Review Roundup: THE SHARK IS BROKEN Opens On Broadway- See What The Critics Are Saying!

This new play explores what happened when the cameras stopped rolling during the filming of Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster, JAWS.

THE SHARK IS BROKEN officially opens tonight at Broadway's Golden Theatre for a strictly limited 16-week engagement. Read the reviews!

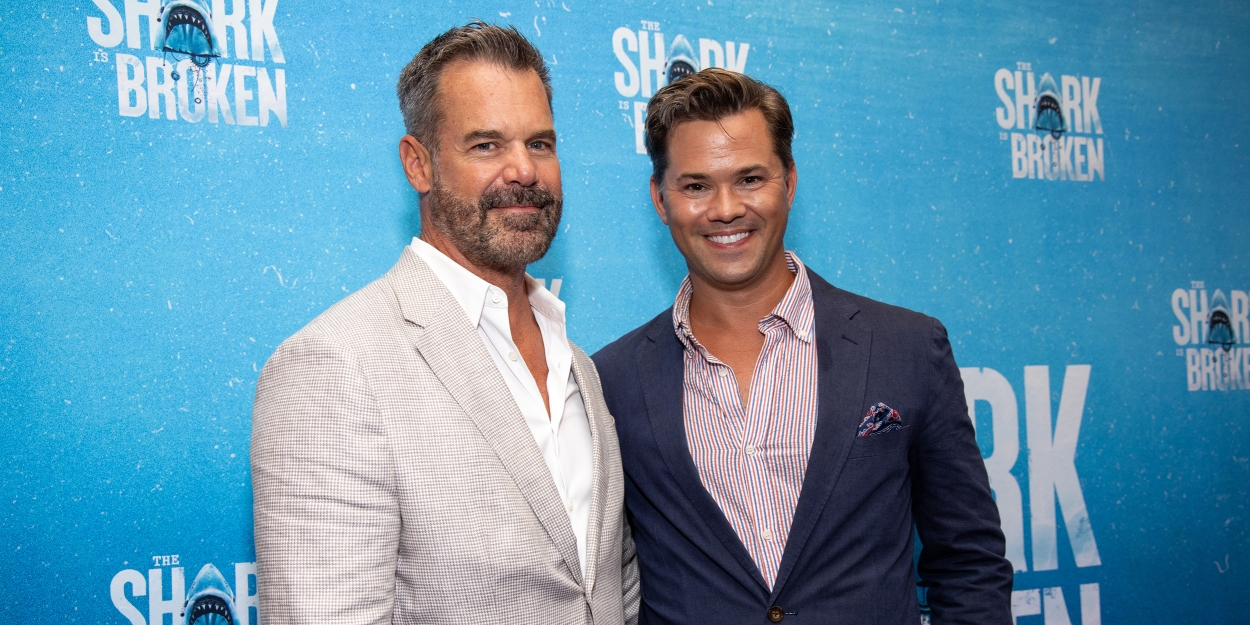

THE SHARK IS BROKEN stars two-time Tony Award nominee Alex Brightman (Beetlejuice, School of Rock) as Richard Dreyfuss, Colin Donnell (Anything Goes, “Chicago Med”) as Roy Scheider, and Ian Shaw who is making his Broadway debut portraying his father Robert Shaw, who played “Quint” in JAWS.

Co-written by Ian Shaw and Joseph Nixon, this new Olivier Award-nominated comedy imagines what happened on board “The Orca” when the cameras stopped rolling during the filming of Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster, JAWS.

FADE IN: The open ocean, 1974. Filming on JAWS is delayed…again. The film’s lead actors—theatre veteran Robert Shaw and young Hollywood hotshots, Richard Dreyfuss and Roy Scheider—are crammed into a too-small boat, entirely at the mercy of foul weather and a faulty mechanical co-star. Alcohol flows, egos collide, and tempers flare on a chaotic voyage that just might lead to cinematic magic…if it doesn’t sink them all.

