BWW Exclusive: Read an Unpublished Chapter About The Beach Boys from Albert Poland's Best-Selling Memoir, STAGES

If you're a regular visitor to BroadwayWorld, you know that we have thoroughly enjoyed and written about Albert Poland's book, STAGES. The book entered the Amazon charts at #1 in its category, as did the recent audiobook debut, again, flying to #1. In the initial article, I stated a quote from Albert's friend, Tania Grossinger, where, during a lunch, she stated, rather simply and abruptly, "Look, I love the book, but you don't have to tell us everything you know."

Well, according to Albert, she was right and he continued to hone the book to what it is today. However, there was stuff on "the cutting room floor" (so to speak) and we were lucky enough to get this chapter from Albert and to share with you. It's quite a read ... and the (never before been seen) photos are pretty damned good, too!

Maharishi And The Beach Boys

(Deleted chapter from STAGES - A Theater Memoir by Albert Poland)

When Rock & Roll burst onto the scene in the mid-50s, Bill Haley and Elvis Presley jolted white America into our sexuality. Like plugging Velveeta into a light socket. After a steady diet of "Abba Dabba Honeymoon" and "How Much is that Doggie in the Window?" this new feeling was so foreign we didn't know what it was. "I feel strange when we're dancing to this," we said as "Rock Around the Clock" played over and over on the little RCA 45.

But late at night, alone in my room I discovered the other music on the Rhythm & Blues radio stations from Memphis and Del Rio, Texas. Here were the raw and real originals: Ruth Brown, Ray Charles, the Penguins, Bo Diddley, Lavern Baker, Little Willie John, Big Mama Thornton, Hank Ballard and Little Richard whose overtly sexual performances were oddly interspersed with advertising for tiny bottles of holy water and other fetishistic religious articles.

It seemed schizoid to hear these sexy, earthy, soul baring performances mixed in with blatant ads for religious items, but I came to realize they were part of the same fabric; two sides of life against death, each offering to save eager listeners from total consumption by the other.

Elvis and others notwithstanding, the raw authenticity of that music was unmatched in mainstream Rock until the mid-60s when the Beatles, the Stones, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Aretha Franklin, Bob Dylan, Laura Nyro, Jim Morrison and other greats emerged, all of whom acknowledged their debt to those earlier Rhythm and Blues pioneers. The synergy of the music and the social upheaval made it an exciting time.

.jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

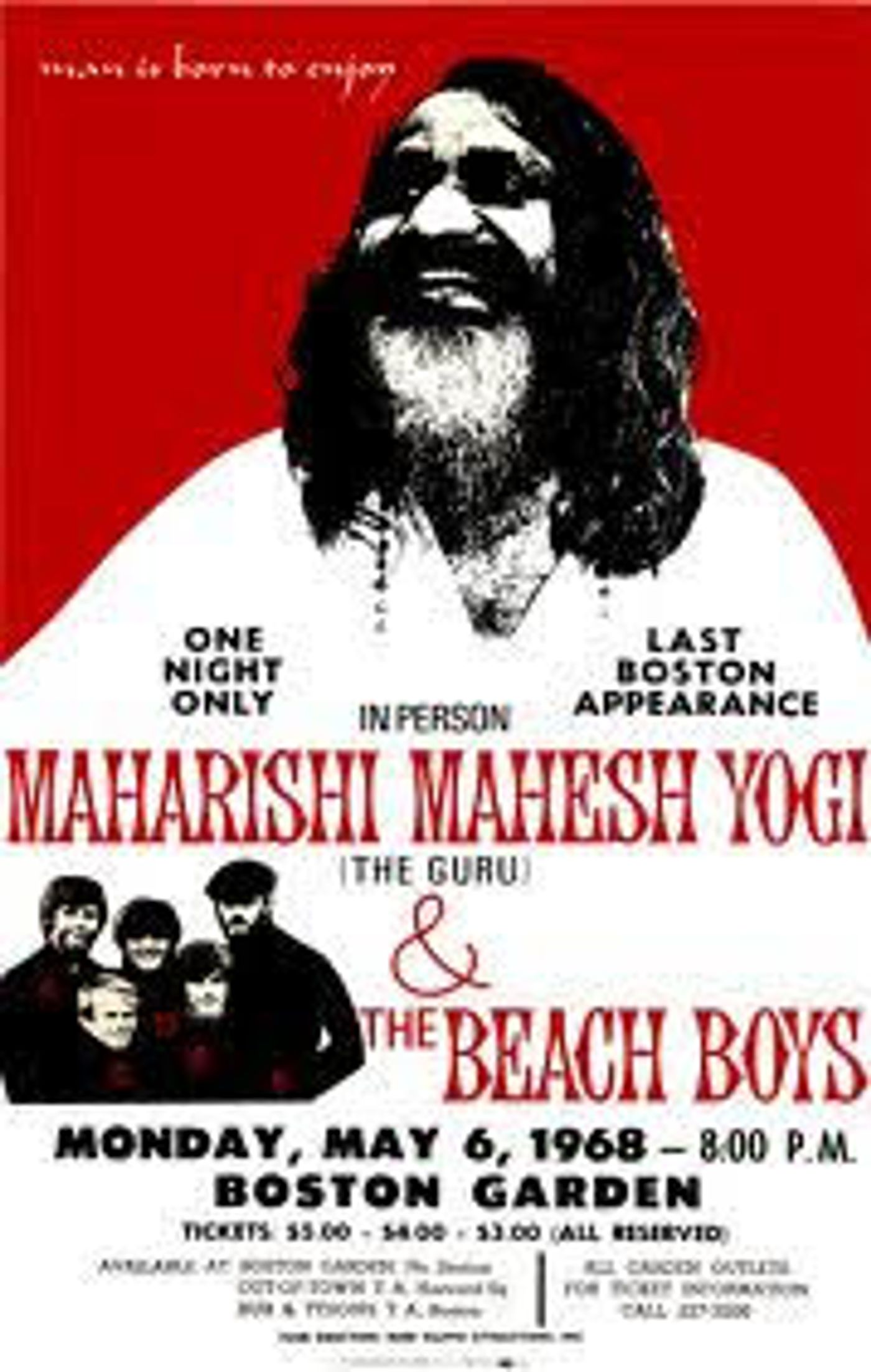

The Beach Boys had never been among my favorites---I thought of them as "the Republicans of rock." But in the spring of 1968 when Budd Filippo, our booking agent for The Fantasticks, asked me if I would be the press agent for a tour they were planning with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, I had open time and I jumped at it.

The Beach Boys were in a career low, and Maharishi had begun to fade from his media darling days as the Indian "guru" to the Beatles, Mia Farrow, The Beach Boys and others. With photos andheadlines of the hip and famous at his ashram in India, Maharishi had burst into the spiritual mythology of media hype, creating a worldwide market for similar gurus, endless lines of clothing and Indian music of the brilliant Ravi Shankar, among others.

Budd Filippo convinced me that combining The Beach Boys and Maharishi might provide a spark that would pull in an audience. And I convinced myself that Maharishi might have a valuable spiritual message for America.

Beach Boy Mike Love arrived in town dressed in beautiful Indian robes with a red beard and we toked out in a stretch limo for several days. He seemed slightly burned out but was straight forward and very likeable. We looked at Central Park and the Forest Hills Tennis Courts as possible future sites for what he envisioned as an "international festival of rock and love," headlined by the Beatles, the Stones and The Beach Boys. It was awesome to be with someone who could actually make that happen.

The tour with Maharishi would be produced by The Beach Boys themselves and, at this juncture, its success was critical to them. We hit it off and I was hired. But just as we were getting underway, the country exploded into a series of race riots and student protests, and the tour was delayed until things quieted down.

The Beach Boys manager, Nick Grillo, could be rough. On a conference call with Budd I asked to be reimbursed for some early expenses. He shot back with "Do you expect me to pay you every time you break wind?" I quietly put down the phone, left the office and walked home. Minutes later the money arrived by messenger.

.jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

Maharishi's Manhattan "ashram" was not a humble mud hut, but a posh townhouse on the East Side tended to by the young wives of New York's wealthy trendy. I had expected to sit on a mat and chat and pick up some spiritual enlightenment. But they weren't very chatty. I collected what little literature they had and left, thinking it must be a cash cow for someone.

