SWEENEY TODD, A History- Part 2: The Demon Barber Slashes His Way From Page To Stage And Beyond

Learn how Sondheim made Sweeney sing and how Mr. Todd made his mark on mass media.

Read SWEENEY TODD, A History- Part 1: Murder, Meat Pies, Men and Myths

The Demon Barber of Fleet Street first swung his razor from page to stage in 1847 when George Dibdin Pitt adapted The String of Pearls as a melodrama for the Britannia Theatre in east London. Produced under the title The String of Pearls; or, The Fiend of Fleet Street, the play opened on February 22, 1847, one month before the penny dreadful had completed its initial run, and became a long-running success.

For his version, Pitt made Sweeney, heretofore an ancillary villain, into the central figure. It was also in this alternative version of the tale that Todd acquired his catchphrase: "I'll polish him off." The play dazzled its audience with its shocking narrative along with an impressive bit of stagecraft, a working replica of the infamous barber chair that inverted to eject its occupant.

Following this production, Sweeney Todd, the Barber of Fleet Street: or the String of Pearls, premiered at the Old Bower Saloon, Stangate Street, Lambeth circa 1865, in a dramatic adaptation written by Frederick Hazleton.

The next notable production of the tale was Brian J. Burton's four-act musical melodrama, which premiered at the Crescent Theatre in Birmingham in 1962. It wasn’t until 1973, however, that the Sweeney narrative that we all know and fear began to take shape.

In a 2009 interview with Peter Stein at Wells Fargo Center for the Arts, Sondheim revealed the origins of Bond's play, explaining, “This guy Christopher Bond was an actor in the 1970s was on the road with a troupe and they were going to put on a Christmas show. They didn’t know what to do. And he thought, 'Gee, for Christmas, wouldn’t it be fun if we put on Sweeney Todd?'”

Unhappy with the available narrative, Bond saw an opening to deepen the character and, according to Sondheim, rewrote the story using aspects of The Count of Monte Cristo and The Revenger’s Tragedy to give Sweeney a dark backstory and sympathetic motive. (Spoilers ahead!)

Bond recast the villainous Sweeney as escaped convict Benjamin Barker, a barber who, after 15 years of wrongful imprisonment in an Australian penal colony, escapes and returns to London with a new name and a singular goal: to seek  revenge on the men who wronged him. Todd arrives in London only to find that the corrupt judge responsible for his conviction has defiled his wife, who has since committed suicide, and claimed his daughter, Johanna, as his ward, with designs on marrying her.

revenge on the men who wronged him. Todd arrives in London only to find that the corrupt judge responsible for his conviction has defiled his wife, who has since committed suicide, and claimed his daughter, Johanna, as his ward, with designs on marrying her.

Sweeney nearly gets his revenge when Judge Turpin arrives at his tonsorial parlor for a shave, but when his prey escapes, he vows to seek vengeance on humanity in general and begins to slash the throats of innocent patrons. He soon joins forces with pie maker, Mrs. Lovett, his former landlady, who repurposes the remains of his victims as filling for meat pies.

At play’s end, Sweeney ultimately gets his revenge by murdering Judge Turpin, but then unknowingly kills his own wife, who Mrs. Lovett had misled him into believing had died. After learning the truth, he kills Mrs. Lovett, but is in turn killed by Mrs. Lovett's assistant and surrogate son Tobias Ragg, who slits Todd's throat with his own razor.

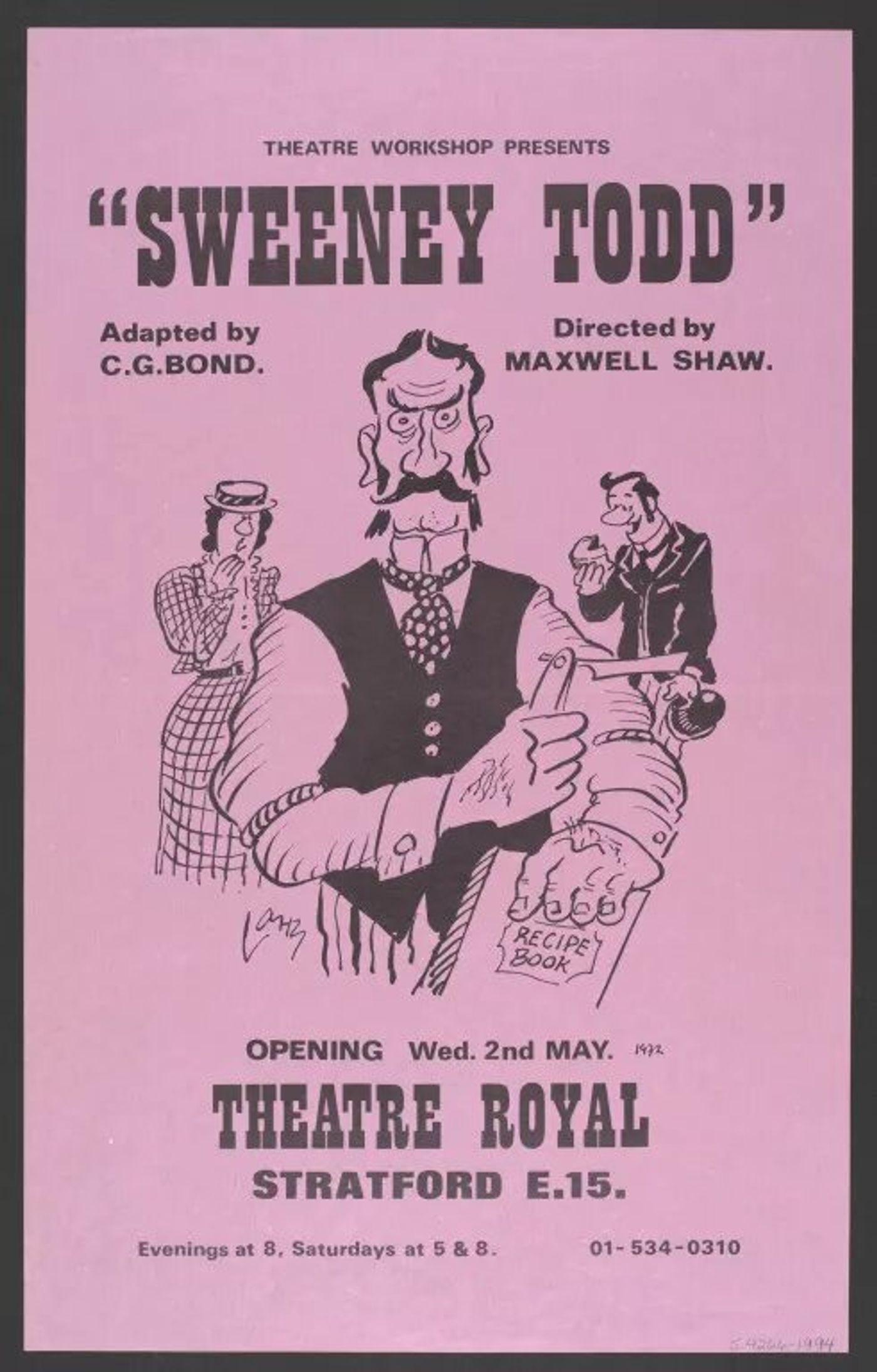

Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street was first presented by the Theatre Workshop at the Theatre Royal, Stratford, London on May 2, 1973. Directed by Maxwell Shaw, the production featured Brian Murphy as Sweeney Todd and Avis Bunnage as Mrs. Lovett.

Present at one of the performances was superstar composer, Stephen Sondheim, who, following a string of successes with Company, Follies, A Little Night Music, had come to take in the classic chiller.

Sondheim said, “When I saw the play at Royal Stratford East, it was quite a jolly evening. The play by Christopher Bond was done in a theater called Stratford East, which is sort of a pub theater. There was a p ub right next door and people would go get their pints of beer and then bring them into the theater and between the scenes of the play there would be singalongs with the audience- street songs, British ballads, that sort of thing. And the play was creepy/charming. It wasn’t really scary but it was really creepy, that story.” Sondheim was instantly inspired by Bond's take and began imagining a musical version of the story.

ub right next door and people would go get their pints of beer and then bring them into the theater and between the scenes of the play there would be singalongs with the audience- street songs, British ballads, that sort of thing. And the play was creepy/charming. It wasn’t really scary but it was really creepy, that story.” Sondheim was instantly inspired by Bond's take and began imagining a musical version of the story.

In his book, Sense of Occasion, original director Harold Prince describes his first encounter with his collaborator’s new notion: “I assumed from Steve’s description that it was a lighter-hearted work and that didn’t tempt me. So I dismissed it as a revengical. Steve, however, was on to more serious business and so I was interested.”

Sondheim recounted the meeting in a documentary chronicling the mounting of the show’s original West End production: “I showed him the script, and Hal is not the fan of melodrama and farce that I am. Those are, I think, my two favorite forms of theatre. And he said, 'Well, I could do this,' but he was clearly not very enthusiastic, and when Hal isn’t enthusiastic I immediately doubt myself, and I just got overcome.”

Prince counters, “The trouble was that I thought he was making a mistake; that I was the wrong director for it. I kept saying get Frank Dunlop, old boy. He’ll know how to give you that English street stuff and the fog and the billysticks along the grates and all that stuff. I couldn’t see beyond Sherlock Holmes, or something like that. I don’t mean it deprecatingly. That’s the way it looked to me. So I worked on it with him, but that’s the way it continued to look to me for over a year.”

wrong director for it. I kept saying get Frank Dunlop, old boy. He’ll know how to give you that English street stuff and the fog and the billysticks along the grates and all that stuff. I couldn’t see beyond Sherlock Holmes, or something like that. I don’t mean it deprecatingly. That’s the way it looked to me. So I worked on it with him, but that’s the way it continued to look to me for over a year.”

