Review: DETROIT RED at ArtsEmerson

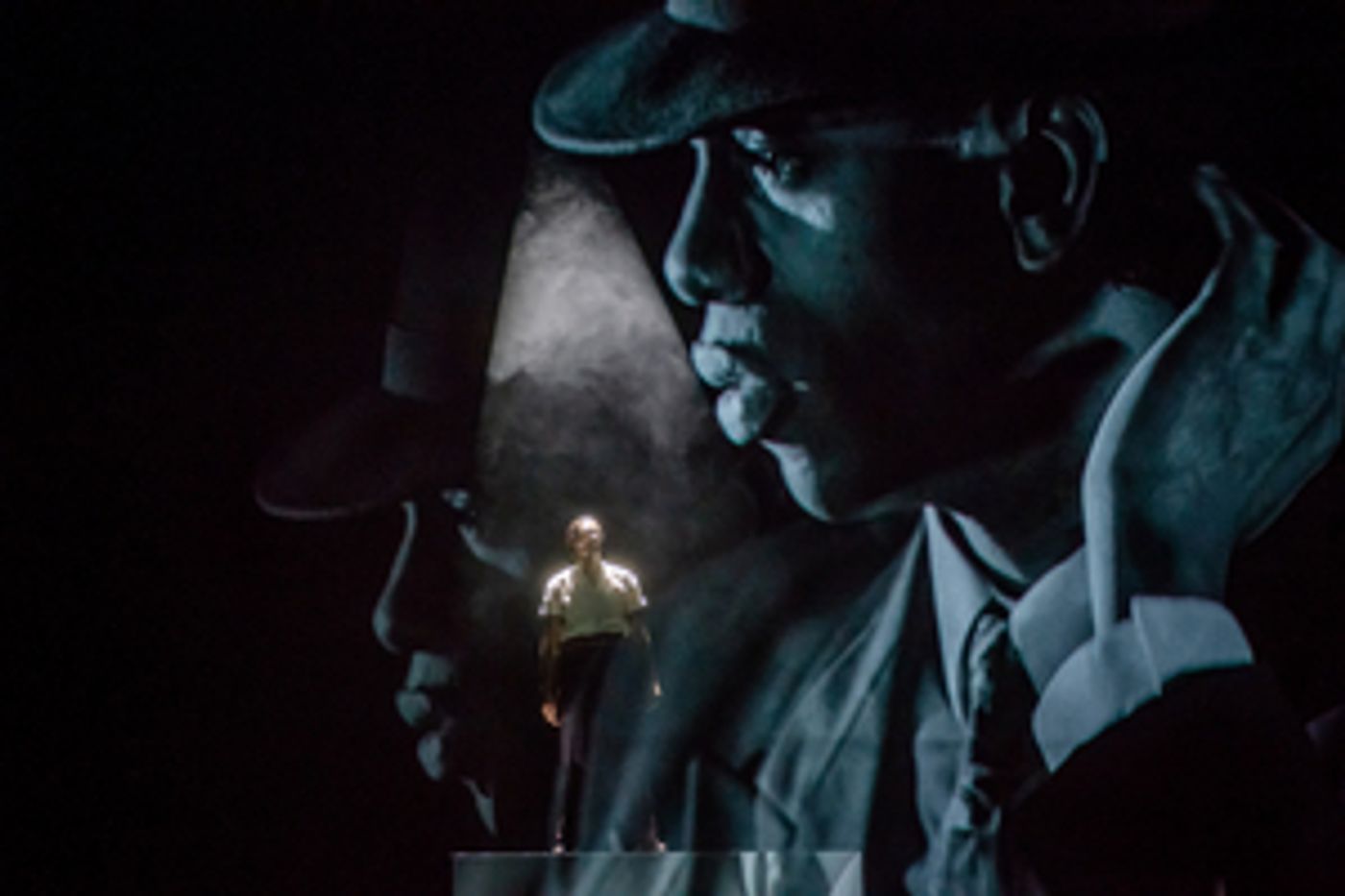

In David Mamet's book On Directing Film, he breaks down the way a linear narrative can be conveyed by placing images in direct contrast to each other. "The dream and the film are the juxtaposition of images in order to answer a question." Certainly, with a majority of the action taking place upstage of a scrim and the fusion of filmed and live material, ArtsEmerson's Detroit Red, an original play by Will Power about Malcolm X's early adult life in Roxbury, leaves one feeling more as though one has watched a movie or woken from a dream than sat through a performance. Recently, I also saw Gloria: A Life, which is playing at The American Repertory Theatre. While I admittedly found the show to be trite and pandering, it obtusely fused projection effects with live performance in a way that felt cheap, gimmicky, and more like a new SnapChat filter than anything else. Contrast that with Ari Herzig's film work for Detroit Red, which snaps the audience effectively between viewpoints in black and white and splays broad images across the haziness of Adam Rigg's nondescript set. The success of the production lies in the success of the filmed elements, which establish a framing device, pinpointing the action to an exact moment in time. Additionally, the projections act as effective abstractions, allowing the actors to waver between realism and poetry as photos of their faces appear as oversized watermarks in space. Lighting designer Alan Edwards equally contributes to the cinematic feel of the piece. Sharp shafts of light slice through open space and act, ingeniously, as the camera lens might in film, focusing our attention on specifics and the relevant details. Aside from a few extraneous hat changes for the three actors who take on all the roles in the piece, between the work of Herzig, Rigg, and Edwards, the performance seems to be a study in the logistics of jump-cuts or cross-fades in real time.

