Review: THE MARGRIAD, OR, THE TRAGEDY OF QUEEN MARGARET at Avant Bard Theatre

With a stellar cast and a fantastic creative team, 'The Margriad' is a thoughtful exploration of power.

“There was a time when the people who started wars fought in them. Right or wrong, they were accountable.”

In modern times, it often feels as though the people are left to adjudicate the desires, whims, and grievances of their leaders without as much risk to the leaders’ lives themselves. While this has always been true to an extent – the use of wealth and power to purchase safety in some form or another has always been a part of warfare – it’s undeniable that social advancement through battle has largely fallen out of favor in the 20th and 21st centuries (though an argument can of course be made for the role the promise of social mobility plays in military recruitment). As the twenty-year conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan came to an abrupt and devastating close in 2021, Director and Adapter Séamus Miller considered the distinctly disparate impacts the war had on those who waged it, and those who fought in it.

Miller turned to Shakespeare’s History Plays, which depict the period from the reigns of Richard II (1377-1399) through Richard III (1483-1485), and encompass the War of the Roses, a century of civil war in which England’s throne oscillated between the House of Lancaster and the House of York, two rival houses (“both devoid of dignity,” as the Chorus quips) with claims to the Plantagenet throne following the death of Edward III in 1377. The fight also coincided with and was exacerbated by England’s ongoing Hundred Years’ War with France. Miller noticed that amidst the retelling and reframing of the bloody civil conflict, one character, Queen Margaret of Anjou, the French princess married to King Henry VI, appeared in four of Shakespeare’s six plays on the time period – tied with Sir John Falstaff for most appearances of any Shakespearean character. Queen Margaret is a striking figure in the Histories, reflecting the large role she played in life, often ruling in her husband’s stead due to his mental health, and leading the Lancaster faction both on and off the battlefield. She is present for many of the pivotal moments, including the victories at the Battles of Wakefield and St. Albans, and the defeat and death of her son at the Battle of Tewkesbury, leading Miller to create their own adaptation of these scenes in The Margriad, or, The Tragedy of Queen Margaret, which premiered at Avant Bard Theatre this weekend.

The Margriad refocuses the Shakespearean histories on Margaret’s path throughout the plays – from her rise to Queen of England to her struggles to hold onto her husband’s crown to her final losses. Her character’s ambition and conviction drive her to battle and unexpected alliances & betrayals over the years, and each turn only hardens that determination into a resentment where all that lingers after her final downfall is her curse that her enemies suffer the same fate as she and her line. Miller frames Queen Margaret as a warning for those who are willing to give – and lose – everything in the pursuit of power.