For his part, Sondheim set about crafting Sweeney’s score. In Bond’s play, Steve saw, in his words, an opportunity to write "a lot of creepy music." A longtime film fan, Sondheim sought to create sustained suspense through the cinematic convention of constant underscoring. He opted for dissonant, unresolved chord progressions to enhance feelings of uneasiness in his viewers.

To further unsettle his audience, Steve turned to a classic musical device that has struck fear in the hearts of listeners for over a century, the “Dies Irae”. The eight-note opening to the Requiem Mass for the Dead has been used to represent death in pop culture for over 100 years, most easily recognizable in the opening to the film The Shining. Sondheim wove the musical motif, which he said he found “moving and unsettling,” into nearly every song in Sweeney’s score, each time rearranging the theme into different melodic formations. This not only infused the score with a sense of inherent dread, but also created a series of distinct, yet subliminally related leitmotifs which created cohesion or controlled chaos as Sondheim required.

A lifelong fan of thrillers and psychological horror, Sondheim was also a great admirer of the film scores of Bernard Herrmann. Though Herrmann was best known for his work on the classic Hitchcock films Psycho, North by Northwest, and Vertigo, Sondheim found the composer's work via a little-known horror film, Hangover Square. The young Sondheim was so taken with Herrmann's score that he attended the film a second time to memorize the one of his concertos, the sheet music for which was shown for just a few seconds on screen. According to Steve, much of his score is an homage to Herrmann’s body of work, the concerto from his youth in particular. Herrmann’s influence is clearly evident throughout the show, particularly in what Sondheim referred to as Sweeney’s ‘madness themes’ where he borrowed Herrmann’s iconic shrieking string lines to give life to Sweeney’s fractured mind.

concerto from his youth in particular. Herrmann’s influence is clearly evident throughout the show, particularly in what Sondheim referred to as Sweeney’s ‘madness themes’ where he borrowed Herrmann’s iconic shrieking string lines to give life to Sweeney’s fractured mind.

When it came to Sweeney’s lyrics, Sondheim's most pressing challenge involved the class struggle inherent in Bond’s story. With characters sharply delineated by accents, the language of Sweeney Todd proved vast, with Steve creating measured cadences for the show’s aristocratic villains, Cockney argot for the peasantry, and romantic verse based in the King's English for the young lovers.

This convention proved particularly challenging in the case of the Beggar Woman. With information on her variety of bawdy Cockney colloquialisms scarce, Steve stole a trick from one of his West Side Story collaborators. Book writer Arthur Laurents had wholly invented the bebop street slang for the street gang the Jets, inspiring Steve to concoct some British street slang of his own. No one noticed for weeks, much to a smug Sondheim's delight, until Steve "made the mistake" of showing the script to British playwright Peter Shaffer, %20The%20New%20York%20Public%20Library%20Digital%20Collections_%201979_.jpg?format=auto&width=1400) who spotted every made up term instantly. Later, Steve met David Land, a British producer who had been raised in Cockney territory and, according to Steve, gave him “enough terms to keep a men’s smoker going for hours.”

who spotted every made up term instantly. Later, Steve met David Land, a British producer who had been raised in Cockney territory and, according to Steve, gave him “enough terms to keep a men’s smoker going for hours.”

In terms of the physical production, Sondheim saw the show as a chamber-sized piece in the same vein as the one he had enjoyed so much in London. In a notion predating the onsite confections of Waitress by decades, Sondheim envisioned the sale of ale and meat pies at the theater. So committed was Sondheim to his authentic concessions that on the first day of Broadway rehearsals, he had a lunch catered for the cast: a selection of meat pies that included bits of chopped celery emulating the human fingernail Tobias discovers in the filling of one of Mrs. Lovett’s pies.

“There were a lot of white faces around the rehearsal hall that day,” Sondheim laughingly recounted in 2009, adding, “If it weren’t for the various culinary laws in New York City, we could have had meat pies.”

In spite of his hopes for a scaled down chamber piece, the direction of Sweeney Todd would take a very different turn thanks to the influence of one key team member,

“I can sum that up for you in two words:” Sondheim told Peter Stein, “Harold Prince.”

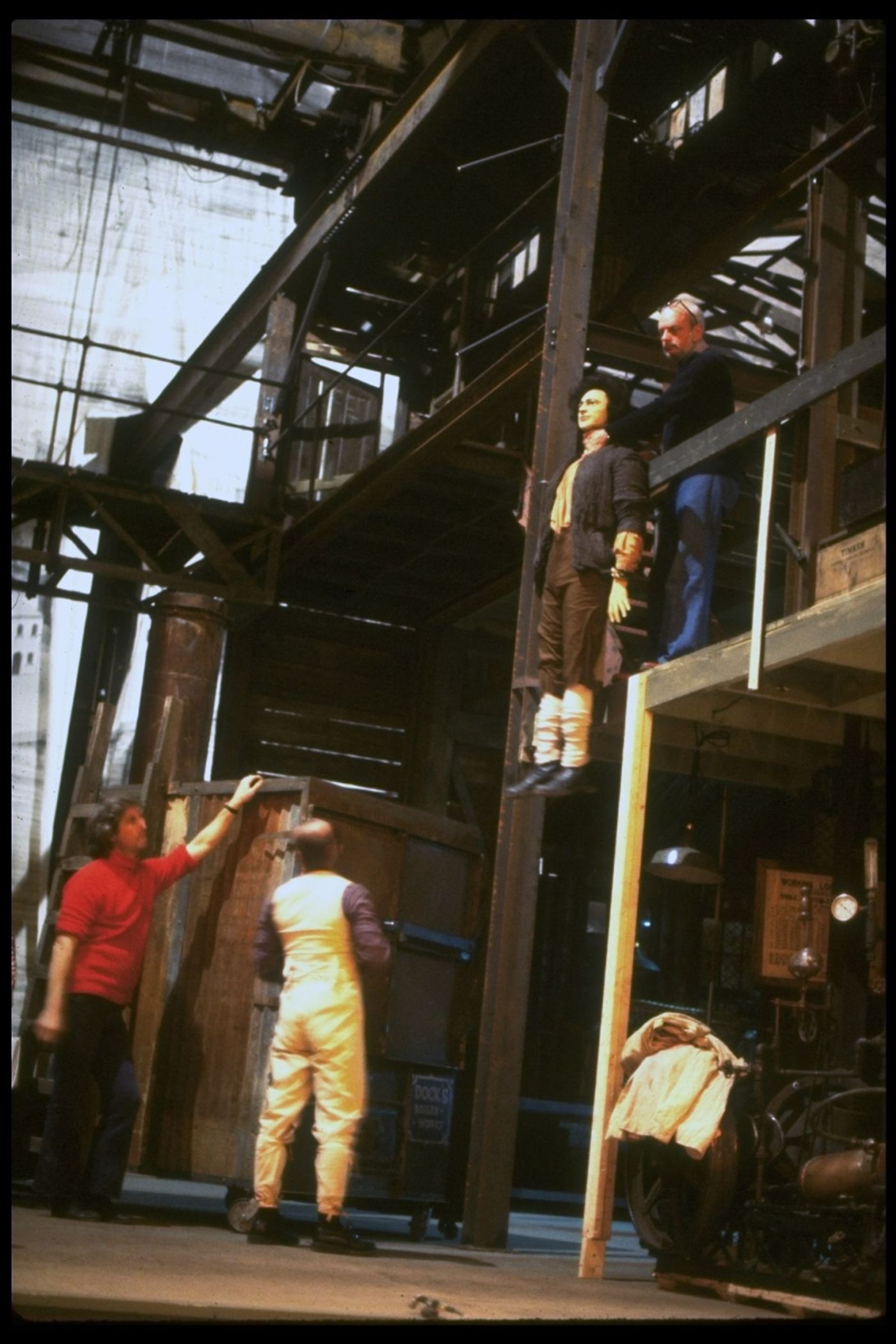

At this point, playwright Hugh Wheeler had signed on to write the book, along with Eugene and Franne Lee, who would design the set and costumes. It was Eugene who would help Hal find the central metaphor for his production: Industrial Age London.

In his book, Prince described “the collective slavery of sweatshops, assembly lines, the blocking out of nature, sunshine lost to the filthy fog spewing from the smokestacks of factories” as being the basis for his interpretation.

Hal said in 1980, “It wasn’t until we decided to encompass something larger, which is the class structure here. The terrible, frustrating struggle to rise up from the class in which you were born certainly was more dramatic in Victorian times. Suddenly it became about the Industrial Age and the incursions of machinery on the soul, and poetry, and a lot of high falutin’ stuff but, in fact, it’s what made it possible for me to direct it.”

Steve later said, “Hal always thought it was about the Industrial Age. I thought it was about scaring people.”

To bring Hal and Eugene's vision to life, the show’s producers paid $25,000 for The Remains of an abandoned Rhode Island factory and had its wrought iron exterior, gates, and machinery shipped back to New York to serve as the backdrop for the production.

Hal explained to the show's West End cast, "What we did was make a factory so that the%20The%20New%20York%20Public%20Library%20Digital%20Collections_.jpg?format=auto&width=1400) whole play takes place in a Victorian foundry. If you ask what they make in that factory, they make a show called Sweeney Todd. These people all work in the factory and the sunlight never hits any of them...the sunlight is always diffused through a filthy glass ceiling...And these people are trapped in this foundry."

whole play takes place in a Victorian foundry. If you ask what they make in that factory, they make a show called Sweeney Todd. These people all work in the factory and the sunlight never hits any of them...the sunlight is always diffused through a filthy glass ceiling...And these people are trapped in this foundry."

