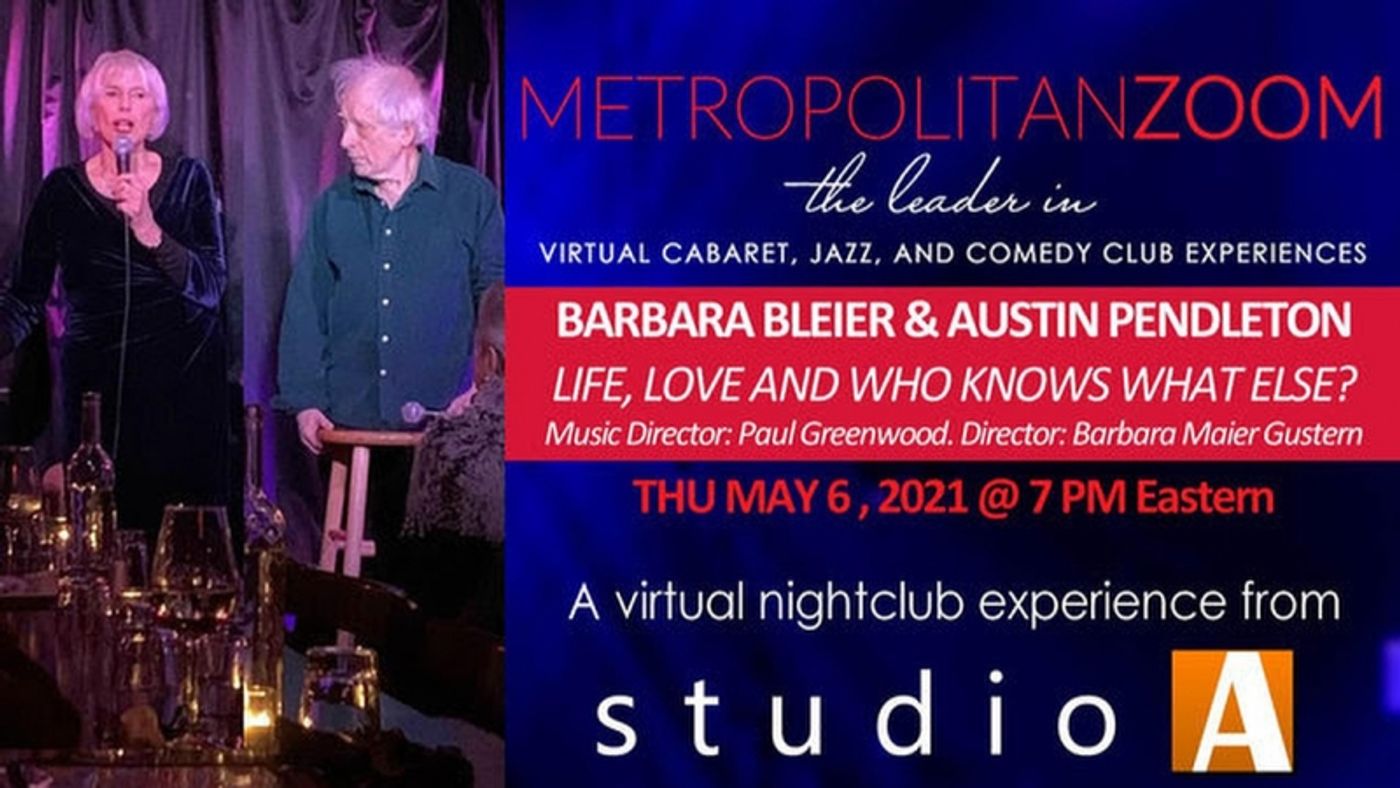

Interview: Austin Pendleton of LIFE, LOVE, AND WHO KNOWS WHAT ELSE? on MetropolitanZoom

