Exclusive: Hasna Muhammad on Shadowing the Call at PURLIE VICTORIOUS

Purlie Victorious played its final performance on February 4, 2024.

Purlie Victorious may have played its final Broadway performance months ago, but the acclaimed production was not forgotten by Tony nominators. The revival earned six 2024 Tony nominations, including Best Revival of a Play. BroadwayWorld is very excited to share an exclusive essay written by Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee's daughter, Hasna Muhammad, who played a key role in getting this landmark play back on Broadway.

Enjoy "Shadowing the Call" by Hasna Muhammad below:

I reported to the stage door of the Music Box Theatre and waited for the Stage Manager to greet me. After a few minutes, Giselle Raphaela appeared, and I followed her across the stage, past an off-stage alcove and the quick-change space to where Kamra Jacobs, the Production Stage Manager, greeted me too. I had come to shadow the call of the 131st performance of the 2023 revival of, Purlie Victorious, which was written by Ossie Davis (my father), directed by Kenny Leon, and starred Leslie Odom, Jr. and Kara Young. I had seen the play from the house many times, but that night would be the first time I would watch the performance from backstage.

My father and Ruby Dee (my mother) starred in the original 1961 Broadway production of Purlie Victorious at a time when there were fewer Black stories, playwrights, and actors on Broadway than there are now. Their activism included fierce advocacy for diversifying the “Great White Way” not only on its stages, but also behind the scenes. They used to talk to me about the need for more Black crew members, hair stylists, and makeup artists. More Black directors, producers, stage managers, and even theatre owners on Broadway. Having Kamra and Giselle—not one, but two BIPOC women—manage the Broadway stage of Purlie Victorious was the plan made manifest. Kamra and Giselle were the folks my parents were fighting for.

And that’s what I told them one evening when we met at a nearby restaurant to talk about the women of Purlie Victorious—not only the female actors and characters, but also the many women who worked on the production. With Kamra, that meant talking about the orchestration of bringing Kenny Leon’s vision to fruition. With Giselle, it meant talking about the logistics of everything and everybody onstage and backstage before, during, and after the show. With both, it meant talking about their passion for the artistry of stage management.

Kamra has been a stage manager for 10 years and has worked on such shows as Top Dog Underdog and Fat Ham while Giselle’s first job as a stage manager was Purlie Victorious. After subbing-in and “learning the track,” Giselle took over for Benjamin E.C. Pfister the last few weeks of the run. Kamra and Giselle took turns calling the show and managing the stage in an environment where shadowing, interning, and mentoring are the fabric of learning the job and doing it well.

Kamra has been a stage manager for 10 years and has worked on such shows as Top Dog Underdog and Fat Ham while Giselle’s first job as a stage manager was Purlie Victorious. After subbing-in and “learning the track,” Giselle took over for Benjamin E.C. Pfister the last few weeks of the run. Kamra and Giselle took turns calling the show and managing the stage in an environment where shadowing, interning, and mentoring are the fabric of learning the job and doing it well.

Kamra went to grad school to build a network of stage managers, and just one class helped Giselle discover the world of stage management. They both started out with an interest in acting but found a different way to be on stage. Being production assistants and working their way up to stage management was where they landed. Stage management gave them a way to be a part of the creative team and to be in the room from day one.

There aren’t many people who look like Kamra and Giselle managing Broadway stages. Kamra often hears from veteran Black actors that they’ve never had a black stage manager before, and she knows that being their “first” represents something important. When I asked Kamra and Giselle if they experience prejudice or marginalization because of their gender or ethnicity, Kamra said that it’s always interesting when she first gets into a theater because people don’t expect to see a black female stage manager. And when they see her, especially people who've been working in this industry for a long time, some don't think she knows what she’s doing. “I just have to lead,” she says. “Command the space because once you get into tech, that theater is now your theater, and the crew is now your crew.”

