Interview: Pulitzer Prize-Winning Martyna Majok On Why Stories Like COST OF LIVING Belong on Broadway

Majok was awarded the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for Cost of Living.

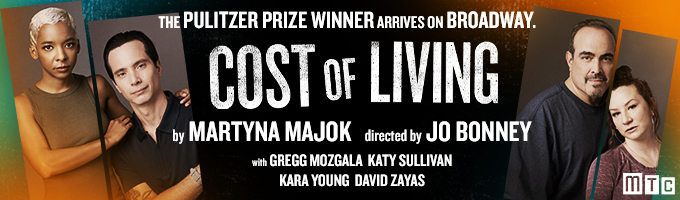

Playwright Martyna Majok was awarded the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for her her play Cost of Living, which debuted on Broadway this fall. This award-winning play about caring and being cared for, and the ways in which we need one another, featured Katy Sullivan (Ani), Gregg Mozgala (John), Kara Young (Jess) and David Zayas (Eddie).

Majok's other plays include Sanctuary City, Queens, and Ironbound, and her incredible list of awards include The Hull-Warriner Award, The Academy of Arts and Letters' Benjamin Hadley Danks Award for Exceptional Playwriting, Off Broadway Alliance Best New Play Award, The Lucille Lortel Award for Outstanding New Play, The Hermitage Greenfield Prize, as the first female recipient in drama, The Champions of Change Award from the NYC Mayor's Office, The Francesca Primus Prize, two Jane Chambers Playwriting Awards, The Lanford Wilson Prize, The Lilly Award's Stacey Mindich Prize, Helen Merrill Emerging Playwright Award, Charles MacArthur Award for Outstanding Original New Play from The Helen Hayes Awards, Jean Kennedy Smith Playwriting Award, ANPF Women's Invitational Prize, David Calicchio Prize, Global Age Project Prize, NYTW 2050 Fellowship, NNPN Smith Prize for Political Playwriting, and Merage Foundation Fellowship for The American Dream.

BroadwayWorld spoke with the Pulitzer Prize winner about the inspiration for her work, writing stories about underrepresented communities, her journey as a playwright, and more.

Your play Cost of Living won the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. What did it feel like to win the Pulitzer Prize for that work?

.jpg?format=auto&width=1400) Incredible, to say the least! It was a total surprise, so much so that when they announced it, my agent called me immediately, and we were on the phone for about 10 minutes because I didn't believe him. He called me and said, "Martyna, you won the Pulitzer," and I was so mad at him because I thought he was messing with me. So, immortalized on my phone, it was nine minutes and 48 seconds that I was just yelling at him, so upset. And then he was like, "Why don't you just hang up the phone and give it five minutes," because the announcement was livestreamed, so I was just Googling my name, and I couldn't find any writing about it. So, I was like, 'Fine, I'll hang up the phone, and I'll give it some time.' And then I saw that I had about 20 texts, and the first one said, "Congratulations!" and I was like, "Oh, it's true!" And then I called back and apologized to my agent [laughs].

Incredible, to say the least! It was a total surprise, so much so that when they announced it, my agent called me immediately, and we were on the phone for about 10 minutes because I didn't believe him. He called me and said, "Martyna, you won the Pulitzer," and I was so mad at him because I thought he was messing with me. So, immortalized on my phone, it was nine minutes and 48 seconds that I was just yelling at him, so upset. And then he was like, "Why don't you just hang up the phone and give it five minutes," because the announcement was livestreamed, so I was just Googling my name, and I couldn't find any writing about it. So, I was like, 'Fine, I'll hang up the phone, and I'll give it some time.' And then I saw that I had about 20 texts, and the first one said, "Congratulations!" and I was like, "Oh, it's true!" And then I called back and apologized to my agent [laughs].

The award is incredible, I'm incredibly grateful, and so honored, and it was an absolute surprise. And it's especially meaningful because it amplifies and lifts up stories like this. I think I was afraid that it was going to be seen as this small story of four people, these two couples, when I've always imagined it to be in conversation with something larger, something cosmic, something sociopolitical. And to have it be recognized in that way is incredibly meaningful for the play, and I hope for stories that are like it.

Your work often features the stories of underrepresented communities. What inspires you to write the plays that you write?

I feel like the term 'underrepresented communities' mostly came from the outside, in regards to the characters that I was writing. In regards to writing, it was stories of my friends and family, and stories of myself, and then when I shared them with a larger group of people, they were labeled 'underrepresented and marginalized communities'. But the beginning of it wasn't necessarily a political act, writing the personal became a political act because then I realized how few stories that we have that get to a wider audience. And so, now there is a responsibility to feel like I'm not perpetuating dishonesties about any one particular group, including groups that I am a part of, in writing, while also sourcing from people that I know, people that I have been.