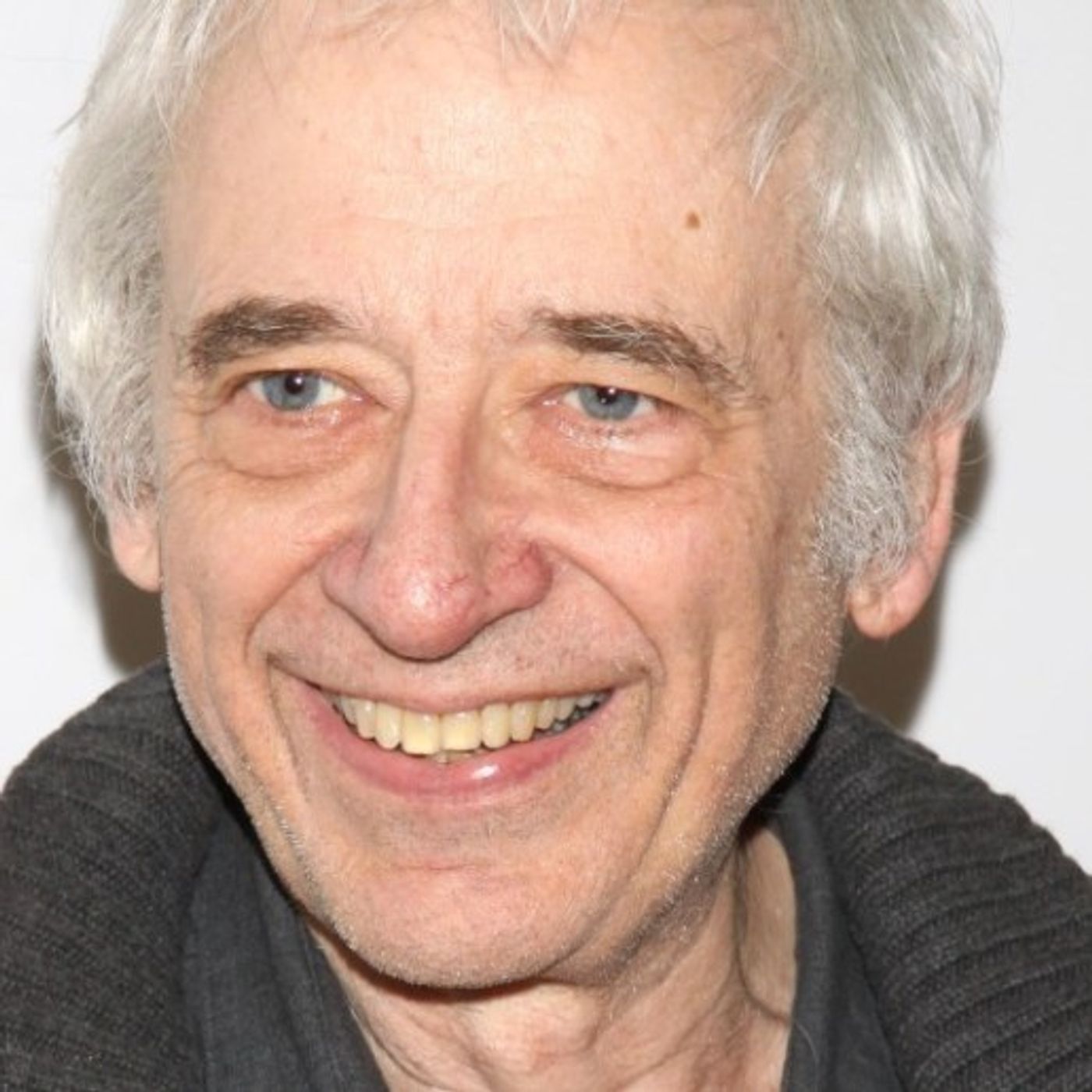

Legendary is as legendary does, and Austin Pendleton's status just keeps growing.

There's no way to hide my excitement over this interview. I won't apologize for it, and I expect everyone understands why. I mean, come on now, it's an interview with Austin Pendleton. How old was I when, as a pre-teen gay boy who was already halfway off to joining the circus, I saw "What's Up Doc?" And then came "The Front Page." There was also "The Muppet Movie" ... I mean, he was in all the great films, the ones that made me happy, all my life. Everyone has a favorite Austin Pendleton movie or five. Then, when I was old enough to seriously study the musical theater that I, so, loved, I learned he WAS Motel the Tailor. Come on, now!

There's no way to hide my excitement over this interview. I won't apologize for it, and I expect everyone understands why. I mean, come on now, it's an interview with Austin Pendleton. How old was I when, as a pre-teen gay boy who was already halfway off to joining the circus, I saw "What's Up Doc?" And then came "The Front Page." There was also "The Muppet Movie" ... I mean, he was in all the great films, the ones that made me happy, all my life. Everyone has a favorite Austin Pendleton movie or five. Then, when I was old enough to seriously study the musical theater that I, so, loved, I learned he WAS Motel the Tailor. Come on, now!

There is also the important fact that Austin was one of the first celebrity models to agree to be in my book, The Sweater Book, and his inclusion in the project led to my being able to secure many revered artists of the New York theater community that I longed to have in the publication. Most importantly, when my husband decided to leave advertising and go back to his youthful dream of acting, I told him, "Get Austin Pendleton's phone number out of my address book and find out if he's teaching right now" and since that day, Austin has mentored my spouse in his artwork (indeed, Pat calls him "Yoda Pendleton" for all the wisdom he has passed down to all his students).

