Review: HARD TO BE SOFT — A BELFAST PRAYER at Irish Arts Center

Oona Doherty's powerful exploration of inner-city bodies runs through January 23

Inner-city bodies move differently. They possess a certain swagger necessary to carry the added weight on their collective and individual shoulders. Urban bodies' movements and gestures act as armor to mask any vulnerability. Like a beast in the concrete jungle, their physicality suggests, "Don't mess with me. I'm dangerous."

Oona Doherty's Hard to Be Soft - A Belfast Prayer, running from January 13-23 at the Irish Arts Center's magnificent new building, rivetingly showcases and exposes the unique physicality of urban bodies. Though the dance show takes its inspiration from the people of inner-city Belfast in Northern Ireland, the performer and choreographer Oona Doherty's hometown, anyone who's lived in cities will immediately recognize the machismo used to protect a delicate human core. That's what makes the work so strikingly relatable and universal - at least to city folks with thick, calloused skins developed to conceal soft hearts.

Doherty performs two solos in Hard to Be Soft - A Belfast Prayer and is joined by Sam Finnegan, John Scott and the Sugar Army, a group of dancers in their teens and early twenties recruited locally by Doherty from the Young Dancemakers Company. Though the cast consists of twelve women (including Doherty) and only two men, it's the women who embody unabashed masculine bravado and toughness convincingly, while the men display the extraordinary delicateness of the human spirit beneath the tough facade.

When Hard to Be Soft - A Belfast Prayer opens, you can smell it before you see anything happen. Three tracksuit-wearing hooded figures gather around a censer as smoky incense wafts through the space, rising up to the top of Ciaran Bagnall's sky-high set that frames the stage ominously like pencil-thin skyscrapers or prison bars. The incredible set transforms into a different architecture with each segment, confining, liberating, or boxing in the performer and shaping their stories. So it's no surprise that Bagnall is also the lighting designer because the moods informed by the set and lighting are so synchronized and precise, they must come from the same imagination.

The first piece is a solo by Doherty with her hair slicked back in a ponytail, face free of makeup and body clad in baggy whites and a gold chain. Initially, the look suggests androgyny until she moves; from the first gesture, it's hard to believe you're not watching a wiry young Belfast lad. Her training, experience and skill leave no doubt that Doherty is a dancer, but what sets her style apart is that she's more of a physical storyteller or an actor whose medium is movement.

But, wait, isn't that what all dancers are? Not necessarily. Many dancers showcase their skills and technique, which may or may not propel a storyline. Doherty's two solos that bookend the segments performed by other artists in Hard to Be Soft - A Belfast Prayer are, more than anything else, intensive character studies. She morphs entirely into the body, mind and spirit of an edgy Belfast toughie to the point where the woman she is disappears, like a masterful character actor.

This intense transformation makes me even more curious to see her Lady Magma: The Birth of a Cult, which explores female sexuality. What an exciting evening a double-header of those two performances would be!

The energy of city bodies with female bravado was on display in the second piece performed by the Sugar Army. It's Doherty's tradition for Hard to Be Soft - A Belfast Prayer to recruit local artists, particularly young dancers, for her Sugar Army. These girls are alumni of Young Dancemakers Company, a tuition-free summer dance ensemble for NYC public high school students who want to create and perform their own original choreography.

Their segment has all of the posturing and attitude of teenage girls from an inner-city high school. Most of the dancers are still in high school, recent graduates, or college-aged, so those feelings live in their bodies. They are expressed fluidly, powerfully and sincerely in their movements choreographed by Doherty. Though masculine machismo is often used to mask vulnerabilities, there's hardly a creature more cruel and vicious than a high school girl, and the NYC Sugar Army demonstrated it's just as hard to be soft for young women.

Wearing brightly-colored track jackets, white tee-shirts, and black pants, each member of the Sugar Army was a standout. Note the names Gianette Dominguez, Mishayla Carcana, Annia Nelson, Nevaeh Davis, Kiana King, Ava Davis, Genesis Perdomo Santos, Harlyn Lopera, Zarina Medwinter, Afsana Jim, and Mireya Rojas - you'll be seeing them again.

