Interview: Elaine Romero Talks Culture, Border History, Human Rights, and World Premiere of EL TIRADITO

Romero's new play is funded by Confluencenter for Creative Inquiry at the University of Arizona through a grant from the Mellon Foundation.

A longtime Tucson resident, Elaine Romero enjoys national acclaim as a playwright, though her local impact remains relatively unrecognized. Akin to the proverbial prophet in her unwitting town, the prolific dramatist has penned nearly 110 plays and is rightfully due for local recognition with her latest project: EL TIRADITO.

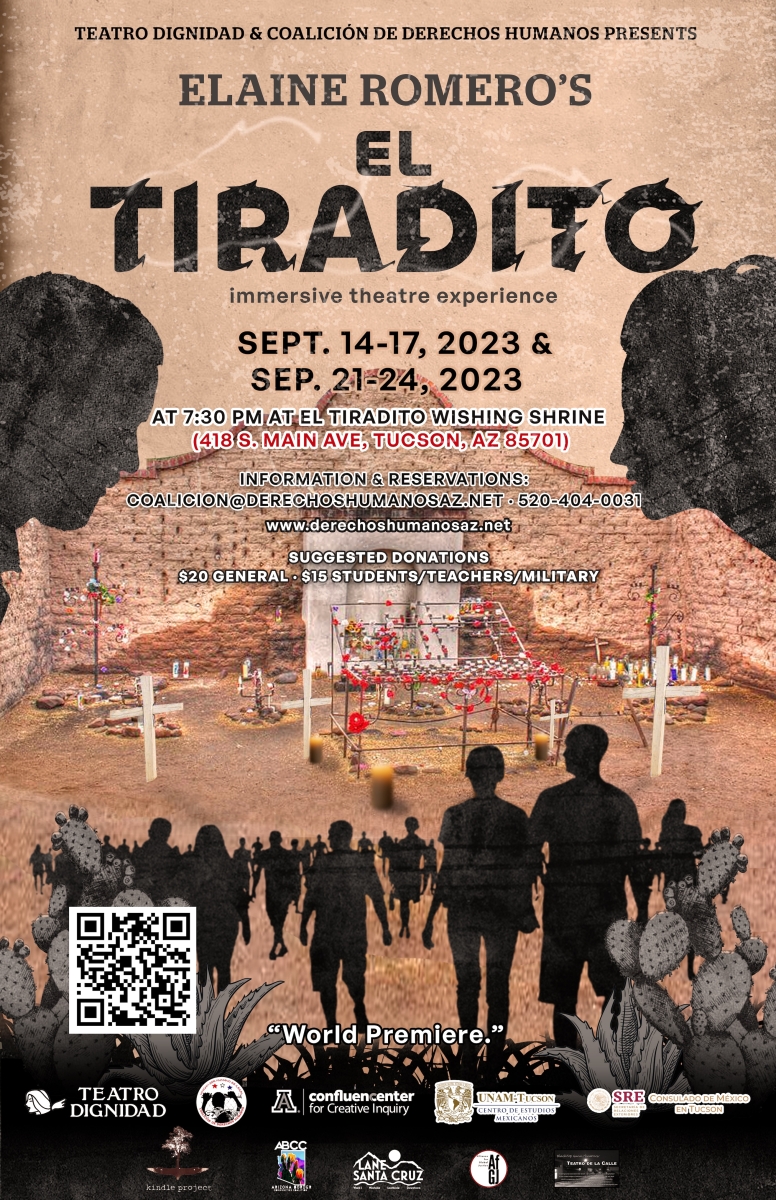

The play is an immersive celebration of a Tucson historical landmark: El Tiradito, also known as "The Wishing Shrine." Originally associated with a legendary love triangle that met a tragic end, El Tiradito has evolved into a sacred site for both the faithful and the heartbroken and a cherished spot for poets, writers, and artists.

This weekend, Tucsonans have the privilege of witnessing the site through the lens of a master storyteller. The interview uncovers the inspiration, challenges, and profound insights that shaped Elaine's remarkable play. Renowned for her impressive repertoire that captures the emotional essence of culture and history, Elaine charts the play's development while keeping the pulse on the spiritual underpinning of her work.

I've been meaning to do a profile on you and the fantastic work you do nationally. But there's something immediate for us to discuss: a world premiere of a new play based on a legendary local site. Tell me how EL TIRADITO got started.