Directed by Guy Masterson, THE SHARK IS BROKEN has scenic and costume design by Duncan Henderson, lighting design by Jon Clark, sound design and original music by Adam Cork, video design by Nina Dunn, and casting by Jim Carnahan Casting. Rounding out the company of THE SHARK IS BROKEN are understudies Peter Bradbury, Stephen Dexter, and Coby Getzug.

![]() Charles Isherwood, The Wall Street Journal: Slender though it may be, at a crisp 95 minutes it holds one’s attention in no small part because the actors playing their more famous counterparts are so superb, giving performances that perfectly capture the personas, mannerisms and idiosyncrasies of Shaw, Dreyfuss and Scheider, at least as documented in various books and movies about the making of “Jaws.” Yet none of the actors is indulging in mere comic mimicry. All give fully rounded, nuanced performances that give the play a layer of verisimilitude in its more serious moments, as the movie actors—each at a different stage in his career—turn to self-examination and reveal their doubts and demons.

Charles Isherwood, The Wall Street Journal: Slender though it may be, at a crisp 95 minutes it holds one’s attention in no small part because the actors playing their more famous counterparts are so superb, giving performances that perfectly capture the personas, mannerisms and idiosyncrasies of Shaw, Dreyfuss and Scheider, at least as documented in various books and movies about the making of “Jaws.” Yet none of the actors is indulging in mere comic mimicry. All give fully rounded, nuanced performances that give the play a layer of verisimilitude in its more serious moments, as the movie actors—each at a different stage in his career—turn to self-examination and reveal their doubts and demons.

![]() Dalton Ross, Entertainment Weekly: But The Shark Is Broken - directed by Guy Masterson — is far from a maudlin experience. There are also laughs aplenty as the three argue about their billing on the movie poster, discuss the relationship between golf and sperm, break into impromptu song, and engage in all manner of games and bets to pass the time. Those moments ground the characters and work better than when the script goes for the low hanging fruit of actors from the 1970s commenting on the idiocy of sequels (Jaws would have three of them), and how ridiculous it would be to make a movie about outer space (Close Encounters, anyone?) or dinosaurs (hello, Jurassic Park!) Easy jokes like these may get some of the biggest laughs in the room, but feel a bit cheap and take away from the interplay between the characters.

Dalton Ross, Entertainment Weekly: But The Shark Is Broken - directed by Guy Masterson — is far from a maudlin experience. There are also laughs aplenty as the three argue about their billing on the movie poster, discuss the relationship between golf and sperm, break into impromptu song, and engage in all manner of games and bets to pass the time. Those moments ground the characters and work better than when the script goes for the low hanging fruit of actors from the 1970s commenting on the idiocy of sequels (Jaws would have three of them), and how ridiculous it would be to make a movie about outer space (Close Encounters, anyone?) or dinosaurs (hello, Jurassic Park!) Easy jokes like these may get some of the biggest laughs in the room, but feel a bit cheap and take away from the interplay between the characters.

![]() Jesse Green, The New York Times: All of that is faithfully rendered in “The Shark Is Broken,” which opened on Thursday at the Golden Theater, in a production directed by Guy Masterson. There’s a perfect replica of the Orca bobbing prettily on a C.G.I. sea, and costumes minutely matched to the film. (Duncan Henderson is the designer.) Accents, postures, props and hairstyles are fanatically accurate; there’s even a hat-tip (by Adam Cork) to John Williams’s sawing, rasping theme at the start. But these details do not on their own create much dramatic interest. Plots consisting of hurry-up-and-wait rarely do. Were it not for its curious meta-story, the play would be little more than a pleasant diversion: 95 minutes of bloodless, toothless, Hollywood-adjacent dramedy.