In addition to scaling down the vast playing space of the Uris Theatre (now the Gershwin) with its vaulted ceiling of grimy windows, the factory theme also upped the scare factor for the production. Like any other Victorian foundry, Prince's included a rather large factory whistle, which he installed at the front of the stage. Hal used his new toy to underscore Sweeney's murders, walloping the crowd with several nerve-shredding, high pitched shrieks throughout the evening.

"It's the most chilling sound. You'll hear it and it's quite alarming. The first time it goes off is at the beginning of the show and it has the effect of scaring the hell out of the audience. You hear a terrible scream from a dozen people in the house and then we get on with the show," Hal said.

Hal's whistle, like Sondheim's score, kept his audience in a state of sustained suspense as they waited in danger of the next blast. And, like Sondheim's score, it, too, convinced audiences watching a black musical comedy that they were really seeing a horror flick.

%20The%20New%20York%20Public%20Library%20Digital%20Collections_%201979_.jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

Prince later wrote, “I suggested it and auditioned levels of sound until it was almost unbearable. Audiences found it excruciating, but we loved to torture them.” Though Hal's Sweeney is the only to take place in a factory, mostly every other production of the show has opted to use the whistle.

Hal told the show’s original West End company on the first day of rehearsal, “The credo that’s kind of governed the work that Sondheim and I have done together is ‘less is more’. That old cliche that you’ve heard of. When we came around to do Sweeney Todd, I found another saying somewhere along the road that, 'Less is boring.’ And that, 'More is more'. And it was obvious that it’s been staring us in the face all these years. And so, we determined to go completely in the other direction and give more of everything than anyone had ever seen before.”

