Review: CONTEMPORARY DANCE FESTIVAL: JAPAN + EAST ASIA Sets the Bar & Demonstrates a New Vocabulary

The year 2019 was off to a rapid launch, and those who can't catch up will be left behind. While the U.S. government is on a shut down, the performing arts world in NYC is pulsing with dynamic, creative expressions. From the Under the Radar and Prototype festivals to Japan Society's Contemporary Dance Festival: Japan + East Asia, the city is overflowing with talent, much of it in service of the visiting presenters looking to book their next seasons (from all over the U.S. and internationally), who are attending the APAP conference and ISPA congress - both of which are getting an unusually early start this year, the first two weeks of 2019, when most people are still recovering from the holidays.

But anyone, presenter or patron, who didn't catch the two-day only Japan Society's Contemporary Dance Festival: Japan + East Asia was severely missing out. The artists presented from Japan, Taiwan and Korea performed works of contemporary dance so tastefully innovative, remarkably unique, emotionally captivating and utterly mesmerizing that they demonstrated what seemed to be an entirely new language of physical expression and set the bar extremely high for other contemporary dance companies on any side of the world. Out of the many interesting and provocative dance works I saw in 2018, these three topped them all in terms of utter inventiveness, extraordinary technique turned on its head (sometimes literally) and complete commitment from the performers.

American artists be warned - you've got some serious competition from the East and had better step up!

Much of the credit for the impressive, highly selective line-up is due to Japan Society's Artistic Director responsible for the robust programming, Yoko Shioya, who accepted the distinguished honor of the 2019 Bessies Presenter Award for Outstanding Curating on January 6th.

This dance event, Japan Society's longest-running program, has been through several important incarnations and evolutions to bring it to what it has become today. It was initially launched in December 1996 as Contemporary Dance Showcase from Japan. In 2008 it broadened its scope, morphing from a showcase of dance from not only Japan, but also from other parts of East Asia.

This year, the 18th installment, marked the biggest transformation to date: not only is the work presented sourced from all of East Asia and Japan, but it is biennial rather than annual, allowing the time for the appropriate research to pinpoint the most outstanding works from both emerging and established choreographers, offering New York audiences and presenters the absolute top, most buzzworthy and talked-about choreographic creations being shown in Asia today. To reflect this, they altered the nomenclature to better suit the level of talent and prestige of the work, now calling the two-day event Contemporary Dance Festival: Japan + East Asia.

But enough of the journey, let's move on to the work itself. The opening piece, Kids, was choreographed by Kuan-Hsiang Liu and featured him and two other excellent female dancers (Yu-Yuan Huang and Wan-Lun Yu) representing Taiwan. It was described as a tribute to his late mother, her death and fight against cancer, punctuated by moments of peace and serenity. Liu recorded his mother's voice in her final stages of communication and comprehension, so some of their dialogue is used (in voiceover with English subtitles projected) in the physical exploration of this deeply intimate and painful experience.

It began with the choreographer/conceiver/artist himself, sitting on stage in an inviting, warm and welcoming way as if in his own living room, addressing the audience directly after the usual announcements to silence and put away our devices. Instead, he urged us all to ignore the instructions, take our cell phones, find a person (or thing) we love and look at it for two minutes. Liu has a certain gentleness to him that instantly puts one at ease. During that time he asked us to ponder, "If this was their last day, what question would you ask them?" This shocked the attendees out of the torpor of the day and set up a personal connection to what was about to be witnessed. But that was where the gentleness ended. The rest of the expedition into death and dying, a life lived and personal histories, was relentless, consuming and alternatingly painful and transcendent - much like grief, loss and death itself.

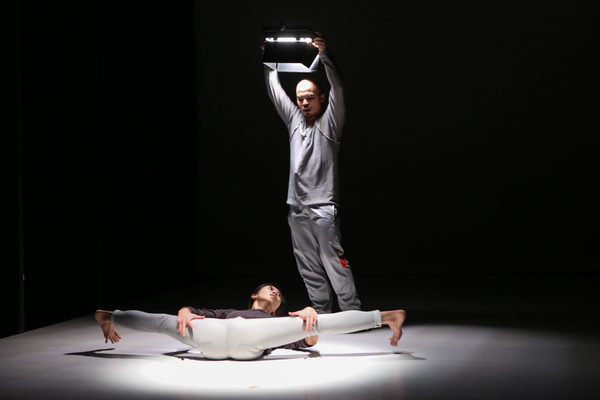

The piece was performed in light and shadow, by Liu who cast the spotlight on the female dancers, creating exaggerated specters on the walls as he, himself, danced with the light-bearing apparatus, not as a passive voyeur but one who intends to reveal the truth. He also shared the aforementioned recorded intimate conversations with his mother in her last days - exchanges that might seem arbitrary to the listener if not for the context of their significance. But just as that tenderness and humanity made the piece so resonant and compelling, the physical expressions made Kids revelatory, poignant and groundbreaking.

