Tales from the Blacklist: The Shadow of McCarthyism On Broadway

Go inside the stories of six Broadway luminaries, including Leonard Bernstein, Jerome Robbins and more, and their brushes with the HUAC and the Hollywood blacklist.

On a summer night in 1937, an audience gathered at the Venice Theatre in New York City, uncertain of what they were about to witness. Hours earlier, the U.S. government had locked the doors of the Maxine Elliott Theatre, abruptly shutting down The Cradle Will Rock, a pro-union, anti-corporate musical written by Marc Blitzstein and directed by Orson Welles. Officially, budget cuts had been cited as the reason, but the true cause was unmistakable—fear of political subversion.

Refusing to let censorship silence them, Welles and producer John Houseman led their cast and audience 20 blocks north to a new venue. There, under the glow of footlights, Blitzstein sat alone at a piano and began to play. One by one, the cast—prohibited by union rules from performing on stage—rose from their seats in the audience and delivered their lines from where they sat. The result was a spontaneous, electric act of defiance that turned an ordinary opening night into a legendary moment of artistic resistance. It was a harbinger of what was to come. Just over a decade later, a different kind of suppression would take hold of American theater.

During the Red Scare of the late 1940s and 1950s, Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), in their hunt to weed out communist sympathizers, set their sights on Broadway, branding playwrights, actors, and directors as communists. Careers were shattered, scripts went unproduced, and fear seeped into the creative process. Key figures of the Broadway community were called before the HUAC throughout its many proceedings, targeted for the content of their works and any unsavory political leanings, either real or perceived.

The new Broadway drama, Good Night and Good Luck, examines this period from a journalistic perspective, depicting the real-life confrontation between journalist Edward R. Murrow and senator Joseph McCarthy. The all-too relevant drama is a warning about the dangers of unchecked political power, its sentiments only growing more urgent as journalistic and cultural institutions find themselves laboring under the increasingly critical gaze of the current presidential administration.

Dive deeper into the history of the Red Scare and its impact on Broadway with the stories of six iconic artists, their brushes with the House Un-American Activities Committee, and its lasting impact on their lives and careers.

Marc Blitzstein, Composer

After the groundbreaking 1937 premiere of The Cradle Will Rock, composer Marc Blitzstein remained a force in American musical theater, but his career was marked by both artistic triumph and political persecution. While he continued to push the boundaries of politically charged theater, the rise of McCarthyism cast a long shadow over his work.

After the groundbreaking 1937 premiere of The Cradle Will Rock, composer Marc Blitzstein remained a force in American musical theater, but his career was marked by both artistic triumph and political persecution. While he continued to push the boundaries of politically charged theater, the rise of McCarthyism cast a long shadow over his work.

Blitzstein was one of the few openly gay composers of his time, a rarity in an era when homosexuality was criminalized and could destroy a career. Though he was briefly married to writer Eva Goldbeck, who supported his sexuality, his openness made him a target for both social discrimination and political scrutiny. His radical politics further fueled government suspicion. Blitzstein was deeply influenced by Bertolt Brecht, the German playwright and Marxist theorist, who once called him “a true communist artist” for his ability to fuse leftist ideals with music.

His leftist views eventually led him to be called before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1958. He admitted to having been a member of the Communist Party in the 1930s but refused to name names. Though he avoided being fully blacklisted, his career suffered in an industry that had become increasingly wary of political controversy. Many of his opportunities dried up, and he was left in professional limbo—neither fully exiled nor fully embraced by the theatrical establishment.

Blitzstein spent his later years working on an ambitious opera, Sacco and Vanzetti, about the wrongful execution of two Italian anarchists in the 1920s. However, he never completed it. In 1964, while traveling in Martinique, he was brutally attacked and murdered by Three Sailors in what was believed to be a homophobic hate crime.

Leonard Bernstein, a longtime admirer and friend, (and fellow HUAC target) was devastated by Blitzstein’s death. Bernstein had credited Blitzstein as a key influence on his own work and later lamented, “Marc was a genius, and the tragedy is that he did not live to fulfill all his promise.”

