Wesley Doucette

Wesley Doucette is a PhD student in French Literature at the CUNY Grad Center. His research focuses include French cultural institutions such as the Festival d'Avignon and the innovations of administrators such as Jean Vilar. He also studies contemporary European theatre culture. He received a Masters in Théâtre et Patrimoine from Avignon Université and received his undergraduate degrees from Kent State University in Art History and Theatre.

MOST POPULAR ARTICLES

October 11, 2024

This past spring L’Espace la Risée cabaret at the Rue Bélanger in Montreal welcomed a full-length drama, Deniz Başar’s Wine and Halva. The play employs a nearly improvisational dynamism as it explores the limitations of Western liberalism. In the play two young artist-academics dissect these questions. Their discourse intensifies as they navigate theoretical disagreements alongside their contrasting lived experience. This somewhat polemic discourse is buoyed by a coming-of-age friendship. The ingenuity of the staging in this intimate cabaret space highlights the creative collaboration of both performance and debate.

July 28, 2022

The 76th Festival d'Avignon officially concluded last night with Kae Tempest's The Line is a Curve at the Cour d'Honneur. This is the fifth album by Tempest. Previous works include Brand New Ancients, which I had the benefit of seeing some years back at New York's St. Ann's Warehouse. Their work in that instance was a transporting piece of storytelling. It was a very sober affair. The Line is a Curve started that way, but quickly became the cathartic rock concert to end the annual Festival.

July 28, 2022

Silent Legacy, now in performance at the Festival d'Avignon's Cloître des Cèlestins, asks questions about points of exchange. The relationship between the dancer and choreographer is complex. Literarily focused theatre's collaborative quality sometimes benefits from the boundaries made by script writing. In this way, the playwright has a product outside the performance. In most instances with dance, the work can only exist within the body of the performer. Silent Legacy presents its audience with two such points of exchange.

July 25, 2022

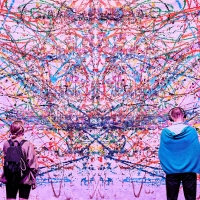

The text of Una Imagen Interior, a production by Spanish company El Conde De Torrefiel now in performance at Vedène's Autre Scène du Grand Avignon, is relegated to a bilingual surtitle board. Who does your mind cast in this role of narrator? A whimsical and childlike Björk might be appropriate. A resonant and poetic Maya Angelou might also work. My mind landed on the professorial tenor of David Attenborough. He was a good companion in a work that aspires to transcend 'frames.'

July 25, 2022

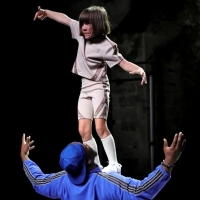

People often describe the imagination of a child as one of wonder or sweet innocence. The truth is, kids are weird and intense. They treat the oddest aesthetics with tragedian severity. François Chaignaud and Geoffroy Jourdain have captured such joyful oddity in TUMULUS, now performing in Avignon's La Fabrica. What results is a Seussian Gesamtkunstwerk.

July 25, 2022

Most times in Avignon, when a work is called something ominous like Blood, Bones, or, as is the case for Sophie Linsmaux and Aurelio Mergola's new work, Flesh, the worst is to be expected. The experience might be transformative, but it'll be a taxing journey. Happily, the two artists tackle questions of our relationships to our bodies with dark humor. Set in four vignettes at Avignon's Gymnase du Lycée Mistral, Flesh is Avignon's answer to Charlie Chaplin.

July 25, 2022

Choreographer Dada Masilo, a South African native, studied dance at Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker's school in Brussels. While there she developed an appreciation for the grand patrimonial dance-works. Her company, Dance Factory Johannesburg, has made a name for itself through oftentimes-comedic deconstructions of European classics like Swan Lake, and Giselle. In Le Sacrifice Masilo has decided to address a different dance classic, Le Sacre du Printemps. It was a long road to the Festival for Le Sacrifice, now performing in Avignon's Cour du Lycée Saint-Joseph. The piece has been twice canceled due to Covid. While her movement vocabulary lacks in imagination, the performances themselves were thrilling.

July 25, 2022

One of the most famous images of 20th century theatre is that of Brecht's Mother Courage who, when told she needs to remain incognito when her son is shot, offers a silent scream. In Ali Chahrour's Du Temps Où Ma Mère Racontait, now in performance at Avignon Université's Cour Minérale, Laïla Chahrour similarly unhinges her jaw into a scream, though it's anything but silent. Undergirded by musicians playing behind her, she cries into the audience, her voice rising into the starry sky. In the face of all the tragedy she has explored with her family, it is a resonating moment of catharsis.

July 25, 2022

According to a poll taken in 2016, a little more than half of all British people have seen or read Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. That number dips just below half for Macbeth and Midsummer. The Tempest rounds out the Top 10 at 22% engagement. Deep down in this list at 7%, tucked between Merry Wives of Windsor and Love's Labour's Lost, is Richard II. This obscurity was seen as a feature not a bug for Jean Vilar when he opened the first Festival d'Avignon with Richard II in 1947. Since this performance, the play has become something of a hallmark of French theatre. This year, Christophe Rauck adds his own directorial vision at the Festival's Gymnase du Lycée Aubanel with Micha Lescot in the title role.

July 21, 2022

Eulogies, obituaries, and post-mortems. There are many ways people digest a life ended. It's a daunting task to try to encapsulate someone else's life. The task becomes even more difficult when the existence you're attempting to reckon with is your own. Meng Jinghui's Le Septième Jour, now in performance at the Cloître des Carmes, shows a recently deceased man grappling with his life.