While exploring the inner worlds of a person nearing the end of their life, Liu tasked himself and his dancers to investigate near-impossible physical feats with the fluid ease of a Surrealist painting. Their twisted, broken-bodied interpretations appeared utterly natural in their grotesqueness, like something encountered in a dreamscape, or more likely a nightmare. The three displayed acts of testing the body's limits, from bizarre contorted splits to low acrobatic turns and tumbles, to a stack of the trio, legs and arms awkwardly intertwined, primal screams proclaiming their pains, without ever seeking applause for their almost inhuman achievements.

The physical vocabulary was something so entirely new it is still hard to define, but its impact is resonant. The journey to this deeply vulnerable place of grief (Liu is no stranger to communicating his losses onstage, his first work from 2014, Hero, was devoted to the memory of his deceased father) was brought to a bodily crescendo in the final scene when Liu appeared in a flesh-colored dance belt - giving him the appearance of being naked, exposed and stripped of any worldly attributes - and contorted his physique into such strange, alien and obscure positions expressing fear, panic, struggle then eventually acceptance and peace that it seemed he entered the world of death itself and came out the other side to tell the tale.

The next performance, Silver Knife by Goblin Party from Korea, was another innovative work of contemporary movement with a more playful and at times downright humorous side to it. Silver Knife is a reference inspired by the traditional Korean 'Eunjangdo' knife - an object of many uses and meanings, as it was a emblem of chastity also used to fend off predators or commit suicide. Such a layered and complex symbol served as an appropriate talisman for the piece that dove deep into the contradictory expectations of women, particularly Asian women. Goblin Party, founded in 2007, uses the Korean goblin as its mascot, appropriately so for they are known in folk tales for their extraordinary strength and mischievous behavior. The same could be said of the four captivating female performers who were also credited as co-creators Sungeun Lim, Kyunggu Lee, Hyun Min Ahn and Yeonju Lee.

The quad were intrinsically linked together in one form or another nearly throughout the entire piece - but not like the pas de quatre in Swan Lake where the dancers move as one unit, or the rapid-fire steps that are passed from one performer to the other in continuation, as seen in the final lineup of Irish dance shows such as Lord of the Dance - their moments were more like individual parts of a machine working together in tandem to make it function. Their movements were sometimes synchronized, sometimes contradictory with one another but always chained together and informing each other. This brilliant, cutting-edge gestural design by co-choreographers and directors Jinho Lim and Kyungmin Ji presented another form of dance vocabulary equally as striking, unique and new as the previous piece, though entirely different in both intention and execution.

The sense of being 'linked' served as a clear metaphor for the shared condition of the female of the species. Though each had their individualistic moments, they were tied to one another. They began as rambunctious, childlike schoolgirls chanting songs in monotone and provoking the audience into small fits of laughter with their bone-dry facial expressions and playfully sexual gestures. There is a nice nod to the K-Pop as well as K-Horror genres when the schoolgirls morph into idol stars (in addition to their dance ability, they sing and rap quite well) then transition from that spotlight-seeking status to faceless entities with their long locks draped over their visages and their heads or bodies stuck into black boxes, exploring the darker side of gender oppression, even speaking (in English) about a woman as a widow needing to become 'invisible' where a man in the same position essentially gets a new lease on life. This, along with the allusions to the knife as a means of both protecting oneself, one's chastity and to be used for committing suicide, was evocative of the (thankfully) now outlawed Indian practice of suttee (or sati in Sanskrit) meaning "chaste wife" or "good woman", where a widow would throw herself on her husband's funeral pyre and die with his burning corpse.

Goblin Party utilizes modern and provocative interpretations of feminism, symbolism, metaphor and pop culture references with truly inventive movement and razor-sharp wit.

The third and final feature was a new take on an iconic and renowned work, Pollen Revolution, choreographed and originally enacted by the legendary Butoh performer with a foundation in modern, contemporary, classical dance and Eurythmy - Akira Kasai - who toured the world with the multi-dimensional solo work between 2001 and 2005. Kasai now brings it back to Japan Society (where he premiered the work in 2002 as his New York debut), but since has passed the torch to his son, Mitsutake Kasai, to present the piece and infuse it with his own worldview that incorporates many different dance styles and influences, not unlike his father.

So despite the fact this particular work wasn't created or conceived within the past few years, the interpretation has remained timeless, relevant and still of-the-moment to keep up with the other imaginative contemporary expressions.

Pollen Revolution commences with Kasai appearing onstage under bright lights and white walls, gloriously adorned in a richly embroidered kimono, white makeup, a jet black wig and majestic headpiece as an onnagata - a male kabuki actor who plays female roles. He performs a traditional, improvised dance that is utterly transfixing - a moving meditation. The performance and attire are resplendent with elegance and regal formality befitting the Genroku era (1688-1704), regarded as the Golden Age of the Edo period that also correlated to the time when kabuki and other arts thrived. The viewer is transported to the long gone phase in history by Kasai's controlled, doll-like movements, his subtle, delicate hand gestures and feminine, circular movements that were complimented by the authentic sounds of the strong male vocal intonations, percussive strikes, sharp flutes and gentle plucking of the koto strings. The stark lighting is a signature of kabuki (and has been used for Noh and Butoh as well) as is men portraying female characters (though kabuki was originated by Izumo no Okuni, a woman, in 1603), so much so that the brightly lit, all male en pointe company "en travesti"- Les Ballets Trockadero De Monte Carlo - have found extraordinary and unexpected success in Japan.

