Interview: Dayenne CB Walters of LONG DAY'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT at WaltersWest Project

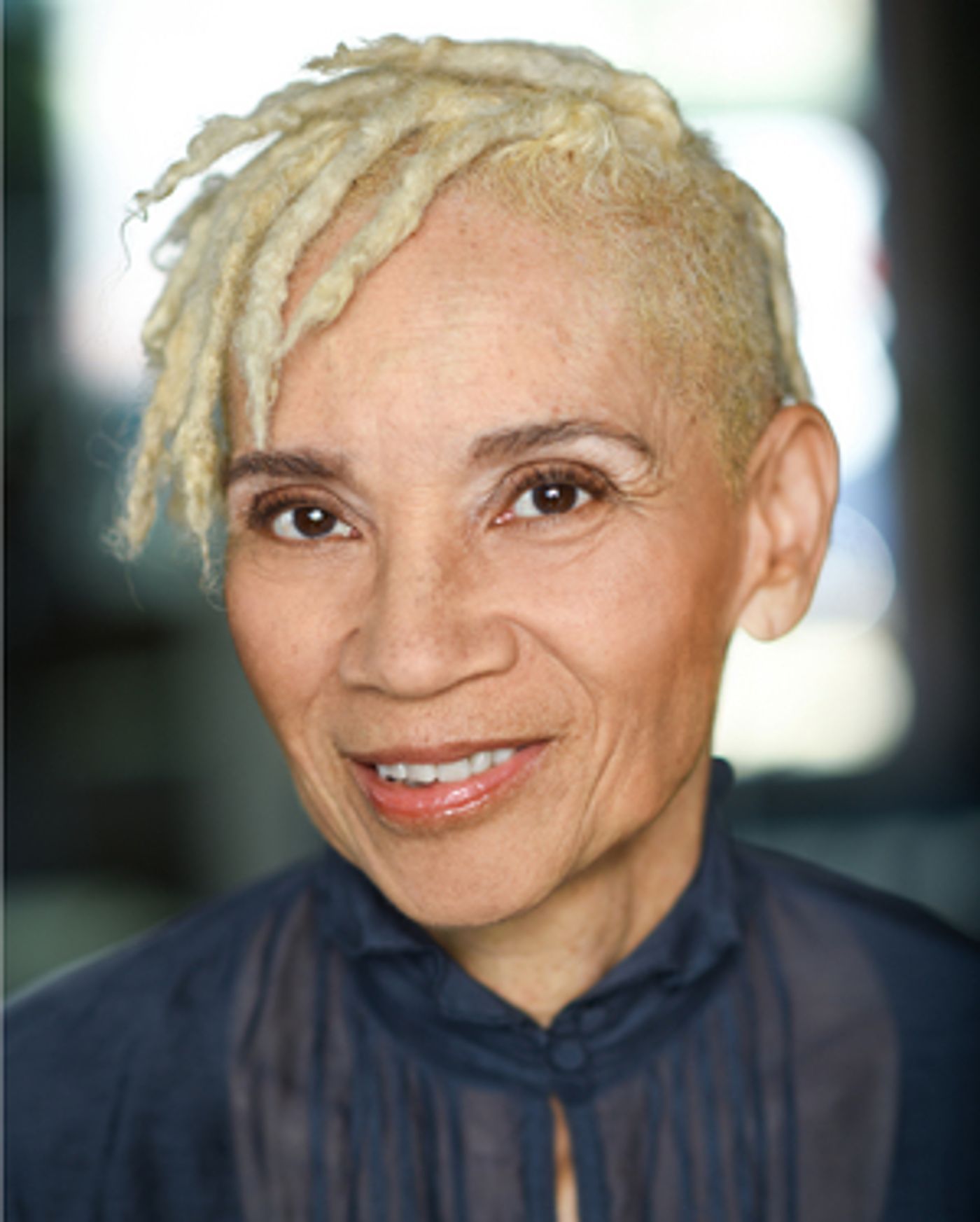

After months of Zoom interactions and digital programming, I would be lying if I said I was excited by the prospect of a 3 hour Zoom reading of a dreary, 1941 Eugene O'Neill play. However, if there were an equivalent antidote to my hesitations, it would be in the impressive billing "Directed for Zoom by Audrey Seraphin" (whose recent Coriolanus for Praxis Stage was viscerally violent and decidedly not-boring or dreary) and featuring a veritable if intimidating list of a few of Boston's best actors: Dayenne CB Walters (who was recently haunting and strange in The Crucible with Bedlam Theatre), Paul Benford-Bruce (indelible earlier this season in Smoked Oysters with TC Squared), Zair Silva (potent as the titular role in Coriolanus), Dominic Carter (who stole the show despite limited stage time in Fences at Umbrella Stage Company), and familiar face, the palpably genial Ciera-Sade Wade as Cathleen.