Though Blitzstein’s career was curtailed by political persecution and personal tragedy, his legacy endures. His music, bold and unapologetically political, paved the way for socially conscious theater. And his defiance—whether in the face of government censorship or McCarthy-era intimidation—remains a testament to the power of art as resistance.

Photo Credit: NYPL Digital Collections/Pictured: Cheryl Crawford, Marc Blitzstein, and Harold Clurman

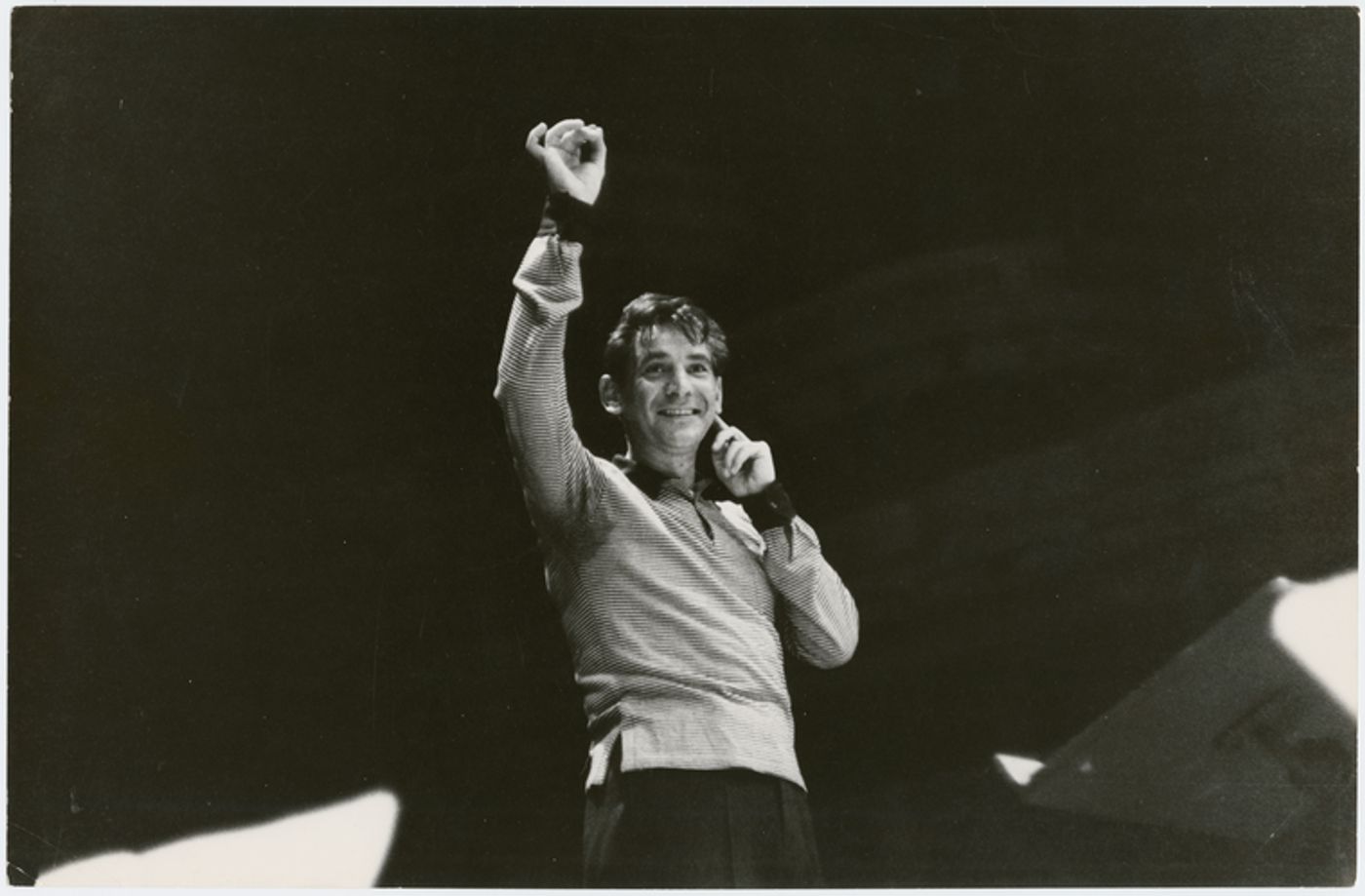

Leonard Bernstein, Composer

During the height of McCarthyism, one of America’s most celebrated composers and conductors, Leonard Bernstein, found himself under suspicion. Though he was never formally called to testify, his progressive politics, support for labor unions, and civil rights activism made him a target of anti-communist paranoia.