Maybe it was unconscious, but when I began writing, I wasn't seeing very many immigrant characters given full life in stories, they'd be this tertiary character that would come sweeping into a narrative as the janitor, or some kind of one-scene type of character, offer some sage advice to the main character, and then sweep out of the narrative. Or they'd be the butt of the joke, and their English would be made fun of. I wanted to see my mother on center stage. I wanted to tell her story with 'Ironbound', and wanted to tell the stories of the people that I grew up with, and that I was. They say, 'Write what you know,' but I feel like I'm writing what I don't know about what I know. There is usually some kind of a quest or question that I have, that I need to commune with for longer in my life in ways that I can't, that I need to make up fake people and craft them into an arc to understand what it is. So, I'm pulling from the people that I know and the communities that I've been a part of to live in those worlds, but then I'm still wondering about some kind of personal question that I'm dealing with in a narrative about them-slash-us.

On that note, what was the inspiration for Cost of Living?

Cost of Living came about incrementally. I began writing it when I'd just moved to New York, and it was a year of incredible financial precarity. I didn't have enough for a security deposit for an apartment, so I ended up sublet-hopping for basically a year. I had 13 apartments in one year, the second of which had bed bugs. I got fully hazed by New York City [laughs]. When I moved in they like, "How dare you try to pursue your dreams," and they sent the actual locusts at me. It was so difficult. I was trying to get on my feet by working a bunch of bar jobs and restaurant jobs, while also trying to write plays. One day in January I got fired from a bartending job because the boss thought that I stole 100 dollars, which I didn't, but I wish I did anyway because I got fired for it. It was a Saturday night, I went home to my sublet in Brooklyn, and it had just started snowing, and it was the first time in a while that year since I moved to New York that things were quiet. Because there was no place I had to be, I didn't have to be working, I wasn't expected anywhere, I couldn't pursue my survival that night because my survival got taken away from me.

So, I came home in this blizzard, and I sat at a coffee table that was not my own in this sublet. And I started thinking about the past year, and the losses that I had been accumulating, financial, and also I had lost relative, the man who was my father figure had passed a bit before then, and I, at the time, didn't have enough money to go to his funeral. He lived in Poland, and he died pretty unexpectedly. I also didn't want to go because I was afraid of it being real. I didn't want to confront the fact that this person was gone, and so, in this soup of emotions that night, dealing with my grief that I hadn't dealt with because I went right into work and survival, as well as the loss of a job and questioning, "What am I going to do?" in the beginning of my career and this life, and "Is this life actually even for me? Can I do this?" I started writing. And the first thing that came was the monologue for Eddie Torres.

I recalled when I was living in Chicago, I used to work as a caregiver to two men with disabilities. And so, I pulled from that experience to write the shorter version of the John and Jess story. At a certain point in that year, I wrote the first scene between Eddie and Ani. I didn't realize it was them, but when I wrote their scene and listened to it, I realized the man sounded very similar to the man that I had written the monologue for, and I realized, "Oh, this must be his wife," and, "Oh, I guess she's dead, let's find out how that happens." These four characters started to feel like they were speaking to each other, all of them dealing with aspects of care and need, and a kind of yearning and loneliness. And so, the task of that year then became, "What are they saying to each other? Why do they exist in the same world? What do they have to teach me?" I just tried to write to answer that question for myself.

.jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

Cost of Living opened on Broadway this past October. What was the most memorable or meaningful part for you about Cost of Living's debut on Broadway?

Beyond the larger meaning of having a play amplified on Broadway, especially a story like that, I was so happy to be able to share it with more people. It especially was impactful for me, and it seemed like for audiences. I was writing in a place, many years before where there were many breaks in my life, there were so many losses. And after our years of the pandemic, I felt like we collectively experienced a lot of different losses, many forms of grief, and there was something that felt very different in the theatre when we did it on Broadway than when we did it in 2017. It couldn't have come at a better time.

I deeply needed it to be this fellow traveler with my current grief, to be a companion for me. When we did the first reading on our first day of rehearsal, there was something palpable in the air of us all gathering to share in this story of people needing each other and communing with their losses. It was really important for me personally, and it did seem like there was something that people were connecting to, especially after the last few years that we had. Stories like this belong on Broadway. Whether it's mine, or someone else's, stories like this about these worlds absolutely belong on Broadway. And so, I hope that it continues, and I'm so happy and grateful to have been a part of the great history of Broadway.

