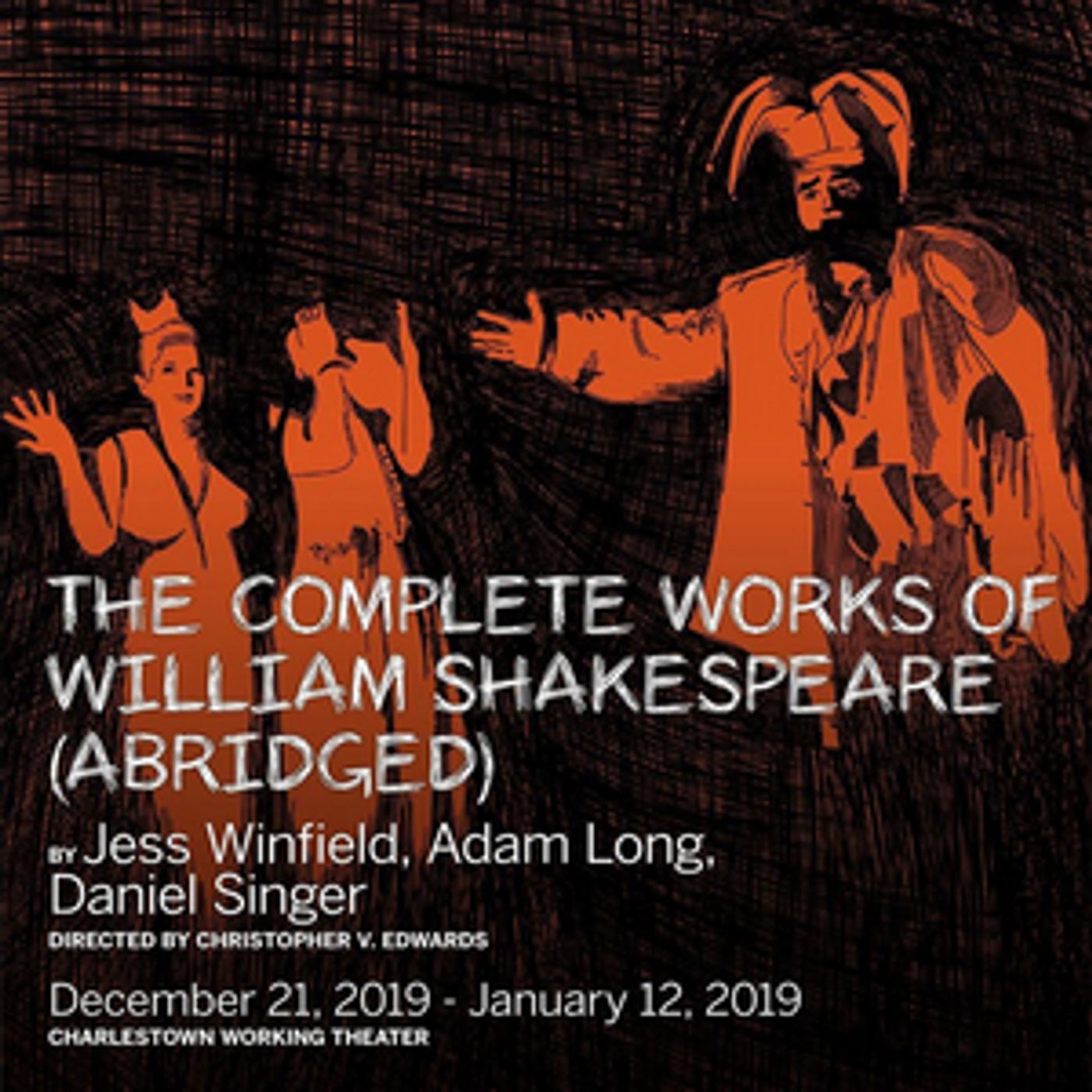

Review: THE COMPLETE WORKS OF WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE (ABRIDGED) at Actors' Shakespeare Project

In a recent review for Actors' Shakespeare Project's King Lear, I tried to boil down what an audience can expect from any piece the group presents. (Thanks to their conveniently affordable student tickets, they are a theatre from whom I have perhaps seen more productions than any other company.) I previously wrote that three of their dominant tenets seem to be; "deeply human connections on stage, a clear commitment to narrative, and a genuine sense of gratitude for coming to be present as their tale unfolds." Upon seeing The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (Abridged), all three statements remain consistently applicable. However, I unfortunately felt the pang of a fourth major tenet that routinely plagues ASP's work, namely, an outdated understanding of gender performance. Using the word "outdated" to refer to anything done by a theatre that regularly presents plays written nearly 500 years ago may seem imprudent, but I feel the word exactly addresses the issue.

