Does 'Belly Dance' Have A Place In Intersectional Feminism? Dancers of Color Speak Out!

As a dance that was created by women of color, is amenable to a wide diversity of bodies, and is often described by its disciples as "empowering" and "liberating" one would think that "belly dance" is a stronghold for intersectional feminism in the dance world.

However, the jury is still out on that one.

It should be noted that true feminism shouldn't need the qualifying word "intersectional" as true feminism is inherently intersectional. Its goal of social, economic, and political parity for all is driven by the experiences and needs of all women, girls, and femmes and is ultimately liberating for men as well.

However, the term "intersectional feminism" is used to define feminism that embodies the aforementioned qualities thanks to the failures of what is considered mainstream feminism; a feminism that still benefits from eurocentrism, racism, imperialism, and other nefarious pillars of our current social, economic, and political reality.

If mainstream feminism can be blinded by these privileges, perhaps it shouldn't be surprising that mainstream belly dance communities can also be. After all, it is no secret that the majority of the money, fame, and influence within the belly dance scene today is held by women who are not "of color" or women of color who are not easily identified as such.

Is there a way to create a more inclusive, authentic, empowering belly dance world for all?

In order to find out I spoke to several women, who are accomplished performers of Middle Eastern and North African dances, about their perspectives, particularly as dancers of color in the West.

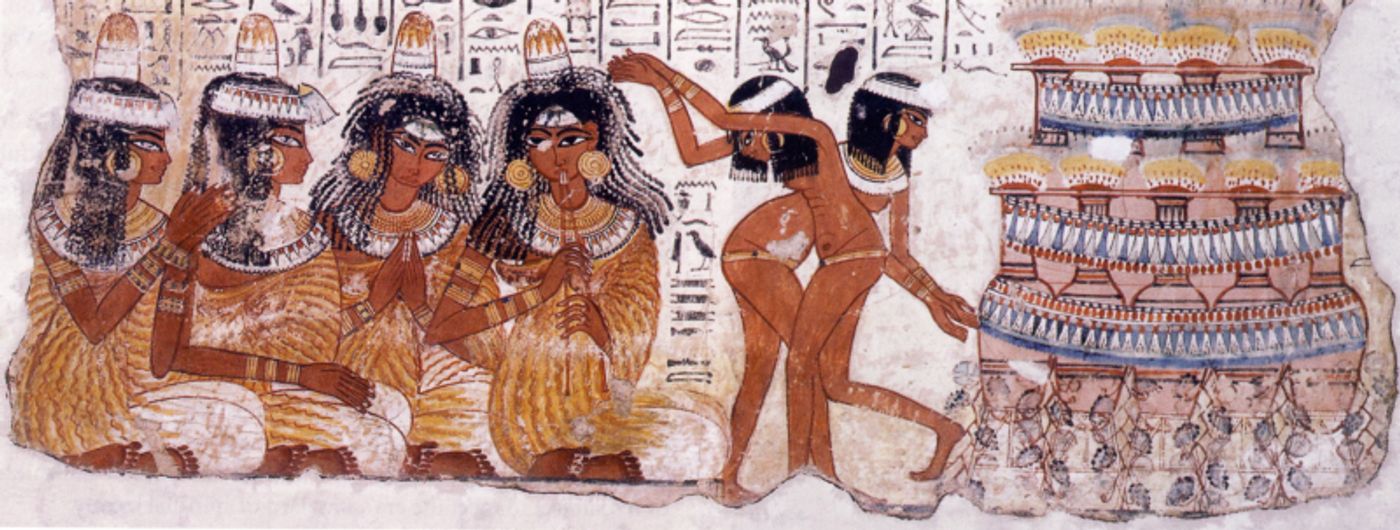

But first, let's define "belly dance." What is known as belly dance today is often a fusion of dances predominantly from North Africa and the Middle East. Popular claims link the roots of belly dance to ancient Egypt and archaeology proves that dance was very important in ancient Egyptian life.