I read the stuff and thought it was a "crock." David Cryer had been a student at the Yale School of Divinity, so I called him up and asked him to come have a look. He too was baffled. I called around to members of the press and student promoters I had come to know during The Fantasticks tour. Most of them viewed Maharishi as a hype and a goof.

I adjusted my approach. I went to the British American House, got myself a Nehru suit and grew a goatee. I ordered thousands of "Maharishi Coming" Day-Glo bumper stickers. I taped a "voice of God" radio spot interspersed with cuts from Beach Boy songs that advised listeners to "Bring a flower, bring a friend."

Nick Grillo agreed to let me spend a week with The Beach Boys to develop press material and I brought Henry Bigger, a photographer, as all of their photos were badly out of date. We were to join them in Nashville on the first stop of a tour with the Buffalo Springfield and the Strawberry Alarm Clock on April 4.

As I was about to go out the door, the Six O'clock News was interrupted by a devastating news bulletin. Martin Luther King had been assassinated in Memphis.

The flight to Nashville, jammed with press on its way to Memphis, brought home the enormity of the man and what this moment meant for the country. I flashed on his speech in a Memphis church only hours before when he chillingly foretold "I may not get there with you..." I remembered the march in Chicago. As I viewed the chaos in the crowded aisle of the plane I was overwhelmed.

.jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

Henry and I landed in Nashville and The Beach Boys road manager, Dick Duryea, one of two personable young sons of the actor Dan Duryea, greeted me with present reality. "Nick Grillo said to tell you if you ask for any money you're going right back home."

The Beach Boys and the other acts were badly shaken by the assassination. Nobody knew what to do. They did not perform that night. The next morning, as we were doing a sound check, tens of thousands of angry marchers passed by the auditorium loading door. The promoter evacuated us and we flew to Savannah where nothing was scheduled and we were hopefully out of harm's way.

On their private plane I began to know The Beach Boys while Henry snapped away. They were totally likeable, totally accessible but they seemed like unhappy children who had outgrown their toys and didn't know how to move on.

And if the Buffalo Springfield seemed desperately unhappy, the Strawberry Alarm Clock were the sub cellar of suicide. I thought, is this what it's like in rock and roll? Is this what all of us sit around and envy?

In a wacky synergy of the universe, I discovered that Alan Jardine's father was living in my parents' basement in Big Rapids where he was studying for a degree. I could see the tabloid headline: "Beach Boy Father Living in Basement." Dennis and Carl Wilson were just lovely and explained several times that their brother Brian wasn't with us because he was "busy at home writing songs." I left it at that. Bruce Johnston, who later wrote "I Write the Songs," seemed very ambitious and gave the impression that The Beach Boys would be a brief steppingstone in his career.

In Savannah, I arranged for us to go to a local television station and tape an "interview" with the group that could be dropped into local talk shows in the tour cities, most of which were unaccustomed to having such big-name guests. By allowing the Savannah station to broadcast it, we got the taping and twenty copies of the tape at no cost. I could feel Nick Grillo's approval radiating all the way from L.A.

As we began the taping, Mike Love asked me to stand behind the camera and "act silly to keep us all happy." I did my best, but they looked very down and depressed on the tape. I wondered what, if anything, Maharishi had really done for them---and how the reality on this tape could possibly work as a selling tool.

Several of the subsequent talk show producers were disappointed in the quality of the tape and used it on the condition that I would come on in my Nehru suit and introduce it. One live broadcast in Philadelphia was especially harrowing. I had to come running down a long ramp into a crowd of dancing teenagers where I was then interviewed by the very speedy host.

The New York dates were at the Singer Bowl (originally constructed for the World's Fair) and C.W. Post College. They were being handled by Connie de Nave, a veteran rock press agent, who was also handling the arrival of Maharishi at Kennedy Airport.

One week before the tour was to begin, we suffered a major setback. Seemingly, out of nowhere, rumors abounded that The Beatles had disavowed Maharishi and dropped him altogether. It was as if a bomb had been dropped. The local promoters and the fans were up in arms, to say the least. We took the position that it would "blow over," but my gut told me it was too hot not to be a mortal wound.

