Review: JEPHTHA, Royal Opera House

Allan Clayton's return to Covent Garden is not to be missed

300 years have passed since Jephtha, Handel’s Greek tragedy-infused oratorio, was heard at Covent Garden. Now a lustrous new production helmed by artistic director Oliver Mears begs the question: is it a lost classic? Or one to consign to the history books?

300 years have passed since Jephtha, Handel’s Greek tragedy-infused oratorio, was heard at Covent Garden. Now a lustrous new production helmed by artistic director Oliver Mears begs the question: is it a lost classic? Or one to consign to the history books?

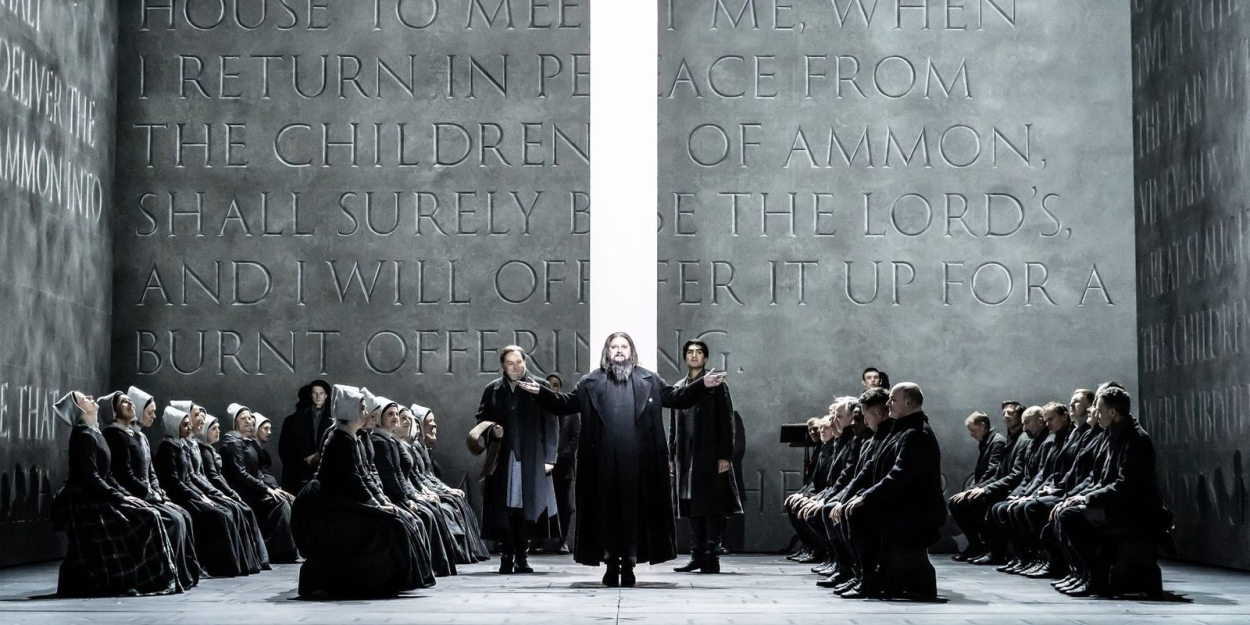

To conquer the invading Ammonites, the Israelite judge Jephtha vows to sacrifice the first thing he sees if he is victorious. Military success ensues but his celebrations are short lived when his daughter Iphis walks into his room. Jephtha is trapped, a mouse in a maze. Visually imposing slabs of rocks, inscribed with his vow, sleekly shift back and forth, continually trapping him in their metaphysical tangle. “It must be so” he repeats gloomily, the words slicing a little deeper each time.

His decision is impossible. Fate is literally set in stone: echoes of Agamemnon ring loud in the ensuing clash of the immoveable forces of religious duty and familial love.

But Mears finds a mesmerising balance between the moral maelstrom and psychological thrill. Like his recently revived Rigoletto, his directorial eye leans on the cinematic. Free flowing images bathed with angled light conjure immediate dramatic resonance. It generates a film-like freneticism as each set piece morphs into the other.

He also relies on a full-bodied visual vocabulary by quoting curated imagery plundered from art history: the towering slabs hover open, as if divinely ordained, to reveal glimpses of the Ammonites decked out in Hogarthian baroque excess and sumptuously lit by candlelight.

By contrast the Israelites are clad in sober and sombre puritanical grey. Jephtha is as much a religious leader as a military one, with his Rasputin-like facial hair and dark robes. One sequence evokes the spiritual yearning of a William Blake illustration as he kneels before an apocalyptic red sun that transforms into an omniscient eye. Judgement is upon him.

Allan Clayton’s effortless vocal muscularity is once again on full show as he returns to Covent Garden to play the title role. Handel’s music promises less psychological meat on the bone for him to chew on than his previous outing as Peter Grimes. But Clayton’s Jephtha, Jennifer France’s velvet voiced Iphis, and the rest of the superb supporting cast and chorus, never fail to find concrete weight in each note alongside Laurence Cummings’ intricately skilful conducting.

Handel purists might scoff at the deviation from the opera’s ending original somewhat more fantastical finale in which an Angel emerges as a Deus Ex Machina. But grounding the characters in the sweaty depths of human psychology is one that pays off. The focus is firmly on us, how our knotty humanity anchors us to Earth despite our hankering for the divine.

That emphasis, coupled with the setting and themes of religion and violence, makes it impossible for resonances not to emerge with what is happening in Israel and Gaza today. The opera steers clear of religious iconography, but a particularly haunting sequence sees cold white light fill the entire room when Jephtha calls his people to war. It feels like a mirror held to the audience who are caught in its ghostly glow. Those who claim opera is irrelevant could not be more wrong.

Jephtha plays at the Royal Opera House until 24 November

Photo Credits: Marc Brenner

Reader Reviews

Videos

.png)