Review: Keith Hamilton Cobb's Breathtaking Exploration Of American Theatre's Intrinsic Racism, AMERICAN MOOR

A black actor, a white director, and a character named Othello

A bit over 400 years ago, a white Englishman named William Shakespeare scripted a play based on a story by a white Italian known as Cinthio about a Moorish general serving in the Venetian army, who is regarded as an outsider by his white colleagues because of his skin color.

Named Othello, he is undoubtedly the most famous character of color depicted in English-language drama. But while records do exist of actors of color playing the role during the drama's first three centuries, the overwhelming majority essaying the part have done so with dark makeup applied to their faces.

Which means that for hundreds of years, the interpretive traditions and popular preconceptions about Othello have been introduced and nurtured by white artists to satisfy the tastes of predominantly white audiences.

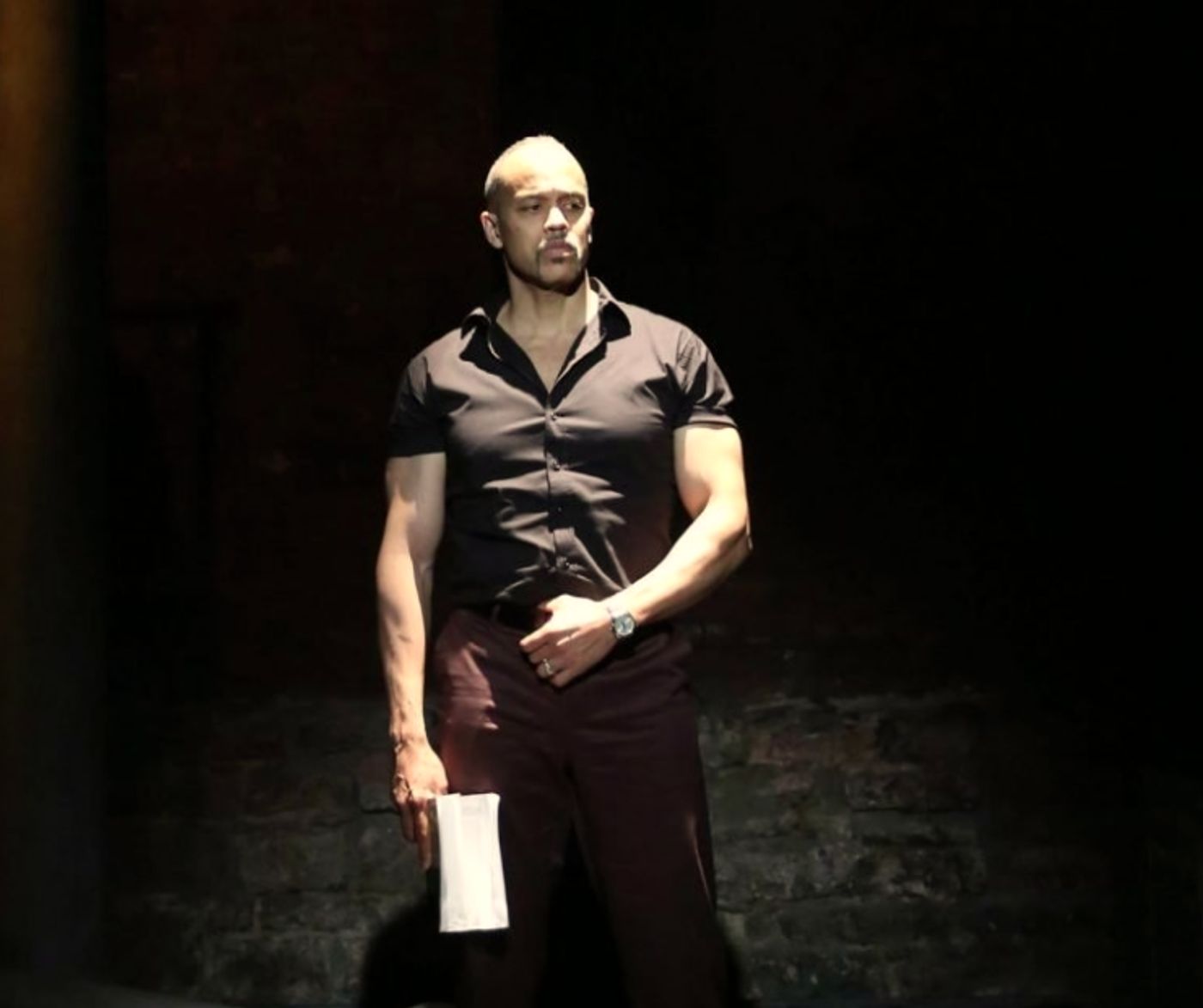

So, as in the case with playwright/performer Keith Hamilton Cobb's breathtaking theatrical exploration, American Moor, when an African-American actor approaches the character of Othello, he brings with him a more personal understanding of the man's situation, and how Othello's reaction to the situation may contrast with the expectations of white colleagues and customers, going beyond the knowledge of Shakespeare, Cinthio and this theatre critic.

Or, as Cobb's semi-autobiographical character, also named Keith, puts it, "...purely by virtue of being born black in America, I know more about who this dude is than any graduate program could ever teach you."

That line is part of the internal monologue going through the actor's brain as he auditions for an unbearably smarmy white director's production of OTHELLO. But first, we get a bit of personal background.

As a young actor at the start of learning his craft, Keith finds no help in classes focused on method acting ("As I recall, we sat around a lot being all still and quiet-like waiting for some external stimulus to enter our bodies and compel us to act.") but feels an instant connection to the words of Shakespeare.

Quoting some choice insults from HENRY IV, PART 1 ("...he made me mad / To see him shine so brisk and smell so sweet / And talk so like a waiting-gentlewoman / Of guns and drums and wounds. God save the mark!"), he recognizes, "I could say that, as well as anyone, and infused with every ounce of my glorious African-American emotional arrogance, it would sing."

And though a teacher suggests he work on Aaron, the Moor, in TITUS ANDRONICUS or Morocco of THE MERCHANT OF VENICE. ("Pick something you might realistically play!") Keith feels strongly about acting out Titania's "forgeries of jealousy" speech in A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM, commenting to the audience that though the adamance found in that and other speeches by many of Shakespeare's leading players is something he finds "swollen with all of my most honest African-American energies," non-black people tend to be uncomfortable to see such adamance displayed by a black man.

This becomes apparent when the director auditioning him to play Othello (Josh Tyson, seated in the audience throughout the play) asks him to soften up his performance of a confrontational scene, wanting Othello to charm rather than challenge the white people of the senate.

.png?format=auto&width=1400)

Though the actor is willing to placate the booksmart, condescending director ("What Shakespeare was trying to say here is perhaps...") for the sake of getting cast, his internal monologue expresses disdain for the disrespect given to his experience-based interpretation.

As the stories told and the actors seen on New York's stages have been increasing in diversity, a major issue of discussion has been the continued majority of white people in attendance, and the concern that productions are showing African-American characters, in particular, through a lens that is deemed comfortable for white viewers. While this issue is not discussed in American Moor, the play certainly brings it to mind.

Director Kim Weld, who is white, writes in her program notes that American Moor "asks us to do the great work of empathy."

"Acting is reacting," is a lesson a drama teacher tries teaching the play's protagonist. But to react, one must first listen. Really listen.

Reader Reviews

Powered by

|

Videos