So when I was asked to interview Austin and his colleague Barbara Bleier about their upcoming cabaret show on MetropolitanZoom, I waffled - was I too close to the subject? Could I do this, objectively? Then I asked myself: who better to do it? So, Broadway World readers, please enjoy this intimate chat with legendary actor, director and teacher, Austin Pendleton.

Then go to the MetropolitanZoom link HERE and reserve your tickets to see he and Barbara Bleier in LIFE, LOVE, AND WHO KNOWS WHAT ELSE? On May 6th at 7 pm EST.

This interview has been edited for space and content (but not much, cause it's too good to cut!)

Austin Pendleton, welcome to Broadway World! How was your year of Corona Crazy?

Well, it's fine. Almost entirely because of professional reasons, I was just, for YEARS, running around like a chicken with its head cut off. Then I was in The Minutes, the Tracy Letts play - we'd been in previews for two and a half weeks, and we'd finally sort of gotten it together, it really began to work. Then three days before the official opening, on the day the press was going to begin to come, the lockdown happened.

Now, if anybody had told me that I would feel a sigh of relief when that happened, I would have expected that I would be banging my head on the floor... but I had this feeling of relief - which has now gone away. I think it will probably open (it's produced by Jeffrey Richards, who's very determined to get it open) about a year from now.

So you have a job waiting for you.

Yeah. Presumably.

You always have a job. Was it hard for you having the abrupt halting of your madness?

(Laughing) Well, I would have thought it would have been - if I knew it was going to happen, I would have thought, "I'm not going to be able to handle this," because it amounts to almost an addiction. I would go anywhere to act or to direct. I wouldn't do a lot of showcases - I would do Broadway, off-Broadway, movies. The instant I heard about the lockdown (at that point it was only for a month) I breathed this happy sigh of relief. And it continues (laughing).

Have you figured out where that relief came from?

No, I don't try to figure it out. I just feel happy about it.

You've been doing a little online work recently. How are you enjoying virtual acting?

Oh, I like that a lot. And my acting classes for HB Studio are on Zoom.

Oh, you've been teaching.

Oh, yeah. One thing I was really scared about when the lockdown happened was 'Is HB Studio going to close' but we had a faculty phone call and Edith Meeks, who runs the place, said, "How about Zoom?" And I've never even heard of Zoom. So we had a three or four day training program in Zoom and started, by the end of the month, to teach our classes on Zoom, which for some reason, scene study classes really seem to work on Zoom. I keep trying to analyze why, but they really do.

So, on the subject: you have spent years crafting actors so that they can connect with live audiences, do you think that virtual theater in real time can resonate with the audience in its own way?

I don't know. I've acted in Zoom readings - I'm not sure I've ever directed a Zoom reading... no I haven't, but I've acted in a few. So, in one sentence, the foundation of HB Studio, Herbert Berghof, is that you want to connect with the audience, and the first significant step toward that is to connect with each other. And somehow it's very electric to try to reach out and connect to each other as actors on Zoom, much to my surprise. During the training program on Zoom, I thought, "Oh, this is going to be a chore," but it really was nice; I think it's because in any two character scene, the two characters are emotionally and metaphorically in different rooms. So they want to get the other person to be in the same room with them, either by arguing with them or seducing them or whatever. And on Zoom it becomes completely literal. (Laughing) That's the closest I've been able to come to try and figure out how Zoom works in a scene study class.

You really love the teaching, don't you?

Oh, I do. The fall of 2019 was my 50th anniversary year.

When you were young and starting out as an actor, did you think that you would go into teaching?

Not really, no. I had three great acting teachers when I was in my twenties. I had Uta Hagen and her husband, who began HB Studios, Herbert Berghof and Bobby Lewis. I was in the Lincoln Center Training Program from the fall of 1962 to the late spring of 1963, - there were 30 of us, and we were told on day one that at the end of those eight months (and it was eight hours a day, five days a week) half of us would be taken the company. The people... Frank Langella was in it. And Barbara Loden and Faye Dunaway, and all kinds of distinguished folks were in it. We had acting classes in the afternoon with Bobby Lewis who, among many other virtues, was a hoot. (Laughing) He was extremely demanding, but he was supportive and he was very funny and full of rich anecdotes. So Herbert and Uta and Bobby had three different approaches to the same thing, which was the Stanislavski approach to acting - the three of them, as teachers, were very distinct from each other. So I studied with Uta then, and then I studied with her after she came back from London with "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf" and Herbert just asked me to teach, out of the blue, one day. And it's sort of held my professional life together because this profession is radically up and down, it's so disorientingly up and down: you're in, then you're totally out, then you're halfway in and then you're out again but not quite so badly, but then you're way in, and then your plummeting. But teaching... I can be anxious about the business and 20 minutes into a class I'm teaching, I'm completely calm. So I think my professional life would have been a lot harder on me, if I weren't also teaching.

