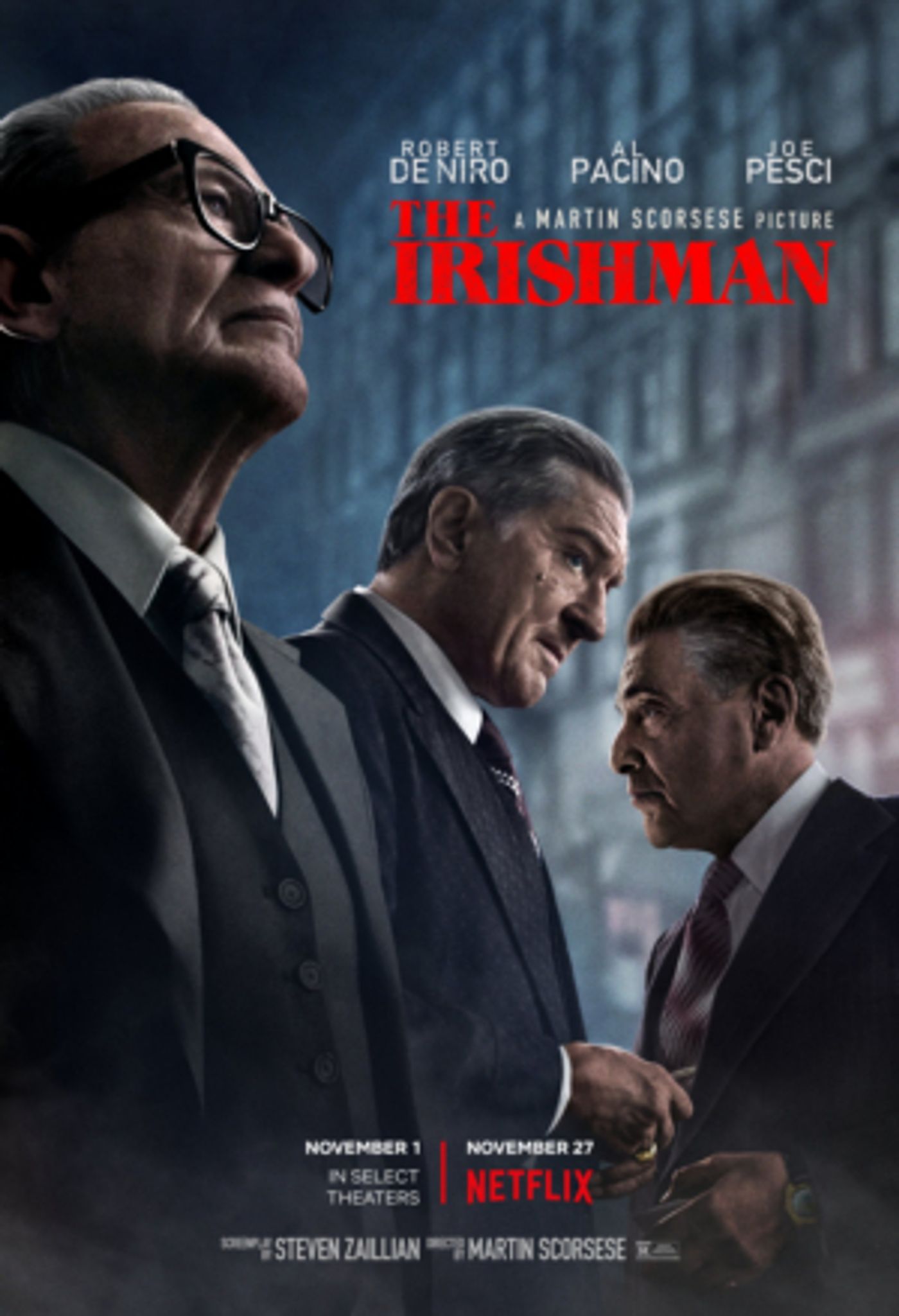

Review Roundup: What Did the Critics Think of Martin Scorsese's THE IRISHMAN?

Robert De Niro, Al Pacino and Joe Pesci star in Martin Scorsese's THE IRISHMAN, an epic saga of organized crime in post-war America told through the eyes of World War II veteran Frank Sheeran, a hustler and hitman who worked alongside some of the most notorious figures of the 20th century.

Spanning decades, the film chronicles one of the greatest unsolved mysteries in American history, the disappearance of legendary union boss Jimmy Hoffa, and offers a monumental journey through the hidden corridors of organized crime: its inner workings, rivalries and connections to mainstream politics.

The film also stars Harvey Keitel, Ray Romano, Bobby Cannavale, Anna Paquin, Stephen Graham, Stephanie Kurtzuba, Jack Huston, Kathrine Narducci, Jesse Plemons, Domenick Lombardozzi, Paul Herman, Gary Basaraba, and Marin Ireland.

Let's see what the critics are saying...

David Rooney, The Hollywood Reporter: Despite the movie's many pleasures and Scorsese's redoubtable directorial finesse, the excessive length ultimately is a weakness. Attempts to build in social context during the Kennedy and Nixon years, at times intercutting news footage from the period, aren't substantial enough to add much in terms of texture. The connections drawn between politics and organized crime feel undernourished, and the movie works best when it remains tightly focused on the three central figures of Frank, Russell and Jimmy. Netflix should be commended for providing one of our most celebrated filmmakers the resources to revisit narrative turf adjacent to some of his best movies. But the feeling remains that the material would have been better served by losing an hour or more to run at standard feature length, or bulking up on supporting-character and plot detail to flesh out a series.

