking about the recent social media discourse that's been going about whether kink and leather and, ultimately, sex should be at Pride.

Ugh, god.

I know. It's so frustrating, especially when you consider how Stonewall and Pride was built on the backs of sex workers and the BDSM community, with Marsha Johnson and with Brenda Howard being the Mother of Pride. But it got me thinking in terms of the kind of sterile, assimilated, corporate queerness that exists right now, and then how Whitman is so revered as "America's greatest poet" but his sexuality gets detached from that. And then those of us who don't detach his sexuality have then look deeper at the nature of his politics. It's very much, where do we lie in between?

Yeah, it's so rich and complicated. And you're right--- we should be looking at Whitman to inspire us to put on our leather... he is one of those queer ancestors who is sex positive. And at the same time--- yeah, I feel you. I mean, the Philly police cars have rainbow symbols on them right now. And that also feels like that other problem of how are we respecting our ancestors. I mean, the STONEWALL movie, what was that? No one saw it, I don't think---

No! I forgot it exists until you just mentioned it (laughs).

I can never forget it exists, but I will never watch it (laughs).

Not in this lifetime. Yeah, in New York, Christopher Street and everything gets so corporatized when Pride comes around. "Pride, sponsored by Chase Bank"--- it's like, what the fuck is this?

Yeah, it's getting to the point where to be actually queer, we just have to be straight now (laughs) because they're taking--- I'll just start wearing baseball caps and using sports metaphors as a femme. I'll just start doing that and then I'll be able to be anti-assimilation.

I mean, we won "gay marriage" so everything is fixed, right?

Oh god, yeah. Painful.

Going back to the show, this is its New York premiere. In addition to the Stonewall 50th, Whitman was also nearly a lifelong New Yorker, either in Long Island or Brooklyn and, therefore, shaped by the city. Did you make any changes for the show by the road, or was it already shaped to go to New York from the get-go?

With every Beards piece, it really engages with [where it's being performed], so we're actually making a lot of changes and shifts to--- because in Philly, it was very much about his relationship to Camden. And so, we've got a whole song devoted to Brooklyn... not that Brooklyn needs a song---it's got enough already (laughs)---but we will be shifting a lot of the language to be about Whitman's relationship to New York.

In creating this show and analyzing the idea of reckoning with our flawed heroes, how do you reckon with your flawed heroes now?

Yeah, that's a really good question and something I'm still in process with. I think it's fair to say that there are different rules for different people. I cannot listen to R. Kelly at all--- never again. R. Kelly will be canceled from my life. I can still read Whitman's poetry, but if I'm going to share Whitman's poetry with someone, I'm also going to share the context of the poetry and I'm going to share some historical information about Whitman. Joni Mitchell, I can't cut out of my life completely, and I also want to acknowledge that she is in old age and saying a lot of weird stuff. That's not in defense of her--- she made an album in blackface, so I also feel like I have to take the same tactic with her, which is like, "Hey, this person's got some problematic politics and advocating for them can be harmful to people that experience oppression based on the color of their skin, or other identity factors." I'm still processing how do you do that gracefully? (Laughs) How can you share a song that you like and also be like, "Hey, here's some context for the artist"?

And maybe, for me, it's actually dismantling the idea of "hero," in general, and... trying to change the wiring so that I'm not searching for perfect people because they don't exist, and using my relationship with these amazing, fucked-up artists to say, "Okay, what am I caring for that maybe I shouldn't be caring for?" And how will my legacy exist, doing the work to examine my own inherent prejudice? I think acknowledging the problematic politics of these artists is an opportunity to acknowledge our own problematic politics and do the work. And there's just so much work to be done.

The Bearded Ladies Cabaret's CONTRADICT THIS! A BIRTHDAY FUNERAL FOR HEROES will play La MaMa's Ellen Stewart Theatre from June 20-29 as part of La MaMa's STONEWALL 50. For tickets and information, visit www.lamama.org.

Ashley Steves is BroadwayWorld's Cabaret Editor-in-Chief. You can find her on Twitter @NoThisIsAshley.

Videos