July 21, 2022

Hanane Hajj Ali considers a lot when she jogs through her home city of Beirut. She thinks about her compression socks and the pin for her headscarf. She thinks about the birds flying in the sky and, if all birds are praising God, what does it mean when one defecates on her? She thinks about great actors and great roles like Medea. She thinks about the catastrophes and scandals that have rocked her country for the past decades. With conviction and a deft hand, Hanane Hajj Ali takes us through her mind's pathways in Jogging, now in performance in Avignon's Théâtre Benoît XII.

July 21, 2022

Seated in the middle of a meters long bench in Avignon's Cour d'Honneur, Goska Isphording whirls through compositions on the harpsichord in front of her. Through deep concentration she executes rhythmic repetition with tongue twister like variations. It is understandable that Jan Martens has given her pride of place in his Futur Proche, which was premiered by Opera Ballet Vlaanderen last night in the Festival d'Avignon. Her presence elevated the dance composition, turning the dancers from plastic movement, to figments of her musical imagination.

July 19, 2022

The classic elements to create an effective magical illusion are smoke and mirrors. There might not be mirrors, but there is a great deal of smoke throughout Alessandro Serra's production of Shakespeare's La Tempesta (The Tempest), now in performance in Avignon's Opera House. This ubiquitous fog assists in creating many sublime illusions. Though for those who find Shakespeare enticing for pathos as well as panache, this fog blurs performances. With their faces obscured by fog and chiaroscuro lighting, Serra's take on The Tempest is an enchanting puppet piece.

July 18, 2022

If this Avignon season's other marathon project, the 13-hour Nid de Cendres, calls to mind a jewel box, Ma Jeunesse Exaltée calls to mind bathroom stall graffiti. The ten-hour long burlesque serves as the capstone to Olivier Py's tenure as artistic director of the Festival d'Avignon. In it he passes the baton, not to Avignon's next artistic director Tiago Rodrigues, but to a new generation of vibrant performers. Amongst this new generation is the indefatigable Bertrand de Roffignac, who performs a staggering harlequin marathon. Through the run time of the performance he never falters in precision or intensity. Indeed, on a scale of one to ten, the entire ensemble never lets the their work calm itself down past and eleven.

July 14, 2022

'Who's in charge here?' seems to be the question ringing though Anne Théron's powerful production of Tiago Rodrigues's Iphigénie, currently residing in Avignon's beautifully restored opera house. Power over memory, which dictates the proceeding actions, is bartered over between the characters and a chorus. There are memories they are unsure of. There are memories they are certain of. Sometimes a memory is a dead end, and sometimes it's the crack in the wall. Though it is not just power over memory that is being determined. Power over people, one's own actions, and the capacity to control one's own destiny are also in play. With the TNS, Théron has made the story of Iphigenia heart breaking and gripping, timeless and current.

July 14, 2022

It is clear that Marie Vialle finds the story of Simon Pease Cheney compelling. Her fascination with this 19th century American composer energizes her intimate Dans Ce Jardin Qu'On Aimait, now in performance at the Festival d'Avignon's Cloître des Célestins. Inspired by the novel by Pascal Quignard of the same name, Vialle and costar Yann Boudaud present a whimsical tale of redemption and artistic inspiration. If their production were in the 'Off', it'd be a highlight. However, their staging never unlocks the work past historical curiosity.

July 18, 2022

In Avignon's 'other theatre', a purpose built space some miles out of the city center, Bashar Murkus presents his new dance theatre piece Milk. It is an elemental meditation of death, rebirth, and disaster. It is this theme of disaster in particular that captivates Murkus's imagination. The piece occupies itself with the viscera of the human experience, and expresses that by having blood, water, and milk spill onto the stage floor. Though for all this connective tissue to the anxieties of the present day, its poetic visual language doesn't expand far past the realm of homage to theatre artists who came before.

July 11, 2022

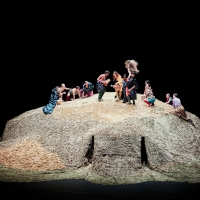

While describing the marginalization of theatre artists in early Christian society my theatre history professor once said, 'It must be a kind of witchcraft or at least magic. You are making something there that wasn't there before from your mere presence!' These words rang in my ears as I watched Simon Falguière's Le Nid de Cendres, a 13 hour long miracle currently running at The Festial d'Avignon's mercifully comfortable La Fabrica theatre. Separated into seven segments from 11 in the morning until midnight and after eight years of construction, the ambition of Falguière's company Le K is obvious. Though what astounds more than the run time is that this ambition is paired with boundless imagination, cutting wit, and deep generosity.

July 11, 2022

When it was announced that the 2022 Festival d'Avignon season would be headed by an adaptation of Chekhov in La Cour d'Honneur, I was skeptical. Chekhov's tragedies are often very cerebral. Their ultimate catastrophes are subtle and internal. How could something as fragile as a Chekhov character make itself realized in the chasm of La Cour d'Honneur? Kirill Serebrennikov answered this question through a liberal adaptation of Le Moine Noir, or The Black Monk, which turned the playwright's work into a surreal landscape. While the Cour d'Honneur still muffles subtelties, Serebrennikov's vision results in a few marvelous performances and resonating images.

July 11, 2022

What if Philip Glass led The Ramones? This is as good an introduction as any to Miet Warlop's One Song, which recently premiered in the Festival d'Avignon's Cour du Lycée Saint Joseph. The title, One Song, is more or less accurate, as Warlop presents to the audience how one simple song can transform, hypnotize, and energize. It's an hour-long metaphorical treadmill, neatly paired with a very literal treadmill that singer Joppe Tanghe performs on at a brisk jog for roughly the duration of the piece.

Videos