In 1950, Bernstein was listed in Red Channels, a publication that accused entertainers of Communist ties, effectively blacklisting many in the industry. Though he was never a member of the Communist Party, his associations with leftist causes drew government scrutiny. By 1953, he was forced to sign a loyalty oath to renew his U.S. passport, a requirement for those suspected of Communist sympathies. His career, particularly in television, was affected—networks hesitated to feature him, and he wasn’t given a major platform until 1954, when he hosted Omnibus, a cultural program that helped shape his public intellectual image.

Bernstein’s FBI file, which eventually grew to over 800 pages, detailed not only his political activities but also made note of his rumored homosexuality. During the Cold War, homosexuality was often considered a security risk, and the government likely saw this as another potential avenue for discrediting him. Even after McCarthyism faded, Bernstein remained under surveillance due to his activism. His outspoken opposition to the Vietnam War and his famous 1970 fundraiser for the Black Panther Party reignited accusations of radicalism. White House officials under the Nixon administration even considered ways to discredit him, fearing his cultural influence.

His political views also found their way into his music. Mass (1971), commissioned for the opening of the Kennedy Center, included themes subtly challenging Nixon-era politics and nationalism. It was a testament to Bernstein’s belief that music could be a form of resistance.

Photo Credit: NYPL Digital Collections

Lillian Hellman, Playwright

In 1952, playwright Lillian Hellman was summoned to testify before HUAC. Unlike many of her peers who either named names or remained silent, Hellman took a defiant stand.

In 1952, playwright Lillian Hellman was summoned to testify before HUAC. Unlike many of her peers who either named names or remained silent, Hellman took a defiant stand.

Though she had been involved in leftist causes in the 1930s, Hellman refused to cooperate with HUAC’s demands to inform on others. In a now-famous letter to the committee, she wrote, “I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year’s fashions.” She offered to speak about her own beliefs but would not betray colleagues. HUAC rejected her offer, and she was dismissed without a public hearing.

What many don’t know is that before taking her stand, Hellman reportedly considered naming names. She consulted with her lawyer and explored the possibility of cooperating but ultimately refused, feeling it would be a betrayal of her principles. Her letter to HUAC, while moral in tone, was also a calculated legal maneuver—by offering to speak only about herself, she aimed to avoid both perjury and contempt charges while still resisting the committee’s demands.

Though Hellman was never officially blacklisted, Hollywood effectively shut her out. Screenwriting opportunities dried up, and she found herself quietly but firmly excluded from major projects. Her longtime partner, writer Dashiell Hammett, was imprisoned for six months in 1951 for refusing to cooperate with HUAC, and Hellman suspected that his punishment was meant as an indirect warning to her.

Her resistance also put her in direct opposition to Elia Kazan, the famed director who chose to name names before HUAC. Hellman never forgave him, and their bitter feud lasted for decades. Even years later, when Kazan received an honorary Oscar in 1999, the controversy surrounding his cooperation with HUAC evoked Hellman’s defiant legacy.

However, her account of these events was not without criticism. In her memoir Scoundrel Time, Hellman portrayed herself as a bold and unwavering resister of McCarthyism. Critics, including the writer Mary McCarthy, accused her of exaggeration, with McCarthy famously stating, “Every word she writes is a lie, including ‘and’ and ‘the.’” Hellman sued McCarthy for defamation, but the case remained unresolved at the time of her death in 1984.

