Review: Joshua Henry Thrills in Jack O'Brien's Drastically Edited Version of Rodgers & Hammerstein's CAROUSEL

During the first half of the 20th Century, there was no artist as important to the development of American musical theatre from strictly light entertainment to a legitimate dramatic art form that addressed controversial issues and exposed the country's uglier norms than bookwriter and lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II.

Teaming with composer Jerome Kern, SHOW BOAT shocked 1927 audiences with its symbolic theme of America's racial divide depicted as an ever-flowing river. Teaming with Richard Rodgers and Joshua Logan, SOUTH PACIFIC spelled out its message that bigotry is an acquired behavior, rather than a natural human instinct, with what was considered a hot-button song in 1949, "Carefully Taught." In 1951, THE KING AND I asked audiences to question presumed superiority of western culture over nations they might regard as primitive or barbaric.

Now, of course, Hammerstein was a white man in a time when those who weren't white men received extremely limited opportunities to write books and lyrics for Broadway musicals. And though he may have been Broadway's leading progressive thinker during his lifetime, with the, albeit too slow, expansion of racial and gender diversity in American theatre, aspects of his work - as well as the work of other well-meaning theatre writers of his time - are often accused of being oppressively patriarchal and Eurocentric in retrospect.

Take, for example, Carousel. The 1945 sophomore effort by the team of Rodgers and Hammerstein is an Americanized version of Hungarian playwright Ferenc Molnar's 1909 drama LILIOM, reset to a Maine coastline town. Judged solely on the quality of its expertly-crafted book, its captivating music and the emotional poetics of its lyrics, Carousel must be regarded as one of the art form's highest achievements. But it's the way that Hammerstein presents its subjects of spousal abuse and redemption that has, in many opinions, not aged well and has caused the musical to be regarded as problematic for contemporary audiences.

Sexy and charismatic Billy Bigelow, who barks for a carnival carousel and - in a symbolic detail, helps women on and off the attraction - is a local celebrity and the object of every young lady's bad boy fantasy. A veteran of the Coney Island scene, it's rumored that he's skilled in romancing innocent girls and stealing their money.

Perhaps that was his intention when he put his arm around millworker Julie Jordan while seating her on a painted wooden horse one evening, a move that flew his employer, Mrs. Mullin, into a fit of jealousy. When Billy scoffs at Mullin's insistence that Julie be barred from the carousel, she fires him. When Julie ignores her boss' advice that she forget about Billy and go back to her room at the mill's boarding home, he fires her.

With the rugged and uneducated Billy fascinated by this seemingly fearless girl, and the prim, but adventurous Julie coyly planting ideas into his head, the two partake in the most exquisitely-written scene that musical theatre has to offer, showcasing the teasingly tentative ballad, "If I Loved You."

When we next see the pair, it's three months into their marriage and the selfless Julie is so worried about the stress her husband is feeling because of his inability to get a job, that when she confides to her best friend Carrie that Billy has hit her, she expresses sympathy for the pain he must be feeling that drove him to it.

And that's when Carousel starts becoming uneasy; with the realistic depiction of a woman who will defend her abuser despite (and Hammerstein makes this clear) the fact that everyone else regards his behavior as unacceptable.

When Julie becomes pregnant, Billy, desperate for money, decides to partake in a robbery with his whaler buddy, Jigger. But when the job is botched, he commits suicide rather than be arrested. Greeted in the afterlife by a gentleman called the Starkeeper, he's told that he can enter Heaven only by fixing some of the mess he caused.

A futuristic look at his daughter, Louise, shows a sullen teenager whose low self-esteem makes her an easy target for boys, like Billy once was, looking to take advantage. An appearance by the widowed Julie includes her passing along to her daughter the belief that it's possible for someone to hit you, and you never feel it at all; a sentiment that seems to suggest a sensation many abuse victims have described where they feel removed from the violence as it's happening; experiencing it as an observer, rather than as a target.

The deceased Billy knows it's he who helped Julie upon the carousel's cycle of abuse, and he's now determined to help Louise off of it.

That line from Julie to her daughter has been cut from director Jack O'Brien's revival, which includes numerous other edits. The main intent seems to be to tone down Julie's acceptance of her abuse and, utilizing a major revision in the final scene, making Billy a more active participant in changing the direction of his daughter's life.

As scripted by Hammerstein, the musical opens with a pantomime and dance sequence set to Rodgers' sumptuous "Carousel Waltz," contrasting the giddy atmosphere of the carnival with Julie's first exposure to Billy's dangerous allure. O'Brien, however, sets the first part of the ballet in a purgatory inhabited by the Starkeeper.

