Review Roundup: JOB Opens On Broadway

Following two extended, sold-out downtown engagements, the hit psychological thriller JOB moves to Broadway for 10 weeks only.

The new play JOB on Broadway opens on Broadway tonight! Read the reviews!

Following two extended, sold-out downtown engagements, the hit psychological thriller JOB moves to Broadway for 10 weeks only.

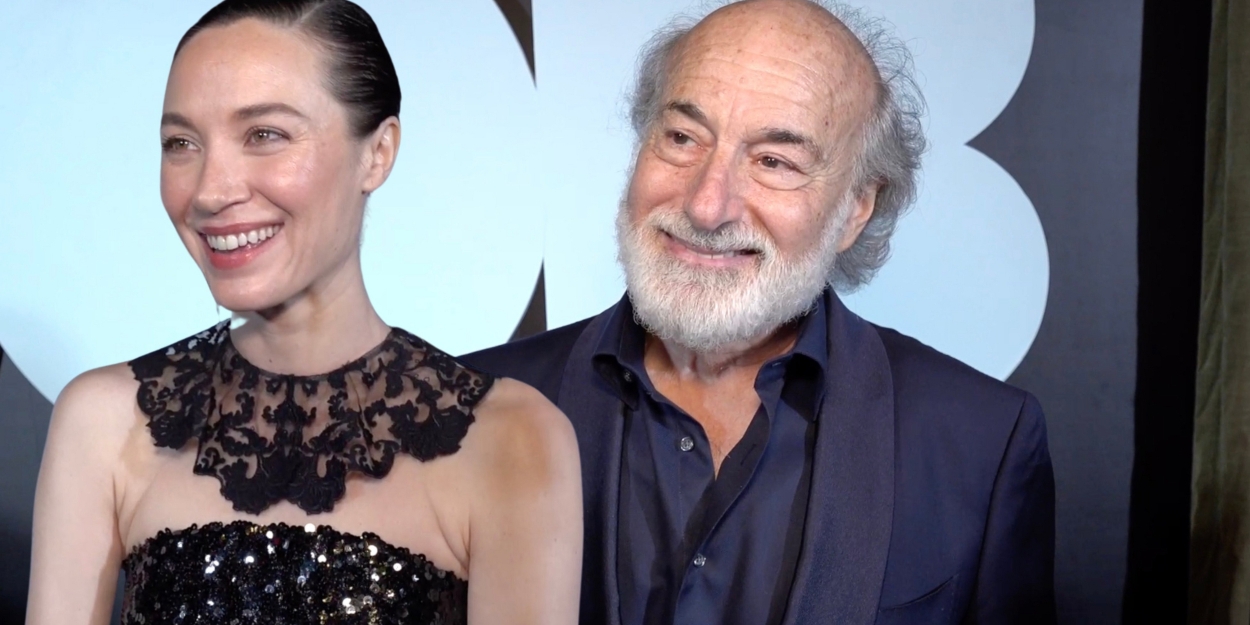

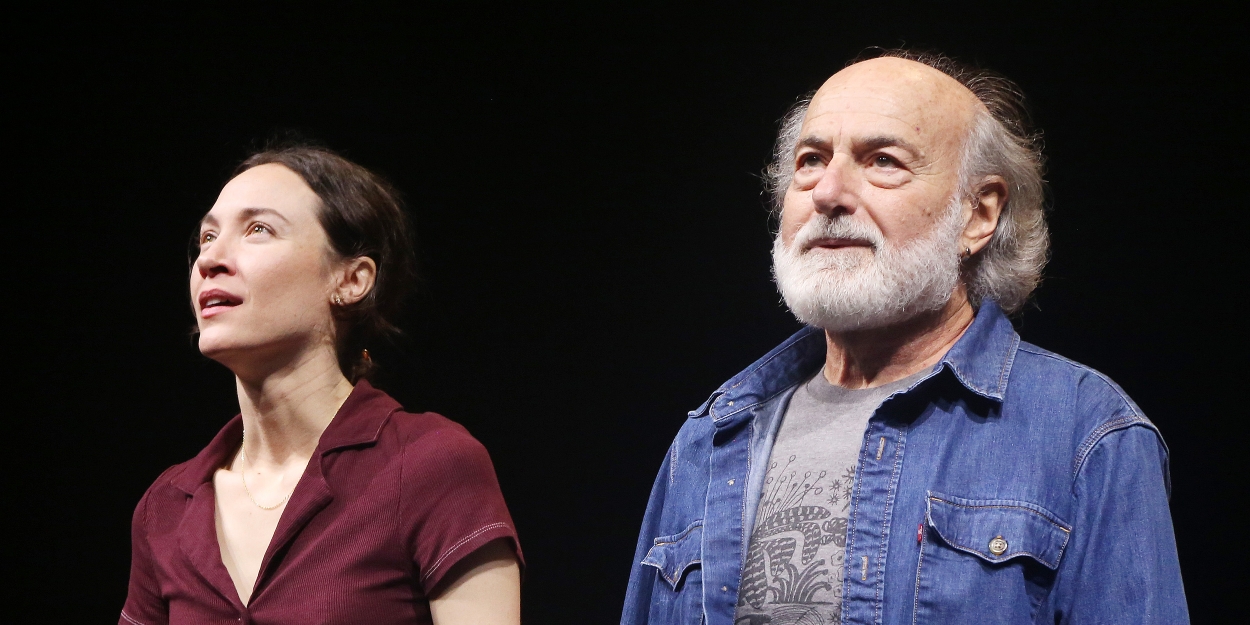

After being placed on leave following a viral incident, Jane would do anything to return to her Big Tech-company job. But as the therapist who needs to authorize it, Loyd suspects her work might be doing more harm than good. With two not-to-be-missed performances from Tony Award nominee Peter Friedman (Ragtime, “Succession”) and Sydney Lemmon (Tár, “Fear the Walking Dead”), “don't be alarmed if you catch yourself holding your breath throughout the entire show” (Time Out New York).

The JOB creative team also features scenic design by Scott Penner, costume design by Michelle J. Li, lighting design by Mextly Couzin, sound design by Cody Spencer, and original music by Devonté Hynes. Rachel A. Zucker will serve as Production Stage Manager while ShowTown Theatricals/Samuel Dallas will serve as the General Manager. Hannah Getts serves as dramaturg. The understudies for JOB are Jeff Still (Loyd) and Arianna Gayle Stucki (Jane).