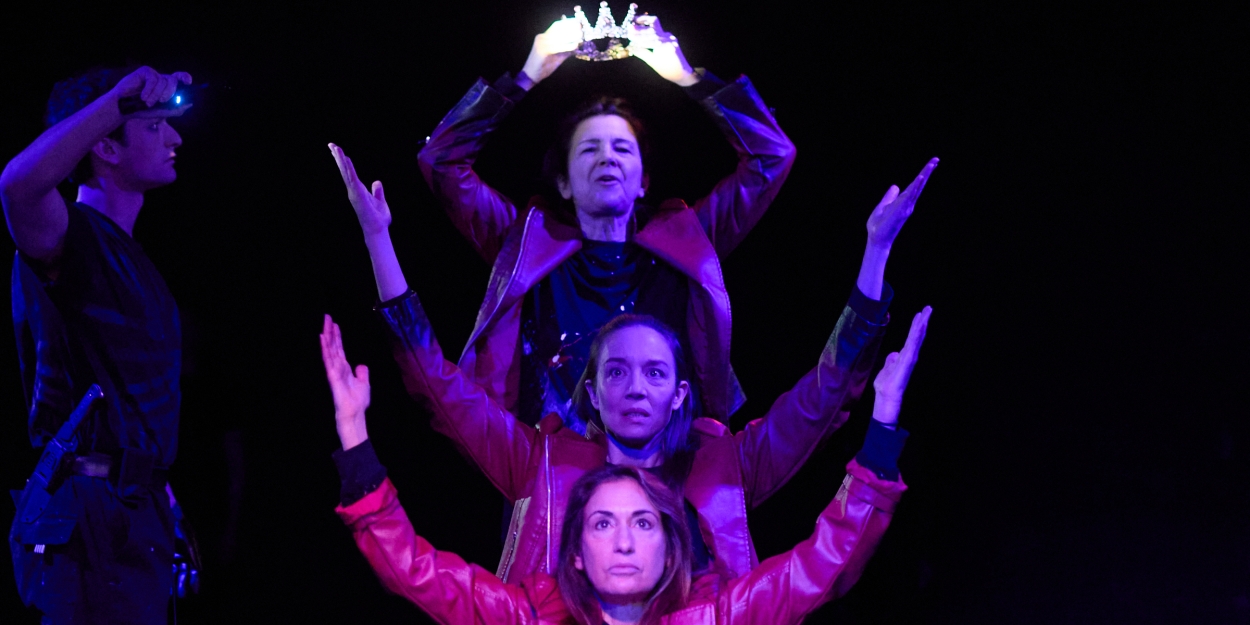

Miller’s adaptation at Avant Bard is a compelling way to study this fascinating figure. The production features seven actors, each taking on a mixture of key and background characters throughout the events, with three performers portraying Margaret at the different stages of her life: the ambitious woman full of political prowess and intrigue, the queen at the forefront of battle, and the bitter woman whose only balm to her losses is the knowledge that her enemies will fall as well. The technical elements are sparse and often dark, centering the production around the performances and storytelling rather than elaborate sets and costumes; this also allows the cast to nimbly change characters and scenes, pushing the play forward through a long, complicated, and bloody history while keeping the focus on the heart of the tale – after all, Miller is attempting to condense nearly four Shakespearean plays (with some nods to a handful more) into three acts, and the only way to do that successfully is to have a clear, direct path – though some of the asides recognizing what’s been cut are an entertaining way to acknowledge the abridgement.

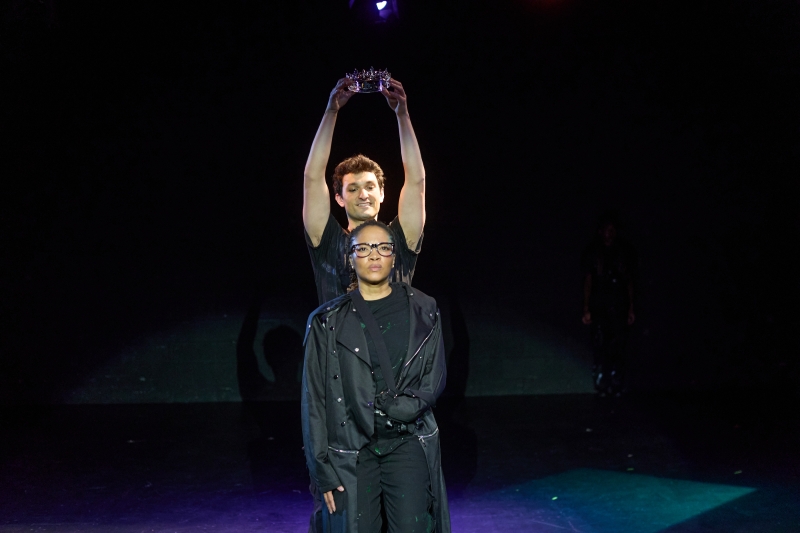

Solomon HaileSelassie’s lighting design is creative and clever, and plays well off of Charlie Van Kirk’s artful costumes – the Margarets’ coats are particularly striking, and the distinct pieces used to identify each character were smartly chosen. Sound Designer Marcus Kyd’s presence is subtle, yet effective, filling the black box theater comfortably with both the play itself as well as delightful Medieval-style covers of modern music that played before and after the show as well as during intermissions. James Finley, as the Fight & Intimacy Choreographer, nearly directs as much as Miller (it is a war play, after all), though the two deftly guide the cast around the sparse stage, convincingly building Margaret’s world and drawing the audience in. This minimalist approach also allows for more audience engagement and creativity, even eliciting a few dark laughs, and bringing in a level of participation – audience members are asked to choose between the Lancasters and the Yorks before entering the theater, assigned seating based on their faction and given the option to wear their loyalty through a sticker or temporary tattoo (designed by Andy Gomez Reyes).

