Review: Saariaho's SOUND, Directed by Sellars, Says Yes to Noh at White Light Festival

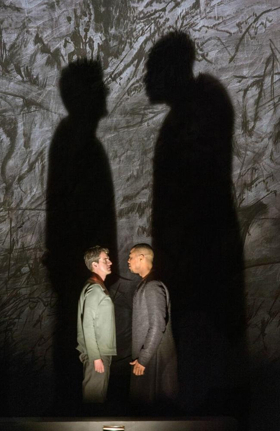

Photo: Ruth Walz

With a formidable cast of three, and a brilliant ensemble of voices and instrumental musicians, Kaija Saariaho's ONLY THE SOUND REMAINS swept through town last weekend, created with director Peter Sellars. Once again, she left us in awe of how she can fill an impossibly large theatre with what seems on paper to be the tiniest of works.

At first glance, SOUND would seem to fit comfortably into your living room (or at least a living room that is bigger than the average Manhattan apartment's)--as Saariaho's L'AMOUR DE LOIN seemed scaled to anyplace that wasn't the mammoth stage of the Met. There, however, it filled the house in ways that wouldn't seem possible.

This time around, in more intimate surroundings--Jazz from Lincoln Center's Rose Theatre--it brought us up close and personal to the characters in a pair of stories based on Japanese Noh plays as seen through the lenses of Ezra Pound and Ernest Fenollosa, the translator/adaptors.

The composer had previously worked with texts by Pound when she was in residence at Carnegie Hall around a decade ago. She was attracted to his CANTOS because they "left a lot of room for the music" and deciding she wanted to continue the collaboration (if you can consider a "collaboration" with someone who's dead and can't disagree with you). Her real collaborator is, of course, Sellars, who was at his finest here; he never overplayed when a simple move would do and was crucial in helping the cast bring out the million nuances of Saariaho's music.

After discussing the idea of taking her interest in Pound further with Sellars, she decided on two Noh-based plays, TSUNEMASA and HAGOROMO, adapted by the poet from Fenollosa's translations. (Sellars is quite knowledgeable about Noh theatre, according to the program notes.) Both deal with the interaction between the human and supernatural--as does all Noh theatre--but their approaches are different.

Neither work has a complicated story but is quite straightforward, with just enough details to have a stunning effect on the members of the audience. Both are staged in front of a simple, abstract backdrop (set designer Julie Mehretu), with the subtlest of lighting (and shadow) design by James F. Ingalls and sound by Christophe Lebreton. Robby Duiveman did the Asian-inspired costumes.

The first, ALWAYS STRONG, is "somber and harrowing" (as Saariaho described it in the program notes)--the interchange between a priest and ghost of a dead soldier. The music was composed specifically for countertenor Philippe Jaroussky, bringing out darker colors in his ethereal voice, and the result is completely enrapturing for the listener. On the other hand, bass-baritone Davone Tines brought an earthy, anything-but-angelic contrast to Jaroussky; his voice thrilled, rich and full bodied, and was as intense without ever turning to histrionics.

The second piece, FEATHER MANTLE, not only presents rich opportunities for Jaroussky (as an angel) and Tines, with vocal lines that "reach for the light," but for the brilliant dancer-choreographer, Nora Kimball-Mentzosis. She was absolutely sensational as the moon spirit trying to convince a fisherman (Tines) to return the feather robe--her robe--he found and has taken, which she needs to re-enter heaven. (In fact, I thought Saariaho saved some of her best music for the dance.)

Though the soloists were superb at every juncture, one cannot say too much about Saariaho's unusually substantial and ravishing writing for the ensemble of voices and instruments. They were critical to the overall effectiveness of the evening, under the superb musical direction of Ernest Martinez Izquierdo.

The Theatre of Voices--soprano Else Torp, alto Iris Oja, tenor Paul Bentley Angell and bass Steffen Bruun--dazzled at every turn, with Torp and Bruun particularly marvelous. The strings of Meta4--violins Antii Tikkanen and Minna Pensola, viola Atte Kilpelainen and cello Tomas Djupsjobacka--along with the virtuosic Eija Kankaanrant on kantele (a Finnish plucked instrument), Camilla Hoitenga on flute and Heikki Parviainen on percussion, brought the amazing palette that Saariaho has created to vivid life, without ever overwhelming Jaroussky and Tines.

I sometimes feel that the music composed for new opera doesn't really seem to need staging at all and, in fact, might be better served as vocal pieces (in concert, for instance, with an instrumental ensemble). ONLY THE SOUND REMAINS, in its sensational US premiere at the White Light Festival, never left me thinking that for an instant.

Reader Reviews

Videos