![]() Jesse Green, The New York Times: Though cleverly accomplished, the shift, as Jane turns the tables on Loyd’s supposed probity, makes “Job” feel even more manipulative than other therapy-based psychological thrillers. By comparison, “The Patient,” the FX series starring Steve Carell as a psychiatrist held hostage, seems like a model of earned dramatic tension. The tension of “Job” feels merely gratuitous.

Jesse Green, The New York Times: Though cleverly accomplished, the shift, as Jane turns the tables on Loyd’s supposed probity, makes “Job” feel even more manipulative than other therapy-based psychological thrillers. By comparison, “The Patient,” the FX series starring Steve Carell as a psychiatrist held hostage, seems like a model of earned dramatic tension. The tension of “Job” feels merely gratuitous.

![]() Jackson McHenry, Vulture: The first time I saw the play, crammed like a sardine right up near the performers at the SoHo Playhouse, the final moments left me with a sickly feeling like the space had filled with poison gas. I’m all for feel-bad theater, but if it’s not precisely concocted, you quickly develop an immunity. A few days after seeing Job then, the poison had passed through me, and I found myself not thinking much about the drama at all. Seeing Job again on Broadway, I didn’t experience the same queasiness when the twist arrived. Maybe the experience suffered because I didn’t have the same physical proximity to the performers. But I also sensed that the play, like a particular kind of internet edgelord, was throwing out shock value to protect itself from having to dig deeper.

