Review: The MOTHER of All Operas, by Gertrude Stein and Virgil Thomson, Staged by Juilliard at that Other Met

This Met or That Met, It was a MOTHER of a Performance from MetLiveArts

I wonder if there was fear in the hearts of anyone at the Metropolitan Museum when the decision was made to let the Juilliard staging of the Gertrude Stein-Virgil Thomson opera THE MOTHER OF US ALL use the Engelhardt Court of the American Wing, as part of the MetLiveArts series.

No, not because of the difficulties of dealing with the acoustics of the mammoth space--no small issue for singers and orchestral musicians to maneuver in--but whether the huge glass ceiling could sustain the power of soprano Felicia Moore's voice without shattering into a million pieces.

The good news--or at least part of it--was that the ceiling remained intact. The rest of the story was the success of director Louisa Proske's often-pageant-like production, using singers from Juilliard's Marcus Institute for Vocal Arts, including a notable alumna, Felicia Moore, as Susan B. Anthony.

(The amplification needed in the space was no more intrusive than that of the New York State Theatre at Lincoln Center, back in 2000, when it was staged by City Opera, though it was sometimes hard to figure out where the singers were in the space.)

Also adding to the evening's achievement was the participation of members of the New York Philharmonic, under the singular baton of Daniela Candillari, which did fine work with Thomson's varied, melodic score. The lithe choreography was by Zoe Scofield. As a whole, it was the kind of work we've come to expect from the productions spearheaded by Juilliard.

Socolof. Photo: Stephanie Berger

Director Proske called the opera "History, reinvented" in the program and clearly Stein mythical powers as a writer are in full view here in achieving that goal.

Though today's librettists sometimes have to fight for recognition, Stein was duly acknowledged as the center of the opera's success. She used the fight for women's suffrage and its most famous face, Susan B. Anthony, to weave a story blending fact and fiction. This was her second collaboration with composer/critic Virgil Thomson--the first was FOUR SAINTS IN THREE ACTS--and they certainly knew how to work together with spectacular results.

Proske's description of suffrage as "women's work, frequently uncredited, oh-so-patient, intensely collaborative...a kind of quilting across history" bears a resemblance to the librettist-composer relationship (though obviously they're not all women). But the story is more than a simple tale of "getting the vote". It intertwines the public and private lives of the characters, the real and the imagined, to fill out a storyline that refuses to be tied into the linear (thank you, Ms. Stein) but rather jumps from platform to platform, much like the story it tells.

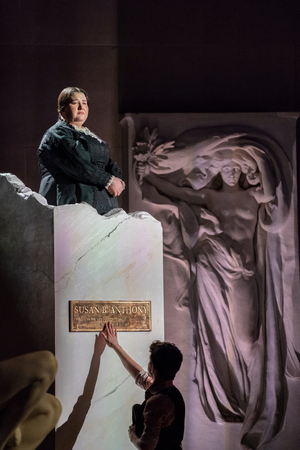

Proske's production was filled with small but meaningful directorial touches: The crushing of the ballot box to show that real opposition to suffrage remained, the poignant mounting of Anthony into a monument to her battle in a room filled with real sculpture-were riveting.

Photo: Stephanie Berger

Beth Goldenberg's costume design went far in helping the singers build their characters--a tough job when there were so many in the company. Combining the contemporary with the historical--club girls with suffragettes--she somehow made it all make sense.

Moore was spectacularly fine as Anthony, modulating her huge instrument as called for--from a whisper to nearly Wagnerian--and using her finely tuned acting skills. Her combination of intensity and strength with delicacy was remarkable. But she was hardly alone in the story. Among the standouts were the strong presence of mezzo Erin Wagner as Anthony's companion, Anne, bass-baritone William Socoloff, who was admirable as Daniel Webster, both orator and fighter with words.

Tenor Chance Jonas-O'Toole was a charming, scene-stealing Jo the Loiterer (nicely paired with mezzo Carlyle Quinn's Annie Oakley-ish Indiana Elliot). Soprano Deborah Love was an appealing Constance Fletcher, fictional lover of John Adams (nicely done by Ian Matthew Castro), while Jaylyn Simmons, another soprano, was a fluid, graceful Angel More, a fictional lover of Daniel Webster.

Though there wasn't much in the way of scenery--except for some of the exquisite art that calls the Engelhardt Court home, such as a golden Diana, with atmospheric lighting design by Barbara Samuels--the video by Kit Fitzgerald that set the scene (I loved the opening with the marching Suffragettes in particular) was highly effective, even on the busy walls of the museum.

One hundred years after the 19th Amendment prohibited the states and the federal government from denying the right to vote to citizens on the basis of sex, the issue of who gets to vote and how the law can be manipulated is far from settled. "Failure is impossible" is a thought that goes through the story of suffrage. Yet even today, the tricks of unscrupulous politicians try to disenfranchise certain voters from the rights that the Constitution promises. The battle continues.

Reader Reviews

Videos