Review: White Liberals Preach Diversity But Practice Privilege in Joshua Harmon's Hilarious ADMISSIONS

Innovative genius Norman Lear will forever be remembered for expanding the limits of what television comedy could do by bringing Archie Bunker, and his everyday brand of casual and not-so-casual bigotry, into American homes every week and holding him up to public ridicule.

(Photo: Jeremy Daniel)

But perhaps less remembered is the fact that Lear didn't let white liberals off the hook so easily. Archie's son-in-law Michael Stivic, for all his talk about supporting equal rights for women and minorities, was still in many ways a controlling husband, and in one episode, when he was passed over for a job in favor of a black colleague who he felt was less qualified, he expressed feelings of victimization for being white.

And then there was Maude Findlay who was so determined to use her privilege to help those who were targeted by bigotry that she tended to see people as skin colors (and in one episode, sexual orientation) instead of individuals with varying experiences and takes on life.

The spirit of Lear's critical commentary is very much in evidence at Lincoln Center's Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater in Joshua Harmon's frequently telling, often uproarious comedy Admissions, a play whose title suggests not only aspects of the plot, but also that we're getting a peek into the minds and emotions of white people who push all the required progressive buttons in public, but who react quite differently when leveling the playing field means losing some of what their skin has gained for them.

Sherri Rosen-Mason (a terrific turn by one of New York's smartest stage actors, Jessica Hecht) heads the Admissions department for a second-tier New England boarding school. One reason for its second-tier status is that when Sherri took on her job, the percentage of students of color was an embarrassingly low 6%, and she's been fighting for years against the school's reputation to bring that number up to a somewhat respectable level of 20%.

While it's been said that white people don't self-identify as white because race is not a part of their everyday lives, Sherri's awareness of racial differences appears to control every aspect of her life. She had "Moby Dick" removed from the school curriculum in order to reduce the number of white authors represented, her objection to the school cafeteria serving pizza was regarded as adversity to a Euro-centric menu and when speaking the names of Latinx students, her voice switches to an accent so overly-pronounced it can be regarded as cultural appropriation.

Her race-consciousness is especially evident in the opening scene, where she's stressing out over the lack of diversity shown in the photographs of the upcoming edition of the school's Admissions catalog, worried that potential students of color would notice barely anyone who looks like them in the campus life photos and assume they wouldn't be welcome.

"You're always race, race, race," complains an exasperated Roberta (sweetly matter-of-fact Ann McDonough) when Sherri points out the low percentage of students of color in what she has assembled.

Being in her 70s, Roberta comes from a time when "colorblind" was a popular term used to describe a preferred attitude of combating racism by simply not showing awareness of racial differences. The "melting pot" view of America which eventually gave way to the "beautiful mosaic."

Audiences can decide for themselves how they feel about Roberta's claim, "I don't see color... I'm not a race person. I don't look at race."

Roberta is especially confused about Sherri's problem with a photo of Perry, the son of Sherri's white friend Ginnie (Sally Murphy) and her biracial husband, Don. Though Perry counts as black in the school's diversity statistics, she's concerned that he doesn't appear as such in the photo.

Bristling when Roberta asks if she wants photos of students with darker skin, Sherri prefers to say pretty much the exact same thing by requesting photos of students who are "easily and readily identifiable as black or Hispanic."

"And let's stay away from any sports photos," she adds.

