Review: DEATH OF A SALESMAN at Crown Theatre

Arthur Miller classic shows just why it endures long past its setting

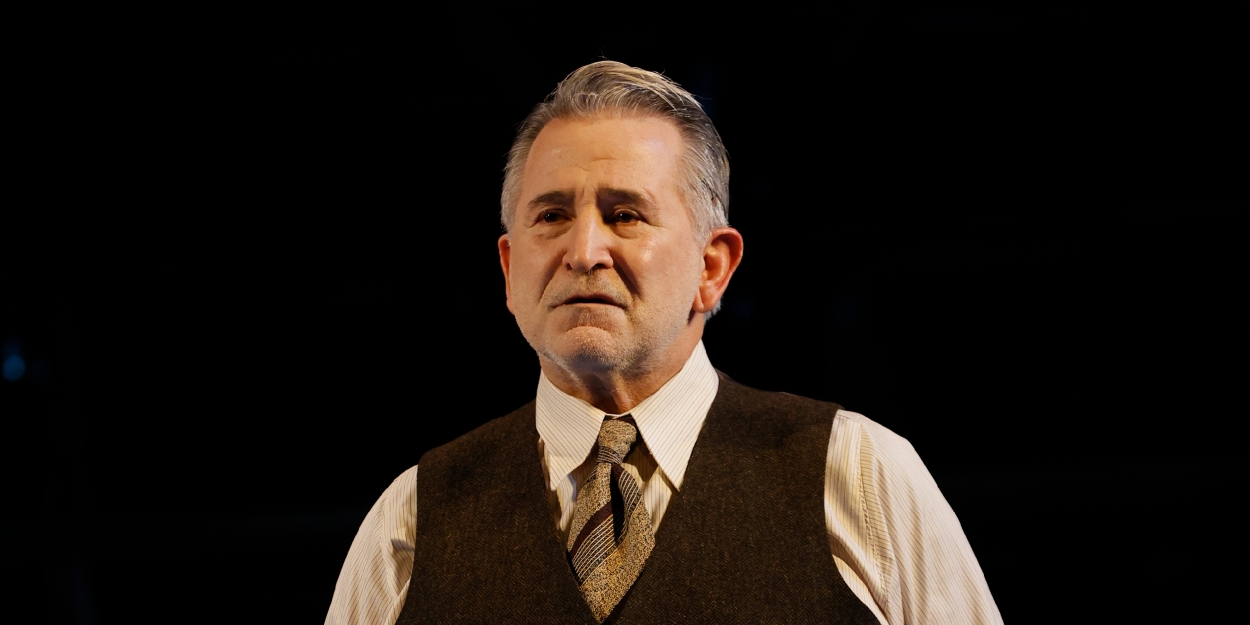

It may be difficult to explain how a play so firmly set 75 years and half a world away can find success today, but DEATH OF A SALESMAN does just that. The play is brought to life by a single set and a brilliant cast who relentlessly hit with their performances, led by a simply outstanding Anthony LaPaglia. There is an air of enduring relevance to the play, and the many qualities of this performance will ensure it stays with you for a long time.

DEATH OF A SALESMAN is rooted deeply in the time it is set. The American Dream- a term itself only coined in 1931- was, in the eyes of playwright Arthur Miller, dead. The ideals of the roaring 20s met an abrupt end in 1929’s Great Depression, and the country had barely dragged itself up to its knees before it found itself inexorably bound to World War II. By 1949, when the play was written, Arthur Miller was already intimately familiar with both the highest highs one could dream of, and the lowest lows. He knew countless people reaching the end of their tethers, and he portrayed them singularly in Willy Loman. Miller himself would unlikely have imagined his play written in anger at that specific time would still find relevance going forward, and yet, even in 2024, there is an inescapable and poignant connection to now.

Anthony LaPaglia stars as Willy Loman, the titular salesman and the central focus of the beleaguered characters. LaPaglia is simply outstanding, and whilst he may be well known to Australians for his many movie performances, his work onstage persona seems to hit harder. LaPaglia carries his character with an unmistakeable frailty, dragging himself along and wearing himself out frequently. The unavoidable conclusion is that someone like Loman is quite unable to work, and yet he has crafted his own identity so tightly to his work that he is unable to separate the two. With not much else altered to make the bring DEATH OF A SALESMAN to modern times, the balance of the cast speak with strong Brooklyn accents, yet LaPaglia gives his character a less sharp, more central New York accent, which means that (by no accident I’m sure) Loman’s diatribes hark to a contemporary American prone to exaggerate and paint fantastical ideals rather than deal with reality. Anthony LaPaglia’s Loman doesn’t dominate the stage but pretends like he ought to, and when portrayed so genuine and raw, it is impossible to not see, as Arthur Miller intended, a hefty dose of normal person in the main character.