Alternatively, Giselle may have been hired for one production because of her Latinx background. She thought it was an advantage, but her presence may have been based on a diversity quota rather than her specific set of skills. “It felt a little tricky because I appreciated the opportunity, but it just didn't feel genuine.” Unfortunately, BIPOC women make up a small percentage of non-performance theatre roles. But the faces of stage management students are becoming more diverse, Kamra and Giselle tell me, and those faces will change the look of backstage Broadway.

I ask them both what can be done to increase the number of female BIPOC stage managers, and they say it starts with education. Other than theatregoers who read the Playbill, most people only know the story they’ve come to hear or the actors they’ve come to see. Some may know the playwright or the director, but most don’t know who the stage managers are and what stage managers do in the production, let alone how to become one. "This is a career. This is a sustainable, fun job,” they both tell me at different times in our conversation. Giselle says that it also starts with encouraging more young people to endure the difficulties of a career in the arts as well as encouraging them to go to the theatre.

Kamra never got to see what the inside of a Broadway theater looked like until she was working on Broadway. She never thought she would be on Broadway. “I met Kenny in 2017. I didn't expect to be working with him on Broadway six years later. You have these ideas that it's bigger and it's so unattainable because it's Broadway.” Giselle didn’t grow up going to the theatre either, and she was uncertain about how long it was going to take her to break into the industry because she didn’t see people her age or those who looked like her. If it weren’t for the encouragement of colleagues, she might have given up. Both Kamra and Giselle recommend starting out as a production assistant and say that if you're good at your job, you won't be a PA for very long. People will get to know your work and will want you on their team. “It's important to not let people determine what your dreams are,” Kamra insists.

Kamra never got to see what the inside of a Broadway theater looked like until she was working on Broadway. She never thought she would be on Broadway. “I met Kenny in 2017. I didn't expect to be working with him on Broadway six years later. You have these ideas that it's bigger and it's so unattainable because it's Broadway.” Giselle didn’t grow up going to the theatre either, and she was uncertain about how long it was going to take her to break into the industry because she didn’t see people her age or those who looked like her. If it weren’t for the encouragement of colleagues, she might have given up. Both Kamra and Giselle recommend starting out as a production assistant and say that if you're good at your job, you won't be a PA for very long. People will get to know your work and will want you on their team. “It's important to not let people determine what your dreams are,” Kamra insists.

Kamra and Giselle emphasized the importance of reaching out, reaching back, and mentorship for BIPOC women especially. Kamra’s career started when she reached out to Narda E. Alcorn (professor, chair, and stage management advisor at the David Geffen School of Drama at Yale) and invited her for coffee just to learn more about her. “Seeing Narda doing this at this level made me realize that this is possible." Now when Kamra speaks to students, she encourages them to reach out to her. She tells students to wait by the stage door for the stage managers the same way that fans wait for the actors. Kamra talked about Black Theater United (BTU) and its Charlie Blackwell Scholarships for Stage Managers of Color. Giselle talked about Cody Renard Richard, the stage manager, educator, and producer who, in partnership with Broadway Advocacy Coalition, created a scholarship designed for “uplifting and supporting the next generation of theatrical leadership of color.” I found that Broadway & Beyond Access for Stage Managers of Color has a scholarship and training opportunities that “aim to eliminate the phrase ‘I don’t know where to find them’ from the hiring process.”

Kamra is currently the stage manager for Hadestown on Broadway, and Giselle just finished as the stage manager for Gun & Powder at the Paper Mill Playhouse. There are other BIPOC women managing on- and off-Broadway, regional, community, and summer stock stages, and there are other people and diversity initiatives multiplying this theatrical force. More importantly, since there is a perpetual loop of preparing the next generation of talented, skilled, organized creatives for the role, there will be many more BIPOC stage managers to come.