For just $10, audiences can stream the reading of Long Day's Journey Into Night until Friday, June 26 here.

While the virtual format limits the capabilities of traditional theatre design, the team has done a noble job of curating a cohesive, turn-of-the-century aesthetic behind them as an evocation of the living room in the Tyrone family's summer home. Though the text takes a poetic, semi-autobiographical, scathing look at O'Neill's Irish-American family, anyone familiar with the names of the cast listed above may note that this might not be the Tyrone family as we imagined them in an Introduction to American Drama. To establish the visual world of the historically-viable, dramaturgically-supported reimagining of the Tyrones as a Black family, the reading opens with an overture featuring photographs from the William Bullard Photography collection at the Worcester Art Museum. Bullard's public domain photographs give us a glimpse of the little-discussed realities of Worcester's flourishing Black community at the dawn of the 20th century. We see images of middle class and wealthy Black people sitting solemnly in formal attire or smiling with a child on their lap.

Read more about the Bullard collection and a 2018 exhibition of the photos here.

I was thrilled to be able to chat with Dayenne CB Walters, who, with her impressive smattering of acting and directing credits, acted as co-producer as well as performer in this piece.

"I wanted to challenge the type of inclusivity there is in Boston theatre in general. So I spoke to Amy West (who acted as co-producer and directed the live production) about my desire to do this role-- Mary Tyrone. I've been given the role many times in scene study and have realized it not only speaks to me as an actress but as a woman and as a Black woman. I was stunned by similarities between O'Neill's Irish-American family and my own family." Citing the script's insightful exploration of the playwright's family through references to cultural stereotypes and unreliable perspectives, Walters wanted to invite audiences into the conversation about how this might reflect a relationship with our own families. She moved quickly. Aided by the financial support from Fort Point Theatre Channel and the performance venue set at Hibernian Hall (whose history boasts an inclusive, and uniquely-accessible audience base), the production began to come together.

For Walters, her new producer hat was not about wanting to maintain control, but rather wanting to sidestep needing to ask for permission. "This project wouldn't neatly fit into any of the niches I'm really familiar with in Boston theatre. Black actors are still discussing permission. How is permission granted? Who gives out the permission? I realized there is really no permission needed throughout this process." She explains how, based on dramaturgical work researched by Michael Anderson, Ciera-Sade Wade, and the cast, the historical reality of a Black Tyrone family is entirely viable. "I really dove into the dramaturgical work. We all wanted to be real about it. So we looked at Black history, and there have always been Black actors who have excelled in performing Shakespeare." She elaborates on how research into the Oak Bluffs community on Martha's Vineyard, which had a significant draw in the 19th century for people of West-African descent, as well as the widespread reliance on medical morphine across class and racial divides suggested that a Black Mary Tyrone is entirely believable.

Early discussions with the cast saw them confronting ideas that audiences may have raised upon seeing this production. Was this a "color-blind" world in which a team of Black actors was playing a white, Irish-American family? "This is absolutely not a 'color-blind' production," she affirms. "We approached everything from the understanding that the Tyrones are a Black family. All of the assumptions and details of the story- a Black family, in the United States, in 1912, a Black woman married to a Black actor, living in a nice summer house. This is a Black family. Maybe this is not every Black family, but no plays written about Black families are about all Black families."

She relays a question that came up in discussions with the actors, "What makes a Black play?" and shares how some actors felt that Richard Wright's canonical novel, Native Son, actually reflects their own family history less significantly than Long Day's Journey Into Night. "This is not a happy family, but it is a family that clings to each other in ways we could identify with. The experience with this script made all of us realize there is more to discover in the poetic language of this play."

Walters says that, without any concrete plans in place, the team hopes to be able to stage the production in a theatre one day. The reading is an excellent look at the potential poignancy of this idea that would certainly develop further with the original score commissioned for the production alongside songs, dances, and staged combat. Those unfamiliar with O'Neill's script could not have a more unpasteurized, contemporary glimpse of the turmoils within this foreboding work of American drama.

Videos