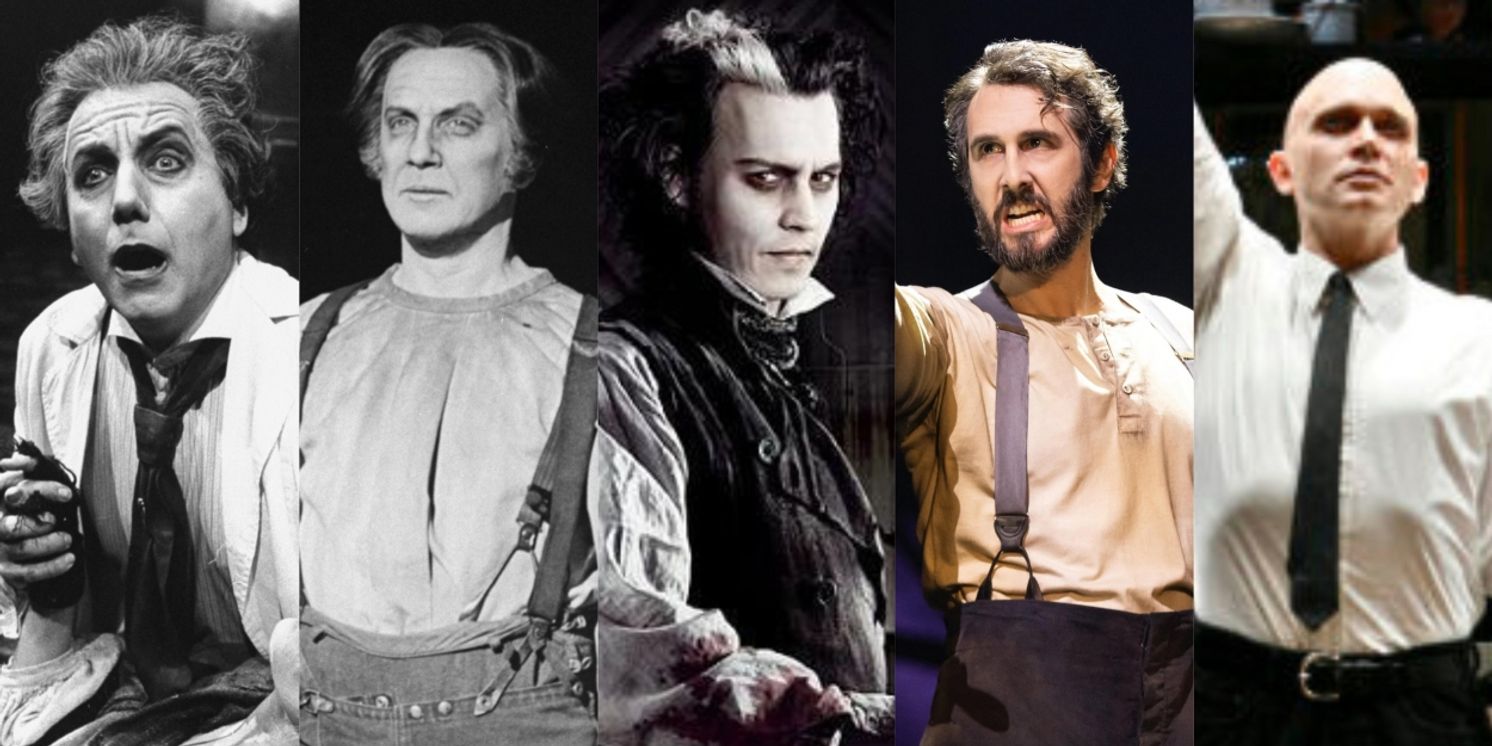

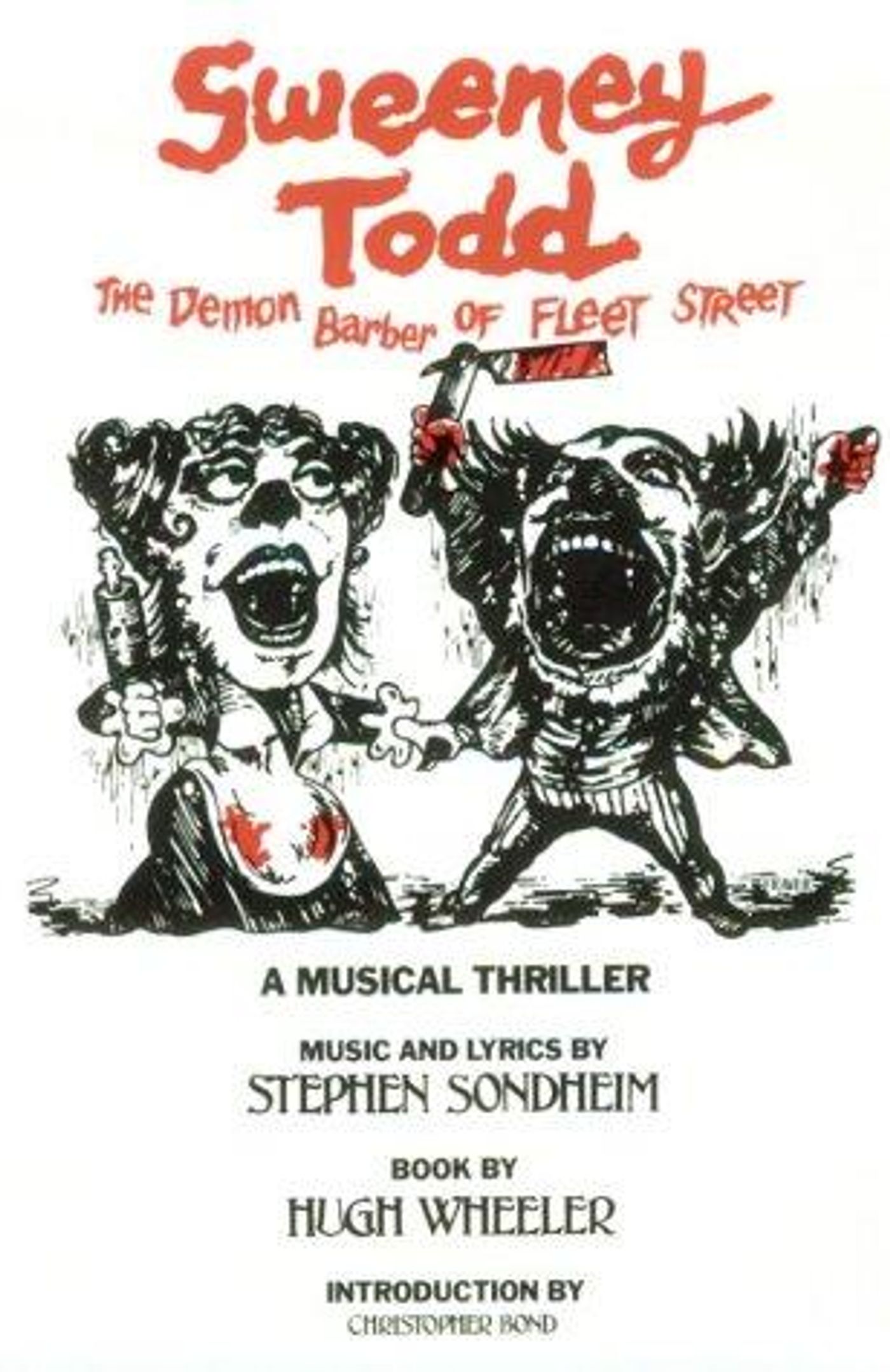

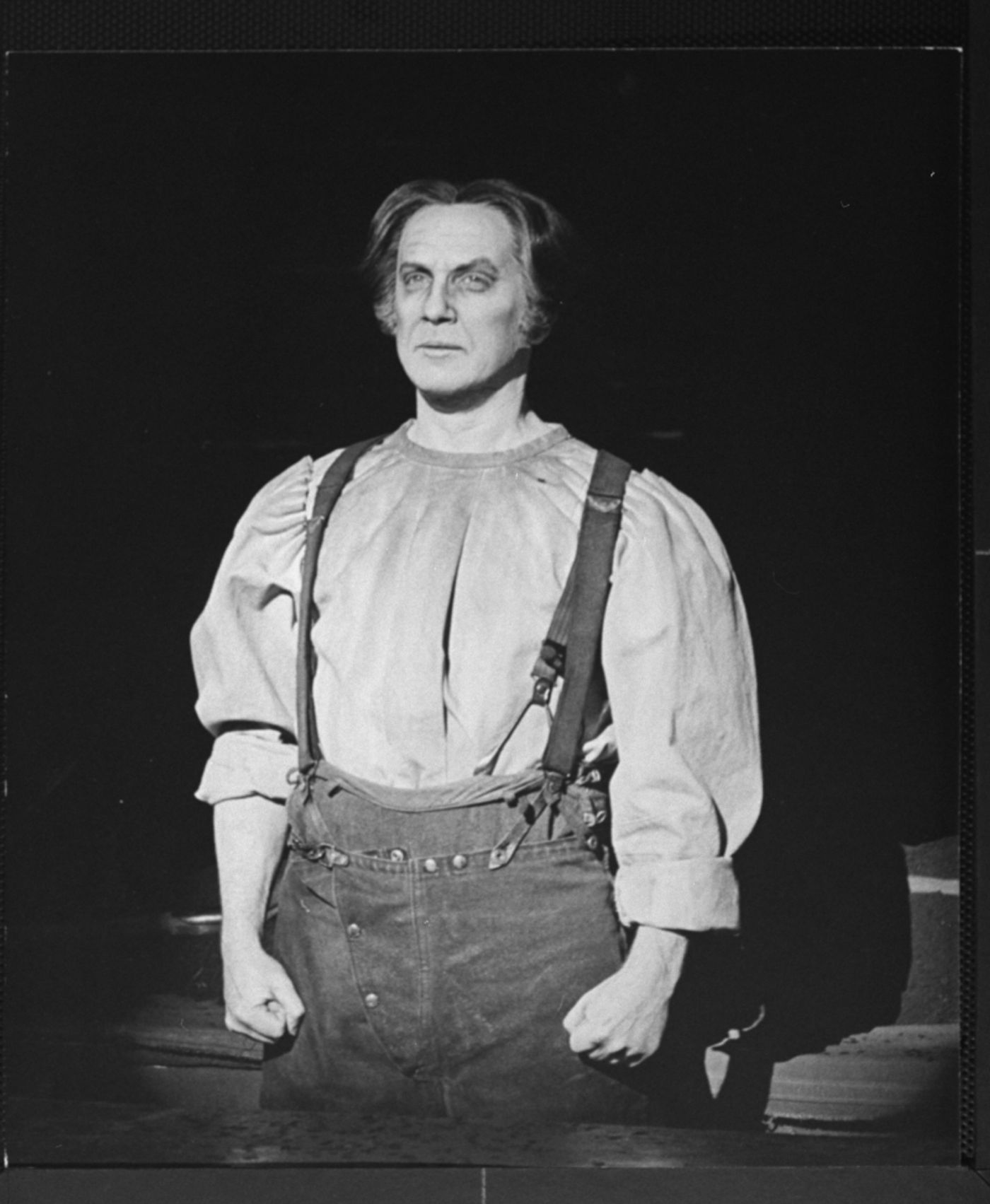

Sweeney Todd the Demon Barber of Fleet Street opened cold on Broadway in spring 1979 following a minimum number of previews. The production starred Len Cariou as Sweeney with Angela Lansbury as Mrs. Lovett. Lansbury, who was brought up in Poplar, East London, was raised with the legend of the Demon Barber, which was used during her girlhood as a taunt to bring naughty children to heel.

Two numbers were cut during previews, including a tooth-pulling sequence and a scene in which Judge Turpin self-flagellates as he watches Johanna through a keyhole. While the former was preserved on the original 1979 RCA cast recording, while the latter has been restored for later productions including John Doyle's 2005 revival.

Despite positive critical reception, the musical received a lukewarm review from Walter Kerr of The New York Times, who wrote, “We are without a perspective from which to view the mayhem, then, and can only sit back and admire the earnestness and the efficiency with which director Prince, composer Sondheim, librettist Hugh Wheeler, and -- most especially -- designers Eugene and Franne Lee have worked. The turntables spin, bodies are popped into an oven, we quite believe a filthy street hag when she speaks of the stench and the strange fire in the sky over London. We are plainly in the hands of intelligent and talented people possessed of a complex, macabre, assiduously offbeat vision. Unhappily, that vision remains a private and personal one. We haven't been lured into sharing it.”

mayhem, then, and can only sit back and admire the earnestness and the efficiency with which director Prince, composer Sondheim, librettist Hugh Wheeler, and -- most especially -- designers Eugene and Franne Lee have worked. The turntables spin, bodies are popped into an oven, we quite believe a filthy street hag when she speaks of the stench and the strange fire in the sky over London. We are plainly in the hands of intelligent and talented people possessed of a complex, macabre, assiduously offbeat vision. Unhappily, that vision remains a private and personal one. We haven't been lured into sharing it.”

The production was nominated for nine Tony Awards and won eight including Best Musical. Stephen Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler's Sweeney Todd played to capacity at the Uris Theatre throughout the duration of Len Cariou and Angela Lansbury’s contracts.

The show only ran another four months after Dorothy Loudon and George Hearn stepped in to replace them on March 4, 1980 and closed at a loss. The production then went on to tour North America (spawning a popular filmed version of the show starring Angela Lansbury and George Hearn) and play London’s West End where it received a frosty reception from UK critics. The show was capitalized at $3.5 million and took eleven years to recoup.

Sweeney returned to Broadway for its 10th anniversary in 1989 in a production starring Bob Gunton and Beth Fowler. The intimate production, originally produced Off-Broadway by the York Theatre Company at the Church of the Heavenly Rest, was affectionately referred to as "Teeny Todd." thanks to its small scale and minimal, synth heavy orchestrations. The production received four Tony Award nominations including Best Revival of a Musical, Best Actor in a Musical, Best Actress in a Musical and Best Direction of a Musical. The show also received a successful 1993 London revival that received Olivier Awards for Best Musical Revival, Best Actor in a Musical, Best Actress in a Musical, and Best Director Of A Musical. Sondheim praised the production for its chamber-style approach to the show, reminiscent of his initial vision for the work.

Sweeney’s next Broadway incarnation would prove its most inventive yet. In 2004, a director named John Doyle presented a minimalist revival of the musical at the Watermill Theatre in Newbury, England,

Newbury, England,

A regional nonprofit theatre, Watermill was operating on a shoestring budget and had adapted the piece considerably to pull off the massive story and score.