Photo Credit: NYPL Digital Collections

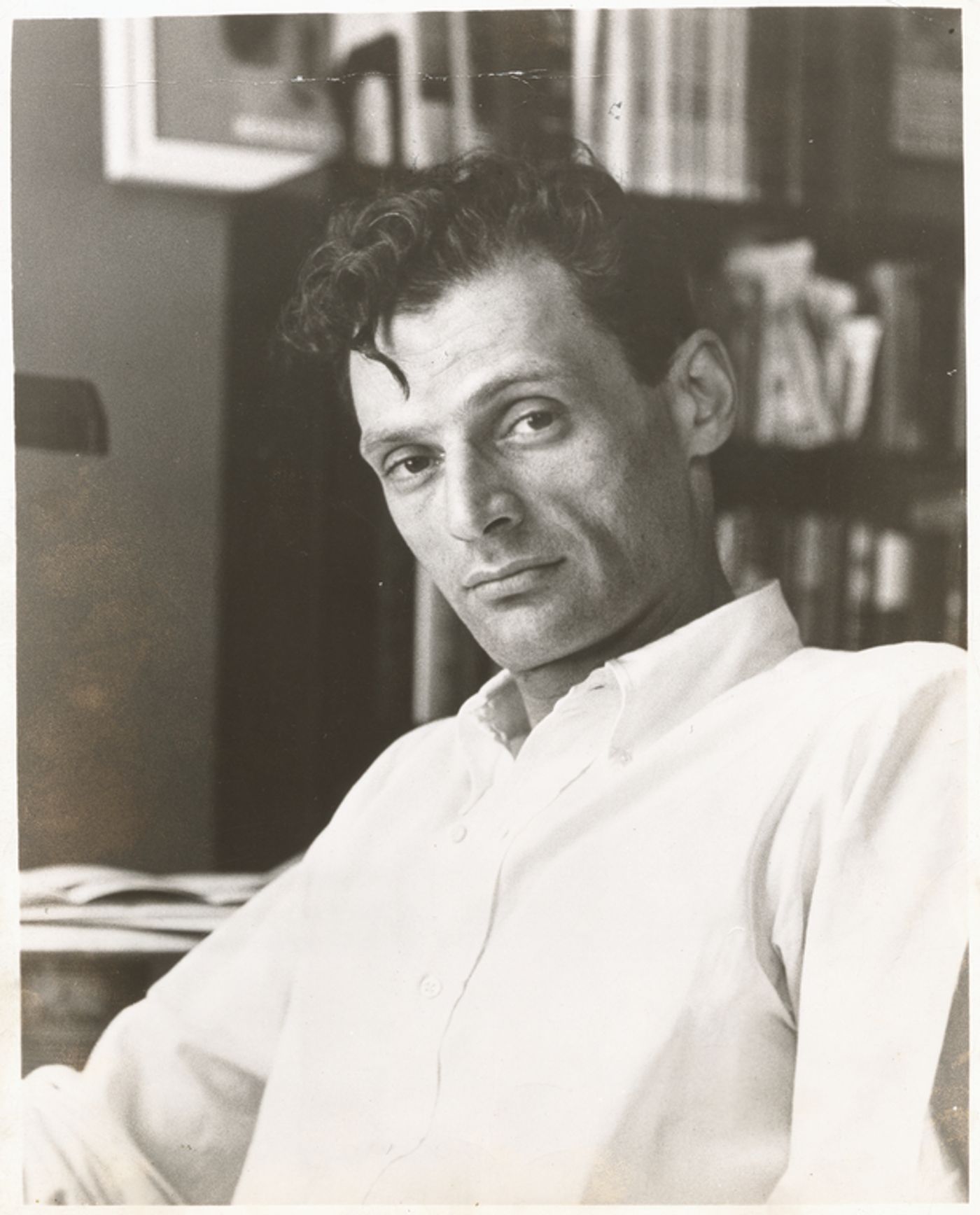

Jerome Robbins, Choreographer & Director

.jpeg) Jerome Robbins, the visionary choreographer behind West Side Story and Fiddler on the Roof, is remembered for transforming American musical theater. However, his legacy is also marked by his controversial decision to cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) during the Red Scare.

