Kristin Salaky - Page 6

November 2, 2009

Michael Dale's review of Memphis, the new Broadway musical. The verdict is positive: Memphis is bursting with gutsy story-telling, convincing performances and exhilarating moments that more than make up for a bit of predictability.

October 29, 2009

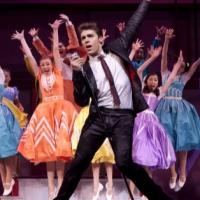

Michael Dale reviews Bye Bye Birdie and focuses on the positives in the production: dance ensemble numbers sparkled with real show-biz energy and livened up the production, Allie Trimm's solid performance, and Dee Hoty's presence.

October 26, 2009

Michael Dale reviews Oleanna and Circle Mirror Transformation. In 1992, when David Mamet directed the premiere production of his controversial play, Oleanna, the name 'Long Dong Silver' was still fresh in the minds of Americans who followed the Anita Hill/Clarence Thomas hearings. Susan Faludi's bestseller, Backlash, was urging women to stand up to 'The Undeclared War Against American Women' while Camille Paglia criticized the feminist movement for teaching women to see themselves as victims. Take Back The Night rallies on college campuses encouraged women to publicly announce the names of men who have raped them, though the definition of what exactly constituted a rape was still being publicly debated.

October 24, 2009

Those four Jews were in a room bitching again last Sunday afternoon. No, I don't mean The Marvelous Wonderettes. I mean Whizzer, Jason, Mendel and Marvin, also known as Stephen Bogardus, Jonathan Kaplan, Chip Zien and Michael Rupert. As any fan of neurotic, gay musical theatre will tell you, they were the quartet who first opened the 1992 Broadway production of Falsettos with William Finn's frenetic patter, 'Four Jews in a Room Bitching.'

October 22, 2009

No, that steady rumble you may hear and feel beneath your feet as you walk along 50th Street between 8th and 9th Avenues these evenings is not the A train making its way to Columbus Circle. It's the sound of laughing audiences having a swell time in the underground quintet of auditoriums called New World Stages. The former movie multiplex turned Off-Broadway house seems to be experiencing a happy renaissance, with its long-running anchor production, Altar Boyz, having been joined by laughter-inducing hits like The Toxic Avenger, Naked Boys Singing, My First Time and The Gazillion Bubble Show (which I haven't seen but I'm sure brings out many giggles from the youngsters). The hilarious Love Child, which previously ran at 59E59 will be moving in shortly, but first the welcome mat (and perhaps a red carpet) has been set for the center's new crown jewel as the Tony-winning Avenue Q completes its successful Broadway run and returns to its Off-Broadway roots.

October 19, 2009

In the 1920s, George S. Kaufman was one of the primary reasons New York was firmly establishing itself as the nation's capital of wit. Until his death in 1961, Kaufman could be called the quintessential New Yorker; continually working on Broadway as a playwright and director, reluctantly venturing out to Hollywood on occasion and regretting every moment of it and frequently quoted for his crackling cleverness ('I understand your new play is full of single entendres.').

October 18, 2009

If you're a frequent theatre-goer who has seen a decent number of Hamlets, or just a decent number of contemporary Shakespeare productions, chances are you'll get that old feeling of déjà vu watching Michael Grandage's Donmar Warehouse import, now parked at the Broadhurst for a limited run. While the mounting has its highs and lows, several directorial choices - once considered edgy, now pretty standard - keep this Hamlet draped in familiarity. The evening is lean, professional, fast-moving and not particularly interesting.

October 13, 2009

The old cliché says that New York audiences will always bow in awe and rampage box offices whenever a play from Great Britain washes upon its shores. But in recent seasons it seems that type of grandiose reception has been reserved for productions that land on our stages by way of Chicago. I have no idea what the new black may be but I have a strong hunch Steppenwolf is the new Old Vic.

October 11, 2009

If you take a whiff of air somewhere in the vicinity of the Schoenfeld Theatre these days and sense a slight essence of Mickey Spillane, it's undoubtedly due to the presence of Keith Huff's hardboiled police melodrama, A Steady Rain. A crackling good story told with potent language and a couple of terrific performances, this is a hearty plateful of good old fashioned meat and potatoes theatre.

October 9, 2009

Michael Dale reviews Charlayne Woodard's new solo piece The Night Watcher. From Jess Goldstein's flowing and flattering wardrobe to Geoff Korf's embracing lighting to Obadiah Eaves' jazzy sound design to the soft images in Tal Yarden's projections, everything about the production surrounds Woodard in a sweet and pretty atmosphere, perfectly framing the already irresistible words and performance.

October 6, 2009

I can't say I've ever really associated important events in my life with what I was wearing. Oh sure, I remember the powder beige tux I wore to my 1977 senior prom (my date picked it out) but since moving to New York I think it's safe to just assume I was wearing black whenever anything significant happened. Not so for the ladies of Love, Loss and What I Wore, a show that my female guest assures me gives an accurate portrayal of how women tend to hold important memories in the stitches of their apparel. And though such sentiments may be foreign to my nature (or perhaps nurture) I found the ninety-minute evening warm, funny (often hilarious), cleverly written and terrifically performed.