Richard Lawson, Vanity Fair: The film offers a hand of comfort, not necessarily to Frank Sheeran-who is, yes, given something of a warm glow by the end, perhaps unfairly-but maybe to anyone wondering what the clamor of their life has all been about. Whether a viewer wants to accept that comfort in the form of a movie about murderers is, of course, up to them. I found myself reluctantly taken by the movie, and the way Scorsese uses it to maybe, just a little bit, atone for some of his own past blitheness about violence. In The Irishman, a merry darkness slowly becomes an elegy, ringed with guilt. And what could be more Irish than that?

Chris Nashawaty, Esquire: The Irishman isn't a masterpiece. But it doesn't miss by much. If Netflix's ambition now and going forward is to become more than just a one-size-fits-all streaming superstore and to take its place as a serious annual player at the Academy Awards, then it was a canny move to lure Scorsese with its no-questions-asked, budget-be-damned largesse. What it got in return isn't just any old mob movie or Goodfellas-lite, but rather a haunting, poignant, twilight-of-the-gods drama tinged with regret, driven by monumental ambition, and smothered in the red sauce of violence. And, in the end, what could be more American than that?

Johnny Oleksinksi, The New York Post: This has a different tone than your average gangster film. Plenty of marks are shot in the forehead, yes, and a lot of wine is poured in the corner booths of dimly lit Italian restaurants, but it's also knock-down, drag-out-into-the-river funny. The best line belongs to De Niro: "Usually three people can keep a secret," he says. "When two of them are dead." And Pacino is a ham as Hoffa, wildly gesturing like a coked-up cheerleader and bickering with everybody.

Nick Schager, The Daily Beast: Aided by ace cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto, Scorsese stages his action with a reserve that's anything but static or sluggish; his (relatively) unshowy camerawork perfectly suits a story drenched in despondency. That's also true of Robbie Robertson's soundtrack, punctuated not by Scorsese's beloved Rolling Stones but, instead, The Five Satins' "In the Still of the Night," which is all the more haunting for being so thematically apt. As evoked by an initial cut from senior-citizen Sheeran to a gun firing and blood splattering a wall, the lingering weight of violence on a person's conscience and soul, especially as they near death, is central to The Irishman, resulting in an oppressive, and devastating, elegiac atmosphere.

Bilge Ebiri, Vulture: The Irishman uses this very mortal limitation to its artistic advantage. It turns De Niro's age and slowness into an existential ethos: Scorsese's film is framed very much as the memories of an old man looking back on a life of violence and regrets - De Niro's character sits in a wheelchair in a nursing home, mostly unresponsive, in the opening scene - it makes sense that the film's version of "young" De Niro exists in this neither-here-nor-there space SOMEWHERE BETWEEN youth and old age. This mimics the way memory often works: When we remember incidents from earlier in our lives, we imagine ourselves as younger versions of the people we are now, instead of the people we really were back then. As has already been memed to death, De Niro in The Irishman carries the same glower throughout the film, whether he's a young man executing Nazis in World War II, a middle-aged man doing mob hits, or a geriatric man reflecting on his joyless, loveless, empty life. That's sort of the point of the film.

Benjamin Lee, The Guardian: And it's in this introspection where the film gets really interesting. When a director returns to a genre they're most associated with, it can often feel like a greatest hits montage. For much of its duration, The Irishman covers familiar ground but is slickly entertaining, if a little repetitive in the third hour. In the last 30 minutes, as the pace slows and the quips subside and the violence quells, we are suddenly made aware of the ultimate price of this lifestyle and of the crushing savagery of old age. It's a finale of stifling bleakness, of the pathetic emptiness of crime and of men who mistake their priorities in life, the discovery arriving all too late. There's an almost meta-maturity, as if Scorsese is also looking back on his own career, the film leaving us with A HAUNTING reminder not to glamorise violent men and the wreckage they leave behind.

Eric Kohn, IndieWire: De Niro's always at his best in the context of a Scorsese-mandated tough-guy routine, and Frank Sheeran gives the actor his most satisfying lead role in years. Sheeran appears in virtually every scene, and the story belongs to his colorful worldview the entire time. He may be an aging man telling tall tales, but that puts him in the same category as THE ONE behind the camera. Sheeran, however, lost touch with his world long before he left it. With "The Irishman," Scorsese proves he's more alive than ever.

Owen Gleiberman, Variety: Yet the film, by design, is episodic in a way that's small-screen-friendly and a little "objective." It sits back and gawks at its characters - their close-to-the-vest style, their violence, their drive for dominion - rather than drawing us into any sort of shattering communion with them. It shows us the explosive force of their actions without necessarily asking us to be deeply moved. The first two "Godfather" films added up to a kind of tragedy (almost a Hollywood version of Shakespeare), because they were about how far men could fall who had soaked their rise in blood; we watched the humanity drain out of Michael Corleone until he was a waxworks Mafia vampire. "The Irishman" never glamorizes the violence it shows us, and never risks MAKING IT look like a lark; the film presents Mob crime as the cutthroat utilitarian business it is. But what it also shows us is characters who don't necessarily feel a lot for themselves. They're clockwork operators - efficiency experts of violence. There's little on the inside for them to confront, because that part of them is already dead.

Reader Reviews

Videos