I'm going to tell you specifically because Alba Jaramillo, our producer, has this theater called Teatro Dignidad, which is a local theater, but a company within the umbrella of Coalicion de Derechos Humanos that's focused on producing plays that address issues of human rights. We have funding through the Confluencenter for Creative Inquiry from the University of Arizona, and they had Mellon Foundation money. What's amazing is she wanted to work together, and she wanted to find a way to both honor the activism of the site of El Tiradito and the years of activism that have happened there but to do it in a creative way. So she came to me and asked me at the beginning of the year if she could commission me.

That's quite a turnaround.

And it was crazy because I thought, that's soon! She wanted to do the first 20 pages in the art gallery, RAICES TALLER, which we did back in May. And then, before the play was written, she wanted a sample to get the audience excited. So we did that, and I started working with actors and thinking about how I would write the play. And it was at that time that I realized the play could have three storylines. The historical, mythological storyline of what actually happened and how it was founded; the storyline of an activist and someone moving toward becoming an activist; and the storyline of a person who has crossed in the past.

This kind of work is right up your alley.

I'm very interested in how time collapses and how history is layered on top of history. And time is layered on top of time, and character is layered on top of character. And this is what draws me -- to be able to find that way to layer everything. So everything's happening in the past, the present, the future, and all at once. And that's what excites me.

How big is the cast?

Seven actors. It's an ensemble piece written for these actors. And what's beautiful is you look up at this cast, and it's a bunch of Latine actors who live here, and it's about our story, about us. And man, I love it.

Is Alida Gunn directing it?

Alida is directing it, and she's a hell of a good director. Very, very specific. And you know, she has a connection to the place as well. I mean, we both have a connection to El Tiradito itself. I used to live down the street and walk there all the time every day.

Assuming that only some people know about the place, what would you say El Tiradito is about?

That's a really good question. I always assume I know it, but I find myself introducing people to it regularly. I say it's a shrine to the unconsecrated soul. It's for the imperfect person. It's for the impossible. It's for the things that you don't think can work out. It's for your longings; it's for your heart. You know, the play is very much driven by love. And I heard myself saying in yesterday's rehearsal that everybody should be desperately in love with everybody else.

How do you feel about the play itself? You had to write it fast, so is it done, or is it still in process?

I'm so excited about the script. There are elements of the script that remind me of my favorite plays I've ever written. I didn't realize it the first day. I realized it a few days in when we had the full script and we were starting to hear it. And I heard echoes of me, my writing, and my highest ambitions as a writer. And isn't it interesting that this play – this place, these people, these actors, this director, this producer, have inspired this in me!

And it's just that spark of being here, that sense that all of us who love this place feel, that's so powerful and much louder in us than any conversation about the border and any stupid border wall.

To a playwright, commissioned work must be ideal. But this sounds like more than just another project. It’s meaningful because it's personal.

This is about our highest selves. It's about tapping into what really matters. It's really the earth. It's the fact that I know the border's not real. It's the fact that so many have died trying to get here. And what do they get when they arrive? It's the fact that these vigils have been held for over 23 years in memory of those we've lost on the border, that people have held up the story and said, "Don't forget." And to be part of that is such an honor.

You know, it's interesting with commissions and any play, but particularly with the commission, you must find your passion portal to enter the story. I believe that about all, whether you're the dramaturg of a play or directing it, acting in it, or writing it, you have to find your way in. And this story did invite me in. Once I knew it was going to be complex, it would have these three storylines. I know other plays of mine with multiple storylines and the demands of writing a play like that.

A passion portal. I appreciate that sentiment.

If you're an actor who takes on a role, you have to find your way to love that person. No matter who they are and what they've done. That's how I feel; I love all these characters.

And how much of them are based on real people versus symbolic characters?

We use the actual names of the dead in the play. The characters of the activists and the journalist are all created -- you know, through many years of experience on every side of the desk, but also years of experience interacting with people from activism and interviewing different people. And Alba Jamarillo (I won't say anything is based on her because it isn't) -- the fact that she really is the person I was able to get a lot of actual information from, that I knew the theater would want represented in the play without making it a problem. So, the play truly represents the story. We've held ourselves so that an activist comes and feels like their story is there, without making it so nobody else feels welcome. There is a balance of that kind of storytelling. And I'm enjoying doing it. I mean, I've loved this process.

The play is focused locally, but is there an opportunity to take the story beyond Tucson?

Oh, there is. And I plan to. I talked to Alba; her organization is in DC. I said we need to bring this story to DC. My plays are not all political, but many of them are. I have a series of war plays, and I have a series of border plays. You recall because you were part of TITLE IX [as an actor]. That was one of the border plays. So, these plays belong in DC, where decisions are being made. They belong at theaters all over. The fact that we're doing it outside is great, but it's written in such a way that it could be done with a set that represents El Tiradito. It has that kind of theatricality that will exist now and later in other places and invite other communities to participate in us.