October 5, 2009

One of the most interesting chapters in William Goldman's classic book of commercial Broadway, The Season, involves the pre-opening troubles with the musical, Golden Rainbow. (Yes, I'm beginning a review of Little House on the Prairie with an anecdote about a glitzy Steve & Eydie vehicle. Just go along with me on this.) Although the musical had a huge advance sale thanks to the popularity of its husband and wife stars, everyone agreed the book was a disaster. But, according to Goldman, spirits were boosted a bit when rumors started circulating that Neil Simon - who was not only the hottest playwright on Broadway at the time but a guy known for anonymously helping to doctor other shows that were in need of laughs - would be coming in to punch up the script. In the meantime another writer was recruited and told that he didn't have to come up with anything clever; just to write a straightforward, competent book that made sense of the story. Neil Simon would come in later and provide the gags. (P.S. He never did.)

October 2, 2009

There's very little I can recommend from Vigil, Morris Panych's two-person play which I'll assume was meant to be darkly humorous and quirky, but ends up a rather dreary and frequently ugly ninety-five minute affair.

September 28, 2009

In his lengthy notes discussing the thought process behind his LAByrinth Theater Company/Public Theater mounting of Othello, director Peter Sellars explains how our view of Shakespeare's drama of an outsider Moor put into a position of power in an otherwise white society, must change in an era where Barack Obama can become President of the United States. His is an interracial Othello, with Latino John Ortiz (LAByrinth Theater co-founder) as the Moor, white actor (and longtime LAByrinth associate) Philip Seymour Hoffman as the underling Iago who tries to bring him down and an assortment of white, black and Latinos rounding out the company.

September 18, 2009

Some seasons back Peter O'Toole starred in a venture titled Jeffrey Bernard is Unwell, where he portrayed the London journalist whose 'Low Life' column in The Spectator chronicled his alcohol-fueled adventures among the town's Bohemians. When the festivities interfered with his ability to meet a deadline, the title phrase would appear in the space normally occupied by his scribblings. Those in the know... well, they knew.

August 31, 2009

The program notes for Scandalous People: a Sizzling Jazzical, advise us that Myla Churchill (book & lyrics) and Benny Russell's (music) new musical concerns Dewey Demarkov, a fictional black entertainer in pre-Depression Harlem who earned his song and dance chops playing demeaning stereotypes (sometimes in blackface) in white-run vaudeville houses and minstrel shows. As uptown Manhattan developed into a cultural center, Dewey formed an act with his future wife, Desiree Malinda, that evoked the kind of self-respecting class and sophistication the entertainers of the Harlem Renaissance became famous for. His innovative style made his speakeasy shows at The Do Drop Inn a top attraction.

August 26, 2009

I think it's important to report right from the outset that several times during The Public's outdoor production of Euripides' ancient Greek drama, The Bacchae, I looked down to discover that I was involuntarily tapping my toes to Philip Glass' new score. It's not that the master minimalist had peppered the centuries-old text with a collection of Jerry Hermanish showtunes, but that the tandem work of Glass' scoring for synth, brass and percussion and Nicholas Rudall's brisk, modern-sounding translation produced an irresistible give-and-take between speech and tone. No mere incidentals, Glass' airy, elongated pitches, frequently lush and at times strikingly accented, carry equal weight as the spoken words; echoing, answering back, subtextualizing and, most importantly, pushing the production toward its inevitable climax. If the composer's contribution is the 90-minute evening's most memorable, that's not to discredit the rest of director JoAnne Akalaitis' always interesting (if sometimes lacking for passion) production.

August 20, 2009

While calling the recent entertainment at The Triad Erotic Broadway may carry the same lack of appropriateness as expressed in the traditional arguments against the moniker Holy Roman Empire (It's really more 'cute and sexy' than erotic and the material's ties to Broadway are sporadic at best.), the cheery and playful variety show directed and choreographed by Tricia Brouk offers bouncy fun for all (legal) ages.

August 17, 2009

I'll readily admit to letting out a quiet, though not exactly inaudible, 'Wow,' as I entered the main auditorium at 59E59 and took a first glimpse at Kris Stone's New York apartment set for Primary Stages' premiere production of Cusi Cram's A Lifetime Burning. The high-ceilinged collection of sharp angles, backed by exposed brick, colored in blue pastel and embellished by furnishings by Eva Zeisel (I had to look it up), immediately grabbed my interest and had me anxious to meet whomever it was who might be living there.

August 13, 2009

While I certainly wouldn't suggest that Andrea McArdle has been living in the past, that's where she's spent most of her Broadway career; first getting noticed as the Depression-era social climber in Annie, and then nabbing roles in Les Misérables, State Fair and Beauty and The Beast (Hey, 'once upon a time' counts as the past.); not to mention playing young Judy Garland in the TV bio-pic, Rainbow. (Taking a cigarette break along the way to play Ashley in Starlight Express.

« prev 1 … 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 … 13 next »

Videos