In fact, you are Barbara Bleier's teacher.

(Giggling) Did she say that?

She said that you've been her teacher for many years.

Yes. She's been in and out of my class a lot.

And you guys do these nightclub acts together - you've been doing your cabaret shows for a long time?

We had done one in Chicago and I think we had done one in New York about 20 years ago. And then out of the blue, six years ago, she said to me one night "Let's do a cabaret." So we did it over at Pangea and it went well, so we just kept doing them. We have Paul Greenwood, our accompanist, and we have Barbara Maier Gustern, who also sings - she has operatic training, and she herself is a singing teacher and she sings in the cabarets too. She also directs them, which is fantastic - she gives you adjustments about songs and she coaches you a little bit vocally. So it's a nice combination of people - Paul Greenwood can play anything - literally can play anything.

The show that you're doing for MetropolitanZoom is a completely new show. Isn't it?

It's largely that. In all our shows we have certain old hits we've done. (Laughing) But there are a lot of new things.

How did the four of you manage to get together to create what is relatively a new show in the middle of a pandemic?

Everybody else has been vaccinated. I'm about to be - but in all this year, I've rarely gone out of the house - so I put on a mask and walk. I live on East 76th street between Lexington and Third, and every Friday morning, we have a cabaret rehearsal at Barbara Maier Gustern's on Ninth Avenue and 28th street. I walk all the way there and all the way back; each way is an hour and 40 minutes. When we rehearse the songs, we don't wear masks - as I said, they've all been vaccinated, and they take a risk on me, I guess. (Laughing)

What do you think is the dynamic between you and Barbara that makes these shows so special that people keep coming back to see them?

Probably Barbara and I have things on all these people that are coming back. (Laughing) That's happened to me several times in acting and stuff, and I know not to analyze it because when you start to analyze it, then it gets self-conscious. We've known each other for years because she was in my class on and off for a number of years, and there was always a rapport... like the first play I was in, in New York, was a play called "Oh, Dad Poor Dad Mama's Hung You In The Closet And I'm Feeling So Sad." I was one of the three leads in it, the other two were Jo Van Fleet and Barbara Harris. Three quarters of my role was two long scenes with Barbara Harris. That had that thing you're talking about. Yes. It was directed by Jerome Robbins and he was very indecisive about casting but brilliantly decisive when he was directing; casting he couldn't make up his mind ...and he auditioned me, and he auditioned her, and he was sort of tending toward each of us. He finally called us in to audition with each other, and I think three minutes into that, he cast his vote because there was that same kind of thing that you're talking about, in a whole different key, between me and Barbara Harris. That has always been true with me and Barbara Bleier. But you dare not try to figure it out.

Probably Barbara and I have things on all these people that are coming back. (Laughing) That's happened to me several times in acting and stuff, and I know not to analyze it because when you start to analyze it, then it gets self-conscious. We've known each other for years because she was in my class on and off for a number of years, and there was always a rapport... like the first play I was in, in New York, was a play called "Oh, Dad Poor Dad Mama's Hung You In The Closet And I'm Feeling So Sad." I was one of the three leads in it, the other two were Jo Van Fleet and Barbara Harris. Three quarters of my role was two long scenes with Barbara Harris. That had that thing you're talking about. Yes. It was directed by Jerome Robbins and he was very indecisive about casting but brilliantly decisive when he was directing; casting he couldn't make up his mind ...and he auditioned me, and he auditioned her, and he was sort of tending toward each of us. He finally called us in to audition with each other, and I think three minutes into that, he cast his vote because there was that same kind of thing that you're talking about, in a whole different key, between me and Barbara Harris. That has always been true with me and Barbara Bleier. But you dare not try to figure it out.

You have very fond memories of Barbara Harris.

Oh, 100%. Yeah. She had a kind of, and I really don't use this word about actors because I think, come on, but she had a kind of genius about her. So, actually, did Jo Van Fleet - by genius I mean "very specific thing"... there's only one well you can drink that water from. They aren't a variation on somebody else, even a very brilliant variation on somebody else, which most actors are - I mean, splendid actors who are like that. The qualities of different actors overlap with each other. The other person I acted with, again for a year, in the other Jerry Robbins directed show was Zero Mostel. (Laughing) Zero would literally do anything at all on stage. Some of it would be incredibly accurate to the material... (laughing) some would have kind of a metaphorical relationship to what the scene was about... but just anything. I don't think he ever gave remotely the same performance twice, and all that was very exciting to me. And again, he had a kind of genius, a kind of a crazy genius to him. Genius is not necessarily superior; it's just that there's no one else in the world remarkably like that.

The Fiddler on the Roof experience must have been great training for you as an actor.

