Feature: A Time For Change and It's About Time

How my experience as an Asian American informs my life and my work.

This is a photograph of my grandfather, Celestino Blanco. He immigrated to America from the Philippines when he was thirteen years old because there was no future for him there. When he told childhood me stories about the life he had there, I understood why; how a thirteen-year-old managed to leave the Philippines and move to California, all on his own, was something he never shared, that I never asked, for the sake of his privacy. .jpg) When he arrived in America he adopted the name Benny, and though he would become an American citizen, he always had a strong connection to the Filipino community of whatever city he called home. During the years that I knew him, he and my grandmother lived in a small farming town near Fresno, California, where he could regularly be found in the company of others with the same heritage as he. I was not often exposed to his friends or his heritage, beyond the Filipino dishes he cooked when we visited in their home (his Adobo was especially good). I never learned to speak Tagalog because Benny spoke it, primarily, during his frequent outbreaks of violent temper, instilling in me fearful associations with the language. Indeed, growing up I did not feel any inclination to learn about my heritage. I simply accepted that the largest part of my DNA was Filipino.

When he arrived in America he adopted the name Benny, and though he would become an American citizen, he always had a strong connection to the Filipino community of whatever city he called home. During the years that I knew him, he and my grandmother lived in a small farming town near Fresno, California, where he could regularly be found in the company of others with the same heritage as he. I was not often exposed to his friends or his heritage, beyond the Filipino dishes he cooked when we visited in their home (his Adobo was especially good). I never learned to speak Tagalog because Benny spoke it, primarily, during his frequent outbreaks of violent temper, instilling in me fearful associations with the language. Indeed, growing up I did not feel any inclination to learn about my heritage. I simply accepted that the largest part of my DNA was Filipino.

This is a photograph of my mother, Juana Blanco Mosher. As a boy, I believed her to be the most beautiful woman in the world. I still believe that she is the most beautiful woman in the world. Growing up, I knew that my mother was not Caucasian, but I did not spend time thinking about it. She was the daughter of Benny Blanco, which I saw in her face; I was the son of Juana Mosher, which I saw in my face. It seemed perfectly natural to find these shadows of my mother and grandfather passing through the family, though not all of us - my younger brother was born with red hair and green eyes like Benny's wife, my grandmother Marjorie, who was of Scots-Irish and Cherokee derivation. Being Filipino didn't occur to me when I looked in the mirror or looked at my mother - all I saw was the most beautiful woman in the world, and that was all I needed to know.

This is a photograph of my mother, Juana Blanco Mosher. As a boy, I believed her to be the most beautiful woman in the world. I still believe that she is the most beautiful woman in the world. Growing up, I knew that my mother was not Caucasian, but I did not spend time thinking about it. She was the daughter of Benny Blanco, which I saw in her face; I was the son of Juana Mosher, which I saw in my face. It seemed perfectly natural to find these shadows of my mother and grandfather passing through the family, though not all of us - my younger brother was born with red hair and green eyes like Benny's wife, my grandmother Marjorie, who was of Scots-Irish and Cherokee derivation. Being Filipino didn't occur to me when I looked in the mirror or looked at my mother - all I saw was the most beautiful woman in the world, and that was all I needed to know.

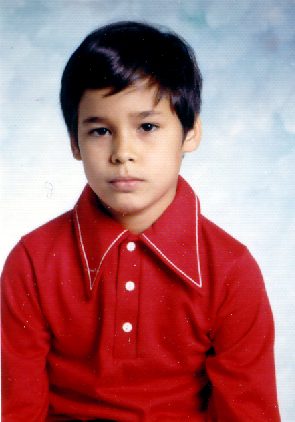

This is a photograph of me in elementary school. If I look unhappy it is because I was for much of my childhood. I entered the public school system in the autumn of 1969, and during those years my family lived in the Northern States of New Jersey and Ohio. The Vietnam War was in the news and people of Asian descent were not always welcome in all social circles. It was on the school playground that I was first called a gook. The list of epithets that I heard spoken to my childhood face was extensive and not worth the time it would take to type out. Suffice it to say, the feelings caused by all of the mean behaviors I experienced left a mark, especially when compounded by the fact that I was more effeminate than the average elementary schoolboy. I was an easy mark for bullies of all ages. Suddenly, at the age of ten, I found myself in Europe, attending schools in which the student body was made up of young people from countries all over the world, and the bullying became limited to the fact that I was, quite clearly, a homosexual schoolboy: I assumed that my racial heritage would no longer be a source of pain for me.