As our conversation concluded, I realized that as many times as I had watched the cast and crew prepare before the show; as many times as I had uttered the dialog from an orchestra seat during the show; and as many times as I had participated in talkbacks after the show, I hadn’t experienced the show completely. I hadn’t seen the undergirding of my father’s words. Expecting that I would be a distraction and for her to say no, I asked Kamra anyway if I could watch the show from backstage— “Shadow the call,” she echoed back. And she said yes. A week later, I showed up at the stage door for the 6:00 crew call for the Friday night 7:30 show.

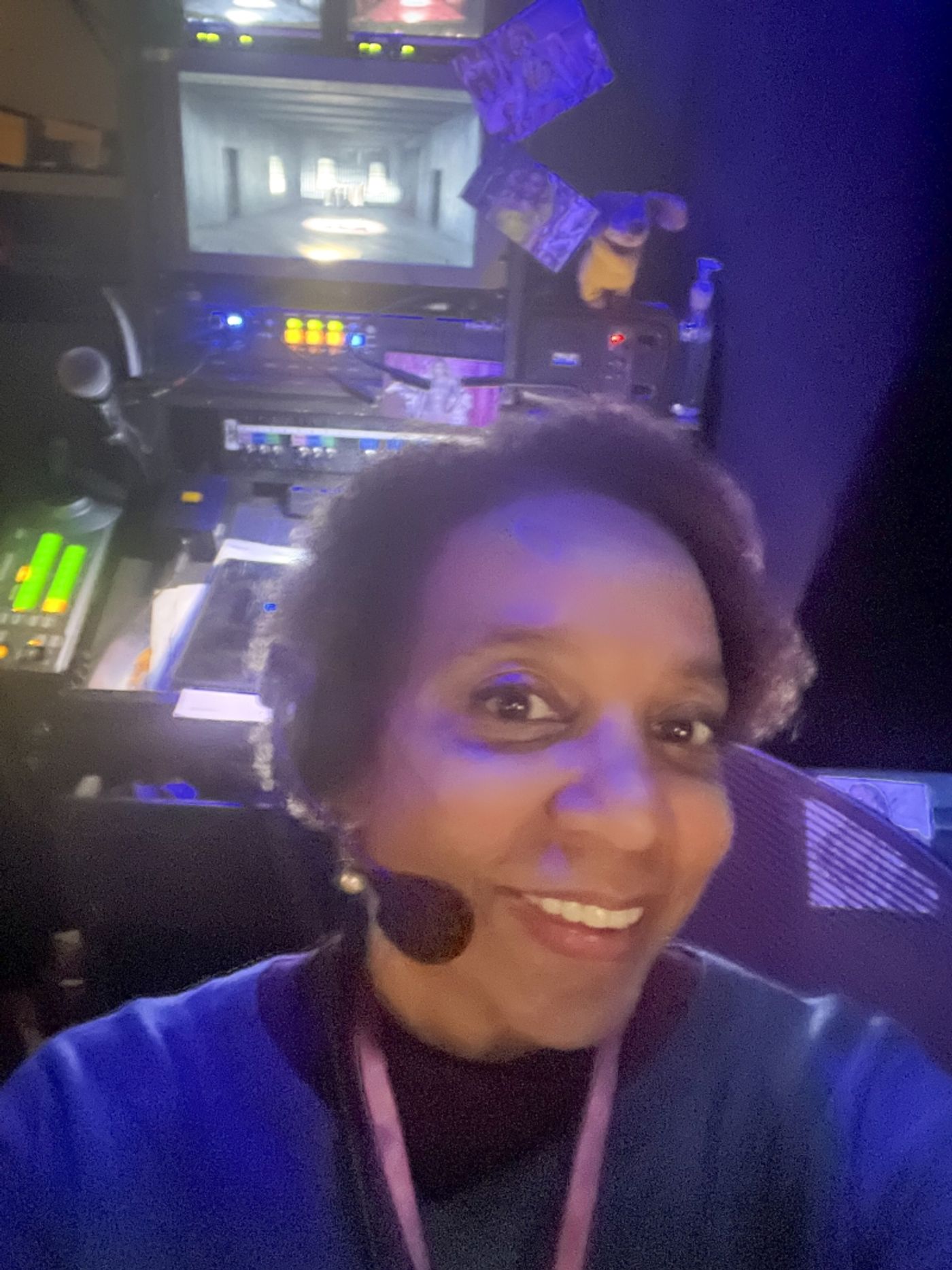

The calling station is a tower of audio-visual monitors nestled in the corner near pipes and electrical panels. There is a speaker on top of three screens that show the stage. One screen shows a static view; the other is infrared which allows people on stage to be seen when the stage is black; and the third is a pan-tilt-zoom (PTZ) camera controlled with a joystick. There is a desk area big enough to hold the control board, the script, and the several hand-held electronic devices for timing the show, communicating with both the front and back of the house, and writing the Performance Report.

As I am given a head set and a company badge, I become the child who’s just been given a pilot wing pin. Then I follow Giselle to the stage through black duvetyn corridors, some lined with pieces of the set or racks of props and supplies. Others serving as interior walls for the backstage spaces. Giselle monitors the tech checks of the moving walls and ceilings for the scene changes, counts and confirms the placement of props, and makes sure the stage is set, safe, and ready for the actors. All the while talking into her headset and checking the list on her clipboard as she goes.

One hour before show time, Kamra opens the stage for vocal warm up before the fight call—the rehearsal of a stage fight. Thirty minutes before the show, Giselle is poised downstage waiting to receive Kamra’s signal that lights and sound are preset and that she can hand over the stage to the house manager. The stage goes black for a few moments, then the lighting for the opening scene shines behind Jonathan Schulman, the House Manager who welcomes everyone to the Music Box Theatre. Before every performance, he greets the ushers with a riddle then declares amid their laughter, “The house is now open. Please enjoy the show.”