However, although there were several millenia of indigenous African reign, it is important to note that Egypt has had an influx of foreign conquerors, traders, and etcetera for at least 2,000 years. The inevitable intermixing of the indigenous population with surrounding cultures makes it difficult to pin down one origin point for belly dance but Egypt is definitely a Mecca for the dance today and the Egyptian dance Raqs Sharqi is generally considered synonymous to belly dance.

However, scholars have observed the survival of ritualistic fertility dances and casual women's dances, the root of several movements in belly dance's vocabulary, in parts of Africa and Western Asia outside of Egypt. Modern belly dance has also been influenced by spiritual dances such as Sudanese Zar and the Guedra of the Tuareg people (in Niger, Mali, and other parts of Northwest Africa), martial dances such as the Egyptian Tahtib and Nubian sword dances, and dances from the Western standard such as ballet and even hip hop.

The nomadic people of Egypt, the Ghawazee, contributed much to the modern performative aspects of the dance as did the Algerian Ouled Nail women by dancing in public with coins attached to their costumes. Women from these groups were displayed by Sol Bloom at the 1893 World Fair in Chicago. Bloom coined the umbrella term "belly dance" for the dances that were being seen for the first time by American audiences.

Belly dance's roots in Eastern cultures, North African cultures in particular, is undeniable. Black and Brown dancers fill the scenes of ancient Egyptian wall paintings and of dance history gems such as Dr. Magda Saleh's 1975 documentary Egypt Dances. So why is it so hard to find Black and Brown dancers making a name and a living for themselves in the modern belly dance scene?

Brandy Heyward is the creatrix of Harlem Hafla, a showcase dedicated to belly dancers of color. She attributes the dearth of dancers of color to the lack of opportunities available to women of color in the dance.

"Orientalist fantasy and European beauty standards are strong in the belly dance world, especially in the West. Dancers of color, particularly dark-skinned dancers, are often not the ones hired to perform, teach workshops, have TV spots, etcetera. There are so many people who've told me they've never seen a Black belly dancer. In spite of belly dance's roots, dancers of color are not what audiences expect to see. The point of Harlem Hafla is to create that visibility and control our own image. The crew, musicians and vendors at Harlem Hafla are also predominantly people of color."

When I asked Brandy about what could be done in response to this issue she responded, "Support dancers of color, hire dancers of color, create opportunities for us. People of color need to do this too-it's important that we create opportunities for ourselves. As dancers, we need to make more of an effort to work together and support one another. If we can support dancers who aren't of color, we can support those who are."

Dancer Rivka Azucumba Isskandreyya, who's been belly dancing since she was 15, agrees there should be more dancers of color in belly dance and attributes the lack thereof to a lack of education about the dance's roots.

"In taking workshops and observing the dance around the world, I've noticed mostly White and occasionally East Asian instructors and performers. When there are Middle Eastern, North African, or other women of color teachers and performers they are rarely darker-skinned dancers.

The impulse to separate belly dance from other African dances comes from the influence of Eurocentrism and colonialism. The embrace of European beauty standards and a lack of historical understanding of the dance's roots leads to fewer dancers of color getting involved with the dance. This is particularly true for Black dancers, as many teachers of belly dance are White women who perpetuate ignorance of the dance. There are definitely White teachers who do know the dance's history but many I've observed do not.

I know several dancers of color, myself included, who were told we didn't have the desired 'look' of a belly dancer, hence we weren't hired for gigs regardless of our talent. When I did troupe work, the colors of costumes and make-up looked good on the other girls but not on me.

I've only recently seen more 'natural' dancers of color; women who embrace their natural hair, their skin tones, and cultures. Obviously, it's a contradiction to do an ethnic dance while trying to look as not-ethnic as possible.

A teacher once reminded me that for every time I allow the discrimination to shut me out of the scene, there is one less beautiful Black belly dancer that the world will get to know. As a social justice advocate, who relies on the arts for healing and communication, I accept the challenge of continued self-reflection and perseverance, in order to develop a louder voice for myself and other dancers who've similarly felt marginalized.