Oh, yeah. Also, do you know that we tried out in Detroit, then we went to Washington, but we almost closed in Detroit. Hal Prince told me that just a few years ago. The Variety out of town review of "Fiddler On The Roof" in Detroit - well, you should look it up. It's appallingly bad. I tell people about it and they look it up - it would be in the summer of 1964 and we opened in Detroit to cautious, mixed reviews that said there were problems with the show, but they were so nice and said it could get somewhere. Then the Variety review hit. And I'll never forget that day. We were rehearsing every day, performing at night, people were crying in the dressing room. My agent called me and said, "Have you heard about the Variety review?" I said, "I haven't heard about anything else, all day." And she said, "I hear they're going to fire Jerry Robbins." And I said,"Who do you go to when you fire Jerry Robbins?" (Laughing) "I think they have a problem there." Jerry just calmly took control of the whole situation, he just kept pointedly working on details all afternoon. He would adjust this. He would adjust that. He would say, "You're crossing too early. You should cross later. That'll sharpen the focus." "Take a couple of sentences out of that speech, put a couple of sentences in that speech." That kind of work. He didn't freak out, which people tend to do with a musical on the road that gets bad reviews. They go crazy and throw everything out. He said, "We know what we want to do with this show, so let's just keep refining it." Within three or four weeks after that Variety review coming out the show was just glowing. It was fascinating to watch. We opened in Washington and the whole cast hung together because we were besieged - we were a musical in big trouble on the road. And all of New York was gleefully anticipating that we were going to be a disaster. So we opened in Washington about a month after all that and got rave reviews.

I learned a lot just from that, learned a lot about acting, but I would never act the way that Zero acted. First of all, I don't have that particular kind of talent, but also I just wouldn't. On the other hand, I felt a sense of liberation from myself in working with him because you just had to stay wide open. He was going to do whatever came into his head, and that was kind of liberating to me. That part, in that play, the tailor, is the only role in my life that, on and off for decades after that, I would dream at night that I was still playing it - like every once in a while, but for years. No other part that I've played has showed up in my dreams.

Have you revisited that song in your nightclub acts?

The big song that Motel sings? No, I've never sung it in the cabaret ... well, maybe one time. But for years, I was asked to sing it at weddings. (Both laughing)

Did ya do it?

Yes. And I was decent enough not to charge money for it. (Laughing)

Well, you did tell me you'll go anywhere to perform.

Yeah, there it is... but I wasn't explicitly thinking of singing at weddings. (Both laughing)

I've noticed that you have personal relationships, colleagues, students that last for years.

Yeah.

Your artistic family is a very loyal one.

Yeah.

What advice would you give to artists about nurturing those kinds of collaborative artistic relationships?

Well, I wouldn't give any advice because you never know why it happens. There are certain relationships that completely go away - they're totally amicable, but you don't continually hang out. It's impossible for me to tell why some of them really kind of last and the others kind of slowly fade away.

I continued to be friends for years with Jo Van Fleet, and she was famously difficult; whenever there was a bridge, she burned it behind her. We fell into a thing where we would have dinner - now I would never have predicted that, but we did. And also, certainly with Barbara Harris, and Zero - maybe it's the shows that originate with Jerry Robbins (laughing) You don't ever predict it. What sometimes happens, you work with the same person again, a few years later, that kind of cements it.

Circling back around to the cabaret on MetropolitanZoom: do you have any trepidation about the virtual aspect of the show,

Yes. (Laughter from both) But then I have trepidation about everything that I do professionally, particularly acting. I get scared every time.

Still huh?

Oh god, yeah. It takes one or two forms: I get so scared before I go on for the first entrance (there was a period I went through when I would actually pray, get down on my knees and pray, to the horror of the stage manager and everybody) or just before a performance I would just get abysmally depressed, which is the anxiety turned inside out, you know? I was in a play with two other actors, the dressing rooms were downstairs in the basement, and we had to be at the top of a flight of stairs when the play opened, and when the lights went out, we'd go on stage in the dark. One night, one of those two actors said to me,at the top of the stairs, just before the show, "Well, how do you feel about tonight?" just in a comradely way. I said, "You don't want to know." He said, "Yeah! Tell me!" I said, "Right now, I feel that there is no hope of any significant life happening between any of us on stage tonight, and I have no idea how I am going to get through that. I will just be so depressed all evening that you won't be able to get anything at all from me. Are you glad you asked?" (Both laughing) Somehow the moment you get on stage and the lights come, all that converts into energy. Just like that. I always have a bumpy time before it starts.

And yet you always go back.

Yeah because I forget about that part. It's like women in childbirth - they forget how difficult it is, they have another child - actually, that's a ridiculous comparison.

It's precisely what I was thinking, and then you said it.

There are no strict laws about anything because I know actors, I worked with actors, wonderful actors, directed them, who simply don't get stage fright... and they don't seem to be in denial or anything - they just don't get stage fright.