Jackson McHenry, Vulture: The first time I saw the play, crammed like a sardine right up near the performers at the SoHo Playhouse, the final moments left me with a sickly feeling like the space had filled with poison gas. I’m all for feel-bad theater, but if it’s not precisely concocted, you quickly develop an immunity. A few days after seeing Job then, the poison had passed through me, and I found myself not thinking much about the drama at all. Seeing Job again on Broadway, I didn’t experience the same queasiness when the twist arrived. Maybe the experience suffered because I didn’t have the same physical proximity to the performers. But I also sensed that the play, like a particular kind of internet edgelord, was throwing out shock value to protect itself from having to dig deeper.

![]() Adrian Horton, The Guardian: It’s muscle-tensing and entertaining, particularly in the play’s middle stretch, to watch a meeting of two differently melted minds. And satisfying when Loyd pokes at Jane’s hypocrisies and delusions, her conviction that she’s nothing and also an online martyr – “It’s a privilege to suffer as much as I do,” she says. Still, Friedlich’s line-by-line writing is shrewd enough to convey Jane’s internal hell of self-reflective mirrors, her spiral of judgment to nowhere. Job is, for the most part, a tonal highwire act that wisely keeps to a taut 80 minutes. Or perhaps the more accurate metaphor is trapeze – swinging wildly between farce, zeitgeist-y drama and thriller. Somehow, it lands most of the tricks, including a turn toward the pitch-black in the final act, which ends just before it runs this tight battle of wills and expertise off the rails. Job smartly knows when to log off; there may be no grand messages (and thank God), but this is one of the more insightful internet spirals.

Adrian Horton, The Guardian: It’s muscle-tensing and entertaining, particularly in the play’s middle stretch, to watch a meeting of two differently melted minds. And satisfying when Loyd pokes at Jane’s hypocrisies and delusions, her conviction that she’s nothing and also an online martyr – “It’s a privilege to suffer as much as I do,” she says. Still, Friedlich’s line-by-line writing is shrewd enough to convey Jane’s internal hell of self-reflective mirrors, her spiral of judgment to nowhere. Job is, for the most part, a tonal highwire act that wisely keeps to a taut 80 minutes. Or perhaps the more accurate metaphor is trapeze – swinging wildly between farce, zeitgeist-y drama and thriller. Somehow, it lands most of the tricks, including a turn toward the pitch-black in the final act, which ends just before it runs this tight battle of wills and expertise off the rails. Job smartly knows when to log off; there may be no grand messages (and thank God), but this is one of the more insightful internet spirals.

![]() Frank Scheck, New York Stage Review: For all the effective stagecraft on display, however, Job (even the title, which many people will assume refers to the Old Testament book, is deliberately confusing) mainly smacks of gimmickry. It’s a psychological thriller that relies too heavily on cheap thrills.

Frank Scheck, New York Stage Review: For all the effective stagecraft on display, however, Job (even the title, which many people will assume refers to the Old Testament book, is deliberately confusing) mainly smacks of gimmickry. It’s a psychological thriller that relies too heavily on cheap thrills.

![]() Melissa Rose Bernardo, New York Stage Review: There’s an intriguing push-pull to Friedlich’s script: Jane needs Loyd to give her the all-clear; at the same time, this overachieving zillennial techie clearly resents needing the approval of some Boomer with an earring who probably couldn’t program an Apple Watch. Lemmon and Friedman (Succession alum alert!), who have been with Job from the start, are terrific, especially in the drama’s most emotionally combative moments. But things go awry after a late-in-the-game twist that pushes the bounds of plausibility attempts (unsuccessfully) to move the play into psychological thriller territory.

Melissa Rose Bernardo, New York Stage Review: There’s an intriguing push-pull to Friedlich’s script: Jane needs Loyd to give her the all-clear; at the same time, this overachieving zillennial techie clearly resents needing the approval of some Boomer with an earring who probably couldn’t program an Apple Watch. Lemmon and Friedman (Succession alum alert!), who have been with Job from the start, are terrific, especially in the drama’s most emotionally combative moments. But things go awry after a late-in-the-game twist that pushes the bounds of plausibility attempts (unsuccessfully) to move the play into psychological thriller territory.

![]() Matt Windman, amNY: Regretfully, I did not see “Job” during its earlier runs, and I suspect that it was probably more exciting to see it in a more intimate downtown space. On Broadway, the production (as directed by Michael Herwitz) looks empty and the play feels underwritten. It dumps compelling societal concerns upon us, leaves them unexplored, and relies structurally on an uninspired starting point (i.e. confessing to a therapist) and gimmicks.