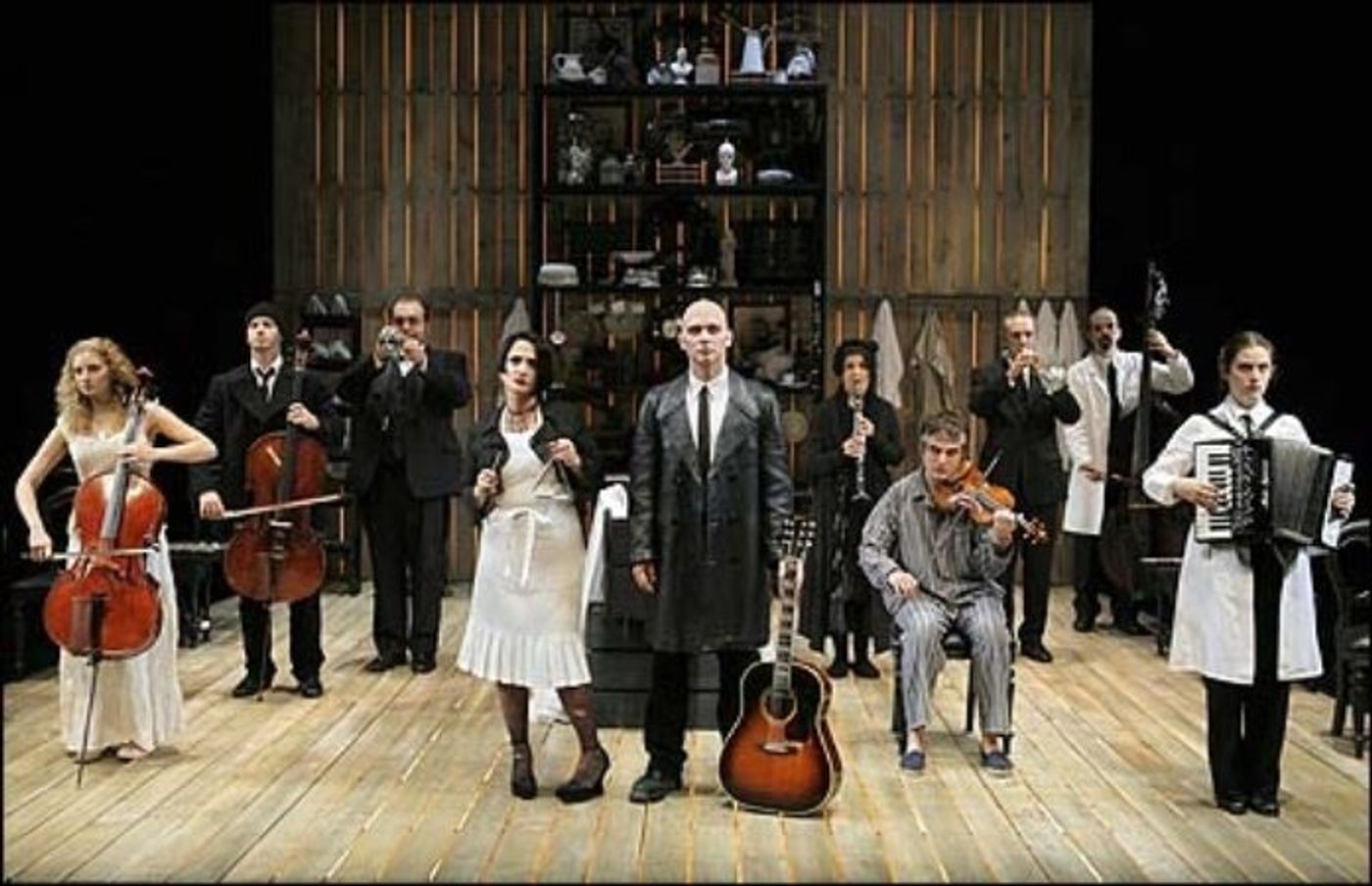

Most startlingly, Doyle’s production had no formal orchestra, instead employing a 10-person cast of actor/musicians to perform scaled down orchestrations by Sarah Travis. Visually, the trappings were sparse, taking more modern cues for the character’s clothing and hairstyles and using a coffin center stage to craft numerous settings.

“I was trying to find the least expensive way of doing this enormous piece with only nine or 10 people,” Doyle told The New York Times.

The massive emotions of Sondheim and Wheeler's show meeting the claustrophobic setting of the small venue proved highly effective, earning effusive praise from the show's composer and critics alike.

"When I first wrote this thing all I wanted to do was write a horror story, a Grand Guignol piece. Of all the productions I've seen, this is the one that comes closest to Grand Guignol, closest to what I originally wanted to do. I characterize all the major productions I've seen in terms of a single adjective. Hal's was epic. Declan Donnellan's production was exactly the reverse, it was very intimate. John's, for me, is the most intense," he said in 2005.

After a successful run at Watermill, the revival transferred to the West End, after which Doyle learned that producers wanted to transfer his revival to Broadway. “I really, truly thought they had lost their minds,” he told The New York Times.

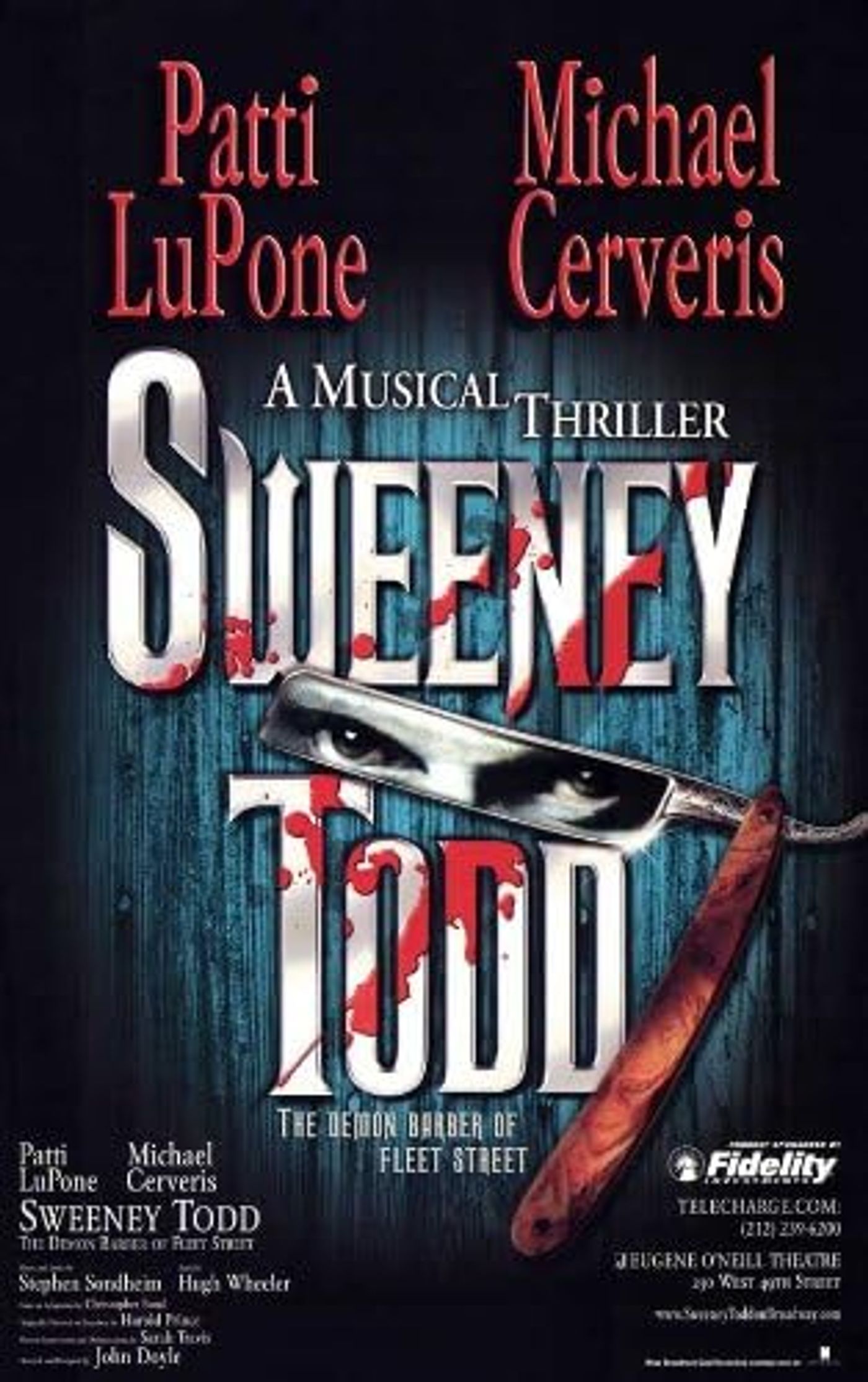

John Doyle’s Sweeney Todd began performances at the Eugene O’Neill Theatre in autumn 2005. As in the original production, the cast accompanied themselves on various instruments including title star Michael Cerveris, who also took on the role of the guitar.

For her part, Tony Award-winner Patti LuPone dusted off her tuba skills, honed in an the all-girls marching band in high school, to bring both Mrs. Lovett and the massive horn- which she named Irene- to life. LuPone had previously played the role in a staged concert version of the musical opposite former Sweeney, George Hearn.

According to her autobiography, Doyle instructed the cast to maintain eye contact with the audience wherever possible to enhance their unease. The deeper motivation of Doyle’s staging was that this incarnation is being staged in a madhouse, one in which the patients bring the story to life instead of actors.

“It doesn’t have to be big to affect an audience, it just has to be exciting,” LuPone said. “And, in our case, very scary.”

The production ran for 349 performances and 35 previews, and was nominated for six Tony Awards, winning two: Best Direction of a Musical for John Doyle and Best Orchestrations for Sarah Travis. Due to its small scale, Doyle’s production went up for $3.5 million (the same figure it took to make Hal Prince’s massive factory sing 26 years earlier) and it recouped its capitalization in nineteen weeks, spawning a national tour as well as a Toronto production.

Sweeney’s life on the screen began in 1926, in a now-lost 15-minute British silent film directed by George Dewhurst, featuring G.A. Baughan in the title role. The earliest surviving  film adaptation is the 1928 British silent film Sweeney Todd starring Moore Marriott as Sweeney Todd and Iris Darbyshire as Amelia Lovett.

film adaptation is the 1928 British silent film Sweeney Todd starring Moore Marriott as Sweeney Todd and Iris Darbyshire as Amelia Lovett.