Adding to the film-instead-of-theatre feeling in the space, the performance actively roused and engaged the audience, which had a huge swathe of Boston school groups present. The crowd felt comfortable verbalizing responses, in part, because of our physical separation from the action presented to us, and to be able to laugh, cheer, gasp, and grimace in solidarity with those around you is a rare treat.

Will Power is carefully cavalier with his language, to an extent some might call irreverent. (Anyone unfamiliar with his work should listen to the soundtrack to Steel Hammer on Spotify, his theatricalization of John Henry legends in collaboration with Anne Bogart and Julia Wolfe. It is strange, beautiful, and dreamlike in a wholly different way from Detroit Red.) He has written a script that does not shy away from the realities of Malcolm Little before he was Malcolm X, fully engaging with his background as a pimp, sex worker, shoplifter, dealer, abuser, and more. The text calls for the exact treatment ArtsEmerson has provided, treading through dialogue with familiarity before spinning off into rivulets of spoken word poetry that seem as smart as (if as tangential as) a Colson Whitehead novel. I was relieved that, despite some of the dramaturgical work in the program, the piece itself did not set up Malcolm Little as a man in need of saving. We are lead through moral ambiguity with our flawed hero as he navigates the options for a Black man living in Roxbury, rather than seeing a protagonist who must be rescued by the system in order to achieve greatness. The piece holds a lot of geographical interest for locals, especially those who may have engaged with some other great works about Blackness in Boston this season, like Company One's Greater Good by Kirsten Greenidge, Fort Point Theatre Channel's workshop of Roslindale Love Canal: A True Story of Survival by Ashley-Rose, or TC Squared Theatre Company's Smoked Oysters by Mary McCullough. Ultimately, I question if the piece will work outside of Boston, as the narrative is not as strong or engaging as the language itself. Additionally, the script falls into the traps of biographical works which seek to be heartwarming or overly uplifting. I couldn't help but think of the more unbearable moments in Bohemian Rhapsody or Dolemite is my Name as Malcolm was told by a sage, kindly, homeless man that he has 'a lot to say' and is encouraged to share some of his ideas with people (wink, wink). I don't necessarily think that, in retelling the stories of people's lives, we always need to see such a literal epiphany which eventually leads to their life's significant work. Especially in this piece, which does not cover Malcolm's life after his first arrest, the scene feels bombastically rosy and out of place.

As Malcolm, Eric Berryman is efficaciously charismatic. Despite his rogue temper and roughness, his interpretation is sympathetic, engaging the crowd through lengths of poetry in ways which would leave the most refined Shakespearean actors scrambling for a pad and pen. The script favors him, casting the other two actors in various supporting roles, but he favors the script right back, imbuing it with a constant physical tension that keeps us in suspense, even when a lack of events might invite us to let the piece pass by glazed-over eyes. Brontë England-Nelson takes on all the white character roles, from blonde socialites with a preference for Black men to wealthy businessmen committed to loveless marriages while firmly planted in the closet. England-Nelson made me think of Kate McKinnon on SNL, she can change her wigs and costumes all she wants, but every role is ultimately the same. Neither actor is unpleasant to watch, in fact I think McKinnon can be very funny and I really liked how England-Nelson rhythmically approached the script. However, in a piece that showcases dexterity and ability to shift incessantly between characters, neither will excel.

The most captivating scene in the show is the climax between Malcolm and his wealthy employer, who makes sexual advances on his staff. It is violent, vulnerable, and, even in an expansive space, feels cramped and stuffy. The script does not dawdle with coming down from the rising action, abruptly ending the piece after a concise reflection on the preceding events. When the stage went dark, the audience sat in stunned silence for nearly thirty seconds before applauding. Again, it is a rare treat to feel as though you've taken a journey with those around you.

Director Lee Sunday Evans has crafted one of those rare gems in which her artistry, which would certainly peek through in any present flaws, seems almost imperceptible. I was very lucky to catch her production of Dance Nation by Clare Barron at Steppenwolf before it closed, as, without the use of scrim, haze, or projection, she crafted a similarly cinematic reality. It is evident that she has a firm grasp on the possibilities of modern technology and the ways it can shape theatre, but, perhaps more importantly, the way it has shaped audiences. Not just because of the success of Dance Nation, I think hers will be a name to watch out for in the coming decade as a leader who is making work that audiences want to engage with.

Detroit Red plays at the Emerson Paramount Center until February 16. More info here.

Reader Reviews

Videos