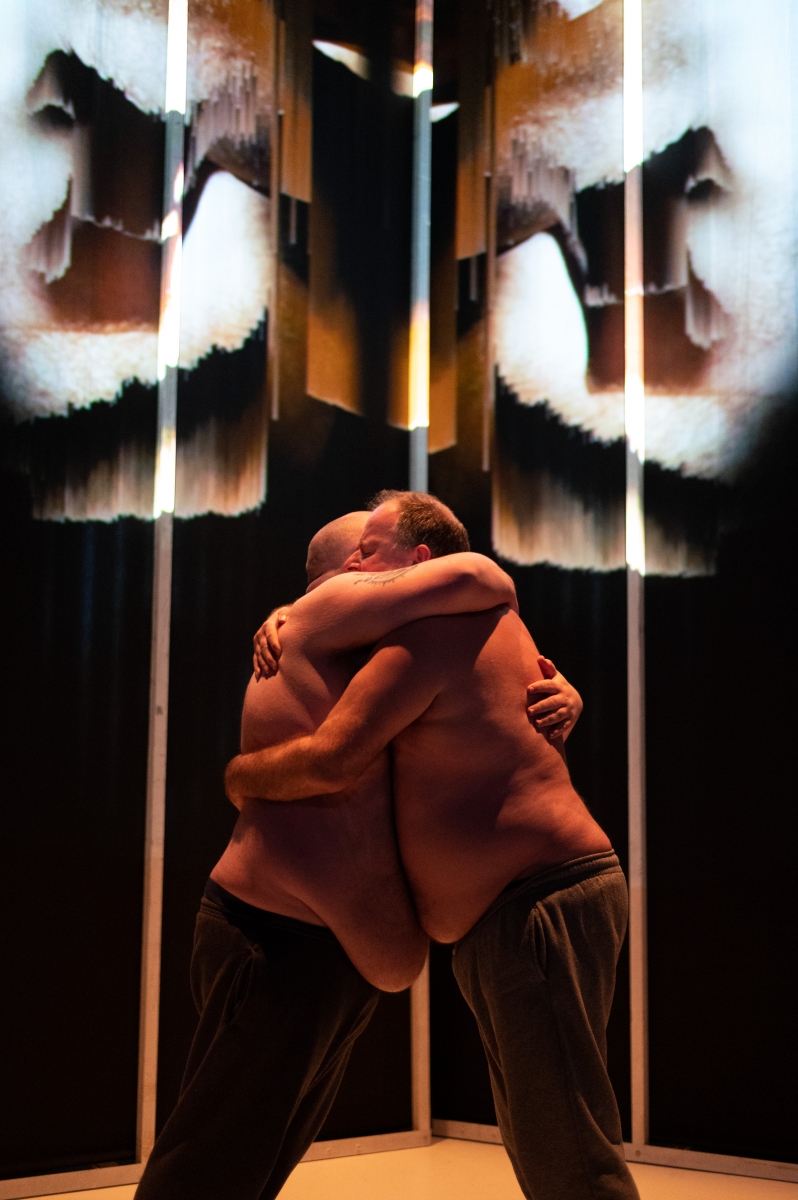

But as compelling as the pieces performed by Doherty and the Sugar Army are, I was not prepared for how utterly transfixed and touched I'd be by the third segment entitled "Meat Kaleidoscope." This was the only piece featuring male urban bodies, not those traditionally seen in dance. The lights are brought low to a dim level of candlelight, like something from a dream or nightmare, and the set opens up to a strange geometric configuration as two robust men face each other menacingly from opposite ends of the stage.

The men are John Scott and Sam Finnegan. Both are portly with sparse hair, broad shoulders and protruding bellies exposed, naked from the waist up. At first glance, in the darkness, they appear to be mirror images of each other, but upon a closer look, Finnegan is a generation or two younger than Scott.

From opposing corners, they approach the other slowly, deliberately and with a mesmerizing articulation that calls to mind Japanese butoh dance. When they finally collide, they lock into an embrace that bears more conflict than comfort. They push the force of their body weight against one another in a way similar to sumo wrestling. This occurs while Jack Phelan's video montage of the two men in a fragmented kaleidoscope flickers above. At one point, the triangulation of their forms seems to make them meld into one grotesque yet beautifully human mass of flesh. This is the soft white underbelly laid bare, physically and emotionally.

"Meat Kaleidoscope" is also choreographed by Doherty, and, above anything else, it shows her range, dynamics, and capabilities as a choreographer who's much more than a one-trick pony. It was the least "dancy" of the pieces but the most powerful and profound. The placement of its following displays of tension and machismo performed by lithe female bodies was further intriguing and poignant, as was the juxtaposition of the stillness in contrast to the quick and jerky movements seen before.

Like the video kaleidoscope, you can project whatever you want to see on the two men, and if it rings true to you, then it probably is. Is it a clash of toxic masculinity, friction between a father and son, a battle with homoerotic feelings, or a face-off with the inner self? Given the name and origin of the performers and creator, it could allude to The Troubles, the decades-long conflict between the Protestant North and Catholic South of Ireland that is the subject of Kenneth Branagh's recent film Belfast. Interestingly, Finnegan and Scott are from the North and South, respectively, so their confrontation could have occurred in real life generations before them to brutal results. That collective trauma lives in the body and is passed on.

To Finnegan, who I had the pleasure of talking with following the performance, it's personal. "John reminds me of my Dad," he told me, explaining that his father has lost the ability to speak, so this exploration is a way that he can physically work through things he'd like to say to him. "I cry before and after every performance," Finnegan confessed. Is this process healing? Does it help him come to terms with these feelings and trauma? Not necessarily. Is it cathartic? Absolutely. In these turbulent times, catharsis may be enough for now or a start.

The only thing about Hard to Be Soft - A Belfast Prayer that unsettled me was the final solo by Doherty sandwiching the guest artists and closing the performance. It was an interesting and well-done piece very similar to her first solo, down to the score by the Belfast DJ David Holmes intermixed with dialogue in thick Northern Irish brogue. What bothered me was the placement. It occurred immediately after "Meat Kaleidoscope" and began with a shock of stark white lighting as Doherty flung herself on the stage floor. "Meat Kaleidoscope" was so affecting that I wanted the show to end there, perhaps with that final solo placed before it.

One doesn't have to be from Belfast to appreciate the themes explored through raw physicality in Hard to Be Soft - A Belfast Prayer. It's beautifully choreographed by Oona Doherty and performed by Doherty, Sam Finnegan, John Scott, and the Sugar Army with as much tenderness and vulnerability as edge and bravado. Anyone possessing a "city body" with all of the collective trauma from an urban environment will recognize and relate to the thick shell worn to conceal any perceived weakness. To experience the show may or may not heal internal conflicts, but it's certainly cathartic.

Reader Reviews

Videos