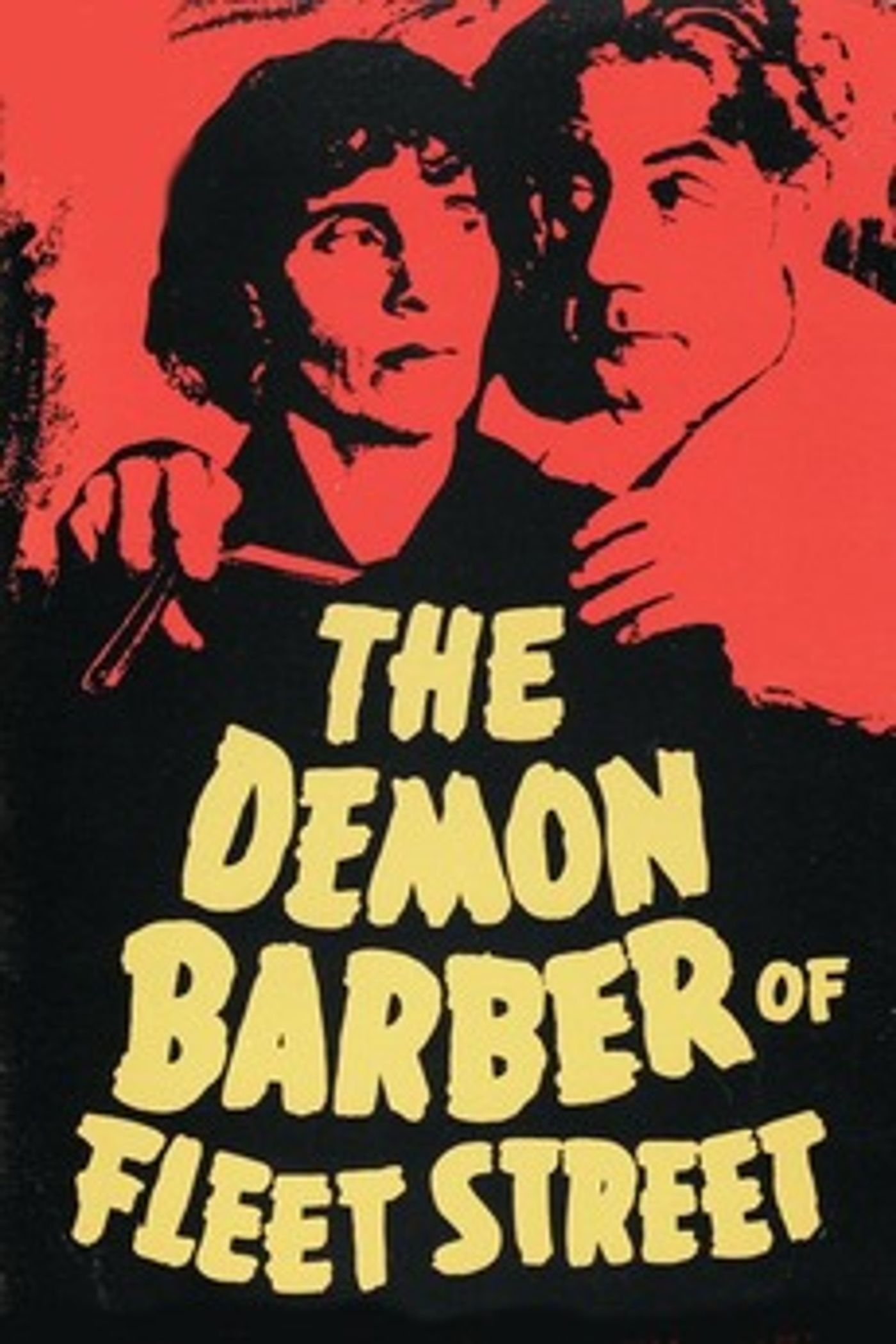

The Demon Barber made his way into features with the 1936 film Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street with the ironically-named Tod Slaughter in the title role and Stella Rho as Mrs. Lovatt. A 1970 horror film Bloodthirsty Butchers also took its cues from the myth, featuring John Miranda as Sweeney Todd and Jane Helay as Maggie Lovett.

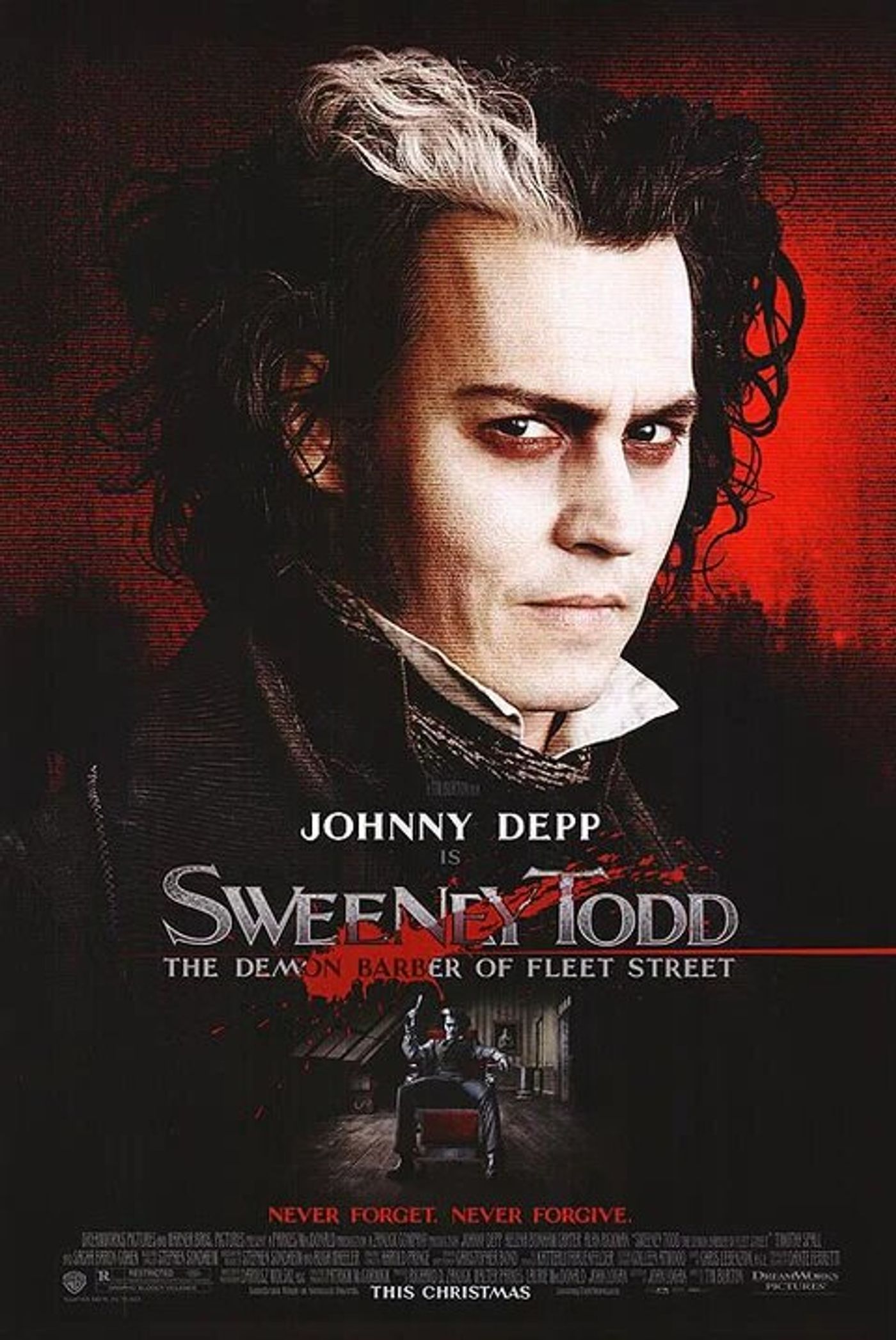

Sweeney would get his most high-profile film adaptation to date in 2007 when filmmaker Tim Burton used Sondheim’s version as fodder for a big budget movie musical.

A longtime fan, Burton, a maximalist known for his love of the macabre, found the show when he attended Hal Prince’s original West End production 12 times as a visiting college student from California.

"I was still a student, I didn't know if I would be making movies or working in a restaurant, I had no idea what I would be doing. I just wandered into the theatre and it just blew me away... I actually went three nights in a row because I loved it so much," Burton said.

Tim instantly saw the cinematic potential inherent in the tale's gore, sorrow, and madness, as well as the frenetic pacing of Sondheim and Wheeler’s storytelling and Hal Prince’s staging.

“I always felt it was like a silent movie with music in it — those old black and white horror movies,” He told the Times.

Burton met with Sondheim in the early 80s to discuss his vision for a potential film version of the show. In Steve's eyes, Burton proved the ideal candidate to bring Sondheim’s Sweeney to the big screen. Unsatisfied with the film adaptations of his work thus far, known cinephile Sondheim saw an opportunity to finally get one right, though nothing came of the initial meeting between the artists as Burton’s film career took off with a string of hits including Beetlejuice, Batman, and Edward Scissorhands.

In 2003, Burton stumbled upon an old drawing that he had done of Sweeney Todd and Mrs. Lovett, one that resembled his film’s eventual stars.

“They kind of looked like Johnny [Depp] and Helena [Bonham Carter],” Burton told The New York Times, “Johnny had gotten to the point where he was the right age. There was something about it that felt really right, even though I didn’t know if he could sing.”

Burton gave Depp, a favored collaborator, the cast album to gauge his response to potentially singing the part. Mr. Depp listened and responded, “I may sound like a strangled cat.”

Burton gave Depp, a favored collaborator, the cast album to gauge his response to potentially singing the part. Mr. Depp listened and responded, “I may sound like a strangled cat.”

Though production planned for Depp to work with a vocal coach, the actor ultimately felt that his Sweeney’s sound could be helped rather than hindered by his lack of technical prowess. He said, “It started to dawn on me that I knew what Sweeney sounded like before, and I knew that it was up to me to go far away from that. He needed to be, for lack of a better word, slightly more punk rock.”

To learn the difficult score, Depp studied Sondheim’s songs on breaks from filming the third Pirates of the Caribbean movie.

The film’s music producer, Mark Higham said of the task, “With Stephen’s music the melodies don’t roll off the tongue. They run around the scale. It’s hard for actors to get into the pockets of where the music really is.”

Helena Bonham Carter, the film’s Mrs. Lovett, put it more bluntly: “If you’re gonna learn to sing and you’re gonna do your first musical, it’s really stupid to do Mrs. Lovett.”

To earn the role, one she had coveted since girlhood, Helena worked intensively with a vocal coach for three months, ultimately earning the approval of Burton, then her husband who had been doubtful of her vocal capabilities. To prepare for the role, Carter rehearsed her songs while practicing baking techniques, in order to perfect the quick, syncopated rhythm of the music.

Both leading actors were given final approval from Sondheim himself though the composer had voiced previous concerns that Depp’s vocals might be too rock-oriented. Helena earned the composer’s endorsement after sending twelve audition tapes for his review.

