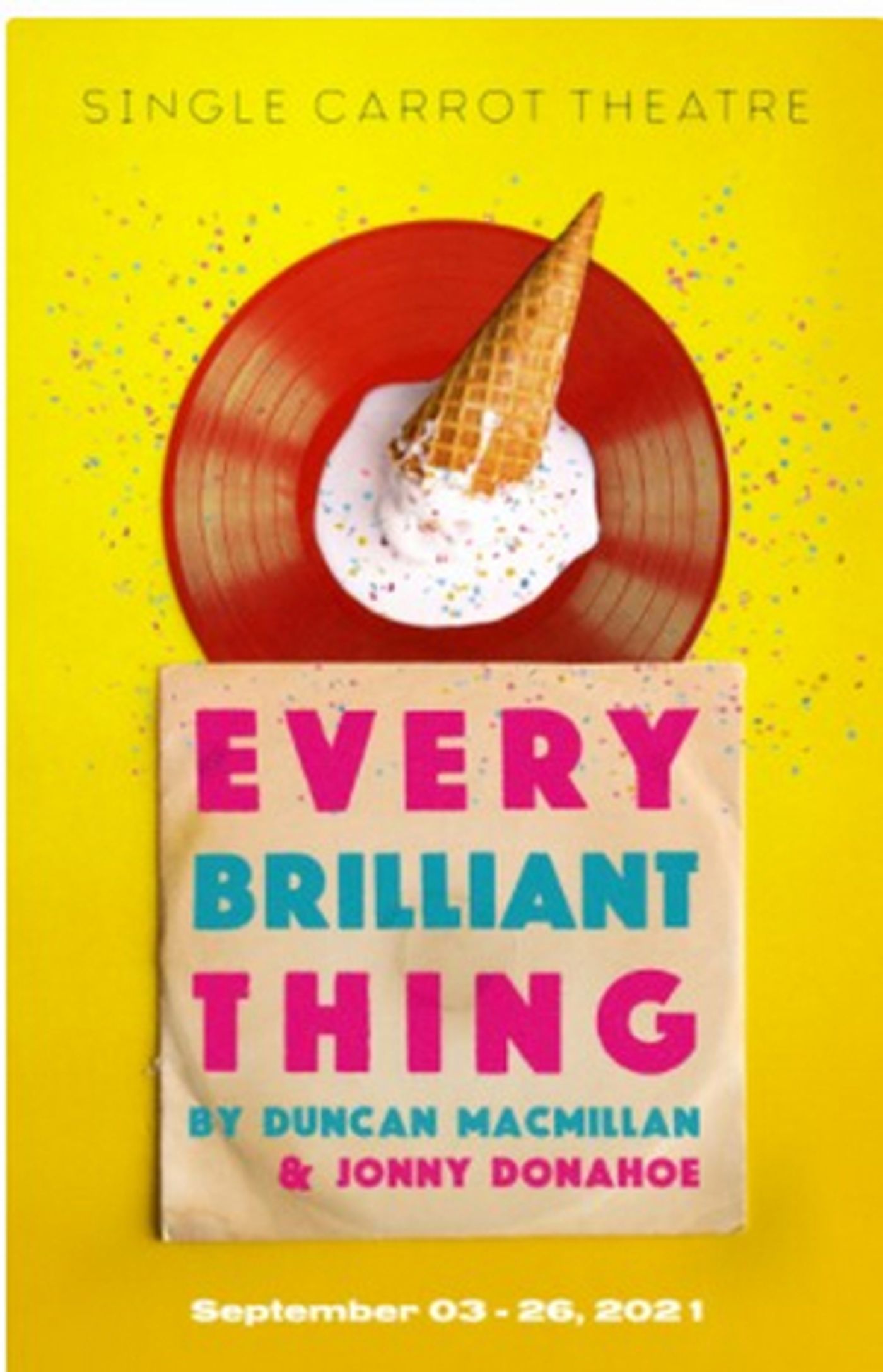

Review: Suicide Isn't Painless, But It Can Be Funny: EVERY BRILLIANT THING at Single Carrot Theatre

.

We don't generally think of suicide as a laughing matter, but Every Brilliant Thing demonstrates that, properly presented, it can manage to be called that. To merit the label, as the show, now presented by Single Carrot Theatre, demonstrates, you need to showcase an offsetting thing, a summary of the reasons to live: an evocation of all the thousands of things that make life, and hence the choice to live, worthwhile. The dialectic between the attraction these "brilliant things" exert and the lure of the exit to which depression beckons us is played out in the observations and experiences of the show's unnamed narrator.

Unnamed does not exactly mean anonymous. The original embodiment of the narrator was a specific person: Jonny Donahoe, a British comedian, who, working with noted playwright collaborator Duncan MacMillan, crafted this theater piece, and who then performed it (U.S. premiere 2015). It might have been thought that he was drawing on his own observations and experiences, the confessional kind of comedy that animates so much standup. His cagey comment to an interviewer, however, suggested otherwise: "It's inherently truthful of my life, and it's also true to [writer] Duncan MacMillan's, but none of the story happened to us. We say it's based on true and untrue stories. Whilst the narrator hasn't lived my story, there are a huge number of similarities, and that life has been lived by a number of people. We've met those people, we've talked to them, and we're trying to tell their story eloquently and as well as we possibly can." So this is actually not billed as any sole individual's biography at all, but more of an everyman's (and everywoman's) story. Evidently the suicidality of loved ones and the impact of that on those who love them are commonplace enough things that even a performer who has not experienced them personally can still give them voice.