Jerome Robbins, the visionary choreographer behind West Side Story and Fiddler on the Roof, is remembered for transforming American musical theater. However, his legacy is also marked by his controversial decision to cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) during the Red Scare.

In 1953, Robbins was called to testify due to past ties to leftist organizations, including a brief association with the Communist Party in the 1940s. Fearing career destruction and the potential exposure of his homosexuality—another taboo at the time—he chose to name names. His testimony led to the blacklisting of several colleagues from The Group Theatre, an act that many in the artistic community never forgave.

What many don’t realize is that Robbins' decision was influenced by more than just professional concerns. HUAC had a history of pressuring witnesses by threatening to expose their private lives, and Robbins, a closeted gay man in an era of intense homophobia, was particularly vulnerable. Some historians believe that fear of being publicly outed was as much a driving force in his testimony as the fear of losing work. His lawyer strongly advised him to cooperate, subtly reinforcing the idea that refusal would not only end his career but lead to personal ruin.

Unlike figures such as Elia Kazan, Robbins’ cooperation wasn’t widely publicized at the time, allowing him to continue working with relatively little immediate public backlash. However, in the Broadway community, resentment simmered. Arthur Laurents, one of Robbins’ collaborators on West Side Story, never forgave him. Some scholars believe Laurents later took silent revenge through his work, creating the character of Molina in Kiss of the Spider Woman—a closeted man forced to betray others to survive. Decades later, when Laurents directed his acclaimed Broadway revival of Gypsy, he made a point to downplay Robbins' contributions.

Though Robbins' career flourished, he carried the weight of his testimony for the rest of his life. Colleagues noted that his obsessive perfectionism and notoriously harsh treatment of dancers and actors seemed like a form of self-punishment. Despite his artistic genius, the stain of HUAC followed him. Unlike some others who named names, Robbins never publicly apologized, though those close to him sensed that he was deeply haunted by his actions.

Photo Credit: NYPL Digital Collections/Frederick Melton (1951)

Arthur Miller, Playwright

Arthur Miller, one of America’s greatest playwrights, became a target of the HUAC during the height of McCarthyism. His 1953 play, The Crucible, used the Salem witch trials as a metaphor for the Red Scare, exposing the dangers of mass hysteria and false accusations. While the play was initially met with mixed reviews, it later became one of the most powerful critiques of McCarthyism, cementing Miller’s reputation as both a literary giant and a political dissenter.

Miller’s inspiration for The Crucible came after traveling to Salem in 1952 to study the original witch trial records. He was struck by the parallels between 17th-century Puritan paranoia and the McCarthy-era interrogations that were ruining lives based on little more than suspicion. Just as those accused of witchcraft had to either confess or be condemned, those targeted by HUAC were pressured to betray colleagues or face blacklisting. The play’s protagonist, John Proctor, who chooses integrity over self-preservation, became an enduring symbol of resistance against political oppression.

When The Crucible premiered in 1953, it was met with mixed reviews. Many critics found its message too overtly political, and some feared that endorsing the play might make them targets of HUAC. Audiences, too, were divided—some viewed it as an important critique of McCarthyism, while others dismissed it as an unnecessary provocation. However, as McCarthyism’s grip on America weakened, the play gained recognition as a brilliant and enduring allegory for government overreach and ideological persecution.

Miller’s opposition to HUAC became personal in 1956 when he was subpoenaed to testify. Some believed his high-profile marriage to Marilyn Monroe made him an even bigger target. Before his hearing, a committee official allegedly offered to cancel his testimony if Monroe would pose for a photo with him—an offer Miller refused. During his testimony, he admitted to attending leftist meetings in the 1940s but refused to name others. As a result, he was convicted of contempt of Congress, sentenced to a fine and a suspended jail sentence, though the ruling was overturned in 1958.

Despite the blacklist and legal trouble, Miller’s career remained strong. His defiance of HUAC further strengthened The Crucible’s impact as a political statement, and the play became a lasting symbol of resistance against ideological persecution. Decades later, its relevance continues, serving as a reminder of the dangers of fear-driven politics and the cost of maintaining one’s integrity in times of mass hysteria.