Jesse Green, The New York Times: All of that is faithfully rendered in “The Shark Is Broken,” which opened on Thursday at the Golden Theater, in a production directed by Guy Masterson. There’s a perfect replica of the Orca bobbing prettily on a C.G.I. sea, and costumes minutely matched to the film. (Duncan Henderson is the designer.) Accents, postures, props and hairstyles are fanatically accurate; there’s even a hat-tip (by Adam Cork) to John Williams’s sawing, rasping theme at the start. But these details do not on their own create much dramatic interest. Plots consisting of hurry-up-and-wait rarely do. Were it not for its curious meta-story, the play would be little more than a pleasant diversion: 95 minutes of bloodless, toothless, Hollywood-adjacent dramedy.

![]() Jackson McHenry, Vulture: That extra-textural dramatic irony gnaws at The Shark Is Broken, which has less integrity as a play than as a thoroughly researched dress-up presentation for a history-of-film class. Ian Shaw, no great surprise, strongly resembles his father, and Brightman and Donnell have both been made up into ringers for Dreyfuss and Scheider. (Praise to Duncan Henderson’s costumes and to the wigs by Campbell Young Associates.) Everyone is meticulously re-creating those familiar voices — Brightman in particular zips right through Dreyfuss’s manic, cokie rants with gusto — and acting out his character’s well-known on-set habits. But although the actors are raring to go, the staging is cramped, with director Guy Masterson running out of ways to shuffle them around a boat that, yes, we know, is quite claustrophobic. (That’s surely the intent, but it makes the play seem smaller than it should.) More pressingly, the writing, intent on remaining lightly comic and knowing, keeps delivering what is familiar and unchallenging. Donnell, in a nod to Scheider’s love of tanning, strips down in an awkwardly staged moment to sunbathe, drawing titters from the audience, a gesture where fan service and beefcake collide.

Jackson McHenry, Vulture: That extra-textural dramatic irony gnaws at The Shark Is Broken, which has less integrity as a play than as a thoroughly researched dress-up presentation for a history-of-film class. Ian Shaw, no great surprise, strongly resembles his father, and Brightman and Donnell have both been made up into ringers for Dreyfuss and Scheider. (Praise to Duncan Henderson’s costumes and to the wigs by Campbell Young Associates.) Everyone is meticulously re-creating those familiar voices — Brightman in particular zips right through Dreyfuss’s manic, cokie rants with gusto — and acting out his character’s well-known on-set habits. But although the actors are raring to go, the staging is cramped, with director Guy Masterson running out of ways to shuffle them around a boat that, yes, we know, is quite claustrophobic. (That’s surely the intent, but it makes the play seem smaller than it should.) More pressingly, the writing, intent on remaining lightly comic and knowing, keeps delivering what is familiar and unchallenging. Donnell, in a nod to Scheider’s love of tanning, strips down in an awkwardly staged moment to sunbathe, drawing titters from the audience, a gesture where fan service and beefcake collide.

![]() Johnny Oleksinki, The New York Post: The effect of their macho antics, however, is much the same as listening to your drunken friends argue about capitalism at 2 a.m. They keep on yapping and are not getting anywhere, so you zone out.

Big-personality confrontations about who the real star of the movie is — and who’s the better actor — are neither rip-roaring nor very insightful. They start out amusingly petty, and quickly grow repetitive. The draw, though, is Ian Shaw. He is the son of Robert Shaw — the Shakespearean actor who played gruff shark hunter Quint and who died in 1978. Ian plays his dad in the show he co-wrote. So, not coincidentally, he’s the best part of the play directed by Guy Masterson.

Johnny Oleksinki, The New York Post: The effect of their macho antics, however, is much the same as listening to your drunken friends argue about capitalism at 2 a.m. They keep on yapping and are not getting anywhere, so you zone out.

Big-personality confrontations about who the real star of the movie is — and who’s the better actor — are neither rip-roaring nor very insightful. They start out amusingly petty, and quickly grow repetitive. The draw, though, is Ian Shaw. He is the son of Robert Shaw — the Shakespearean actor who played gruff shark hunter Quint and who died in 1978. Ian plays his dad in the show he co-wrote. So, not coincidentally, he’s the best part of the play directed by Guy Masterson.