It feels necessary to note that, even in a westernized world, the Elizabethans with whom Shakespeare hobnobbed would have had a different concept of gender than the binary we now enforce. But it is this very strict, modern binary that ASP has once again leaned heavily upon for various punchlines to their jokes. A male actor playing Juliet's nurse enters weeping with false breasts akimbo, a crossdressing woman feigns to have a penis, a female actor enters with a gruff, deep voice as a mustachioed Claudius. In response to all of these abominations to our stringent societal pact with the binary of our own invention, the majorly old, white audience immediately bursts out in laughter. Does this matter? Yes. As many artists fight for the right to express their gender in this country, this laughter at the expense of queerness can be incredibly harmful and indicative of underlying prejudices. While ASP is by no means the single offender of these ignorances in Boston's theatre scene, their reduced casting practices and interaction with works that call for cross-dressing elevate the need for them to be better. While I hope to continue engaging with their works this season (I'm particularly excited for Igor Golyak's Merchant of Venice and Rebecca Bradshaw's Henry V) I will certainly be anxious to see how they will engage with growth in this direction.

Ironically, director Christopher V Edwards refers to this 1988 comedy as a quasi-"period piece" in his director's note, referencing how dated some of the jokes are. Much of the gendered humor in the script feels dated, but perhaps no more dated than the references to Citizen Kane or Titanic that fail to earn even sympathetic laughter from the audience. (Although, the age of the jokes may be less at fault than the framing, as an Arianna Grande reference also lands to the sounds of crickets.) Let's face it, the idea of three actors spending a few hours going through parodying versions of Shakespeare's plays sounds like it has a lot of potential to be funny. But it is not until the eleventh hour, really, that the script gives us the costume-switching, sword-wielding, super-speed Hamlet that the show's title prepares us for.

Until that point, we sit through long-extended jokes, cheap pop culture references, and even an extremely long harmonica solo. Though the actors have mined the script for everything it is worth, there is too much dead space written between the formulated punch lines. The piece begins with a more or less formal lecture about Shakespeare and we meet Marc, Ivy, and Rachel (all actors using their real names). An issue arises as, unlike in backstage farces like Noises Off! or The Play That Goes Wrong, these actors are not playing lovable, silly stereotypes. Instead, they play slightly exaggerated versions of themselves, but, in reciting the scripted jabs at the audience, the trio is decidedly un-charming. The whole concept of the show can't decide on the intelligence of these three fictional actors. Sometimes they are correcting the audience's perceptions of classic English literature and sharing historical information, and the next moment one of them thinks Othello was a moor to which ships could be docked. It is only in the extended sequences in which we see the trio commit to sketch-comedy characters that they excel.

Marc Pierre is riotous as a stereotypical New Yorker, a Keanu-Reeves-esque Romeo, and an excessively Scottish witch. His character work is physically transformative and he exudes a charisma and confidence that sets the audience at ease. Rachel Belleman steals every scene she is in, whether as the handless child, Lavinia, the overly Scottish MacDuff, King Hamlet's ghost, or any number of puking tragic heroines. Belleman holds the distinction of being an inescapably funny performer, who, with a single shriek or gesture, is able to win the audience over. Early on, she wins our affections and keeps us in stitches until her final bow. Unfortunately, these two have soaked up the lion's share of the memorable character work, and Ivy Ryan, whose 'Ivy' character is the most uppity and least lovable of the three, is left with a series of interchangeable and forgettable roles. I was waiting for her to have a go at a role as well-developed as Belleman's Ophelia or Pierre's Polonius, but neither her Hamlet nor her Titus Andronicus seemed to wander so far into absurdity. (Because I have seen her perform before, I feel confident that it was her assignment to an unsatisfying role and not her talent that made her track seem lackluster.) As a troupe, the three have fun conducting audience participation, creating live music, and engaging in a loving parody of performance art.

Edward's director's note explains that, in producing The Complete Works, the company's hope was "getting people into a room, breathing the same air, and laughing together." Upon entering, the odds are immediately stacked against the cast in their quest for general merriment, as Elizabeth Cahill's sound design cycles through redundant covers of The Bee Gees' 'Stayin' Alive' and stage hands sporadically adjust Afsoon Pajoufar's eye sore of a set. (With a small, technically simple piece like this, I wouldn't normally allot space in the review to discuss the set, but the random assortment of visual stimuli in the space detracted from the overall experience so greatly that I feel it must be mentioned. Pulsating lights reflected off of gold mylar streamers and a trio of bright orange tarps hung limply on the stage. The tarps were not only unattractive, but detrimental. In a piece that relies heavily on moments of crisp, clean entrances with quick visual gags, the incessantly shifting swathes of orange revealed jokes before their punchlines had been set up, and noisily crinkled, exposing too early where each actor was about to appear. Overall, this was not a well-developed design, and the piece would improve greatly were it performed in an unencumbered black box.)

This was a surprising piece for ASP to tackle, and evidently an attempt from a new artistic director to expand audience appeal (although, I question how enjoyable this performance would be for anyone unfamiliar with Shakespeare's canon). However, I would have had a more enjoyable evening had this cast launched a zany version of one of the Bard's comedies directed by Edwards or developed their own parody of his works. This clever (I will concede that it is clever) fringe festival piece has far and above run its course, and I believe it is time for companies to stop producing it.

The performance runs through January 12. More information here.

Reader Reviews

Videos