Aren't they the lucky ones?

It's hard to say they're lucky or unlucky. It's what happens once you get on the stage that makes the whole difference. (Laughing)

You have worked, and continue to work, in every medium in show business, in every position there is. Tell me about your personal relationship with, and your devotion to, the craft of storytelling. Where does that come from?

What a good question. I grew up in Warren, Ohio, and my mother had been a professional actress before she married my father. I think one thing that had to do with it is she was living in New York - she had met my father in Cleveland, she started out at the Cleveland Playhouse, where he saw her in a play and they began to date, then they drifted apart and she moved to New York. She had just gotten a spectacular role as one of the young girls in the national tour of The Children's Hour by Lillian Hellman - not the bad one that tells the lie, but her best friend, which is a very flashy part. She'd gotten the part, and it was a huge deal, it was a wonderful credit and then just before it was going to begin, the tour was canceled because the play was banned in so many different cities - so, right out from under her. Then she met my father again in New York... so she was suddenly wide open to the feeling of "Who needs this shit?" So she married my dad, and I'm the oldest of three children - we were all born sort of around and at the end of World War Two. After World War Two, in Warren, Ohio, a group came to her wanting to start a community theater. Warren Ohio is in Trumbull County so they named the theater Trumbull New Theatre or TNT (Laughing) and the first two or three plays were rehearsed in our living room, at night, after dinner. We rearranged the furniture after dinner to conform to the set of whatever the player was, and they would rehearse for three hours in the evening. I would come down, and sometimes my brother, and hide and watch rehearsals, sometimes till 11 o'clock. The directors included my mom - she acted in a lot of shows there, but she also directed and the director would block the play and explain to the actors why they were blocking it the way that they were, how that would clarify everything in the story, EXACTLY in the way, years later, that Jerry Robbins said when he was fixing Fiddler! He would say, "The blocking's unclear here, I've got to re-block it. They shouldn't be looking at the person who's talking on this line; they should be looking at the response of the other person, even if it's in the middle of the line - cause that's telling the story." The job of the director is simply to tell the story clearly, and if the director, no matter how brilliant that director is, is not telling the story, it's all (to use the phrase of both my mother and Jerry Robbins) down the toilet. So that was drummed into me, not only when I was the child in the living room at night, but on the road with "Fiddler On The Roof". "It's all because, at certain moments, the story isn't clear," Jerry would say, "That's all that Variety review is really about," he would say. "So don't get so upset, let's fix it."

So I was weaned on storytelling and it just excited me so much how, if you staged a play the right way, you would tell the story of the play; even if the audience were watching it in a foreign language, they could kind of follow the story in little details of the staging. It all started there. When my contact with "Fiddler On The Roof" was up, I was invited out to TNT to direct my mother in "The Glass Menagerie" and Hal Prince said to me, "Are you going to renew your contract?" I said, "Well, actually I've been invited to direct my mother in The Glass Menagerie" in Warren, Ohio. He said, "Okay, I'm not going down in history as the person who got in the way of that."

(Both laughing heartily.)

And that was the start of your directing career.

Yes! That, and the fact that when I was in the Lincoln Center Training program, one day I did a scene from Hamlet that I'd been assigned by Bobby Lewis, and he said, "Don't stop being an actor at all - but there was a moment in that scene that you just did that had a directorial sense to it. You should also think about directing." After the Lincoln Center Training Program, Bobby was teaching at The Yale Drama School... and so it was Nikos Psacharopoulos who I knew because I'd been an apprentice at Williamstown, and one day Bobby offhandedly said, "I think Austin has a directorial sense." A few years later I was having my annual spring breakfast with Nikos, we would talk about the upcoming season at Williamstown, and he said, "And by the way, this time, maybe you do the directing thing." I said, "What directing thing?" (Laughing) He said, "Bobby tells me that you have a certain sense as a director, so why don't you direct a play this summer at Williamstown?" And I said ok. I never thought that "The Glass Menagerie" with my mom would be a kick off to a directing career - I just thought it would be exciting. It did go very well, I have to say.

Yes! That, and the fact that when I was in the Lincoln Center Training program, one day I did a scene from Hamlet that I'd been assigned by Bobby Lewis, and he said, "Don't stop being an actor at all - but there was a moment in that scene that you just did that had a directorial sense to it. You should also think about directing." After the Lincoln Center Training Program, Bobby was teaching at The Yale Drama School... and so it was Nikos Psacharopoulos who I knew because I'd been an apprentice at Williamstown, and one day Bobby offhandedly said, "I think Austin has a directorial sense." A few years later I was having my annual spring breakfast with Nikos, we would talk about the upcoming season at Williamstown, and he said, "And by the way, this time, maybe you do the directing thing." I said, "What directing thing?" (Laughing) He said, "Bobby tells me that you have a certain sense as a director, so why don't you direct a play this summer at Williamstown?" And I said ok. I never thought that "The Glass Menagerie" with my mom would be a kick off to a directing career - I just thought it would be exciting. It did go very well, I have to say.