To earn the role of rival barber, Pirelli, comedian Sacha Baron Cohen came with a slightly different approach, performing a one-man version of Fiddler on the Roof for Tim Burton.

For his Sweeney, Depp and Burton drew inspiration from Hollywood silent films and stars including Lon Chaney, Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi and Peter Lorre, an approach resulting in a frightening man-ghoul with sunken eyes, a mean maw, and a shock of white running through a thick, black pompadour. Carter, who had by her own self-admission run around with Mrs. Lovett-style hairdos as a child, brought a younger sensibility and softer appeal to her take on the daft baker.

Sondheim, long a critic of musical film adaptations that failed to truly adapt works to the New Medium, approved numerous changes to his score including the eliminations of the show’s opening number “The Ballad of Sweeney Todd” and its reprises. Other songs such as “Green Finch and Linnet Bird” and “God, That’s Good!” were shortened. Original orchestrator, Jonathan Tunick, upped the orchestra from 27 musicians in the original Broadway production to 78 players for the film.

In keeping with the tactile nature of musicals, Burton opted for practical effects and physical sets over digital renderings. “This is a musical,” he said. “Having sets helps you, it helps the actors, it helps the crew get into the right frame of mind. Just having people singing in front of a green screen seemed more disconnected.”

Burton also insisted that the film be bloody, as he felt stage versions of the play, which cut back on the bloodshed, robbed it of its power. For him, "Everything is so internal with Sweeney, that the blood is like his emotional release. It's more about catharsis than it is a literal thing."

“He had a very clear plan that he wanted to lift that up into a surreal, almost ‘Kill Bill’ kind of stylization,” the film’s producer Richard Zanuck said. “We had done tests and experiments with the neck slashing, with the blood popping out. I remember saying to Tim, ‘My god, do we dare do this?’”

Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street had its premiere at the Ziegfeld Theater in New York City on December 3, 2007, and was released in the United States on December 21, 2007 and the United Kingdom on January 25, 2008. The film received critical acclaim as well as the approval of its esteemed creator.

Tim Burton's Sweeney Todd received four 2008 Golden Globe nominations and won two including Best Motion Picture and Best Leading Actor in the Musical or Comedy genre. The film was included in the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures's top ten films of 2007, and Burton was presented with their award for Best Director. The film was also nominated for two BAFTAs and received three Oscar nominations at the 80th Academy Awards winning one for Best Achievement in Art Direction. For his terrifying take on Sweeney, Depp won the award for Best Villain at the 2008 MTV Movie Awards and the Teen Choice Awards.

Since the film slashed its way onto our screens, Sweeney's reign of terror has shown no signs of slowing down.

In 2012, Russian horror punk band Korol i Shut created a new rock-infused musical entitled  TODD. In 2014, Lincoln Center presented a concert version starring opera icon Bryn Terfel and Academy Award-winner Emma Thompson.

TODD. In 2014, Lincoln Center presented a concert version starring opera icon Bryn Terfel and Academy Award-winner Emma Thompson.

In 2015, Off-Broadway theatre company LAByrinth Theatre presented Aaron Mark's one-woman play Empanada Loca, starring Tony-nominee Daphne Rubin-Vega. The play follows an ex-convict who finds herself at the center of a bloodbath when an old friend offers her a room beneath his empanada shop. The play, said to be "inspired by the legend of Sweeney Todd," was adapted into the 2023 televisions drama, The Horror of Dolores Roach.

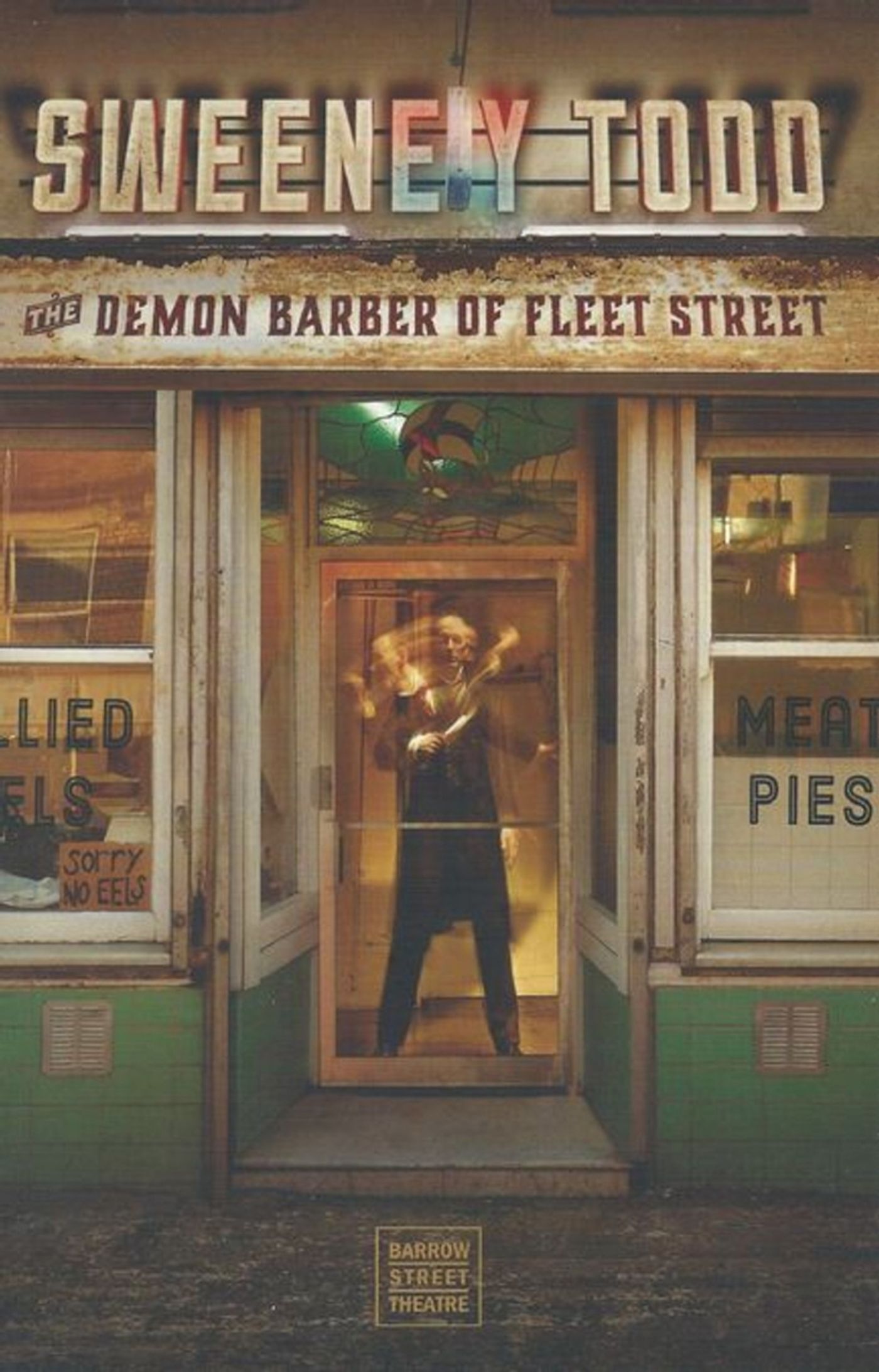

Over the past decade, Sondheim's Sweeney has received several high-profile productions in New York and abroad. One, in particular, brought Steve Sondheim's original intentions for the piece to life when Tooting Arts Club's immersive production set the show in a working pie shop. It wasn't long before producer Cameron Mackintosh stepped in to send the acclaimed production to Harrington's Pie Shop in the West End before moving on to a successful Off-Broadway run that transformed the Barrow Street Theatre.