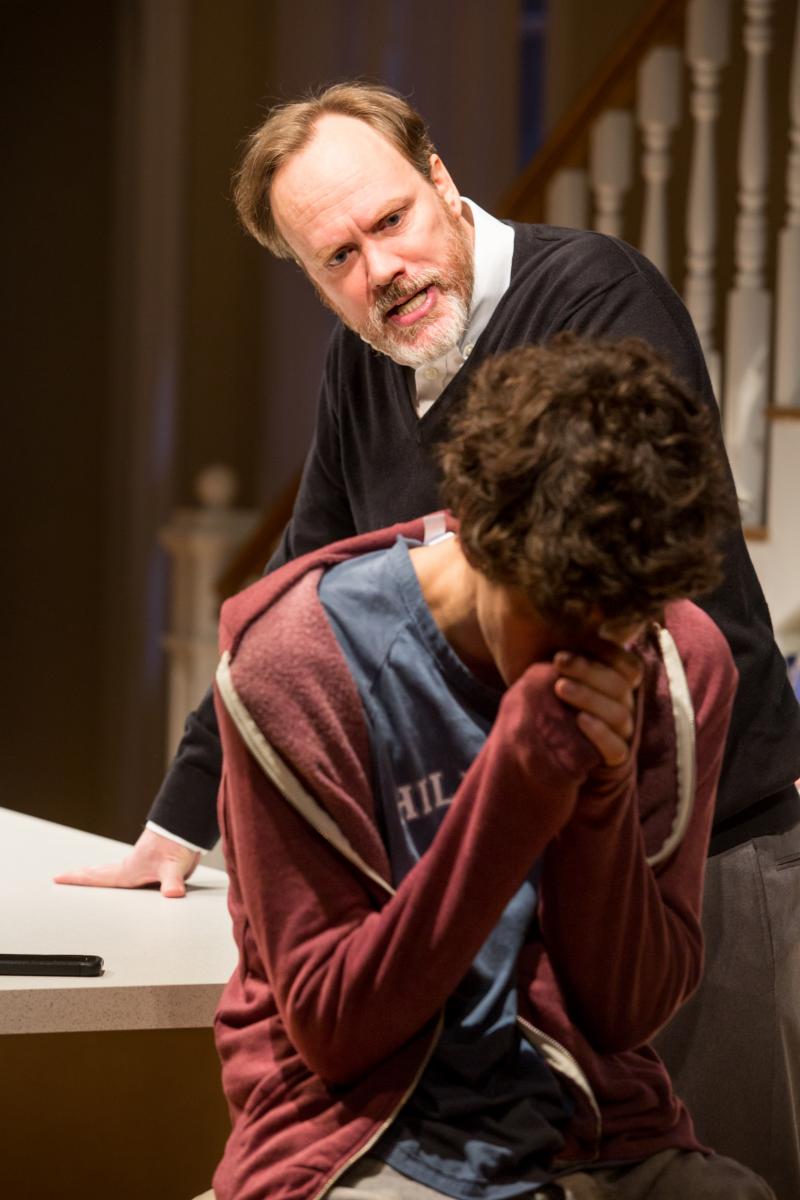

(Photo: Jeremy Daniel)

Later, when Sherri and Ginnie are making fun of Roberta ("She is so white," Ginnie mocks.), the subject of Perry's photo pops up and Sherri lies about the real reason why it was rejected.

Sherri's white husband Bill (Andrew Garman) is the school's headmaster and their son Charlie Luther (Ben Edelman), given the same middle name as Dr. King, and Perry are best friends. The two have both applied to Yale and Ginnie has brought over a cake from a controversial local baker ("Martin molested that child but it's Perry's favorite cake, what are you gonna do?") to hopefully celebrate both their acceptances.

Perry gets in, but it isn't until much later that night that a furious Charlie arrives home with the news that he was deferred. The wounded 17-year-old bursts into a lengthy screed about how his chances were decreased significantly because he was associate editor, not editor-in-chief, of the school newspaper; a circumstance he blames on what appeared to him to be an organized campaign to select a classmate, one he regards as a poor writer and an inadequate leader, to be the school's first female editor-in-chief.

"I get that there are entitled white men who assume they get a seat without having to do anything to earn it," he argues. "But I'm actually one of the people working really f-ing hard to earn a seat, and every time I get close it's like, ew! Not you! No one wants you here, fuck off."

This segues into his description of a classroom discussion triggered by a white student's objection to being assigned to read a book by Willa Cather because she finds it "soul crushing to read so many white books."

"I don't have white pride," Charlie screams, "but I don't hate myself."

He then explains how, when the son of a Chilean ambassador also expressed being sick of being assigned books by white authors, he pointed out how his skin color meant he was descendent from Spanish colonizers, who should be considered no less white than someone from Italy or France.

The kicker comes when Charlie points out how his Jewish grandfather, who escaped from the Nazis, couldn't get into an Ivy League school because of quotas, but now, because Jews are regarded as white, he's considered to be as privileged as the grandchildren of the Nazis who tried to exterminate his family.

At this point, Harmon has truly entered Archie Bunker territory, as Edelman's pitch-perfect manically deranged performance, coupled with the innocent ignorance expressed in the over-the-top writing, hilariously points out how Charlie sees only white victimization because he lacks consideration of historical context.

Bill is disgusted with his son and calls him a "spoiled little over-privileged brat," pointing out how, being a white male, he doesn't need Yale and will do fine going to Dartmouth or Duke.

But after Charlie runs up designer Riccardo Hernandez's symbolically high staircase leading up to his room, his parents are almost immediately plotting how they can use their connections to make things right for him, having no idea that their son, after eventually learning his lesson, will go to extreme measures to prove himself a sensitive white male ally, perhaps sabotaging his future in the process.

Under Daniel Aukin's sharp direction, Admissions presents an elevated reality addressing the real issue of white liberals (and/or male liberals) expressing themselves one way in public, but cautious to express their true feelings to those who they know they hold privilege over, for fear of being regarded as racist or sexist.

But the super-charged humor of the hypocrisy on display eventually evolves into a hopefulness that kids like Charlie are learning not to fear expressing their own truths in rational sharing ways before they manifest into destructive anger.

Reader Reviews