BWW Dance Review: New York City Ballet Presents a Stunning Leotard Evening

New York City Ballet's performance on April 26, 2018, offered dancing with the vigor and bracing musicality that we have come to expect in an all Balanchine evening. As in almost all things Balanchine, high quality artistry can be provided when mind and flesh fuse, especially in the "leotard" ballets that Balanchine introduced from the late 1940s through the 1970s: no costumes or scenery, just dance and light. We can see the ballet whole, as it were.

While Balanchine has always been accused of choreographing great parts for women, here it is more of a draw. Balanchine perceived women through his own prism, while men were consigned to a somewhat lower level. Here they are sharing equally; Balanchine could create on men just as easily as women. It just was not trumpeted from on high.

"Concerto Barocco" is one of those ballets that bear constant viewing. Every time I see it, I am amazed at all the detail I re-discover in a performance--they are inexhaustible, from a flexed foot to a simple lift. The curtain rises in silence, the orchestra commences and on the first note, almost of out nowhere, the eight corps women are launched into what amounts to 20 minutes of non-stop dancing. They are soon joined by the lead female dancer and a soloist. In the second movement the soloist leaves the stage, to appear only briefly, while a male dancer enters to partner the ballerina in a seamless, controlled dance of quiet, controlled rapture. There are no histrionics; they move as though in controlled, structured measures, the corps surrounding them, and then parting, then forming statue like positions. The man leaves, the second soloist returns and the women dance quickly, as if they were on a shot of classical music adrenaline. There is humor in this last movement; it looks like Balanchine mixing classical movement with twentieth century jazz inflected steps. Once they are finished, the curtain falls. And that's it. No narrative-- as in most Balanchine ballets, just sheer billowing movement.

Maria Kowroski as the ballerina and Abi Stafford as the soloist both offered first-class performances, especially Kowrowski, whose beautiful line and seemingly inexhaustible energy never flagged. Abi Stafford offered whirlwind energy and a smiling countenance that was up to the demands of a part that, if not exceeding those imposed on the ballerina, required strong, commanding technique. Russel Janzen offered solid support in squiring and lifting Ms. Kowroski. As for the eight ballerinas in the corps, they kept up with aplomb, probably the only word I can find, because their movement never ceases. One can imagine it continuing long after the performance has finished.

"Agon" (1957) Balanchine's twentieth century masterpiece came next, a ballet pitting bone against bone, mind against mind. Dancers performed physical feats that could not have been imagined before. As cerebral as it is, the ballet still defies logic to a point: How can a woman fly like that? How do dancers dance without a beat? Won't their muscles collapse? They never do, but it only appears so. The humor, the swagger and seeming nonchalance are like smoke screens, masking the physical intensity onstage.

New York City Ballet commissioned the score from Igor Stravinsky, marking his final collaboration with Balanchine. This was their watershed. Sixty years after its premiere, it has never left the repertoire. Nor will it ever!

The big disappointment of the performance was the central pas de deux, here danced by Teresa Reichlen and Chase Finley. Reuchlin is very tall and judging by that alone, would be a natural fit. But her technique is what I call gooey. It looks strong, yet it's basically soft, its center lacking gravitas. She exerts too much and doesn't have the clean finish that is needed for the final collapse onto her partner's shoulders. Finlay lacks personality. True, the part does not call for characterization, but he seems almost neutral--there is no hunger in his dance. You need a fighter, a contender. Don't attempt "Agon" if you are deficient in those areas. It will defeat you every time.

Anthony Huxley, Ashley Laracey and Lauren King performed the first pas de trois, aloof, yet playful, Savannah Lowery was in good cocky form in the second pas de trois, ably supported by Daniel Applebaum and Joseph Gordon.

"The Four Temperaments" closed the evening, and a better danced performance would have been hard to find. In the third theme, Miriam Miller was exceptional. Tall, physically alive to the music, concentrated, with beautiful feet, she looks like a real ballerina in the making. I hope to see more of her in the future.

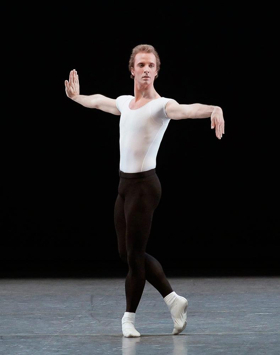

Sean Suozzi in Melancholic, Sara Mearns and Jared Angle in Sanguinic, Ask la Cour in Phlegmatic and Megan LeCrone in Choleric, pointed up the very qualities that Balanchine had always sought: dance, don't push, follow the music, don't lead and, in my own words, cast a spell on the audience, one that shows them why dance is important to their lives, how it can animate us, yet at the same time calm us. It is an art form unlike any other. And it still is.

New York City Ballet has seemed to me a company in flux since Balanchine's death in 1983. There were so many outcries of poor dancing, new stale repertoire-you name it. And the latest with the overthrow of the Peter Martins regime, knives were drawn. Still, not all has been bad, nor do I think it ever was. In the last few years Justin Peck, Alexander Ratmansky and Christopher Wheeldon have been providing the company with works that might signal a new breakthrough in City Ballet's branding. Maybe it just won't be a George Balanchine-Jerome Robbins kingdom. More later.

Photograph: Ask la Cour in The Four Temperaments.

© Paul Kolnik.

Reader Reviews

Videos