As originally written, the Starkeeper doesn't appear until the musical's final scenes, but with the very fine classical actor John Douglas Thompson playing the role, it has been expanded to include moments where he's silently observing Billy. It gets a little hokey, though, when O'Brien has him standing right next to the fellow, who doesn't see him. When the production reaches the Starkeeper's scripted scenes, Thompson exudes a warm, folksy wisdom.

Billy, for reasons that aren't clear, is up in purgatory too in that opening moment, but soon we're back in coastal Maine.

This production serves as a sensational Broadway debut for the 30-year-old choreographer Justin Peck, currently resident choreographer at New York City Ballet. The highlight of this opening waltz is the representation of a carousel by a circle of pairs, with men simulating the movement of the wooden horses as the women ride upon them.

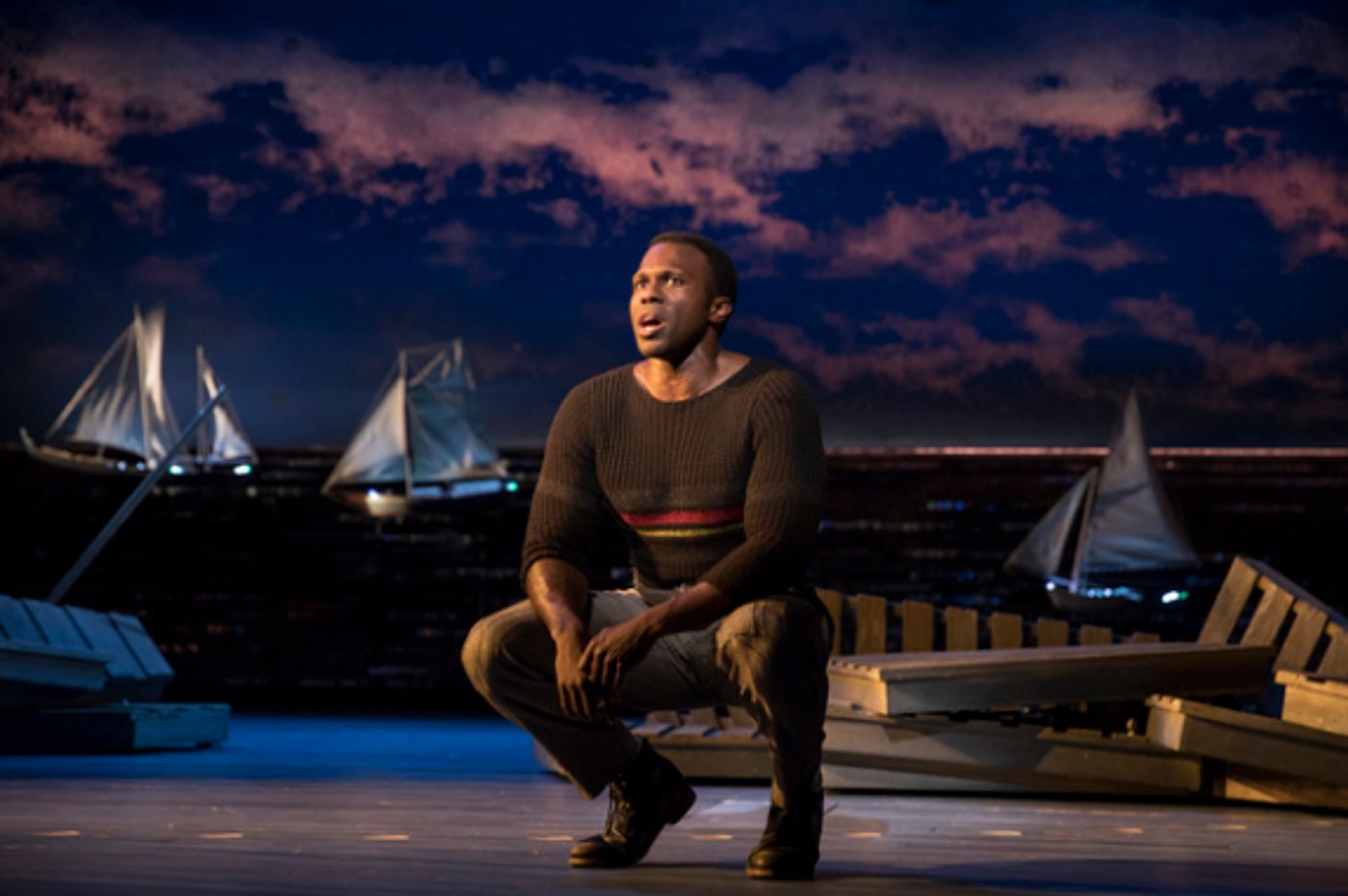

It also serves as what might be regarded as a breakout performance by Joshua Henry. Much-admired for his Broadway work in THE SCOTTSBORO BOYS, VIOLET and SHUFFLE ALONG, Henry is in fully command of a demanding leading role. His Billy is one who lives on his good looks and a menacing glare that can control any conflict. Settling into a marriage and being responsible for a family is a huge step out of his comfort zone, but, in his first scene with Julie, you can see his fascination with her pulling him in. His touching rendition of "If I Loved You" displays a tentative opening of his heart.

But Henry's Billy also displays moments of angry frustration making him seem capable of the kind of violent fits a child may throw when he doesn't have the words to communicate his emotions.

Left alone, however, he communicates them wondrously in the lengthy "Soliloquy," the epic musical moment when Billy contemplates his future as a father and then panics at his lack of preparedness for the position. (As with many productions of Carousel, the "When I have a daughter..." section has been cut.) Henry beautifully plays a mixture of pride, bewilderment, tenderness and self-doubt, building to a powerful vocal climax that insures he will participate in the robbery for his family's sake.

Leading lady Julie, played by Tony winner Jessie Mueller, is a significantly smaller role, and two major directorial choices make it seem even smaller. The first involves Julie's disappointment when Billy initially tells her he's not interested in joining her for a big clam bake. In a scene directly following "Soliloquy," she's delighted to see that he's changed his mind, not knowing that his reason for attending is to help him have an alibi after he commits the robbery. Having the first act end with Julie hopeful that she can save her marriage, with the audience knowing the truth, stresses her tragic side of the story. O'Brien cuts the entire scene and ends the act with "Soliloquy."