![]() Greg Evans, Deadline: The problem facing the playwrights is finding a new hook (sorry) in telling this oft-told making-of-a-fish tale. Much of the behind-the-scenes details have been widely known since the 1970s, in part due to the outstanding memoir The Jaws Log by screenwriter Carl Gottlieb. Indeed, the on-set difficulties have become so entrenched in cultural lore that the title of this play needs no explanation or elaboration to reel in audiences. And even though the film cast’s personality clashes are nearly as legendary as the mechanical shark’s short circuits, the play’s authors and performers deliver such nicely detailed characterizations that The Shark Is Broken holds our interest throughout its 95 minutes.

Greg Evans, Deadline: The problem facing the playwrights is finding a new hook (sorry) in telling this oft-told making-of-a-fish tale. Much of the behind-the-scenes details have been widely known since the 1970s, in part due to the outstanding memoir The Jaws Log by screenwriter Carl Gottlieb. Indeed, the on-set difficulties have become so entrenched in cultural lore that the title of this play needs no explanation or elaboration to reel in audiences. And even though the film cast’s personality clashes are nearly as legendary as the mechanical shark’s short circuits, the play’s authors and performers deliver such nicely detailed characterizations that The Shark Is Broken holds our interest throughout its 95 minutes.

![]() Chris Jones, The New York Daily News: “What psychological insights into Shaw might we be offered?” I wondered on the way into the theater, “What deep-dive revelations await from a creative act that would appear to be both hubristic and profoundly courageous?” The younger Shaw must have had a window into his father that would have eluded most biographers. Or so you’d think. Alas, the show doesn’t deliver much at all. Not only is the low-stakes script dull and pedestrian, but the characters change not at all, despite the premise of three wild men sitting in a boat, waiting not for Godot but sharks and Spielberg. “The Shark is Broken” had its origins at the Edinburgh Festival, and in that context, it no doubt was a good campy laugh, especially for an audience that had followed Shaw’s pre-gaming example. But it makes for thin Broadway gruel, alas, with a 90-minute running time, a straight-up POV, and a series of behind-the-camera recreations of a situation that already has been much dissected and discussed.

Chris Jones, The New York Daily News: “What psychological insights into Shaw might we be offered?” I wondered on the way into the theater, “What deep-dive revelations await from a creative act that would appear to be both hubristic and profoundly courageous?” The younger Shaw must have had a window into his father that would have eluded most biographers. Or so you’d think. Alas, the show doesn’t deliver much at all. Not only is the low-stakes script dull and pedestrian, but the characters change not at all, despite the premise of three wild men sitting in a boat, waiting not for Godot but sharks and Spielberg. “The Shark is Broken” had its origins at the Edinburgh Festival, and in that context, it no doubt was a good campy laugh, especially for an audience that had followed Shaw’s pre-gaming example. But it makes for thin Broadway gruel, alas, with a 90-minute running time, a straight-up POV, and a series of behind-the-camera recreations of a situation that already has been much dissected and discussed.

![]() Adam Feldman, Time Out New York: If not for our ongoing fascination with Jaws, The Shark Is Broken would be of limited interest: three men in a boat reading newspaper articles (“NIXON RESIGNS”), reminiscing about their childhoods, bickering about Hollywood and drinking a whole lot more than they should. But since the movie remains a cultural touchstone, the play makes for pleasant entertainment. Director Guy Masterson does an admirable job of finding tension and variety in a very low-stakes situation; scenic designer Duncan Henderson’s cross-section of a boat is effectively nested in Nina Dunn’s video design, a curving backdrop of water and sky.

Adam Feldman, Time Out New York: If not for our ongoing fascination with Jaws, The Shark Is Broken would be of limited interest: three men in a boat reading newspaper articles (“NIXON RESIGNS”), reminiscing about their childhoods, bickering about Hollywood and drinking a whole lot more than they should. But since the movie remains a cultural touchstone, the play makes for pleasant entertainment. Director Guy Masterson does an admirable job of finding tension and variety in a very low-stakes situation; scenic designer Duncan Henderson’s cross-section of a boat is effectively nested in Nina Dunn’s video design, a curving backdrop of water and sky.