Can you tell me a little bit about your writing process?

I always reference this quote, Leonard Cohen said, "If I knew where the good songs came from, I'd go there more often," and every single time I've tried to replicate the writing process of a play, the art just laughs at me, like, "How dare I, in my hubris, think that it's this easy to just do what you did last time." I feel like I'm learning to write every time, with every new play. But I have found that there are two processes. One is very, very fast, Ironbound I wrote in five days, and Sanctuary City I wrote in three days, where I have a clarity of purpose, and character, and what I'm trying to say globally with this constellation of characters in conversation with each other. And those, I won't leave my apartment, it will be a fever pitch of writing. It usually helps if I have a very specific structure in mind.

And then there are the other plays like Queens, and Cost of Living, which are this accumulation of I'll hear a character, I'll see it, and then I'll put it on the page and keep investigating what these people are trying to say to each other, and then also to me, trying to surprise myself in seeing where they might go based on the ending of one scene. And I never know how long they're going to take. Those plays, I call them the back-of-the-brain play, and the other ones are the front-of-the-brain-play. It just feels like a dotted line that goes straight to the page with a front-of-the-brain play, whereas the back-of-the-brain play, you're reaching for something you can't see constantly. And that process tends to be writing until it feels honest.

That was a lot of the experience of Cost of Living. For a while I had the whole play except for the ending and the title. And I was like, "Well, I know how plays work, at some point these two parallel stories are going to intersect in a meaningful way," [laughs]. And I just kept on trying to see how they might intersect, introducing new characters, wondering what pairing would end this story in a way that felt satisfying. And I ended up making that choice based on who at the end of the play needed it the most. And so, I ended with Eddie and Jess at the end of the play. And then the play basically told me what it was about when I found that last scene.

Cost of Living made history with Katy Sullivan being the first woman amputee to star in a Broadway show. How do you hope that Cost of Living will help influence changes in the entertainment industry in terms of representation and disability inclusion?

.jpg?format=auto&width=1400) When I wrote, "Please cast disabled actors" in the notes, I didn't realize what a big political act that was going to be. I had written it because I thought, "Maybe just in case people have any questions about whether they should do this or not, let me just have a safeguard." There had been the incident with Katori Hall's The Mountaintop not too long from when I had written that note, where somewhere in America they cast a white man to play Martin Luther King Jr. She was like, "Why are you doing that?" and the rationale was, "You didn't specify in the play that it had to be played by a black actor." I think hearing that I thought, "Well, let me, just in case, write it in."

When I wrote, "Please cast disabled actors" in the notes, I didn't realize what a big political act that was going to be. I had written it because I thought, "Maybe just in case people have any questions about whether they should do this or not, let me just have a safeguard." There had been the incident with Katori Hall's The Mountaintop not too long from when I had written that note, where somewhere in America they cast a white man to play Martin Luther King Jr. She was like, "Why are you doing that?" and the rationale was, "You didn't specify in the play that it had to be played by a black actor." I think hearing that I thought, "Well, let me, just in case, write it in."

And since then, I had gotten a lot of theaters asking me whether I really mean it. They would call my agency and basically ask my permission to not cast disabled actors. And when they would do that, then I would furnish them with a list of, "Here are some understudies we've had on the show," or "Here are people who came in to audition," "Here are these theater groups like TBT and Deaf West that have groups of disabled actors and other artists that you can approach, or maybe you can make a casting call in your community," etc. and then I wouldn't get a response back from them. So, it seemed like they didn't actually have an investment in doing the play or having change happen, they just kind of wanted permission to keep on doing what they'd always been doing. I feel like I probably have lost income by holding firm on that. But it doesn't make sense to me, there are so many incredible actors. And so, I feel like if this is one of many opportunities that actors have to showcase their talent in ways that they haven't been able to do, then I'll keep on holding firm on, "Please cast disabled actors."

I never intended to write a play about disability. It was about all the other things that it's about. It's about loneliness, and about class, and these socio-economic concerns, it's not about disability any more than it's about immigration, or about women, because there are two of those in the narrative [laughs]. But I've always tried to write character first, and that happened to be whatever identity that they are, while trying to be responsible about how they were going to portrayed, particularly when there has been such dishonesty perpetuated, or limitations perpetuated on many identities that were quote-unquote 'underrepresented'. It also didn't seem like a political act, again, I was writing about my friends and family. And then writing, "Please cast disabled actors," then became this political act that I felt like I could stand behind.

Cost of Living began performances on Broadway in September 2022 and ran through early November 2022. It is currently nominated for four Drama League Awards, and an Outer Critics Circle Award.

Videos