This is a photograph of me in elementary school. If I look unhappy it is because I was for much of my childhood. I entered the public school system in the autumn of 1969, and during those years my family lived in the Northern States of New Jersey and Ohio. The Vietnam War was in the news and people of Asian descent were not always welcome in all social circles. It was on the school playground that I was first called a gook. The list of epithets that I heard spoken to my childhood face was extensive and not worth the time it would take to type out. Suffice it to say, the feelings caused by all of the mean behaviors I experienced left a mark, especially when compounded by the fact that I was more effeminate than the average elementary schoolboy. I was an easy mark for bullies of all ages. Suddenly, at the age of ten, I found myself in Europe, attending schools in which the student body was made up of young people from countries all over the world, and the bullying became limited to the fact that I was, quite clearly, a homosexual schoolboy: I assumed that my racial heritage would no longer be a source of pain for me.

Flash forward a couple of decades, when came the advent of the digital age, an age when gay men met other gay men through online websites like Gay com, which evolved into apps, the like of which everyone in the world is now aware. It turned out that the bigotry in the gay community was prevalent in manners even worse than that from my childhood; it seemed a group of people who had, throughout history, been discriminated against was just as bigoted as the people I had encountered while growing up. Online profiles declared "No fats, no femmes, no Blacks, no Asians" and, often, people would ask me, right to my face, "What are you?" in an effort to discern whether I was Puerto Rican, Italian, Jewish, Greek... and, invariably, upon hearing "Pacific Islander" they would disappear. Even people who weren't gay men seeking an Asian-free assignation asked me about my heritage, trying to figure out where I came from. I never liked it because I am not to be defined by any one thing, not my heritage, my sexuality, or anything else. I came from my Mom and Dad. I came from Texas. I came from Switzerland. I came from a lot of variants - but those weren't the factors in peoples' minds when they asked me, "What are you".

The reason I share all of this information is so that people will understand my ongoing investment in inclusivity within the club and concert industry of New York City, and at Broadway World Cabaret. When BWW creator and CEO Robert Diamond asked me to become the head writer and editor for this page, I told him I had an interest in writing about everyone and everything, that I wanted to cover all the acts, from singers to comics, from drag to burlesque - I'd even cover magic acts and ventriloquist acts if I could find them. I wanted to write about artists of every demographic possible, whatever their age, race, skillset, identity - it was my ambition to give every artist in the business a place to share their story so that the Broadway World readers could see the magic and the majesty of the cabaret community. Once I was in place at BWW, we made a start: I would spend days out of each week reading the calendars of the clubs to see who was performing, who we could write about, and what diversity could be found. On those club calendars, I found performers who were Black and who were White, I discovered Latin singers, transgender and non-binary artists, I came upon people of all the (as the saying goes) colors of the rainbow who performed in the cabaret rooms and nightclubs of Manhattan. There was no shortage of talent in the clubs... but there was a shortage of diversity.

Where, I asked myself, were all of the Asian performers? There was a glaring dearth of artists of Asian descendent in the business - not just Asian, but also Middle Eastern extraction. It weighed on my mind in a troublesome way for which I could find no explanation, but also no manner of verbalizing. In the five months that I was at Broadway World and in the clubs seeing shows, before the lockdown, I found very few artists of Asian heritage about whom to write, in spite of my concentrated efforts. There were occasions when an Asian singer was included in a group show, like when I saw Raymond J. Lee in "Broadway Daddies" at 54 Below, and Vishal Vaidya appeared in an installment of "I Wish: The Roles That Might Have Been." Telly Leung made appearances in a couple of different clubs and Ann Harada did guest spots in group shows. I was blown away by Shani Hadjian's show at The Laurie Beechman Theatre, and the Helen Park Songwriter's night at 54 Below was out of sight. I was unhappy to miss Natasha Castillo's Eighties show, but I was lucky enough to catch Arielle Jacobs as a guest artist in Perry Ojeda's act The truth of the matter, though, was that I wasn't finding a big enough representation of Asian performers in the nightclub industry, and no answer seemed to be presenting itself to the question of why.