He later said of the piece, "The Crucible became by far my most frequently produced play, both abroad and at home. Its meaning is somewhat different in different places and moments. I can almost tell what the political situation in a country is when the play is suddenly a hit there it is either a warning of tyranny on the way or a reminder of tyranny just past."

Photo Credit: NYPL Digital Collections

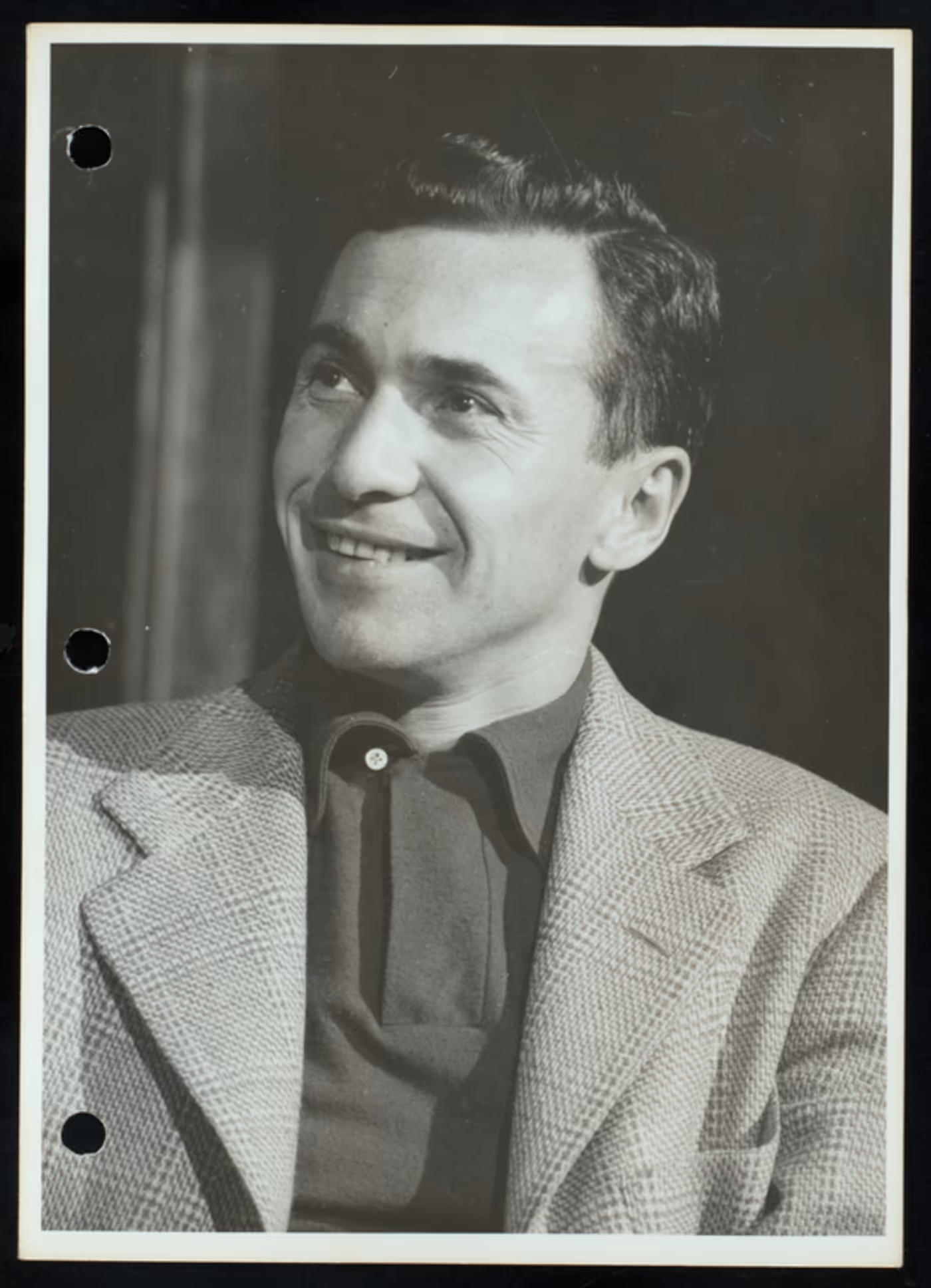

Arthur Laurents, Playwright & Director

Arthur Laurents, the celebrated playwright and screenwriter behind West Side Story and Gypsy, was deeply affected by the McCarthy era. Though never officially blacklisted, he was named in Red Channels in 1950, and the U.S. Army denied him a security clearance to work on a film. His Hollywood career stalled, forcing him to shift his focus to Broadway, where he would leave his most lasting mark.

