Feature: The Long Journey Home

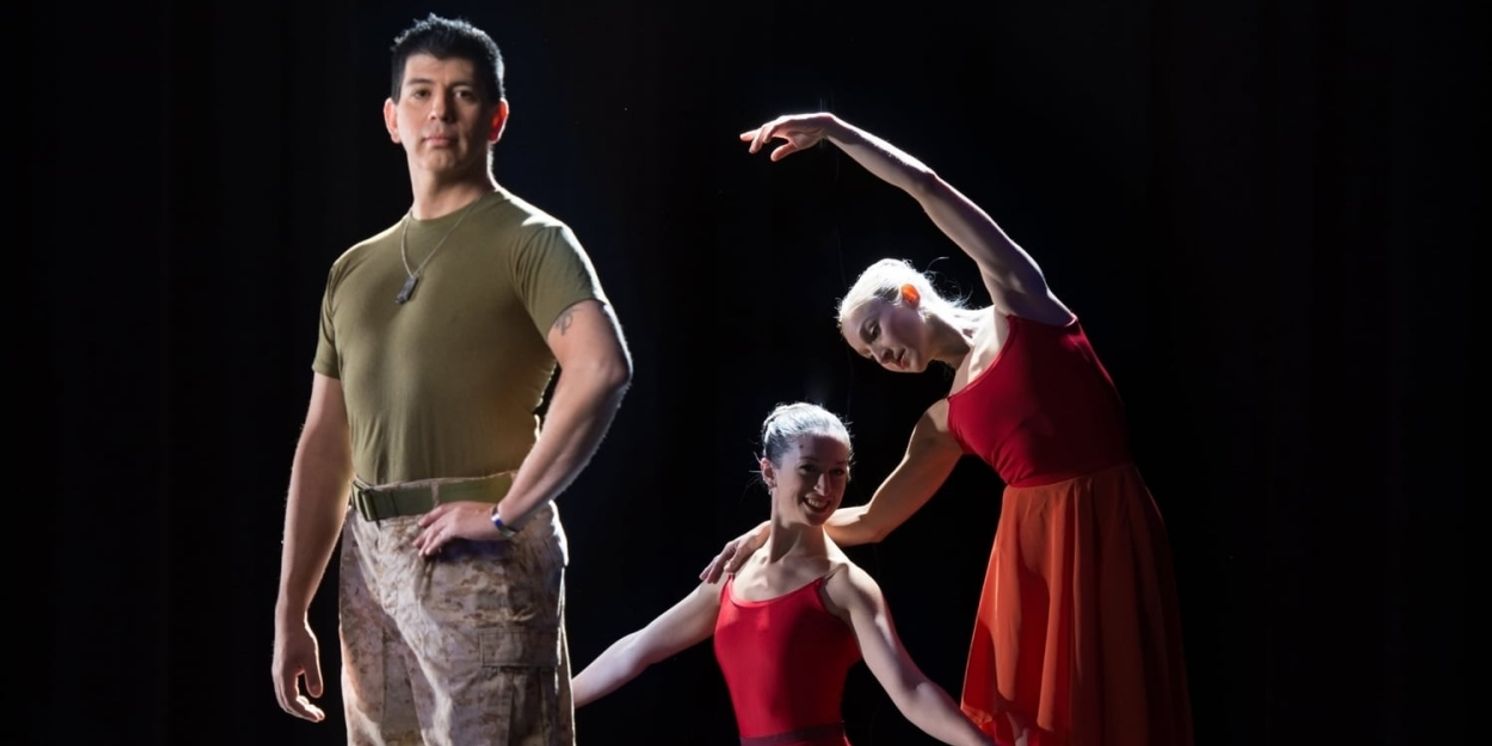

Dancer-turned-Marine-turned-choreographer Román Baca founded the contemporary dance company Exit12 to help those affected by war find their true homecoming in dance.

Standing in a rehearsal room aboard the Intrepid Sea, Air and Space Museum, haloed by the sun setting behind an American flag flapping in the wind off the Hudson River, Román Baca gives his performers their mission: They must complete their choreography for a special Memorial Day weekend performance that’s just five days away.