Matt Windman, amNY: Regretfully, I did not see “Job” during its earlier runs, and I suspect that it was probably more exciting to see it in a more intimate downtown space. On Broadway, the production (as directed by Michael Herwitz) looks empty and the play feels underwritten. It dumps compelling societal concerns upon us, leaves them unexplored, and relies structurally on an uninspired starting point (i.e. confessing to a therapist) and gimmicks.

![]() David Cote, Observer: In its slow-burning and fitfully engaging middle, Job ramps up from Boomer-versus-Millennial jousting to a rather contrived Big Twist, left unresolved by an ambivalent shrug of an ending. The rickety whole rests on a couple of prolonged teases. First: is Jane reliable or crazy? Can we trust anything she says; do periodic bursts of noise and light (designed by Cody Spencer and Mextly Couzin) suggest a mind fracturing under trauma? The second big mystery: does Loyd lead a horrific double life? Neither scenario is adequately deepened or resolved. She might be nuts; he might be a criminal. Unlike superior two-handers—like Oleanna or Blackbird—in which men and women square off over meaty dramatic issues, Friedlich coasts on withholding information and padding out back story (Jane’s sad childhood, sadder romantic life). As with many writers who grew up in the golden age of TV, his dialogue is slick, the humor glibly dark. Still, a content moderator deranged by work has been explored more deftly elsewhere, such as Anna Moench’s 2021 Sin Eaters, livestreamed by Theatre Exile during the pandemic.

David Cote, Observer: In its slow-burning and fitfully engaging middle, Job ramps up from Boomer-versus-Millennial jousting to a rather contrived Big Twist, left unresolved by an ambivalent shrug of an ending. The rickety whole rests on a couple of prolonged teases. First: is Jane reliable or crazy? Can we trust anything she says; do periodic bursts of noise and light (designed by Cody Spencer and Mextly Couzin) suggest a mind fracturing under trauma? The second big mystery: does Loyd lead a horrific double life? Neither scenario is adequately deepened or resolved. She might be nuts; he might be a criminal. Unlike superior two-handers—like Oleanna or Blackbird—in which men and women square off over meaty dramatic issues, Friedlich coasts on withholding information and padding out back story (Jane’s sad childhood, sadder romantic life). As with many writers who grew up in the golden age of TV, his dialogue is slick, the humor glibly dark. Still, a content moderator deranged by work has been explored more deftly elsewhere, such as Anna Moench’s 2021 Sin Eaters, livestreamed by Theatre Exile during the pandemic.

![]() Robert Hofler, The Wrap: When Jane isn’t talking about kiddie sex and people’s weird eating habits, your mind might wander. Why does Loyd not grab Jane’s knapsack, where she keeps the gun, since he has multiple chances in the course of the play to do so? You also have to wonder why any tech company would ever considering rehiring Jane after she has subjected her coworkers to a screaming fit atop a desk. And above all, why would Jane think that pulling a gun on a therapist by way of introduction would be a good way to achieve her ultimate aim. That goal is the play’s big ah-ha moment, and as plot twists goes, it crumbles at a moment’s reflection.

Robert Hofler, The Wrap: When Jane isn’t talking about kiddie sex and people’s weird eating habits, your mind might wander. Why does Loyd not grab Jane’s knapsack, where she keeps the gun, since he has multiple chances in the course of the play to do so? You also have to wonder why any tech company would ever considering rehiring Jane after she has subjected her coworkers to a screaming fit atop a desk. And above all, why would Jane think that pulling a gun on a therapist by way of introduction would be a good way to achieve her ultimate aim. That goal is the play’s big ah-ha moment, and as plot twists goes, it crumbles at a moment’s reflection.

![]() Nolan Boggess, Theatrely: Whether or not the audience will be up to the challenge is a larger question. While the tension remains when the gun goes away, the show slowly oozes out information like an IV drip. At times, the show’s desire to remain obtuse gets in its own way. But, unlike its other less-successful, black-mirroresque peers, I promise Job’s final rattling, supreme reveal is worth it.