![]() Tim Teeman, The Daily Beast: “Do you really think people are going to be talking about this in fifty years?” he adds a moment later, showing his crystal ball is just as faulty as it is functioning. The final shot soon-to-be-completed, the men know giddily that freedom will soon be theirs. But what they don’t know is that Jaws will go on to become the cultural totem we know it as today—and it is in the humorous and profound gap of past and present, known and unknown, and ignorance and wisdom that The Shark Is Broken wittily excels not just as a clever time capsule, but as an examination of male bonding and competitiveness, ego, frailty, fame, and film-making. Which is to say: you don’t miss the shark for one second.

Tim Teeman, The Daily Beast: “Do you really think people are going to be talking about this in fifty years?” he adds a moment later, showing his crystal ball is just as faulty as it is functioning. The final shot soon-to-be-completed, the men know giddily that freedom will soon be theirs. But what they don’t know is that Jaws will go on to become the cultural totem we know it as today—and it is in the humorous and profound gap of past and present, known and unknown, and ignorance and wisdom that The Shark Is Broken wittily excels not just as a clever time capsule, but as an examination of male bonding and competitiveness, ego, frailty, fame, and film-making. Which is to say: you don’t miss the shark for one second.

![]() Robert Hofler, The Wrap: Robert Shaw’s portrayal of Quint in “Jaws” remains one of the most grating performances ever put on celluloid. Ian Shaw imitates his father’s every grimace and vocal mannerism, delivering one of the most grating performances ever put on stage. Meanwhile, Brightman and Donnell don’t appear to be playing Dreyfuss and Scheider, but rather the characters Hooper and Brody as portrayed by those actors in the film. “Shark” is written so that each actor gets his solo moment to unload on Dad, blow up in a dramatic fashion and show off his thespian chops. Guy Masterson’s blunt direction does nothing to mitigate these over-the-top acting exercises.

Robert Hofler, The Wrap: Robert Shaw’s portrayal of Quint in “Jaws” remains one of the most grating performances ever put on celluloid. Ian Shaw imitates his father’s every grimace and vocal mannerism, delivering one of the most grating performances ever put on stage. Meanwhile, Brightman and Donnell don’t appear to be playing Dreyfuss and Scheider, but rather the characters Hooper and Brody as portrayed by those actors in the film. “Shark” is written so that each actor gets his solo moment to unload on Dad, blow up in a dramatic fashion and show off his thespian chops. Guy Masterson’s blunt direction does nothing to mitigate these over-the-top acting exercises.

![]() Steven Suskin, New York Stage Review: The younger Mr. Shaw, who is now older than his father was when he died in 1978 at the age of 51, has stepped into his father’s deck shoes. He is joined by actors Colin Donnell (partner to Sutton Foster in both Anything Goes and Violet), who has the mannerisms of the late Scheider down pat, and Alex Brightman (of School of Rock and Beetlejuice), who limns a supremely sharp sketch of an impossibly but believably annoying Dreyfuss. The two American actors, by now quite familiar for their Broadway musical appearances, offer exceptionally diverting caricatures.

Steven Suskin, New York Stage Review: The younger Mr. Shaw, who is now older than his father was when he died in 1978 at the age of 51, has stepped into his father’s deck shoes. He is joined by actors Colin Donnell (partner to Sutton Foster in both Anything Goes and Violet), who has the mannerisms of the late Scheider down pat, and Alex Brightman (of School of Rock and Beetlejuice), who limns a supremely sharp sketch of an impossibly but believably annoying Dreyfuss. The two American actors, by now quite familiar for their Broadway musical appearances, offer exceptionally diverting caricatures.