The true highlight of this production, though, is the little, fiercely talented cast. Stephen Kime, who serves as the Chorus and a number of bit roles, has a captivating presence and often adds touches of humor, guiding Margaret’s journey while pointing out what the characters, too close to the action, often miss in their own quests for power. Kime is the perfect vehicle for Miller’s more acerbic commentary, and is the ideal stand-in for the audience itself amidst the onstage power struggles. Kiana Johnson’s regal run as the Duke of York/King Edward IV/King Louis portrays a series of engaging characters and explores the different ways power can manifest: her York is proud, but often brash; while her Edward is perhaps too overconfident in his position, leading to his ultimate downfall; and Louis falls towards the more cautious end of the spectrum. Johnson shows these responses to power, highlighting the range of its impact and the consequences of each, with a thoughtfulness that never quite crosses into self-importance; there’s a joy in her performance that keeps each version safely grounded. Primarily playing the role of Henry VI, Sam Richie contrasts Johnson’s display of confident power with Henry’s own shaky hold on it; rather than playing into “mad king” personas, Richie opts for a more nuanced, burdened portrayal of the king, showing that his weakness stems from his own reluctance to partake in the schemes and mechanisms that have so enthralled everyone around him. There’s a loneliness and resignation in Richie’s performance that lends a layer of sympathy to this king who doesn’t much seem to care to rule. Devin Nikki Thomas immediately steals the show with her portrayals of Joan of Arc and Lady Eleanor, whetting the audience’s appetite for her main role as Richard III – aided by Van Kirk’s top-tier coat and strap ensemble to portray Richard’s rumored deformities, Thomas’ rendition of the hated monarch and his quest for power is undeniably captivating. Her Richard is a villain the audience loves to hate.

The role of Margaret is divided among three actresses: Alyssa Sanders in Act I (who later plays Queen Elizabeth of York), Sara Barker in Act II (who also portrays the Duke of Suffolk and Anne Neville), and Kathleen Akerley in Act III (who plays the Earl of Warwick in the first two acts). The change of performer helps signify the shifts in Margaret’s character as the plot progresses: Sanders’ Margaret is young, hopeful, and ambitious, and the loss of her ally in Suffolk at the end of the act signals a change to the decisive and hardened leader she becomes as she assumes control of the Lancaster family’s cause and forces in Act II, as Barker. When she loses both her son and her crown at the Battle of Tewkesbury at the end of the second Act, the transition is again palpable – the curdling of hope and ambition creates a bitterness that drives Akerley’s Act III Margaret, a version whose only solace is in cursing her foes to a similar fate and watching them share in her defeat. The interactions between the actresses also add a fascinating layer – Sanders and Barker have great chemistry as forbidden lovers in the first act, and watching Sanders bury her heart with Barker’s Suffolk before passing on the role in a gorgeous funeral rite shows Margaret growing from a sheltered woman to a battle-ready monarch. Likewise, a similar ritual at the end of Act II, where Akerley plays Margaret’s dying son, Ned, before assuming the mantle of the titular character, mirrors the shift in her character due to profound loss, though this time it highlights how the loss broke, rather than impelled her. The splintering of the character into these three distinct portrayals is a clever way to show the distinct stages of Margaret’s life and relationships, and tying each transition to the main motivating character was a smart arrangement that was beautifully and emotionally executed.

Miller’s exploration of this formidable queen and Shakespearean presence ends with their own ruminations that launched this production: There was a time when those who waged war were accountable. They celebrated triumphs, suffered defeats, and faced the consequences of their actions while watching their foes experience the same cycle of victory and loss. They had to contend with their actions directly, as Margaret did. Which raises the question: would direct costs change those decisions? They certainly didn’t for Margaret, who died alone, penniless, and resentful, but, perhaps, our leaders can learn from her and her quest for power all the same.

The Margriad, or, The Tragedy of Queen Margaret runs at Avant Bard through March 29th, with evening performances on Thursday – Saturday and matinees on Saturdays & Sundays. Performance run time is approximately two hours and 20 minutes with two 10-minute intermissions. This production contains some depictions of violence, explicit language, and the use of lights that strobe or flash rapidly. Avant Bard offers complimentary tickets for Arlington County middle and high school students (with half-price tickets available for accompanying adults), as well as for federal government employees who were wrongfully terminated by the current administration. Additional discounts are available for senior citizens and veterans, and the theater offers select performances with a “pay-what-you-can” option. Full ticket and discount information, as well as information on accessibility, masked performances, and other theater information can be found on the Avant Bard website.

Photo Credit: DJ Corey Photography

Banner Photo: From left: Stephen Kime, and from bottom: Alyssa Sanders, Sara Barker, Kathleen Akerley

Reader Reviews

Videos