But as the lights shift, so does the mood and the movement. An eerie green glow is cast across the stage with swirling video gobo projections like a ghostly figure entrancing the dancer and informing the motions in contrast to the delicacy of the traditional figure. These transitions into the green haze occur on a few occasions, and each time they bleed a bit more into the other side, making the dance more frenetic, even stumbling, less graceful and more chaotic with the furious koto playing heightening the tension. When a crescendo is reached Kasai rips off the adornments as if being unraveled and coming undone, then the music and motion stop abruptly as stagehands enter like ladies-in-waiting, and relieve Kasai of the garments that are exchanged for a simple black top and trousers.

Once outfitted, he drops dramatically into a shard of white light sandwiched between black frames. (Lighting designer Michino Ono created such a purposeful and potent palette of color and light that it acted as such a crucial part of Pollen Revolution - it was practically another dancer on stage.) The sharply contrasting white face against the black clothing and Kasai's exaggerated facial expressions - from wry and mischievous to gaping-mouthed terror are reminiscent of mime and called to mind David Bowie's specific and unique exploration and interest in that art form (as well as his deep connection to and influences from Japanese art and fashion). The movements draw from all of those sources and he appears at times puppeteered or pulled by some internal force or impetus while discordant piano keys struck hard alternate with droning electronic music that creates the mood of an alien soundscape or heavy synth with a 1980s vibe, all of which articulated the dance.

One cannot be sure if the choreography was rigid and specific or more of a frame and the younger Kasai was given room to breathe for improvisation, but it certainly appeared to be the latter. Regardless, one thing was clear: Once he shed the traditional garments and formalities, he consumed the entire space of the stage in a way that was utterly free.

Butoh is unique in that it does not have a set vocabulary in the way that ballet does, so it makes sense that an artist would draw on many different forms of theater and dance; it is also notable that in Butoh, everybody's and each bodies' expression is completely unique and individual based not only on their training but on who they are as people (the internal world matters as much or more as the external), so Mitsutake's representation of Pollen Revolution would naturally be vastly different from his father Akira's original interpretation.

Kasai disappears offstage for a moment and returns in a striking, all-white slim suit under a powerful spotlight. While the angelic, liquid music and untarnished hue might seem to represent purity, calm or the heavenly realms, in Japan, white is the shade of death and the color choice here was symbolically more foreboding. A voiceover tells the tale of a lord who had a goblet of gold from which he drank his wine and tears over his lost mistress; he knew that the gilded cup was connected to his mortality and the moment he'd drink his last. The storytelling element was a refreshing twist in a performance that was impossible to predict and continued to surprise - for Pollen Revolution finished with a cascade of gold glitter raining on Kasai while he pranced around the space dancing in an entirely different form than before - large, sweeping motions of the hands and arms and even some spirited headbanging, all to a modern hip-hop anthem. But like death itself, it ended in complete silence.

The three performances presented by Japan Society's Contemporary Dance Festival: Japan + East Asia were so much more than a mere showcase of talent or a festival of what's current in contemporary dance in Asi. They were the painstakingly hand-selected demonstrations of revolutionary creative minds and bodies who are in tandem at the top of their games and just getting started. They are exemplary examples of a new way to approach, present and view contemporary dance.

North American premier of "Kids" by Kuan-Hsiang Liu with light and Wan-Lun Yu. Photo by Julie Lemberger.

North American premier of "Kids" by Kuan-Hsiang Liu with light and Wan-Lun Yu. Photo by Julie Lemberger.

North American premier of "Kids" by Kuan-Hsiang Liu from left is Kuan-Hsiang Liu (facing), Wan-Lun Yu, Yu-Yuan Huang. Photo by Julie Lemberger.

North American premiere of "Silver Knife" choreographers Jinho Lim, Kyungmin Ji (Goblin Party) from left are from left are Sungeun Lim (green shirt), Kyunggu Lee (white shirt), Hyun Min Ahn (pink shirt), Yeonju Lee (maroon turtle neck). Photo by Julie Lemberger.

North American premiere of "Silver Knife" choreographers Jinho Lim, Kyungmin Ji (Goblin Party) Hyun Min Ahn (at right) and Sungeun Lim, Kyunggu Lee, Yeonju Lee. Photo by Julie Lemberger.

Akira Kasai's "Pollen Revolution" performed by Mitsutake Kasai. Photo by Julie Lemberger.

Akira Kasai's "Pollen Revolution" performed by Mitsutake Kasai. Photo by Julie Lemberger.

Reader Reviews

Videos