Baca is the co-founder and director of Exit12, a contemporary dance company that uses the dance theater to inspire conversations about the theater of war. A dancer-turned-Marine-turned- choreographer, Baca is uniquely suited to meld those two worlds together and has become a pioneer in the military veteran art genre. With his company, he not only choreographs works that represent the harsh realities of conflict, he also invites veterans and refugees to create and perform alongside his professional dancers. In Exit12’s latest show, “Truth’s Colliding” premiering May 26th onboard the Intrepid, Baca has invited two dozen individuals affected by global conflict to share their experiences to create an evening-length performance about the effects of war.

While addressing his dancers, Baca stands straight and tall -- a vestige of time spent standing at a ballet barre or standing at attention -- and speaks with the confidence of a military leader advising his platoon on the eve of a nerve-wrecking mission. Only here the anxiety comes not from crossing enemy lines, but from remembering choreography and finding costume pieces and perfecting steps.

The company dancers, all of whom have the same or similar classical training as Baca, are performing alongside “civilians” -- non-dancers -- who have been touched by war. Baca watches them, offering encouraging words or feedback, but for the most part he is quiet and thoughtful. He’s nervous, too, of course, but he has been working with dancers and those touched by war for more than a decade now. While he’s anxious for it all to come together, he understands and respects the impact of the space he’s created.

“There’s something powerful that happens when a military-connected individual experiences the arts,” Baca reflects. “I’ve seen the arts unite disparate populations in meaningful and tangible ways. I’ve seen it erode the borders between people. That’s what keeps me going.”

Baca founded Exit12 with his wife, Lisa Fitzgerald, a professional dancer, in 2007. At that time, Baca was fresh off a tour of Fallujah, Iraq where he served as a machine-gunner and fire-team leader for the U.S. Marines. He was looking for a creative outlet to heal from his experiences in armed conflict and found that returning to his dance roots allowed him to use movement to process his trauma.

Of course the story isn’t that simple.

Baca was 25 when he joined the Marines and, in bootcamp, didn’t tell anyone that he’d spent the past decade training and performing as a professional ballet dancer in his native New Mexico. Then, one evening, he received a care package that included pictures of him dancing. A few of his fellow Marines started looking over his shoulder curiously. Baca recalls two of them finding his life before the military cool, while a third Marine who saw the photos never spoke to him again. Baca, fearful of stigma, decided then that he couldn’t tell anyone he danced. He chose to let his performance and prowess in the Marines become his reputation. Slowly, the Marine became his identity.

Baca joined the Marines because he wanted to serve others, and also because he craved the physical and mental challenge it offered him. “I was used to getting yelled at by Russian ballet teachers, or knocked around and manipulated by dance masters all over the world, but the Marines were still a learning curve for me,” Baca says. “I wanted to prove that I could do it.”

Baca joined the Marines because he wanted to serve others, and also because he craved the physical and mental challenge it offered him. “I was used to getting yelled at by Russian ballet teachers, or knocked around and manipulated by dance masters all over the world, but the Marines were still a learning curve for me,” Baca says. “I wanted to prove that I could do it.”

The Marines, Baca says, taught him that if he went deliberately, decisively and aggressively in the direction that made him the most afraid, usually things would turn out positively. That fearlessness, resilience and grit were comforting for someone who’d grown up in a turbulent home environment and spent years fighting against his instinct to freeze in the face of danger. With the military he channeled his focus and drive -- the same things that benefited him in the ballet world -- into something that appeared strong and purposeful and aggressive.

“Military training is designed to make a person into a killing machine,” says Adrienne de la Fuente, Exit12’s company manager and the daughter of a former Army captain. “It’s trying to remove the thoughts behind the eyes when asked to pull the trigger. When you leave the military there’s no way to get the thoughts back into the body.”

It’s not uncommon for veterans to struggle to return to civilian life. War gives a life purpose and without it, one can drift, directionless. Upon returning home from Fallujah, Baca tried to stave off that enervation by doing what society deemed “the right thing.” He bought a house, he settled down and he took a job doing technical drafting. It’s what his grandfather and uncles -- also military -- had done. But so-called “normal” life couldn’t eclipse the misery Baca was feeling. The happy-go-lucky man he’d been before the war was gone and in his place was someone who was angry and hypervigilant and unable to express himself.

“I could see how much he was struggling to come back from the war,” says Fitzgerald. “I didn’t understand the war, or even what he was dealing with. But art was such a huge part of my life, that when he said ‘I want to start a dance company’ I said okay.”