![]() Bob Verini, New York Stage Review: In the end, though, the comfort that The Shark Is Broken brings, and it truly is a most enjoyable 95 minutes, stems from the canny way in which it channels Jaws itself. The play’s version of Robert Shaw, when you come right down to it, is Peter Quint, the grizzled veteran baiting and blasting the young whippersnapper whom you can call Dreyfuss or Matt Hooper, it’s all the same. Meanwhile bemused, decent Roy “Chief Brody” Scheider attempts to make peace between mercurial shipmates as he decides on the next fateful phase of his career. Watching The Shark Is Broken, then, is not unlike diving into a boatload of outtakes from a beloved classic. If you’re anything like me, you eat it up like it’s popcorn.

Bob Verini, New York Stage Review: In the end, though, the comfort that The Shark Is Broken brings, and it truly is a most enjoyable 95 minutes, stems from the canny way in which it channels Jaws itself. The play’s version of Robert Shaw, when you come right down to it, is Peter Quint, the grizzled veteran baiting and blasting the young whippersnapper whom you can call Dreyfuss or Matt Hooper, it’s all the same. Meanwhile bemused, decent Roy “Chief Brody” Scheider attempts to make peace between mercurial shipmates as he decides on the next fateful phase of his career. Watching The Shark Is Broken, then, is not unlike diving into a boatload of outtakes from a beloved classic. If you’re anything like me, you eat it up like it’s popcorn.

![]() David Cote, Observer: Need I add that Jaws will probably be admired for another 50 years, whereas The Shark Is Broken sinks from memory not long after you exit the Golden Theatre? As you sit watching three skilled and likable actors do celebrity impressions, there are decent punch lines, visual treats, even a poignant moment or two of harpooned masculinity. But this behind-the-scenes buddy drama—which swam from the Edinburgh Fringe to London’s West End and finally washed up on Broadway—is a handful of chum in a very big sea.

David Cote, Observer: Need I add that Jaws will probably be admired for another 50 years, whereas The Shark Is Broken sinks from memory not long after you exit the Golden Theatre? As you sit watching three skilled and likable actors do celebrity impressions, there are decent punch lines, visual treats, even a poignant moment or two of harpooned masculinity. But this behind-the-scenes buddy drama—which swam from the Edinburgh Fringe to London’s West End and finally washed up on Broadway—is a handful of chum in a very big sea.

![]() Howard Miller, Talkin' Broadway: Eventually, we get to the last day of filming and the final farewells. Not surprisingly, Scheider proffers his hand to the other two: 'I gotta say, I feel kind of sad. It's been a pleasure, gentlemen.' And true to form, Shaw and Dreyfuss say goodbye by trading sarcastic barbs. I hate to carp, but while Jaws may be the ultimate fish story, The Shark Is Broken flounders to the end, with neither an engaging hook nor a line of compelling dialog to keep it afloat.

Howard Miller, Talkin' Broadway: Eventually, we get to the last day of filming and the final farewells. Not surprisingly, Scheider proffers his hand to the other two: 'I gotta say, I feel kind of sad. It's been a pleasure, gentlemen.' And true to form, Shaw and Dreyfuss say goodbye by trading sarcastic barbs. I hate to carp, but while Jaws may be the ultimate fish story, The Shark Is Broken flounders to the end, with neither an engaging hook nor a line of compelling dialog to keep it afloat.

![]() Jonathan Mandell, New York Theater: I suppose if you knew nothing about Steven Spielberg or “Jaws” or the blockbuster’s three stars — Robert Shaw , Roy Scheider and Richard Dreyfuss – you might still be able to appreciate “The Shark Is Broken” as a kind of Beckett-light pop play about three characters who spend most of their time waiting for something to happen. But it’s the reflected cinematic glory in this modest stage comedy that surely explains why, four years after its month-long run at the Edinburgh Fringe festival, it has opened tonight on Broadway. The production is not an embarrassment. All three actors give uncanny impersonations that sometimes shade into nuanced portraits. The design team does an impressive job with a subtly animated, ever-changing backdrop for the fishing boat of rolling sea and cloud-streaked sky.