And that's the magic of something local that resonates everywhere.

Just think about all the conversations about the border, all the people, no matter what side of the aisle they're on—the "being tough" narrative. And you know, you and I know the history of this place. We know the history of Mexico here. We know the story; we know what happened in these lands. Nobody's going to retool our brains to think that, "Oh yeah, this was always the United States." We know it wasn't. And that history, the pain of that history, and the brutality of our history have created this tenseness, this intensity.

The fact that somebody can go to Washington and talk about our border -- good luck with that. Good luck with understanding who we are in this place. It is incumbent upon us to talk about what it is TO BE US here in the story. Somebody arrives here, somebody's already here. All those different stories exist within this play. There are so many disturbing things in the world, but an anti-immigrant sentiment is incredibly disturbing to me. It's antithetical to who we are as a country and who we claim to be. It's antithetical to our Statue of Liberty. It's antithetical to everything we believe about We The People. And if we can't be the inviter of all, if we can't be the balm of the world, we don't know who we are.

So hey, let's do local. Let's do it here; let's do it with my friends of many years. What a treat to work with people I love and admire. You know, at the heart of everything we do is respect for each other and each other's work. I came through a certain kind of training in theater, and a certain kind of doing theater, and everybody's coming from a different place, but we're all meeting together to tell this story. I love that we could just all be here and do the work. I love collaboration!

Your passion for this particular project is palpable. I appreciate the clarity of your mission.

As you know, my ancestral history is New Mexico, and we're so far back that the border crossed us. That is in many of my plays. It's my family history. And it is interesting to be of a place and then to be treated as the "other" of a place. And that's what happened. The people left behind, who became Americans by default, lost their land, language, and culture to this Manifest Destiny deal. And having that in my DNA and history, I feel like I am the earth they walked upon to get their manifest destiny. I'm the body underneath that. And my ancestors are the bodies underneath that.

And it's interesting how I was given this English. I got this English because people planned that. My grandparents fought for it. My mother fought for it. She read to me famous poets when I was a little child -- "Tyger, Tyger, burning bright, in the forests of the night." She would read us this stuff so we could get the rhyme and meter of English. And when I hear my work in Spanish, I always feel like, oh, that's the language it's supposed to be in. Right. And my mother says to me, "Elaine, you have a Spanish mind," because she looks at what I write about. She looks at the geography of thought. She looks at the cosmology of Elaine, the lexicon of Elaine. And if you look at the multi-worlds that I deal with and the sense of the dead and the living being connected, it's all rooted in culture more than any literary tradition.

It's not that I don't know Spanish, but it's fascinating, even in my own family, how are we going to meet the moment of being Americans? And it's decided it was gonna be through language. My mother ended up going to college when she was 16. My grandfather was so worried she wouldn't get an education they sent her off when she was 16. But I love language, and I love getting a line right. And hearing it in the actor's mouth and then changing something or hearing something in Spanish in my mind, putting that in, and just working on it in the process. I've done a lot of cutting of sections of the play as I've heard it. I've done a lot of reorganizing of where the text goes and where the story goes. I've done a lot of dealing with non-chronological storytelling.

As a writer, placement is everything. This process has given me all of that. And I can't wait to have people there. I can't wait for that place to be even more revivified by the energy of our community, my play in the story, and our community showing up to that place.

You've been at the University for a while now. What is your official title?

Associate Professor in the School of Theater, Film and Television. And we say of playwriting and dramaturgy.

And you are still involved with Arizona Theatre Company?

I'm the playwright in residence there, and I've been advocating and continue to advocate for Latine artists. Yeah. We run a really robust contest. And those plays have been produced all over the country and with us. And that theatrical home is just steps away from El Tiradito.

Many years ago, I had the good fortune of acting in several of your plays. They were some of my best memories on the stage. Now and then, I fantasize about doing another play of yours.

Oh, thank you. You know, we can make that dream come true. I'm serious. I feel so blessed to be in this community. And even though I was not always able to have my work produced here, I was always fed by the beauty of your performances.

Well, I thank you back. I wish you well in what looks to be a promising endeavor. We hope to get more local audiences to appreciate your work the way they do outside the old pueblo. You're one of those unacclaimed prophets in their own town.

David Goldstein used to tell me the same thing: A prophet is not welcome in their own town. And I always thought, well, if we're going to have a hometown...

Then let it be the world, right?

[But] you have to be where the earth feeds you. I'm inspired to write here every day. I live in a historical home. There is something about it that's healing. Even my house itself remembers everything.

Headshot Credit: Carolyn Rae Maier

For tickets, visit:

Comments

Videos