Review: LES MISERABLES, Sondheim Theatre

![]() Much of the conversation around the incoming of the revamped Les Misérables production to the West End has revolved around the revolve - or lack thereof.

Much of the conversation around the incoming of the revamped Les Misérables production to the West End has revolved around the revolve - or lack thereof.

But this slicker touring version (first seen in 2009, for the 25th anniversary) is a beautiful fit for Cameron Mackintosh's marvellously refurbished Sondheim Theatre, and the show's indelible score and stirring human drama are, if anything, showcased more strongly than ever.

That's not to diminish the incomparable development work of Trevor Nunn, John Caird, the RSC and the original creative team - much of which still forms the backbone of this Les Mis. But directors Laurence Conner and James Powell releasing the show from the dominating revolve allows for a brisker, spryer production, one in which individuals have more freedom to explore.

Still, the presence of numerous Les Mis veterans means there's a sense of continuity, including Bradley Jaden reprising his Javert, Carrie Hope Fletcher trading in Eponine for Fantine, and Lily Kerhoas and Shan Ako bringing their (respectively) Cosette and Eponine from the recent staged concert to the main West End production.

Chief among them is our new Jean Valjean: Jon Robyns has previously played both Marius and Enjolras, and, in our interview with him, teased taking on even more parts in future. But let's hope he stays as Valjean for a good long stint first, since this is a gripping take on the iconic lead.

Victor Hugo's wronged hero can sometimes come across as a little too saintly and/or stately. No such danger here: Robyns tears into the character, his Valjean raw and animalistic initially, and retaining some of that volatility throughout. It gives the whole show a welcome jolt of energy.

He and Carrie Hope Fletcher's Fantine are a match not in suffering, but in ferocity; even at their lowest point, both keep fighting. Fletcher's performance is wonderfully direct and natural, her "I Dreamed A Dream" combining powerhouse vocals with a heart-stopping confessional quality.

It's an example of how this relatively unencumbered staging showcases superb character work. Fletcher and Robyns create tiny charged moments - from their initial meeting at the factory, that agonising missed opportunity to avert disaster, through to the feverish deathbed promise. Later on, Robyns' exquisite "Bring Him Home" feels entirely organic, and all the more moving for it.

He also plays brilliantly off Jaden's equally committed Javert. Their entwined fates are clearly drawn here, with Robyns' Valjean growing in certainty, faith and wisdom, while Jaden's Javert goes from coolly contained to an unravelling, lost soul - supported by thoughtfully pitched vocals that express first crisp authority and later wild, all-consuming despair.

Shan Ako is a refreshing, savvy Eponine, putting her firm stamp on the role - and in particular a show-stopping, gospel-tinged "On My Own" - while Ashley Gilmour's Enjolras has rock star charisma, through perhaps lacks the gravitas of a revolutionary leader. Kerhoas has the right sweet soprano for Cosette, but she and Harry Apps's rather bland Marius are the weak links here dramatically.

However, there's stellar support from an almost unrecognisable Josefina Gabrielle and the recently drafted Ian Hughes as the Thénardiers. Via detailed physicality, distinct vocals and lightning-fast exchanges, the pair provide a devilish vaudevillian double act - laughter edging into bleak nihilism.

Credit, too, goes to Richard Carson's particularly nasty foreman, Rodney Earl Clarke's fervent bishop, and Billy Jenkins' outstanding Gavroche - swaggering, undercutting some of the solemnity with sly wit, and dancing around the Paris back streets with practised ease. Thanks to Jenkins, his fate is the one most dearly felt.

The close-knit ensemble and excellent orchestra, under the baton of Steve Moss, help deliver Claude-Michel Schönberg's epic score - and some of the dust is blown off it by Stephen Metcalfe, Christopher Jahnke and Stephen Brooker's updated orchestrations.

While giving us a tour of the theatre, Mackintosh explained that it was his learning that Victor Hugo painted as well as wrote that partly inspired this new production. Matt Kinley's set design is a gorgeous theatrical response to Hugo's art, giving us something between naturalistic scene-setting and expressionistic sensitivity; when Valjean sings of the night closing in, the sky around him seems to melt.

Effective, too, are the video projections from Fifty-Nine Productions and Finn Ross - although a section in the sewers extends a little too long. And though this version lacks the sheer spectacle of John Napier's revolve powering a giant barricade, there are still striking moments, like the arrival of two tenement towers teeming with destitute people.

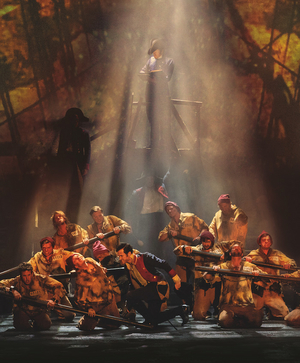

But the real star of the show now is Paule Constable's lighting, which seems to get at the very core of the material's spirituality. Shimming shafts of light capture awe-inspiring moments like the departure of Fantine's spirit or the martyring of Gavroche, or punctuate action like bullets flying on the barricade. Constable's work draws together the mystical, painterly elements into a whole, both honing in on the very human story and elevating it into a religious experience.

That's what makes this such an enduring show: the very relatable questioning of what a life is worth, and what makes life worthwhile, alongside meaty - and still resonant - dramatic fare like entrenched inequality, harrowing poverty, sexism, justice, faith, and the power of redemption.

This may be the Sondheim Theatre, but God's work is unlikely to be performed here any time soon. Do you hear the people sing, and sing? Oh yes - the Les Mis flag will be flying in the West End for years to come.

Les Misérables currently booking at the Sondheim Theatre until 17 October

See more photographs of the cast and theatre here

Photo credit: Michael Le Poer Trench

Reader Reviews