Arthur Laurents, the celebrated playwright and screenwriter behind West Side Story and Gypsy, was deeply affected by the McCarthy era. Though never officially blacklisted, he was named in Red Channels in 1950, and the U.S. Army denied him a security clearance to work on a film. His Hollywood career stalled, forcing him to shift his focus to Broadway, where he would leave his most lasting mark.

With limited opportunities in Hollywood, Laurents moved to Europe for a time before returning to write West Side Story and Gypsy, cementing his reputation in theater. His relationship with Jerome Robbins, his West Side Story collaborator, remained tense after Robbins named names before HUAC in 1953—something Laurents saw as an unforgivable betrayal. Despite his later success in Hollywood with The Way We Were, he remained wary of the film industry, believing that mere suspicion of communist ties was enough to destroy a career.

His experiences with McCarthyism shaped much of his later work, often tackling themes of political persecution and the dangers of conformity. Even in his later years, Laurents held grudges—when he directed a 2008 revival of Gypsy, he barely acknowledged Robbins’ contributions. Though HUAC disrupted his career, Laurents outlasted the Red Scare, proving that talent and resilience mattered more than political pressures.

Photo Credit: NYPL Digital Collections/Fred Fehl, 1950

McCarthyism on Stage & Screen

The anti-communist hysteria of the McCarthy era not only blacklisted artists but also inspired plays, musicals, and films that explored government censorship, political persecution, and artistic resistance.

While works like The Crucible employed the allegory of the Salem witch trials to examine the Red Scare, other plays tackled the blacklist head-on, such as Are You Now or Have You Ever Been?, which recreated HUAC testimony, and Finks, a dramatization of the real-life blacklisting of playwright Joe Gilford’s parents.

Musicals also engaged with the topic. Kander & Ebb's Flora, The Red Menace followed a young woman caught between love and Communist activism, while Nick & Nora incorporated blacklisting into its detective narrative.

Beyond direct depictions of the blacklist, McCarthyism’s long shadow extended into later works. Tony Kushner’s Angels in America dramatized the fate of Roy Cohn, the notorious McCarthy-era prosecutor and Trump mentor. Kushner depicts Cohn dying of AIDS and haunted by the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg, a woman he successfully convicted of, and was later executed for, communist espionage.

Cohn's story has also been dramatized in the new film, The Apprenctice, which depicts his relationship with a young Donald Trump. Cohn is widely credited for mentoring Trump, imparting a "win-at-all-costs" mentality, along with agressive legal tactics, media manipulation, and a refusal to admit wrongdoing, approaches that Trump has adopted in his career in both business and politics.

Numerous films have explored the impact of the Red Scare, McCarthyism, and the Hollywood blacklist including, Good Night, and Good Luck (2005), Trumbo (2015), The Front (1976) and Guilty by Suspicion (1991), and The Majestic (2001). Other films to tackle the subject include High Noon (1952), and On the Waterfront (1954). Cold War paranoia plays out in The Manchurian Candidate (1962) and The Way We Were (1973).

The legacy of McCarthyism serves as a stark reminder of what happens when fear and political power collide to silence artists, journalists, and dissenting voices. The blacklist may have faded, but the instinct to control the arts and suppress criticism never truly disappeared—it simply evolved.

From HUAC to today’s censorship battles, the message remains the same: when political leaders seek to dictate what stories are told and who gets to tell them, democracy itself is at stake. The artists blacklisted in the 1950s didn’t disappear, and neither will those resisting now. History has always belonged to the voices that refuse to be silenced.