One hour before show time, Kamra opens the stage for vocal warm up before the fight call—the rehearsal of a stage fight. Thirty minutes before the show, Giselle is poised downstage waiting to receive Kamra’s signal that lights and sound are preset and that she can hand over the stage to the house manager. The stage goes black for a few moments, then the lighting for the opening scene shines behind Jonathan Schulman, the House Manager who welcomes everyone to the Music Box Theatre. Before every performance, he greets the ushers with a riddle then declares amid their laughter, “The house is now open. Please enjoy the show.”

I sit on a stool behind Kamra who is silhouetted by the lights of her screens. The sound of ushers helping audience members find their seats trickles in through the speakers as Kamra counts down into the backstage com: 15. 10. 5 minutes until curtain. I am still as I listen to Kamra’s voice in my ear giving standby cues and go calls for Kenny Leon’s message that opens the show, the interstitial music written by Guy Davis (my brother), and the entrance of the cast. During the show, Kamra stands in front of her high seat tapping messages into her phone or notes onto her iPad. In sync with the action on stage, she makes crisp turns of the pages of the script that is marked with notes and numbers that signal the calls that trigger what I see and hear as realistic from the house but are really the flip of a switch from backstage. Again, Kamra says yes when I ask if I can cue a light for Heather Alicia Simms (Missy) to enter the stage, and my nerves are abuzz as I do.

A week later, I come back to shadow the call for the 141st performance on a Saturday night. This time Giselle is calling the show, and Kamra is checking the deck. This time, I pay attention to the play behind the play. Crew members carrying props and costumes back and forth. Actors moving their bodies to prepare to go on stage. Shaking their legs. Doing squats. Swiveling their hips. Swinging their arms. Walking back and forth or in circles. Transitioning in and out of character as they move to and from the stage. Off-stage lines are yelled into the walls. Effects make-up is applied and removed, and costumes are changed and adjusted with minor tugs. Sometimes there is running and quick fixes. Some actors have to cross under the stage where they pass racks of clothes, shelves of equipment, and Missy’s left-over sweet potato pie on the breakroom table. All the while, Giselle is focused on conducting the show, and Kamra has her eyes and ears on everything else.