Exit12 was created first as a space for Baca to explore his experiences in Fallujah through dance. One of the first stories he told was his own. In Fallujah, he was working a checkpoint where, armed to the teeth, he’d pull over cars and inspect them for vehicle-borne IEDs. He stopped one car and, upon looking in the backseat, saw a woman holding a baby. He had orders to force everyone out of the car, but he didn’t want to scare a woman and her child by forcing them to stand with guns trained on them. In a fit of conscience, he let her stay in the car.

“I was chewed out aggressively for that,” Baca says, laughing about it now. “But the car search is one experience I chose to put on stage because it stayed with me. It’s a way to show how art takes on a larger meaning and shares with the world what [war] looks like.”

Exit12 not only draws inspiration from Baca’s time in Fallujah, it also uses poetry or spoken word from other veterans, military families or refugees to inform the choreographic storytelling. To help embody these experiences, the company encourages those affected by war to explore the emotion behind the memory they’re describing and then assign a movement to it. This is often daunting, especially since war seeks to blunt emotional responses; to become numb is to survive. But reconnecting to the emotion is, de la Fuente observed, when healing begins.

“I saw how this helped Román,” de la Fuente says. “I see how this helps the vets, the Gold Star families, the refugees. The pieces we put on are so powerful because they’re so personal.”

Exit12 also uses what it calls “repurposed movement” to help veterans reconnect with their bodies and minds through dance. In this practice, veterans are asked to release any ingrained physical movements -- marching, carrying a weapon, standing at attention -- and begin to believe that their motions are not predetermined. Every step doesn’t have to be with dogged purpose, every time they pick something up it doesn’t have to be with the intent to defend.

To Fitzgerald, this is hard work and she values building that trust with veterans. “We’re not asking anyone to share their experience before we’re asking them to be the present in the room with us,” says Fitzgerald. “You can’t share and be vulnerable if you don’t feel accepted. We work to create a welcoming space for everyone.”

To Fitzgerald, this is hard work and she values building that trust with veterans. “We’re not asking anyone to share their experience before we’re asking them to be the present in the room with us,” says Fitzgerald. “You can’t share and be vulnerable if you don’t feel accepted. We work to create a welcoming space for everyone.”

While an Exit12 piece may feature a mimed military salute or gun-toting forward march, it’s not attempting to be dance-driven Forrest Gump -- or any other narrative-centered war story. Rather Exit12 is, at its core, an exchange of sense memory. Audiences are shown an embodiment of one person’s experiences with combat, and then asked to call upon their own sense of duty and pain and resiliency to form a new understanding of what it means to serve. This is the unique alchemy of Exit12 and yet for those who have never dared to combine two things as disparate as military service and ballet, it is strange magic.

Baca recalls an initial resistance from the military community that he attributes to a misunderstanding of the work. But, once veterans knew that Exit12 was endeavoring to tell honest war stories, they began to realize the power it held. Here was a way for them to voice what it's really like to fight in a war and then ask audiences -- the very people who vote and influence foreign policy -- to engage with their reality. For artists, Exit12 reaffirms that a creative work has an impact, even if other dance companies still don’t know what to do with a ballet inspired by a trauma so many people will never experience.

Whether the dance or the military worlds ever understand Exit12 is not the focus of the company’s work. The company is here to serve and create. Baca has dedicated his life to understanding how art heals. He received his MFA in choreography from Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance in London and focused his thesis on methodologies of choreographing soldier’s stories to provoke empathy in audiences. He is a PhD Candidate at York St. John University where he is investigating the military human through the arts. He also works with Bravo 22 to connect veterans to art. He even had his full-circle moment when, in 2012, he returned to Fallujah -- this time with ballet shoes and music instead of guns and ammo -- to host a dance workshop for Iraqi youth.

Back in the rehearsal space, Baca watches his dancers again. Soon he will help them put their dance to music, giving a rhythm to their movements and to their memories. It’s another step in the process of exploring what it means to journey through trauma toward healing. Where this journey ends, or if it ends, is different for everyone. Baca’s grateful to be along for the ride.

“I can’t imagine doing anything else,” he says. “To be in the studio working with veterans to share their lives with an audience, to have discussions about [what they’ve lived through] is beautiful and spiritual.”

Outside the window, the setting sun catches on the American flag again. For the majority of rehearsal, the flag has flapped back and forth as if it, too, is dancing.

Videos