I thought about my friend, Daniel Park, who made it to Broadway in the 2004 revival of Pacific Overtures and, immediately thereafter, left show business. When I asked Danny why he told me that the uncertainty of work was too high - that he couldn't just wait around for productions of Pacific Overtures, The King and I, and Thoroughly Modern Millie to offer the mere possibility of work. How many other Asian actors go through, have gone through, the same thought process leading to the decision to quit the business? That's theater, where there are specific requirements for the roles being cast - I was looking at the club and concert industry, where there is no need to fit into a certain type, a specific character... all you have to do is have the wish to work and the talent to deliver. Pat Suzuki had, long, been one of my favorite singers - she had always had a strong presence in the clubs. I had to admit to myself, though, that she was the only one I knew of until Lea Salonga started performing in concert. Jose Llana has a huge presence as a concert performer in the Philippines but, to the best of my knowledge, has yet to begin performing in Manhattan clubs, something for which I have hoped for a while. I was stymied.

Then I began to ask myself: is the club industry not welcoming enough? In my experience, the answer was yes, this is a welcoming community. What could be done to assure young talents coming up through the ranks, and older talents looking for a new place to express their artistry, that there is a seat for them at the table? How is it possible to let all the artists of all the demographics know that they and their work will not only be welcomed into the community, into the industry but that the community and industry are ones that have been made with them in mind? It was a thought process worth pursuing, and one for which I was given an interesting, if slightly informative, glimpse into during the summer months of 2020.

Ari Axelrod was doing some video interviews for Broadway World with artists like Faith Prince and Christine Ebersole, and during the time when the George Floyd murder led to many discussions about racism in America, Ari and I agreed that it would be prudent to conduct a panel discussion on race relations in the industry. I reached out to a number of club artists, in order to line up a truly diverse panel, only to find that the subject of racism is one not every person of color cares to discuss, maybe not in public, maybe not all, but definitely not on camera. An invitee shared with me that they had not processed their thoughts on race relations in the industry to a point that would permit them to discuss, another told me that, as a mixed-race person, they rarely experienced any racism, while someone else offered that they simply had nothing to offer on the topic. I was able to schedule one member of the community who spoke frequently and openly about their heritage, but that person canceled at the last minute, too uncomfortable with the topic to participate. Reflecting on these encounters, I realized that I never spoke of my experience of blatant or microaggressive racism unless it was the punchline of a joke. There was a place where I had continued to hold onto those experiences and the feelings left behind, years later, there was a bigger part of the conversation taking place that, so far, did not include my personal participation. It was time for me to speak up and join the discussion.

Bigotry comes in many forms. The only people qualified to speak on the prejudice that has been experienced are those upon whom the crime has been committed. Nobody can or should presume to speak on their behalf or assume that which they have felt under the thumb of prejudice. Because of the Atlanta shootings, the discussion has started and many are stepping up to the podium to speak. Let us all ask what we can do to bring all of our family members to the conversation of prejudice versus equality, of love versus hate, of burgeoning peace. This country and the industry of show business have been working toward equality for Blacks, Gays, Women, and now the race of Asians has been, through unhappy means, brought into the conversation. Let us not forget that discrimination is everywhere. People are judged, hated, harmed because of their race, religion, gender, body, age, and more. The history of the need to end hate crimes already features Matthew Shepard, Breonna Taylor, Brandon Teena, countless women, many Jewish people, and an ongoing litany of other beautiful people of uniqueness who have been assaulted and murdered, a list that now includes these beautiful innocents of the Atlanta shootings. Each of us can contribute to the change by becoming a part of the conversation, by creating a bell in our head that goes off every time we start to speak or behave in a manner that could be deemed prejudice by the person on the receiving end of that speech or behavior. Change begins right where each of us stands, and the truth is that change doesn't take a lot of effort, only a lot of awareness, and consideration, and humanity.

As for Broadway World Cabaret, I promise that, during my tenure with this organization, I will continue to seek out diversity in the clubs and put a light on it. I encourage all multifarious actors to put together a club act when you're not in a show and bring it to the world of small venues - if there's one thing I've learned in the last nineteen months, it's that the nightclub community of New York City is ready and waiting for your artistic contribution.

And I am ready to tell your story.

Comments

Videos