Review: Finding GOLD as the Met's Ring Cycle Begins Anew

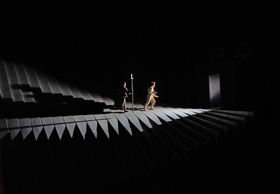

Nibelheim. Photo: Ken Howard/Met Opera

If Robert Lepage's production of Wagner's Ring Cycle (formally, DER RING DAS NIBELUNGEN) had worked as smoothly when it opened in 2010 as it did at this season's marvelous premiere of its prologue, DAS RHEINGOLD, on Saturday afternoon, there probably still would have been complaints.

They wouldn't necessarily have been about its focus on technology (which has been hit or miss in some performances), but that, in its own way, it was a very traditional approach: a straightforward telling, over four nights, of the struggle for the ownership of the magic ring of the title, which grants domination over the world. Personally, I liked the storytelling, though I thought it could have been done with less Cirque de Soleil (another Lepage association) up its sleeve.

The trouble with the production has never been the singers or the orchestra but the "machine"--the 45-ton, computerized system of movable planks that dominates the physical production in conjunction with intricate projections to propel the story along with cinematic speed. When it works well--as it did on Saturday--it is a marvel that provides visual thrills to go along with the fine singing, from the entry of the Rhinemaidens swimming in the river's waters, pebbles moving as their tails swished, to the grand march of the gods to their new home, Valhalla, as the opera ends.

Grimsley. Photo: Ken Howard/Met Opera

But from the productions' earliest performances (along with RHEINGOLD, there is DIE WALKURE, SIEGFRIED and GOTTERDAMMERUNG, all using the same planks with different projections), there have been glitches galore with the technology, distracting from the magic on stage--created by Canadian director Lepage with his creative team of Carl Fillion (set design), François St-Aubin (costumes), Etienne Boucher (lighting) and Boris Firquet (video).

The "machine" has taken a bad (but justifiable) rap for its breakdowns--I remember a seemingly endless wait before a WALKURE--and it has also become a case of "once bitten, twice shy" for some of the singers. In numerous places, they step tentatively on the shifting planks, perhaps worrying whether they would (literally) be thrown for a loop.

In short, is all the anxiety worth the final product? Yes--and no.

Jamie Barton (c.), Norbert Ernst, Dmitry Belosselskiy

and Greer Grimsley. Photo: Ken Howard / Met Opera

That opening scene with the Rhinemaidens (the wonderful trio of Tamara Mumford, Samantha Hankey and Amanda Woodbury) sets up the whole tetralogy, as they taunt the dwarf Alberich (an exciting debut for Polish baritone Tomasz Konieczny), who would be happy to hook up with any of them but hasn't a glimmer of a chance.

Soon, he is distracted by a different kind of glimmer: from a cache of gold, of immeasurable value, that the mermaids are guarding. The person who possesses it will rule the world, once it is forged into a ring. The catch: the owner it must renounce love. Alberich figures that the possibility isn't very likely for him anyway, so the choice is a no-brainer, as he steals their treasure and runs off.

Switch to the realm of the gods, headed by Wotan (the firm and fearsome bass-baritone Greer Grimsley, capturing his greed) and his ever-suffering wife Fricka (the smooth-as-velvet mezzo, Jamie Barton, in her Wagner debut at the house, as the goddess of marriage).

Howard/Met Opera

They have a problem with their contractors (doesn't everybody?), two giants, brothers Fafner (the sonorous bass Gunther Groissbock) and Fasolt (the ringing bass Dmitry Belosselskiy), for the construction of their new stately home. The work is done and they demand the payment promised for the project: Freia (soprano Wendy Bryn Harner, with voice to spare), who is not only Fricka's sister but provides ever-lasting youth for the gods with apples from her garden).

Previously unaware of the deal made by Wotan with the giants, Fricka and her brothers Froh (the commanding tenor Adam Diegel as the god of spring) and Donner (baritone Michael Todd Simpson), god of thunder, are enraged at the thought.

While Wotan says he has no intention of handing her over, he has no good alternative until the demigod (of fire) Loge (a crisply sung, smartly acted--a power to fear--debut for tenor Norbert Ernst) comes up with a suggestion: steal the Rhinemaidens' gold from Alberich. Wotan warms to the idea instantly and the two go off to Nibelheim (in another great visual from the "machine" and projections), the underground home of the dwarf.

There, they find the Tarnhelm--a magic helmet created by Alberich's brother Mime (a finely wrought, bullying performance by tenor Gerhard Siegel) that transforms the wearer into any form he wants. They trick Alberich into turning himself into several creatures and, finally, into a toad, which they capture, with Loge taking the Tarnheim for himself, though Wotan only has eyes for the gold ring.

Without the helmet to hide him, Alberich is easily overpowered by Wotan and Loge; but Wotan is overwhelmed by the promise of power and decides that he must have it for himself. He hands over all of Alberich's gold to the giants, except for the ring, which he cannot bring himself to part with, but the giants are firm about getting it.

The arrival of mezzo Karen Cargill as Erda, goddess of the earth, with her rich and firm voice, stops Wotan's double-dealing in its tracks (ah, to have her in Washington right now!). She puts the fear of god(dess) in him, warning that keeping the ring will bring about the end of the gods. Wotan wavers at first but soon hands it over to the giants--a good move, it , because it triggers Alberich's curse, as Fafner kills his brother as they argue over the treasure.

Freia makes her escape, as Donner clears the air with thunder and lightning, and Froh conjures a rainbow. Here, the "machine" accomplishes its final coup de theatre for the day, with the rotating planks being transformed into a bridge that the gods take to the new home built by the giants, which Wotan dubs "Valhalla." Everyone (were there body-doubles?) joins the procession except for Loge, who is left behind, being a half-human. But, as the curtain goes down, he seems to know that he will have the last laugh.

For the most part, conductor Philippe Jordan and the Met orchestra kept things moving like a finely tuned machine (not "machine"), except for some odd sounds that came from the horn section.

The next installment, DIE WALKURE, arrives in two weeks, with the much-anticipated house debut of Christine Goerke's Brunnhilde. It's not a matter of "will she or won't she?" but whether the technology will cooperate with the art surely to be on stage.

Additional performances of DAS RHEINGOLD will take place on March 14, April 29 and May 6. Curtain times vary: complete schedule here. The production runs about 2-½ hours, with no intermission.

Tickets begin at $25; for prices, more information, or to place an order, please call (212) 362-6000 or visit www.metopera.org. Special rates for groups of 10 or more are available by calling (212) 341-5410 or visiting www.metopera.org/groups.

Same-day $25 rush tickets for all performances are available on a first-come, first-served basis on the Met's Web site. Tickets will go on sale for performances Monday-Friday at noon, matinees four hours before curtain, and Saturday evenings at 2 pm. For more information on rush tickets, click here.

Reader Reviews

Videos