Nolan Boggess, Theatrely: Whether or not the audience will be up to the challenge is a larger question. While the tension remains when the gun goes away, the show slowly oozes out information like an IV drip. At times, the show’s desire to remain obtuse gets in its own way. But, unlike its other less-successful, black-mirroresque peers, I promise Job’s final rattling, supreme reveal is worth it.

![]() Dan Rubins, Slant: The play’s climactic pivot from thoughtful interrogation toward shock value finally positions it neither as psychological thriller nor dark comedy, but as horror. In describing, if never depicting, the truly grotesque and evil, Job achieves a sort of tonal homecoming. But its horrors are very real, involving the darkest corners of human behavior. They’re also inexcusably unexplored. Lobbing the bleakest imaginable themes at the audience simply to make the play’s lurid twists pay off makes this hollow play less of a job well done than a piece of work.

Dan Rubins, Slant: The play’s climactic pivot from thoughtful interrogation toward shock value finally positions it neither as psychological thriller nor dark comedy, but as horror. In describing, if never depicting, the truly grotesque and evil, Job achieves a sort of tonal homecoming. But its horrors are very real, involving the darkest corners of human behavior. They’re also inexcusably unexplored. Lobbing the bleakest imaginable themes at the audience simply to make the play’s lurid twists pay off makes this hollow play less of a job well done than a piece of work.

![]() Jonathan Mandell, New York Theater: This twist apparently disturbs me more than other theatergoers, even those who agree it is misguided. But to me it fits into a pattern I’ve noticed among emerging playwrights that arguably reflects the pernicious influence of film and TV. The play is full of tension, and twists, in a way that reminded me of several plays over the past few years – such as Small Engine Repair by John Pollano, Office Hour by Julia Cho, Blackbird by David Harrower – that offered shock for shock’s sake. Ironically, the effect of “Job” on the audience feels analogous to something that Loyd warns happens to people who spend too much time with their smart phones — the “slow drip of dopamine” that stimulates them with sensation but stops them from thinking.

Jonathan Mandell, New York Theater: This twist apparently disturbs me more than other theatergoers, even those who agree it is misguided. But to me it fits into a pattern I’ve noticed among emerging playwrights that arguably reflects the pernicious influence of film and TV. The play is full of tension, and twists, in a way that reminded me of several plays over the past few years – such as Small Engine Repair by John Pollano, Office Hour by Julia Cho, Blackbird by David Harrower – that offered shock for shock’s sake. Ironically, the effect of “Job” on the audience feels analogous to something that Loyd warns happens to people who spend too much time with their smart phones — the “slow drip of dopamine” that stimulates them with sensation but stops them from thinking.

![]() Gillian Russo, New York Theatre Guide: Though superbly acted and unrelentingly tense under Michael Herwitz's direction, that conversation reveals little food for long-term thought beneath its slick veneer. The most interesting theme — one of many that, for better or for worse, make Job feel less like a period piece and right at home in 2024 — revolves around responsibility and action: Jane believes her job as an online content moderator, viewing and destroying disturbing media, is as essential as that of a frontline worker, which she relishes. It forces her to actually sit with the world's evils and do something more meaningful about them than shouting into the void of Twitter (I'm not calling it X) and the like. It gives her power, she says.

Gillian Russo, New York Theatre Guide: Though superbly acted and unrelentingly tense under Michael Herwitz's direction, that conversation reveals little food for long-term thought beneath its slick veneer. The most interesting theme — one of many that, for better or for worse, make Job feel less like a period piece and right at home in 2024 — revolves around responsibility and action: Jane believes her job as an online content moderator, viewing and destroying disturbing media, is as essential as that of a frontline worker, which she relishes. It forces her to actually sit with the world's evils and do something more meaningful about them than shouting into the void of Twitter (I'm not calling it X) and the like. It gives her power, she says.

Average Rating: 58.3%

- To read more reviews, click here!

- Discuss the show on the BroadwayWorld Forum

Reader Reviews

Powered by

|

Videos