Review: A Wry Storyteller Narrates Horror and Recovery: THE HAPPIEST MAN ON EARTH at CATF

On stage through July 28th, 2024.

It’s good to be back in Shepherdstown, West Virginia again, reviewing this year’s offerings of the Contemporary American Theater Festival. I often remind my Baltimore readers it’s less than two hours’ drive from our town.

I covered the Festival annually for some years, until Covid. I caught the first reopened season in 2022, and then had to take a year off. It’s changed a bit since my last time. There’s a new Producing Artistic Director, Peggy McKowen, who has succeeded founder Ed Herendeen, who had shaped the Festival from its inception. There will be a five-play schedule this year, rather than the pre-pandemic six. The schedule for auxiliary events has been shaken up. And the intriguing tendency of the Festival to cast actors in more than one of the shows has been jettisoned, surely simplifying the logistics (as well as the lives of the performers). Also, there is a new venue, the Shepherdstown Opera House, added to the three stages that the Festival has relied on in recent years.

What hasn’t changed is the variety and the professional quality of the shows. So let’s get down to them.

First up, at the aforementioned Opera House: The Happiest Man on Earth, an adaptation by prolific playwright Mark St. Germain of the 2020 autobiography of the same title by Holocaust survivor Eddie Jaku, né Abraham Salomon Jakubowicz (1920-2021). Significantly, Jaku, who emigrated to Australia in 1950, delivered his story repeatedly over the years in talks with visitors at the Sydney Jewish Museum. St. Germain’s play is in effect a rendering of one of those talks.

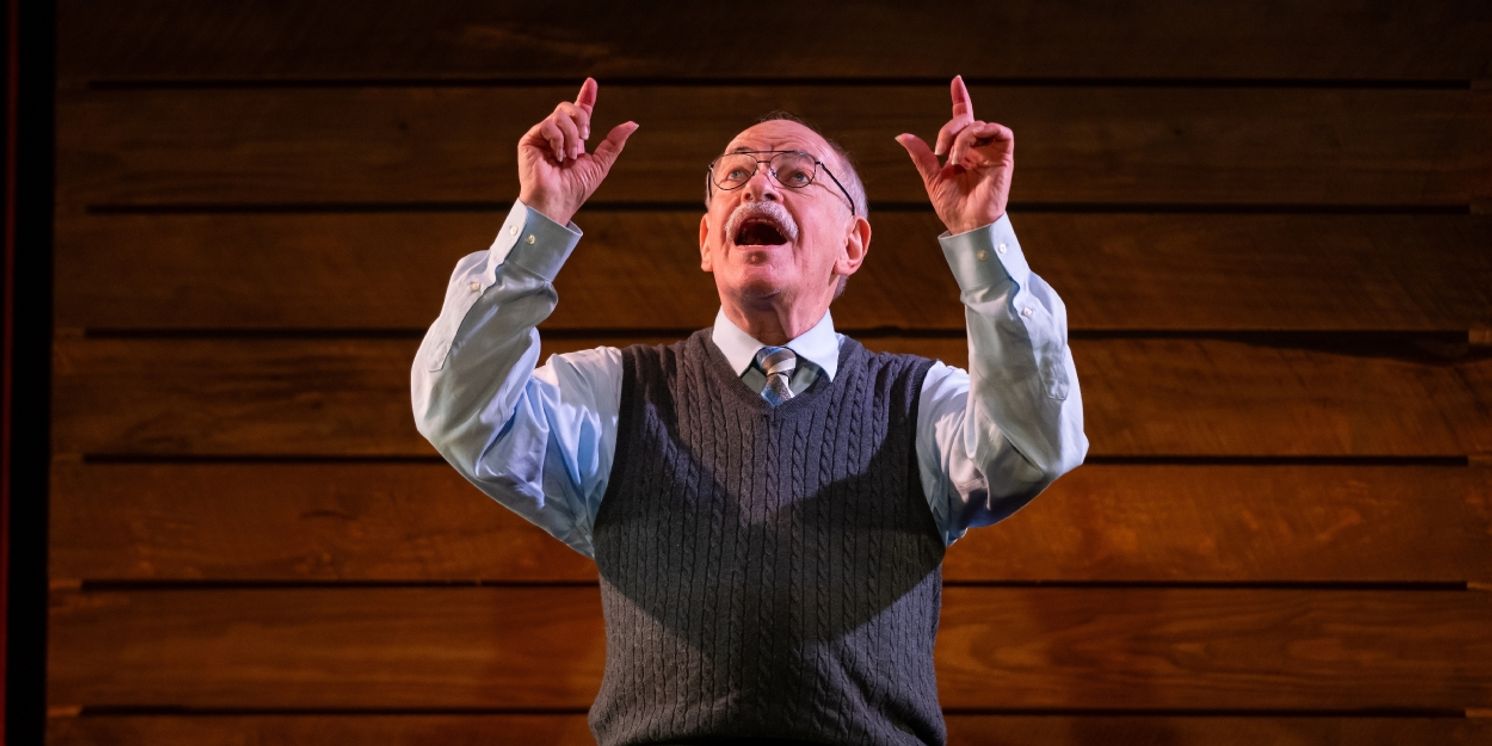

The framing is there from the first moment, as Jaku, portrayed by actor Kenneth Tigar, appears in the middle of the auditorium, chitchatting with members of the audience en route to the stage. By the time he arrives there, we have already learned much about him: he’s elderly, cheerful, engaging, wryly funny, and he speaks English with an accent suggesting Middle European origins. Soon we also know that this cheerful and engaging guy is nonetheless here to tell a grim story: how the Holocaust pulverized his family and early life.