So the first two shows I directed at Williamstown were "Tartuffe" and then three years later I came back and directed "Uncle Vanya" - "Uncle Vanya" was a big hit and led to a whole lot of other jobs, as a director, in other places, including Broadway. So it just sort of happened. I hadn't really ever dreamed of a directing career. THEN the next two or three shows I directed at Williamstown were flops; I've often thought if the first two had been the flops, it might've ended right there. But the first two were hits.

Well, every career has the hits and the misses, every one of them.

Yeah. But it helps if the hits come first.

(Both laughing.)

Speaking of the hits...

Yeah.

I don't think that I know a single person who doesn't say What's Up Doc? and My Cousin Vinny are their favorite movies.

I so didn't want to do My Cousin Vinny. The director was an old friend of mine. In 1967 (this is how show business works) I was in London and I was going to come back to New York and act in the Mike Nichols production of "The Little Foxes", and one Wednesday afternoon I was passing the theater where the London production of "Fiddler On The Roof" was playing. I was getting kind of lonely so I thought "I'm going to go backstage and introduce myself to whoever is playing Motel." The performance was almost over, so I went backstage and introduced myself and he said, "You must come back and have tea with me and my wife, in our flat," so of course I did. He said, "Of course, you'll see the evening show tonight," so I did, even though I hadn't come to London to see "Fiddler On The Roof", but yeah, ok. And then he - Jonathan Lynn - and his wife, Rita, and I kept that up literally all night, and talked. That was the beginning of this friendship, which continues, to this day.

He came over and started to direct in New York and then Hollywood, and his second film (I think) was My Cousin Vinny. He sent it to me and I flipped through it, I looked for my part, and when I saw that the part had a stammer, I called up Jonathan and said, "What ever made you think I would do this?" cause, as a kid - and a little bit into my early adulthood - I had a real problem with that - and he knew it. He said, "Well, you understand it," and I said, "Jonathan. No way am I doing that movie. I do, incidentally, think it's a brilliant script and the kind of material that you do better than anyone in the world, but I do not want this part. I don't want to do it, I don't want to revisit that." And he said ok. So then I came home and my wife said, "Jonathan wants to take you to dinner at the Greek restaurant around the corner." I said, "I know what this is about, no way is he going to persuade me to do this movie." Well, two bottles of whiskey later, I agreed to do it. And it was a nightmare to do because I had a real problem with it when I was a teenager, and then I worked my way through it as an actor through a lot of vocal training. You're always afraid that if you do it, it's going to start up again, even if you're doing it as an actor, it's going to release all that out again, and you're going to be stuck with it again.

So it was traumatic to make it. And I thought, "It's going to be a cult film." It's a great script. But for years I could not get another movie. Two or three years after that, I got a cluster of them, including two more with Jonathan Lynn, and with people I knew, like Barbra Streisand. I'm convinced right now that they gave me these parts because My Cousin Vinny had just put a stop to it. If I went to interview for a role in a film, the director would say, "I really loved you in My Cousin Vinny," and that would be code for "No way am I hiring you." I would get offered other movies where I would stutter and I would say, "I'm not doing it." And some of them were like "One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest," absolutely great roles, and I said, "I'm just not going to do it."

Well, you stood your ground. You were true to yourself.

Yeah. And I still do it. I remember when the play "One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest" was done while we were running "Oh Dad" and Jo Van Fleet said to me, "You should go audition for that - I don't mean because of the stutter, I think it's a brilliant role for you - don't be ridiculous, Austin." And I said, "I'm not going to, Jo" because in "Oh Dad" I had to stutter too. I was in that play for a year, and, oh my god, that was hard. If you already are a stutter, it's very dangerous to play one on stage because you never know when it's going to get out of control. It was very tense year, except I loved those two women, Jo and Barbara... oh, I was in anxiety all day, every day for a year.

One night I lost control, and that afternoon I'd been to see an Ingmar Bergman movie, and to this day I remain convinced that that did it. (Laughing) Then, from that it was up and down, up and down. I tried to pull out of the show. I told the stage manager, "I've got to pull out of the show," and it was off-Broadway, so I had a two-week out. The next day, the stage manager calls and says, "Stop at Jerry's on your way to the theater tonight," and I thought oh god. So Jerry said, "Okay, I can't keep you from leaving, but I don't want you to quit," and I said, "Why? Jerry, it's got your name on it, and some nights I'm just out of control." He said, "I believe my reputation will be secure." (Laughing). And he said, "If you quit this, you'll be afraid ever to act again. And I want you to act for the rest of your life."