Belly dance is a dance for women to celebrate themselves and each other. I would like for us to bring it back to acknowledging, embracing, and uplifting the dancer regardless of what she looks like."

Dancing since the 1970's, Camila Karam is an African-American belly dancer whose great-grandmother was Egyptian. Also versed in herbology, yoga, and Afro-Brazilian dance she says she's largely ignored inequities and standards of the mainstream belly dance world and created her own look inspired by traditional North African dress and a conscious connection to spirituality.

"Back when I was starting out the White teachers I had said the dancers, from the countries of belly dance's origins, looked more like me than them. Honestly, I feel like I was supported in my dance journey more by White people than by people of color.

However, I do think this is partially because of the very real inequities in the dance world. The lack of opportunities available to Black women has created a lot of insecurity and competition among Black dancers. I want to see more Black women supporting each other. There is room for everyone to succeed.

In the South, another reason many Black women are not supportive is that belly dancers are likened to whores and witches. This mindset comes from the influence of Abrahamic religions and these were forced onto Africans by colonizers. So often people of color, who are in positions to hire dancers of color, are too stuck on dogma to really open their minds. Even those with lots of education and degrees fall into this trap."

When asked about intersectional feminism and belly dance Esraa Warda, an Algerian-born dancer and founder of the North African Radical Education Project, had this to say:

"The world of modern 'belly dance' is not and will not be intersectional until Arab, North African, Middle Eastern, South Asian women are in charge of their culture, how it's distributed, how it's represented, how it's shared. These women are the ones who should be teaching the classes.

There is a HUGE discrepancy between how North Africans interact with the "institution" of belly dance and how Americans and Europeans do. Belly dance, the way it's been practiced and defined by White women, is a hyperbolic manifestation of overtly orientalist perceptions of women of color. It is a highly commodified and commercialized adaptation of Eastern dances that excludes women from the cultures of origin.

Because of privilege and white supremacy, White women have more open access to a culture that is not native to them and find a sense of "freedom" and "liberation" through emulating and imitating Brown women like it's a costume you put on and a lifestyle you adopt. Women of color, who start getting into this industry, need to not to follow the lead of these women. Americanized belly dance isolates the social context, community, informal women spaces, and improvisation inherent to these dances but dancing in the kitchen with no bra, with your cousins and aunts, is where the party is really at!

Sometimes when I go to the Arab cabarets, they bring out a European belly dancer. This happens because dancers from our communities are stigmatized and slut-shamed but when a White woman is a belly dancer, it's 'edgy' and 'cool.' F- that!

I am not a 'belly dancer'. I practice, perform, and teach folkloric North African dance like chaoui, kabaylie, and rai from Algeria and different styles of chaabi from Morocco. I used to dance raqs sharqi in clubs and cabarets when I was younger, but was discouraged and pushed out of it because of my bigger body type. I'm still uncomfortable with the belly dance scene because it's so inorganic and toxic."

Do a quick Google search of "belly dance and feminism" and you'll find articles that mainly consist of:

1. Women defending the artform from notions that it is anti-feminist because it attracts an objectifying male gaze.

2. Women claiming the dance's manifestation in the West is inherently racist and orientalist due to its appropriation by "White belly dancers", and its commercialization by corporate interests, in societies built and sustained by Western imperialism (where negative portrayals of Middle Eastern and African people are common.)

While we've well-explored and expanded upon the second point in this article, I think it's important to also explore the initial, and much more common, argument.

One would think the first point is outdated in a world where a woman's right to agency over what she does with her own body is a fairly recognizable tenet of feminism. However, if the plight of feminist sex workers has taught us anything, we know mainstream feminism can sometimes butt heads with this idea of agency where monetized sexuality is concerned (even if that monetization is necessary for survival under virulent capitalism.)