Purlie Victorious closed on Sunday, February 4th, the 19th anniversary of Dad’s death. I sat in the orchestra with my family for the final performance that evening, but I watched the matinee—the 150th show—from the call station. My chest swelled when Giselle said to the cast and crew as well as to me, “This is your places call. Places call. Let’s do what we do. The call is places.” Giselle bounced gently as she narrated her actions to Micah Akilah, another BIPOC stage manager on the other side of us who was also shadowing the call. Kamra mouthed some of the dialog as she watched the stage. I ventured farther from my seat this time and stood against the wall in the wings to watch the actors at work when they crossed into the slice of the stage that I could see. When not on stage, there were hugs and a little bit of pantomimed horsing around. Vanessa Bell Calloway (Idella) took photos with cast mates. Heather danced in silence. I stood still with a heart too full to move.

Purlie Victorious closed on Sunday, February 4th, the 19th anniversary of Dad’s death. I sat in the orchestra with my family for the final performance that evening, but I watched the matinee—the 150th show—from the call station. My chest swelled when Giselle said to the cast and crew as well as to me, “This is your places call. Places call. Let’s do what we do. The call is places.” Giselle bounced gently as she narrated her actions to Micah Akilah, another BIPOC stage manager on the other side of us who was also shadowing the call. Kamra mouthed some of the dialog as she watched the stage. I ventured farther from my seat this time and stood against the wall in the wings to watch the actors at work when they crossed into the slice of the stage that I could see. When not on stage, there were hugs and a little bit of pantomimed horsing around. Vanessa Bell Calloway (Idella) took photos with cast mates. Heather danced in silence. I stood still with a heart too full to move.

I asked Giselle if I could flip the switch for my brother’s music that plays during the transition from Act II to Act III, and she squeezed my shoulder to cue me. At the end of Act III, Giselle leaned in unexpectedly and asked me if I wanted to cue the photo of Dad that faded up on the upstage wall at the end of the curtain call of every show. I slowly inhaled the moment and stared down at my forefinger poised on the switch. For that split second, I was an extension of my father, my brother, and the entire family. I was “in the room” and as close to the production that I would ever be again. Giselle squeezed my shoulder. I pressed down and brought my father back to light for the second-to-last time on this stage.

During our dinner conversation, Kamra and Giselle confessed that they had never encountered Purlie Victorious as a part of the American theatre canon. We listed likely reasons and thought about all the amazing plays that are written that we don’t get a chance to see. Kamra referred to Purlie Victorious as “a special, great American play that is just as important as Shakespeare.” And even though the play was written more than 60 years ago, Giselle was shocked to see how relevant it is today. “It's just the right time,” she said. “It's for me now.” They also told me how much everyone really cared about the show, and that that’s not always the case. I heard that directly from individual crew members and every person at the theatre who I stopped to thank for the work they did; for their part in making Purlie Victorious the success that it was.

The role of a stage manager is exhilarating. There were moments when Kamra watched the stage of Purlie Victorious and thought, "Look what I get to do.” In 1951, my father was the stage manager for the off-off-Broadway production of The World of Sholom Aleichem, a play of Jewish folklore that would later influence his writing of Purlie Victorious—the play as well as the character. My father said that it was when he “looked out on stage from my stage manager’s chair night after night and watched the play about the people from the Polish city of Chelm that the extraordinary power of theatre to educate as well as to entertain was brought home to me.” The first time I sat in a stage manager’s chair, I was overwhelmed into silence. I had no words. Just a mix of emotions that fell as tears as I gasped for air. As I stumbled to describe how I felt after shadowing the call the first time, Kamra reminded me that sometimes just having the experience is enough. So, I just sat there and wept.

Kamra and Giselle warned me that once I shadow the call, I’ll never want to sit in the audience again; I'll always want to sit by the call. I think they may be right.

Videos