It must be great to have someone like Jerry Robbins believe in you that,

Yeah. And we wouldn't be having this conversation if it weren't for that conversation. So I stuck in and I began to get a mastery of it again, then it fell apart again. Then Barry Primus - I said, "Barry, I don't know what to do," and he, literally, gave me subway directions to go down and audition for the class Uta Hagen taught. These key moments, had they not happened along the way, things would be very different.

You've had remarkable triumphs and setbacks.

(Laughing) Setbacks is a euphemistic word for some of them. (Both laughing really hard) Catastrophes!!

What has been your secret to staying grounded and grateful and continuing to move forward?

I'll tell you the turning point, and it's a story that involved Lynn Redgrave. In the late seventies, I played a season with the Brooklyn Academy of Music. I got in those three shows and I got progressively horrifying reviews. The third one was apparently particularly bad. In fact, I was talking to my agent on the phone that morning about having interviewed for a film, she suddenly broke down sobbing, and this is was a pretty hearty lady, Deborah Coleman, and I said, "What's the matter?" She said, "We can't not talk about it." I said, "What?" She said, "The New York Times." I said, "I take it it's not very good." (Laughing) "Darling. Don't read it. Do not read it under any circumstances." Then I walked out into the hallway and the woman from across the hall, who was a good friend of ours, came out and she, literally, recoiled when she saw me. (Laughing) She looked horrified. I said, "Don't worry, I've just heard about it." That afternoon - I'd been in a movie with Lynn Redgrave and I directed her in Chicago in a play for which she and the play won the Jeff Awards - there was a Shaw play and there was talk of bringing it into town with her and Irene Worth, so we had a meeting over at Circle in the Square about it. At the end of that meeting Lynn said, "You have time before you got to Brooklyn tonight, right? Let me take you to the Russian Tea Room."

So we sat down and ordered and she said, "I read the review." I said, "I hear it's pretty bad." She said, "Well, yeah, it's awful. You shouldn't read it, of course." (Now, here's another one of those conversations.) She said, "Here's what you do, Austin... If John (Gielgud) or Ralph (Richardson) got a review like this in London - and they have, as did my father (Michael Redgrave), it's always understood in London that they will be on stage again the next season. New York is not like that. New York is radically unforgiving about reviews like this. You won't be asked to do anything in what they call the mainstream for about seven years." She was correct right down to the number of years. I couldn't even get an audition. I would call up casting directors who I knew from being a director and say "Could I get an audition for this?" And they would do a tap dance. I would say, "I know the pressure you're under, but could I just get in the door?" And they would say, "Absolutely, I'll get you an audition. This is unfair, what's going on." I would come in - one time the director actually said, "What's he doing here?" Or even if that wasn't explicitly said, the temperature would drop by about 35 degrees when I walked in - it was like, over. But what Lynn said was, "What you do now, Austin, is you just go anywhere to act. Act out of town, act in showcases, act anywhere, just keep acting. So when they finally do forget about this and offer you a mainstream job, you will have been acting all that time. Because New York is ridiculous about this: it turns an actor off when they get really bad, it just flips the switch and turns them off. But that's how you should deal with this, just keep acting." And that saved my life. I just did what she said.

After that, I got on the subway and went out to Brooklyn - the play was "Waiting For Godot" - what makes things even more painful, it was a role I had triumphed in, in college, that set me on the path to being a professional actor. Now that same role was about to end my career 20 years later. (Laughing) There's a small kid in Godot, it's a very small part - I came into the dressing room we all shared, he was sobbing and Sam Waterston, who was in the play, was saying, "RJ calm down, all of us get bad reviews sometimes." "BUT WHY AUSTIN?" RJ was sobbing."How could people say such mean things about Austin?!" (Laughing) That talk with Lynn landed so much in me that about a week later I was able to turn that performance around. What I'm telling you is key conversations that occur when things are really bad and somebody like Jerry Robbins or Lynn Redgrave comes in with the right thing to say.

Austin, would you ever feel comfortable writing a book about your experiences and memories?

Oh, people are after me to do that and I could actually sit down and write it now in three weeks - open final draft and start writing. (Both laughing) Every time I do that I say, "I don't want to do that - I want to write another play!" In fact, I just started writing another play, and people say, "Well, that's lovely, and I hope it turns out really well... but will you write the fuckin' book?!"

(Laughter all around).

Barbara Bleier & Austin Pendleton LIFE, LOVE, AND WHO KNOWS WHAT ELSE? Plays on MetropolitanZoom on May 6th at 7:00 pm EST. For information and tickets visit the MetropolitanZoom website HERE.

Videos