As the long suffering Linda Loman is the inimitable Alison Whyte. Whyte’s portrayal of the housewife forced to pick up the pieces of a crumbling family unit and desperately try to keep them together is plain for the audience to see, with each carefully crafter line and look delivered to full effect. Whyte’s genius is her ability to avoid many of the mid-century housewife tropes. At no point is her character ignorant to what is happening around her, and in fact her struggle is knowing exactly what is going on within her family and fighting it anyway.

As the man Willy always wanted to be is Anthony Phelan as Ben Loman. Ben is a man whose life was full of adventure and money, drifting in and out of Willy’s memories throughout the narrative to remind Willy of what he could have had. Anthony Phelan’s wise yet distant voice fits the part perfectly, and his aloofness to the plight of his brother and family uses just one character to paint the picture of Willy’s family during his own upbringing in the way only a very talented actor can.

As Willy’s son Biff is Josh Helman, who perfectly and tragically portrays the catalyst for the whole family having to confront what and who they really are. As a football star sand the one on whom the family’s fortunes rely as the play goes on, Helman brings the vulnerability and weakness to the fore, and whilst his story is tied to the plot, the steady march towards Biff having to admit he can’t be who his father wants him to be is painted in stunning depth by Josh Helman. As Harold ‘Happy’ Loman is Ben O’Toole. O’Toole wonderfully shows why his character is nicknamed happy, beginning as a part of the ideal unit but decaying to show that Happy is yet another character blissfully ignorant to the reality of life .

As the ever-loving neighbour Charley is Marco Chiappi. Chiappi has a difficult task that he meets with aplomb, on one hand being the successful neighbour to heavily contrast with Willy’s life, but also bringing the sparse parts of humour the narrative allows. Chiappi’s character refuses to be worn down by Willy’s persistent refusal to accept a job as much as he needs it, as well as the fact Willy is almost never kind to his kindly neighbour. The genuine love and warmth the character meets this with will bring a smile to your face. As Charley’s son Bernard is is Tom Stokes. Bernard begins as the archetypal post-war nerd, himself trying to keep the Loman’s together when they seem to refuse to do it themselves. Bernard grows and becomes successful- the only actual success we ever see in the show- and indeed it is his pressing Willy for answers as to how the family did fall apart that begins Willy’s descent into sadness and having to confront life. Stokes’ delivery of this critical scene illustrates the dynamic between the two perfectly whilst also highlighting just how different things are for the neighbouring families.

Dale Ferguson’s set is unchanging throughout the show, showing the bleachers at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field, which in the narrative is the scene of what should have been the Loman family’s greatest triumph but instead serves as the point where everything began to go wrong. Whilst the singular scene doesn’t quite fit into the places it’s meant to become, the imagery is striking; upon the bleachers sit all of the people who form a part of Willy’s life, and they all at various points descend to spend time with him before leaving him and ascending from his mind. Neil Armfield’s expertly uses the front of stage as a blank canvas to illustrate the many scenes of the play, and he perfectly utilises each characters strengths to paint the full picture. Sophie Woodward (co-designing with Dale Ferguson) makes costumes that add to each character perfectly and almost alone illustrate the time in which the play is set.

At the risk of spoiling the show (if the title hans't already), DEATH OF A SALESMAN is not a happy show. No character triumphs above, and there is no uplifting rebound from the despair of the finale. Indeed, the post-show buzz that I love to revel in and will often use as a gauge of an audience’s enjoyment of a show is almost non-existent. This shows, however, just how thoroughly and firmly the cast pull you in, and how they all portray so perfectly the family scene. The way Willy is aloof to his actual situation, how Linda desperately tries to keep the family together in the face of everything, how Biff thinks he can still pretend to be someone else and how Happy removes himself from the family set as it suits all sound almost non-sensical, and yet the cast illustrate it in a way that makes it all seem perfectly normal. Much of the play's themes and Arthur Miller’s beliefs only becoming apparent when one is given time to reflect on it, as the presentation of it firmly ensures that you feel Willy is the thoroughly regular person Miller wanted to show him as. Overall, DEATH OF A SALESMAN is the art of theatre at its finest, with the parts brought together exquisitely to force you to think about where you are, but to also consider where other people are.

DEATH OF A SALESMAN is at Crown Theatre until August 29th. Tickets and more information from Death of a Salesman Australia.

Pictures thanks to Jeff Busby.

Reader Reviews

Videos