It's not an unfamiliar tale, following Jaku from comfortable circumstances in a nurturing family through less-comfortable circumstances (being expelled from his school for being Jewish) and fighting to get an education, through being badly beaten by thugs on Kristallnacht while watching his ancestral house be torched, through efforts to escape the noose being gradually tightened throughout Europe, through separation from his parents, through Auschwitz and Buchenwald and starvation, punctuated by repeated efforts to escape, through being saved repeatedly by the kindness of others but also by blind circumstance. Because there has been a sizeable body of Holocaust literature, drama and cinema, little of this is exactly new to us. But Jaku’s personality, his wry way of describing these grim situations, makes us eager to hear them recounted.

For instance, here is Eddie, recounting how, after he has finally been rescued by the Americans and hospitalized, he grabs a nurse by the arm, demanding to know his prognosis. “Emma, I’m asking you. I won’t let you go until you tell me what the Doctor told you!” Emma’s reply: “Pretty feisty for a man who can’t brush his own teeth.” Eddie’s rejoinder: “Please. The truth. Will I live?” Emma: “The Doctor says you have cholera and typhoid. You’re malnourished, you weigh only 28 kilos. Your odds aren’t good.” Eddie’s reaction: “Thank you, God! I have odds!” This is a natural story-teller at work.

What holds the attention even more, however, are not the details of Jaku’s ordeal per se but the question of how he transitioned from the desperate, starving, distrustful and well-nigh dehumanized trauma victim the Holocaust had made of him to “the happiest man on earth,” his own phrase for who he became, the man we had begun to meet in those first moments of the play.

To the extent this play can be called a drama, this is the dramatic issue that needs resolving. There is a turning point, but not a facile one. Even after Jaku meets and marries a sort of relief worker, he is still in a post-traumatic frame of mind, always on the lookout for danger, skittish around crowds, closed-off. He understands that he is failing as a husband. But then there is an event that in retrospect, he says, was the instant “my heart was healed.” The last moments of the play recount the joyous and productive life that sprouted in that moment, a life driven by a desire to prosper in honor of the six million who died. He ends by in effect saying that part of the healing is the retelling of his story, an act that the elderly Jaku repeatedly enacted.

I said before that the story isn’t exactly new or news. But the retelling is important anyhow. I was privileged to hear a talk by survivor Martin Maxwell in 2018, three years before he died. Maxwell was a little older than Jaku, though the two died in the same year. Maxwell’s Holocaust experience was briefer, because he escaped to England and was able to fly gliders for the British army. At the end, however, he laid an emphasis on the same two points as Jaku: the importance of not merely surviving but spiritually prospering, and the importance of telling his story repeatedly.

In situations like this, listeners, Jewish and Gentile alike, benefit, I think especially because the empathy such accounts stimulate broadens our horizons, and makes us aware of our human kinship with all victims of mass killings, persecutions, war atrocities and the like, of which there seems to be an unending supply. Listening, for instance to Jaku recounting how, as the war drew to a close, the Nazis were marching their band of prisoners back and forth between American and Russian lines, seeking some way to escape, I could not help thinking of how this chimed with recent accounts of Gazan refugees finding no permanent abodes anywhere, and being kept constantly on the move by Israeli forces. Irrespective of either side’s justifications in the present conflict, while history is not repeating itself here, it is rhyming. There are a lot of rhymes out there. In honor of men like Jaku and Maxwell, we must keep our minds open to recognizing those rhymes from wherever they come.

The Shepherdstown Opera house, a former vaudeville house, art movie house, and now a reopened, more general venue, new to me, is a good fit for this show. Compact and narrow, with excellent acoustics, it works well for intimate shows like this one. Notwithstanding the simplicity of the house and of the script, the set, by James Noone, an assemblage of vertical slats whose interstices can be lit up, suggesting the settings or events being discussed, adds some interesting complexity to the retelling, as does the sound design by Brendan Aanes.

Of course, in the end the whole enterprise rests on the shoulders of Kenneth Tigar, who is now in at least his second stint as Jaku (after a production last year at the Barrington Stage in Pittsfield, MA). Over the whole process, he and the playwright and the director Ron Lagomarsino have been working in tandem. Tigar seems to disappear into the character. We are not conscious of acting, just of Eddie Jaku. The measure of Tigar’s achievement, and of the team’s, is just that simple.

You should meet Mr. Jaku.

And I'll review the Festival's other plays in subsequent posts.

The Happiest Man on Earth, by Mark St. Germain, directed by Ron Lagomarsino, produced by the Contemporary American Theater Festival, at The Shepherdstown Opera House, 131W. German Street, Shepherdstown, WV, through July 28. Tickets $70, $60 for seniors, available at https://catf.org/buy-tickets/#toggle-id-4, or at box office, boxoffice@catf.org. Adult themes and language.

Photo credit: Seth Freeman

Reader Reviews

Videos