BWW OperaView: Calling HAMILTON by That Dirty Name

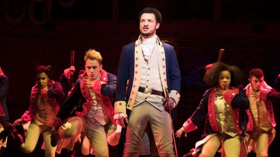

HAMILTON. Photo: Matthew Murphy

When Stephen Sondheim was asked was asked about whether his great musical drama SWEENEY TODD was a musical or an opera, he once responded, "When it's done in a theatre, it's a musical. When it's done in an opera house, it's an opera." (His answers to the question have waffled over the years, sometimes calling SWEENEY things like a "black operetta," etc.)

Well, then, what about HAMILTON, the musical sensation of our time? Is it (gasp!) an opera waiting to emerge? The question crossed my mind during intermission when I finally caught up with Lin-Manuel Miranda's magnum opus last month in London, where it's a whopping success. (But it hardly seems the money-printing machine it is in the US: You can still manage to get a good, reasonably priced seat there.) The thought of HAMILTON billed as an opera titillated me and, yet, didn't seem so far-fetched.

Think about it: If it had premiered at one of the opera companies in Philadelphia or Santa Fe or Minneapolis or St. Louis (with the right director, of course) instead of the Public Theatre in NY, would HAMILTON be that wildly sought-after, mythological beast: the work that would finally get young audiences into the opera house night after night?

For a definitive answer, unfortunately, I guess we'll have to wait a hundred years or so, until HAMILTON, the musical (for now), finishes its Broadway life and an opera company picks it up and sees what different kinds of voices and a giant opera stage do for it. I wouldn't bet against it. After all, how far are the rhythms of rap from the patter songs of Rossini--except that you have to pay close attention to the words in the opening of HAMILTON to have the story laid out for you rather than simply sit back and enjoy BARBIERE's delicious buffa?

One can't deny that today's opera scene--and what makes an opera--is a far different one from the past. Today, works that had long been embraced as musicals have found their way into the opera house: Bernstein's CANDIDE, Gershwin's PORGY AND BESS and Kern's SHOWBOAT, among others. And, of course, there's Gian Carlo Menotti, whose AMAHL AND THE NIGHT VISITORS came from television (and became an annual Christmas event for NBC) and THE CONSUL (which chalked up a staggering 8-month run on Broadway), among others, before finding their places in opera companies.

In the American arena, the number of composers who have chosen to embrace the opera medium for story-telling is enormous--with no little emphasis on the "story-telling" side. Someone might come to hear the latest opera by, to name a few, Kevin Puts (SILENT NIGHT and ELIZABETH CREE), Missy Mazzoli (BREAKING THE WAVES and PROVING UP), Huang Ruo (AN AMERICAN SOLDIER and DR. SUN YAT-SEN), Paul Moravec (THE SHINING and SANCTUARY ROAD) or Du Yun (ANGEL'S BONE) for the music. Yet it is difficult to separate the successes of the works from their pithy librettos by, respectively, Mark Campbell, Royce Vavrek, David Henry Hwang, (again) Campbell and (again) Vavrek, even though the Pulitzer Prize Committee continues to do so.

I'm sure there'll be much eye-rolling among opera snobs who debate the fine line between what's an opera, an operetta, a musical, musiktheater. But with the 2018 Pulitzer Prize in music going to Kendrick Lamar for his hip-hop album DAMN, it's hardly as implausible as it might have seemed even, well, six months ago for HAMILTON to gain long-hair status--and for opera companies to drool at the possibilities.

Comments

Videos