Belly dancers making the first point have to be careful to not degrade sex workers, or the very roots of belly dance, while elevating themselves. Many dancers in the community have heard things such as "belly dance is not stripping" or "belly dance is sensual, not sexual" ad nauseam.

While it's true that belly dancers are not strippers, in a grab for respectability, the "belly dancers are better than sex workers" attitude denigrates other women and people. It is no better than the attitude that considers belly dance anti-feminist. There is overwhelming evidence that what we now call belly dance is connected to fertility, conception, and childbirth. Therefore, sex cannot be whitewashed from the dance. The argument that "belly dance is sensual, not sexual" does not really even make sense when another quick Google search reveals most dictionaries describe sensuality along the lines of "the enjoyment, expression, or pursuit of physical, especially sexual, pleasure."

While it's important to respect the modern incarnations of the cultures that are found in belly dance's countries of origin, cultures which are often heavily degrading of sexuality, we must also remember that these countries have been beset by Abrahamic religious dogma-and the roots of belly dance are far older than Abrahamic religions. It is entirely possible to express reverence, sensuality/sexuality, and skill in a profound, unique and artistic way through dance. Ultimately, superiority and desperate grabs for respectability often end up hurting dancers, women, and people in general.

Sadly, attempts to legitimize oneself by contrasting oneself against the "trashy" dancers beneath her is still all too common in the modern belly dance world. The experience of performance artist and M.S. Registered Dance/Movement Therapist, Cashel Campbell (formerly known in the belly dance scene as Sapphire), reflects this:

"A male associate of mine, a well-known musician and producer within the Middle Eastern and North African dance community, approached me to do a show he thought would elevate the defining elements of belly dance: beauty, feminine carnality, sensuality, community, divinity.

He described the baring of my breasts as I danced as a touchstone to honor my ancestors. The idea of presenting that kind of naturalness, not commonly understood in societies where the body is a source of shame, ignited a fire within me. I was excited to be whoever I chose to artistically and use my body as I wished but it was naive of me to think that a community, which had not yet resolved issues about its own sexuality and the expression of such, would be willing to embrace someone like me and a show like that.

The show was repeated a few times over the course of a few years throughout New York City. I felt I had stepped into uncharted territory, that I did my ancestors proud. I felt empowered as a woman of color. The statement I made was not just speaking for me but it was outrageous enough to speak for all of the brown skins that had been told they weren't beautiful enough, or they were too dark, or their hair was too kinky, etcetera.

The larger belly dance community, however, wasn't so thrilled. What ensued over the months and years to follow was, plainly put, just hurtful. I walked into many dance spaces, shows, conferences, and community gatherings empathically feeling all of the judgment and disdain that was behind the eyes of women and men who didn't know me from a can of paint. I was told that others had much to say about me and the 'disgrace' I was. The funny thing is, no one, except for one Black woman, had the guts to say anything to me directly.

We live in a moment where all kinds of people are finding the strength to speak up and out about how they have been injured emotionally. Culturally, we live in this delusion of numbness. I say no. I don't want to be emotionally dead. I don't want to feel less. I don't desire to pretend that I could care less when I really do care. I've grown to know that when you cut yourself off from being hurt, pretending to be too fly to have feelings or being too proud to express how you truly feel, you're cutting yourself off from progress. You're cutting yourself off from deepening the relationships in your life. You're cutting yourself off from self-respect which is the construct for how others learn how to respect you. You're cutting yourself off from living richly in the moment."

The belly dance world may still have far to go when it comes to truly embracing, embodying and expressing true intersectionality. Yet endeavors such as Harlem Hafla, The Kandake Dance Theatre for Social Change, and more are paving the way for positive change in the dance world and beyond. As an increasing number of dancers of various colors, cultures, sizes, genders, ages, orientations, and ability levels find the courage to share their experiences, and live authentically through the dance, I have hope that the rich cultural community of belly dance will eventually be at the forefront of the movement toward a more diverse, holistic and inevitably more dynamic and profound dance community and world.

Videos