Jonathan Mandell, New York Theater: I suppose if you knew nothing about Steven Spielberg or “Jaws” or the blockbuster’s three stars — Robert Shaw , Roy Scheider and Richard Dreyfuss – you might still be able to appreciate “The Shark Is Broken” as a kind of Beckett-light pop play about three characters who spend most of their time waiting for something to happen. But it’s the reflected cinematic glory in this modest stage comedy that surely explains why, four years after its month-long run at the Edinburgh Fringe festival, it has opened tonight on Broadway. The production is not an embarrassment. All three actors give uncanny impersonations that sometimes shade into nuanced portraits. The design team does an impressive job with a subtly animated, ever-changing backdrop for the fishing boat of rolling sea and cloud-streaked sky.

![]() Kristy Puchko, Mashable: Incredibly, The Shark Is Broken aspires to similar depths despite its comedic trappings. On its surface, the 95-minute play is about the frustrations, petty rivalries, and not-so-secret vices that Scheider, Dreyfuss, and Shaw may have gotten up to while waiting for cameras to roll on Jaws. But in between jokes, fan service, and some tasty movie trivia, a story of fathers, sons, mortality, and legacy begins to rise. Fittingly, the late Robert Shaw's son Ian Shaw, who visited the Jaws set when he was just a child, is the play's co-writer and co-star. He nimbly steps into the soggy shoes of his father, lending an undercurrent of poignancy to the broader comedic strokes.

Kristy Puchko, Mashable: Incredibly, The Shark Is Broken aspires to similar depths despite its comedic trappings. On its surface, the 95-minute play is about the frustrations, petty rivalries, and not-so-secret vices that Scheider, Dreyfuss, and Shaw may have gotten up to while waiting for cameras to roll on Jaws. But in between jokes, fan service, and some tasty movie trivia, a story of fathers, sons, mortality, and legacy begins to rise. Fittingly, the late Robert Shaw's son Ian Shaw, who visited the Jaws set when he was just a child, is the play's co-writer and co-star. He nimbly steps into the soggy shoes of his father, lending an undercurrent of poignancy to the broader comedic strokes.

![]() Joe Dziemianowicz, New York Theatre Guide: Jaws was action-packed. The Shark Is Broken is all talk, and a pattern emerges. Shaw and Dreyfuss clash. Scheider referees. It gets repetitive over the 95-minute run time. On the plus side, there are moments when the warring trio clicks and a sort of camaraderie shines through. Plus, the co-authors seasoned the script with laughs. Some humor comes with a knowing wink. There’s a comment about Richard Nixon, who resigned the presidency during the film shoot, being the most immoral president ever. There’s scoffing about the unseen Spielberg, whose next movie will be about, of all things, aliens. And Scheider vows he’ll never do a Jaws sequel. Never say never. Director Guy Masterson guides the evocative production and fine-tuned cast. In the least showy part, Donnell (Anything Goes, Chicago Med) lends ballast as the even-keeled Scheider. Brightman, a Tony nominee for School of Rock and Beetlejuice the Musical, proves to be a master of mimicry and cranks the nerdy, needy intensity to 11 as Dreyfuss.

Ian Shaw is a dead ringer for his dad and is fun to watch simply for that reason. The play is, ultimately, a valentine to Robert Shaw. The filming of Quint’s chilling monologue about the atomic bomb in Jaws, a speech he was too drunk to get right in the first take, concludes the play on serious note. Occasionally, between “action” and “cut,” there’s smooth sailing. As it bites into movie history, The Shark Is Broken makes for a diversion worth sea-ing.