The second comes with Julie's second act ballad, "What's The Use of Wond'rin?," where she dutifully resigns herself to love her man no matter what. Perhaps to make sure the audience knows that her sentiment is meant to show Julie's wounded state, and is not a recommendation, the character is upstaged by Carrie (played by Lindsay Mendez) and by her cousin Nettie (opera star Renee Fleming in her second Broadway outing) who stand nearby with judgmental expressions on their faces. The director also adds Nettie to the song's second chorus, giving her solo lines that, in a new context, express disappointment in Julie's point of view.

Earlier in the show, Fleming appears to be having a grand time leading the company in the rousing anthem of summertime's sexual awakening, "June Is Bustin' Out All Over." Her second act solo of the musical's inspirational hymn, "You'll Never Walk Alone," mixes warmth and majesty.

(Photo: Julieta Cervantes)

A talented clown with sizable serious acting chops and a killer belt, Mendez is a broadly comic delight in a role that, because of cut material, has been diluted of its dramatic content.

As the musical begins, Carrie has accepted the proposal of fisherman Enoch Snow (Alexander Gemignani, a sturdy presence with a lovely tenor), but before we meet him, the audience gets a taste of how the rambunctious free spirit can stand up to the demands of any man in a musical scene with some hard-working clam diggers. The scene has been cut, thus the audience doesn't see the contrast when she willingly complies to follow Enoch's unswerving plans to expand his sardine business and spend the first decade of their marriage producing eight children.

Also cut is Enoch's song "Geraniums in the Winder." Sung when he temporarily breaks up with Carrie after mistaking her interaction with Jigger to be flirtatious, it's a description of the married life he envisioned, which is a romanticized version of the control he expects to have over his wife. Jigger would normally react with his song, "Stonecutters Cut It In Stone," commenting how "There's nothing so bad for a woman as a man who thinks he's good," but that, too, has been deleted.

Which is a shame, because ballet dancer Amar Ramasar is quite terrific as the sardonically-humored Jigger. Naturally, he's featured in a big dance number, leading his fellow whalers in an excitingly athletic hornpipe.

Peck's final choreographic gem of the evening is a pas de deux between Louise (Brittany Pollack) and a fairground boy (Andrei Chagan) who romances her briefly, leaving after he gets what he wants.

While those, like this critic, who prefer to see theatre pieces performed with the text the authors wrote, will wince at the many changes, Carousel is still made up of ravishing material, and what remains still provides enchantment, thrills, great drama and solid laughs in a well-performed and vibrantly choreographed production.

Reader Reviews

Powered by

|

Videos