The downward spiral continued as Maharishi disembarked at JFK. Budd and Rosemary Filippo and I watched from above as he went through customs. Rosemary looked down at the bearded, unclean looking robed figure and cracked "Do you suppose they'll spray him?"

In the press room he was handed a wilted bouquet of what appeared to be dandelions, which fell to pieces the minute he touched it. As the jaded New York media fired away, he responded with a series of inarticulate giggles.

Immediately following the press conference, Maharishi informed The Beach Boys that he was due on location for a film in Israel the following Tuesday. The Beach Boys were fit to be tied. The tour was booked for 30 days. Nick Grillo arrived wearing an eye patch and under the circumstances didn't seem like a half bad guy.

The next night we opened in Washington, D.C. Tickets had not been selling like hotcakes. I presented myself to Maharishi as the tour press agent in his backstage tent.

"Oh, I am delighted," he giggled. "Were the pictures big? Is the reception favorable?" "Everything is fine," I lied. As we spoke countless teenage girls rushed into his dressing room one at a time while someone snapped their picture with Maharishi. They then ran out without saying "hello," "goodbye" or "thank you." Maharishi giggled.

"How is the atmosphere in Washington?" he inquired.

"Very tense," I replied. "In a few days there will be the Poor People's March."

"Why do they march?"

"Because they are poor."

"Better they should go to the marketplace and earn a dollar," he winked, and added, "It's very easy."

The Beach Boys, playing to half a house, did a well-received concert as the first half of the program. Then baskets of flowers and a divan chair were brought onstage for part two. An animal skin was laid across the divan, and Maharishi made his slow entrance from the back to scattered applause, heckling and a heap of curiosity.

He sat quietly on the animal skin in the lotus position until the heckling stopped and there was complete silence. He has them, I thought. He ran his finger down his beaded necklace and leaned into the microphone. "I feel such joy," he intoned in a high, squeaking Indian voice. The audience, expecting the rolling voice of God, exploded into two minutes of laughter and the heckling resumed. He was unflapped and once again waited.

He began to speak. "Love is a wave upon the beach of life. Life is a wave upon the beach of love."

I went out for a stiff drink.

The Washington Post panned the performance and called The Beach Boys "a yellowed page of rock history." The next afternoon was the date at the Singer Bowl. About 200 people and the same type of response. Saturday night they played to 20,000 at the Philadelphia Spectrum and, while I did not attend, I was reliably informed that 5,000 people walked out while Maharishi spoke.

The C.W. Post concert was outdoors the following afternoon and had a respectable attendance of several thousand including Peter Noone of Herman's Hermits. Stretch limos carrying The Beach Boys and Maharishi pulled up behind the stage and out of audience range. The Beach Boys got out, but Maharishi decided to go for a ride in the country and his driver floored the gas and peeled off in the opposite direction. "Don't worry, he'll be back," Mike Love said warily.

The C.W. Post concert was outdoors the following afternoon and had a respectable attendance of several thousand including Peter Noone of Herman's Hermits. Stretch limos carrying The Beach Boys and Maharishi pulled up behind the stage and out of audience range. The Beach Boys got out, but Maharishi decided to go for a ride in the country and his driver floored the gas and peeled off in the opposite direction. "Don't worry, he'll be back," Mike Love said warily.

As The Beach Boys finished their set to good response, Maharishi's limousine pulled up to the front of the stage in full view of the audience. My God, he is asking for it, I thought. The humble, disavowed guru stepped out of the stretch and onto the stage. The booing began as the car door opened. The hecklers were now out for blood. He tried to speak but couldn't finish a sentence. "What about Ringo?" "What about the Beatles?"

Mike Love took to the stage, imploring the crowd to be respectful. They were unrelenting. He said The Beach Boys would do more music if the audience would just listen to Maharishi, who did continue but cut his time short. The Beach Boys came back and played several encores.

On Monday, Maharishi departed for his film commitment in Israel with the full blessing of The Beach Boys. The balance of the tour was cancelled.

The Beach Boys suffered enormous personal hurt and accumulated great debt from this debacle. But, like the gentlemen they are, they set about to make reparations and repay everything, a process that would take several years.

Videos