Joe Dziemianowicz, New York Theatre Guide: Jaws was action-packed. The Shark Is Broken is all talk, and a pattern emerges. Shaw and Dreyfuss clash. Scheider referees. It gets repetitive over the 95-minute run time. On the plus side, there are moments when the warring trio clicks and a sort of camaraderie shines through. Plus, the co-authors seasoned the script with laughs. Some humor comes with a knowing wink. There’s a comment about Richard Nixon, who resigned the presidency during the film shoot, being the most immoral president ever. There’s scoffing about the unseen Spielberg, whose next movie will be about, of all things, aliens. And Scheider vows he’ll never do a Jaws sequel. Never say never. Director Guy Masterson guides the evocative production and fine-tuned cast. In the least showy part, Donnell (Anything Goes, Chicago Med) lends ballast as the even-keeled Scheider. Brightman, a Tony nominee for School of Rock and Beetlejuice the Musical, proves to be a master of mimicry and cranks the nerdy, needy intensity to 11 as Dreyfuss.

Ian Shaw is a dead ringer for his dad and is fun to watch simply for that reason. The play is, ultimately, a valentine to Robert Shaw. The filming of Quint’s chilling monologue about the atomic bomb in Jaws, a speech he was too drunk to get right in the first take, concludes the play on serious note. Occasionally, between “action” and “cut,” there’s smooth sailing. As it bites into movie history, The Shark Is Broken makes for a diversion worth sea-ing.

![]() Juan A. Ramirez, Theatrely: The problem is that I’ve just essentially described the plot of the film itself, which makes watching this somewhat of an exercise in cinematic foreplay: I couldn’t wait to go home and watch Spielberg’s masterpiece. Here, art imitating life imitating art is a hindrance. The performances are great, Duncan Henderson’s recreation of the Orca fishing boat visually compelling, and Guy Masterson’s direction is lively enough. But, like the shark itself, the play’s essential functions scarcely work — save for the few scenes in which the three men, caught in an epochal shift in acting and celebrity, wax poetic about the fall of fathers, the impotence of sons, and the rolling tides of art. That’s when the play finds its bite. Otherwise, with its slavish recreations of the production’s details and Brightman’s (as required) over-hamming, it feels like an SNL skit waiting for its punchline.

Juan A. Ramirez, Theatrely: The problem is that I’ve just essentially described the plot of the film itself, which makes watching this somewhat of an exercise in cinematic foreplay: I couldn’t wait to go home and watch Spielberg’s masterpiece. Here, art imitating life imitating art is a hindrance. The performances are great, Duncan Henderson’s recreation of the Orca fishing boat visually compelling, and Guy Masterson’s direction is lively enough. But, like the shark itself, the play’s essential functions scarcely work — save for the few scenes in which the three men, caught in an epochal shift in acting and celebrity, wax poetic about the fall of fathers, the impotence of sons, and the rolling tides of art. That’s when the play finds its bite. Otherwise, with its slavish recreations of the production’s details and Brightman’s (as required) over-hamming, it feels like an SNL skit waiting for its punchline.

![]() Matthew Wexler, Queerty: The Shark is Broken’s scenic design is packed with memorabilia from the original film, including a floatation barrel used to track the fictional predator, but the real memories pay homage to Robert Shaw’s complicated life as an artist struggling with addiction. In preparation for the role, son Ian reviewed a drinking diary the actor logged during the 1970s. “It gave me a baseline about how he felt about his alcoholism,” Shaw told the New York Times. “He had tried to quit and couldn’t do it. He wanted to concentrate on his writing and it was interfering with that.” Those glimpses are more harrowing than any fake shark could muster.

Matthew Wexler, Queerty: The Shark is Broken’s scenic design is packed with memorabilia from the original film, including a floatation barrel used to track the fictional predator, but the real memories pay homage to Robert Shaw’s complicated life as an artist struggling with addiction. In preparation for the role, son Ian reviewed a drinking diary the actor logged during the 1970s. “It gave me a baseline about how he felt about his alcoholism,” Shaw told the New York Times. “He had tried to quit and couldn’t do it. He wanted to concentrate on his writing and it was interfering with that.” Those glimpses are more harrowing than any fake shark could muster.

Average Rating: 58.9%

- To read more reviews, click here!

- Discuss the show on the BroadwayWorld Forum

Reader Reviews

Powered by

|

Videos