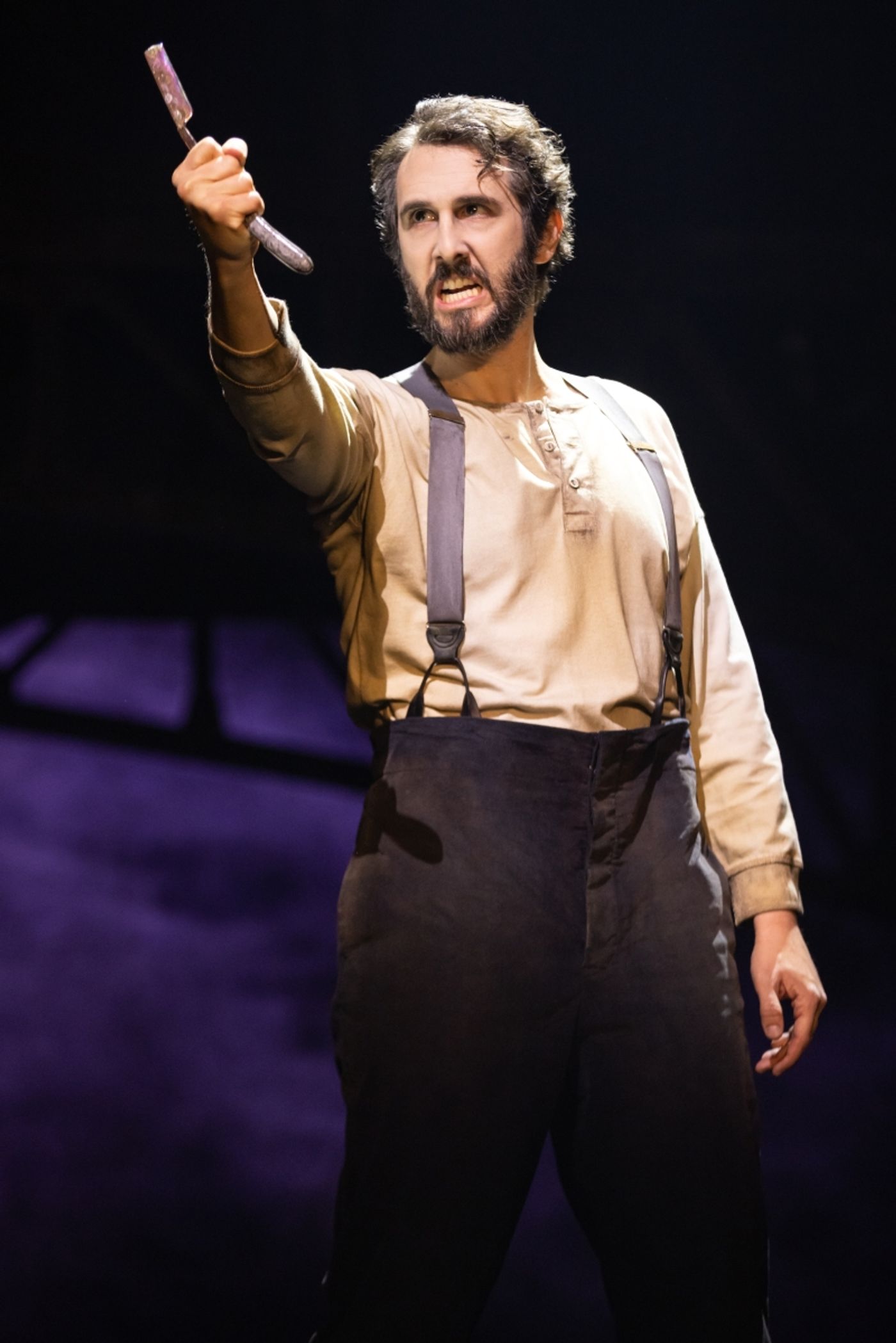

Sweeney struck back at Broadway on March 26, 2023 in a new Broadway production from  Tony and Emmy-winning director Thomas Kail, currently running at the Lunt-Fontanne Theater. The production stars Grammy-nominated singer and actor Josh Groban in the title role and Tony Award-winner Annaleigh Ashford as Mrs. Lovett.

Tony and Emmy-winning director Thomas Kail, currently running at the Lunt-Fontanne Theater. The production stars Grammy-nominated singer and actor Josh Groban in the title role and Tony Award-winner Annaleigh Ashford as Mrs. Lovett.

“Does New York need or want another Sweeney Todd, only four or five years after the pie shop? And the answer was: Maybe, if we give them something they haven’t seen in 40 years, a full-scale production with a full ensemble and a full orchestra.” producer Jeffrey Seller told The New York Times.

Though the size of the cast and the pit have been restored to their former glory, in terms of scale, the team were aiming for something approaching a midway point between the original Sweeney and the sparser, more intimate productions that have appeared in its wake.

“That production was influenced by Brecht; it was about alienation, distancing...That approach was enormously effective for them, and it is quite different from what we’re going to try to do.” Kail told The New York Times.

He elaborated, “What we’re really keen to explore is can you make something thrilling, something entertaining, something hilarious, something scary — and can we also break your heart?”

In returning the show to its 1979 glory, the design team dove into Hal's vision of a city whose denizens are sharply delineated by caste, crafting structures and silhouettes that would illuminate the class struggle at the heart of Sweeney's story. In a nod to Eugene Lee's original scenic design, Tony Award-winning set designer Mimi Lien has incorporated a nodule depicting Lovett's Pie Shop and Sweeney's Tonsorial Parlor along with a cast iron bridge that looms large beneath Tony-winner Natasha Katz's ghostly shafts of light.

A workshop of the production began three days after Sondheim's death in 2021. The beloved composer was excited for the new mounting and had planned to attend the workshop's final day. The piece is one of the last to earn Sondheim's personal seal of approval.

Thomas Kail's Sweeney Todd earned eight 2023 Tony Award nominations, including Best Revival of a Musical and continues to delight and thrill sold-out audiences to the current day with rumors of a 2025 national tour.

Since his first recorded appearance, Sweeney Todd the Demon Barber of Fleet Street has racked up eight stage adaptations, one ballet, half a dozen films, several novels, numerous notable film and television appearances (including a full-scale staging of Sondheim's opening number on The Office), and has inspired a number of songs, radio plays, and urban legends.

Stephen Sondheim's Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street is the winner of both the Tony and Olivier Awards for Best Musical. Since its debut, the show has gone on to a healthy life around the globe with notable productions staged in Australia, Budapest, Los Angeles, Barcelona, Finland, Washington D.C., Sweden, Ireland, France, Boston, Canada, Wales, Australasia, Mexico, the Philippines and South Africa. With its operatic overtones, Steve's version has also proven popular among opera companies. Numerous recordings have been made of Sondheim's score with number of high profile stars taking their turn in the murderous shoes of Sweeney and Mrs. Lovett including Christine Baranski, Brian Stokes Mitchell, Kelsey Grammar, Judy Kaye, Bob Gunton, Michael Ball, Julia McKenzie, Dennis Quilley, Sheila Hancock, and Imelda Staunton.

Tim Burton's film officially opened at the United States box office on December 21, 2007, in 1,249 theaters, and took $9,300,805 in its opening weekend. Worldwide releases followed in January and February 2008, with the film performing well in the United Kingdom and Japan. Overall, it grossed $52,898,073 in the United States and Canada, and $99,625,091 in other markets, accumulating a worldwide total of $152,523,164. Since its release, it has been widely assessed as one the greatest musical films of the 21st century. It was listed as number 490 on Empire's 500 Greatest films of all time in 2008 and it appeared at number 88 on its list of the 100 Greatest Movies Of The 21st Century in 2020.

In spite of its gruesome nature, there is an elusive quality to the persistent myth of the demon barber and his pal the pie maker that has kept audiences returning to Fleet Street for centuries.

Is it truth? Myth? An operatic tragedy? A black comedy? A musical thriller? A large scale commentary on British social politics? A claustrophobic chamber piece? A romance? A silent film come to life? A horror show? Of his version, Sondheim wrote in his 2010 memoir, "What Sweeney Todd really is, is a movie for the stage." Yet even the maestro himself struggled to define the work.

Horrifying, tragic, hilarious, profane, romantic- whatever the definition, it is a tale whose popularity is rooted in the timelessness of inhumanity, propelled by the most human of emotions- love, sorrow, rage, and yes, even madness. Whether we like it or not.

Upon playing the score for Judy Prince, the director's wife told Sondheim, “Steve, it’s the story of your life,” seeing parallels between the tale of Benjamin Barker and the wrongs perpetrated on Sondheim throughout his childhood. Of all Sondheim's musicals, Sweeney Todd is the only one whose germ came from the composer himself. In that way, perhaps the tale of Sweeney Todd is more personal than any of us would dare admit.

Hal Prince said of his relationship to the story, "I'd like to say here that revenge is not in my nature. But perhaps that's what scares me. Perhaps it is in my nature."

"Attend the tale of Sweeney Todd,

he served a dark and a hungry god.

To seek revenge may lead to hell,

but everyone does it, and seldom as well.

As Sweeney, as Sweeney Todd,

the Demon Barber of Fleet Street."

Images:

1) The cover of The Boy's Standard depicting the serial drama, Sweeney Todd the Demon Barber of Fleet Street.

2) Promotional image for Christopher Bond's Sweeney Todd the Demon Barber of Fleet Street at Theatre Royal Stratford.

3) Artwork for the original Broadway production of Stephen Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler's Sweeney Todd the Demon Barber of Fleet Street.

4) Director Harold Prince (R) overseeing construction of set for Broadway musical Sweeney Todd at the Peter Feller studios (New York) The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1978. Photo Credit: Martha Swope.

5)Len Cariou in a scene from the Broadway production of the musical Sweeney Todd The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1978. Photo Credit: Martha Swope.

6) Angela Lansbury in a scene from the Broadway production of the musical Sweeney Todd The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1978. Photo Credit: Martha Swope.

7) Len Cariou and Angela Lansbury in a scene from the Broadway production of the musical Sweeney Todd The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1978. Photo Credit: Martha Swope.

9) The original Broadway production of the musical Sweeney Todd The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1978. Photo Credit: Martha Swope.

10) Ken Jennings in a scene from the Broadway production of the musical Sweeney Todd The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1978. Photo Credit: Martha Swope.

11) George Hearn in a scene from the Broadway production of the musical Sweeney Todd The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1978. Photo Credit: Martha Swope.

12) Beth Fowler and Bob Gunton in a scene from the Circle In The Square production of the musical Sweeney Todd. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1989. Photo Credit: Martha Swope

13) Original artwork for the 2005 Broadway revival of Sweeney Todd.

15) The cast of the 2005 Broadway revival of the musical Sweeney Todd. Photo Credit: Paul Kolnik

16) Film poster for Sweeney Todd the Demon Barber of Fleet Street (1936)

17) Film poster for Sweeney Todd the Demon Barber of Fleet Street (2007) Credit: Dreamworks Pictures

20) Artwork for Sweeney Todd the Demon Barber of Fleet Street at Barrow Street Theatre (2017)

21) Josh Groban in a scene from the 2023 Broadway revival of the musical Sweeney Todd. Photo Credit: Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman

22) Josh Groban and Annaleigh Ashford in a scene from the 2023 Broadway revival of the musical Sweeney Todd. Photo Credit: Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman

24) Josh Groban, Annaleigh Ashford, and the ensemble in a scene from the 2023 Broadway revival of the musical Sweeney Todd. Photo Credit: Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman

Powered by

|

Videos