Commonplace, and potentially laughing matters. With Donahoe's imprint on it, the performance comes across more as standup routine than play. The show draws liberally on a staple of standup: the impromptu enlistment of individual audience members with all of their bashfulness, unpreparedness, and reluctance, plus, to be sure, their inner improv artists, to become willy-nilly participants in the fun. And that enlistment works thematically with the sense that, even though the narrator is but one person with one specific story, the draftees from the audience speak for many of us. Thus, as the narrator orchestrates them for progressively more challenging feats of participation, the audience comes to identify with the project, and to identify with the tale the narrator tells.

That tale is of growing up in a family with a suicidal mother, and of the lasting impacts of such an upbringing. The first line in the show ("The list began after her first attempt") instantly immerses us in both poles of the opposition that will play out here, suicide versus a list of the Brilliant Things which (Ice Cream, People Falling Over) should draw one into life's embrace. There is an actual List; the juvenile self of the narrator recalls initially creating it for the very purpose of dissuading his mother from trying again after that referenced attempt (which we know immediately must have been unsuccessful because it is only the "first"). Then other characters, aided and abetted by the audience, will collaborate with him to increase the List's size and scope. There is no denying the force of the List and the things on it; there is also no denying the force of the depression opposed to it.

And in a sense, that's it. That's what this show does for slightly more than an hour: pit what Hamlet called self-slaughter against the Brilliant Things. But such a programmatic summary barely gives a sense of the experience of the show, and might leave puzzling the success it's had. The biggest unreferenced ingredient is how funny it becomes. It is amazing, what wit can do to alleviate a sense of loss and dread, and amazing how simple-seeming are the devices from which such wit may spring. For instance, the narrator recounts his experience as a child being driven by his father to the hospital where his mother was kept after that "first attempt."

To every statement of the father's, now voiced by the narrator, the audience member recruited to stand in for the narrator's seven-year-old self must ask "Why?". The questioning starts over something trivial, a direction for the child to buckle his seatbelt. The father answers that first "Why?", and then attempts to answer a second "Why?" directed to the first answer, and keeps on answering each succeeding "Why?" until, in short order, he is enmeshed in cosmic (and comically absurd) imponderables: checkmate in only a few moves, as the father acknowledges having no idea why it takes 24 hours for the world to turn. But at the same time, we know that the real reason the panic-stricken child perseveres in asking "Why?" is that the question stands as a proxy for deeper, less safely-articulable uncertainties, i.e. what is wrong with his mother, and what does her condition mean for their future as a family? And the father's inability to answer the seatbelt questions is a proxy for his inability to answer or even address his child's deeper and also unanswerable anxieties. That kind of thing can be heart-rending, even as we laugh.

There can be rational decisions to end one's own life, but when such decisions are driven by most kinds of depression, which by definition are not rational, no one else, especially no one else touched by it, can make sense of it. And no string of "Whys" will bring us closer to an explanation. But comedy can at least supply insight into the dilemma.

Single Carrot's staging of this piece seems pandemically-driven but also a logical extension of the changes the company has been going through. Since even before the company gave up its space in Remington a few years back, it began experimenting with unconventional theater spaces, including moving a single evening's theater through several different locations, holding a play in the basement of an historic mansion, and now, logically enough, this: putting on small-audience stagings of the same show in residential backyards, a new yard each week for four weeks. And, depending on the evening, the narrator will be enacted by one of three different actors. The night I saw it, the performer was company member Matthew Shea. Other nights, it might be company member Lauren Erica Jackson or company member Meghan Stanton.

I thought Shea was terrific. His ability to morph into a little boy was touching, as was his comic stumbling through the colossally-difficult process of asking out a young woman on a date, later in his character's life. (Well, actually, in this production, unlike the original, the syntactically-awkward deployment of gender-neutral pronouns makes it impossible to determine the sex of the love object and later spouse, but at least in the original, the offstage character was female. Perhaps the language was changed to avoid making the script vary when female performers were filling the role.) I liked Shea's joking way of coaxing audience members into participation, which required repartee and quick adjustments. If this theater thing doesn't work out, he should have a future in standup.

I've seen both Jackson and Stanton before, and I have no reason to doubt they'll also do fine. And I'd imagine that, even without the opaque pronouns, this would be the kind of role that should work equally well with any skilled adult performer. Just as the script proves forgiving of audience members who find themselves unexpectedly reenacting the nightmare in which they're onstage with important things to say and they don't know their lines, so the universality of the subject should make the narrator's role forgiving for a variety of performers.

In short, this is a surefire evening of theater. With several unusual features, including a mention after the show of suicide prevention resources.

And, as should by now go without saying in these pandemic times, be prepared to show proof of vaccination and to wear a mask throughout the performance.

Every Brilliant Thing by Duncan MacMillan and Jonny Donahoe, directed by Paul Diem and Genevieve de Mahy, presented by Single Carrot Theatre, through September 26 at various locations around Baltimore, generically described in advance but specifically identified only when the ticket is issued. Tickets $15-$75, available at https://singlecarrot.secure.force.com/ticket/#/ or contact boxoffice@singlecarrot.com. Contains in-depth discussions of suicide and the issues surrounding it. Running time approximately 70 minutes.

Reader Reviews

Videos