Review: John Lithgow Recalls Telling Tales With His Father In STORIES BY HEART

"So what the hell is this?!," John Lithgow quizzically quips to the audience at the outset of his Broadway solo stint.

Well, on the surface, STORIES BY HEART is a very fine actor - a major theatre star since winning his first Tony Award just 23 days after making his first-ever appearance before a Broadway audience - acting out short stories written by two very fine 20th Century scribes who were once familiar faces around Times Square: Ring Lardner and P.G. Wodehouse.

But it's also a loving remembrance of his father, Arthur Lithgow; a Broadway actor himself, who, beginning in his mid-thirties, founded and ran a succession of summer Shakespeare festivals in Ohio.

"My father produced every single one of Shakespeare's plays," the actor proudly announces. "And not just the famous ones. Plays like KING JOHN, TWO NOBLE KINSMEN and TITUS ANDRONICUS! That's the one where the queen is tricked into eating meat pies made out of her own two dead sons. I saw that when I was about eight years old."

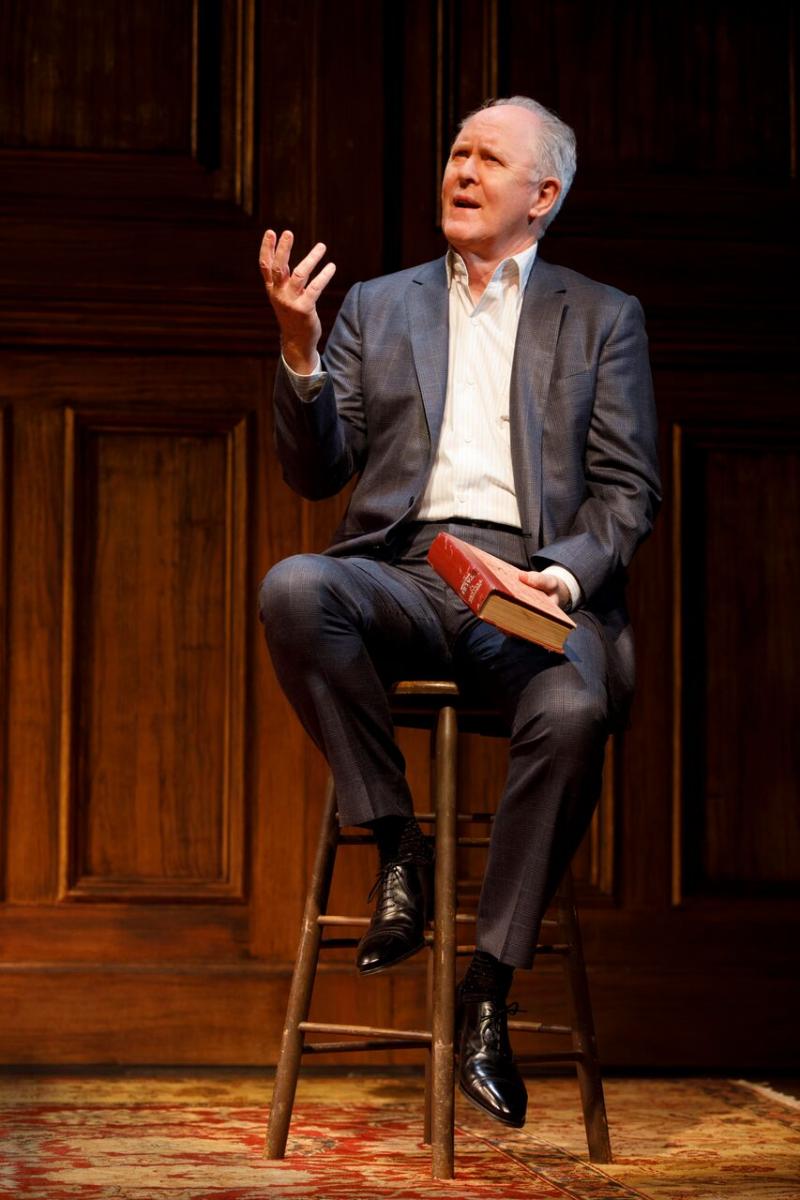

The Lithgow family Bible, so to speak, was a collection of short stories selected by W. Somerset Maugham and published in 1939 under the title "Tellers Of Tales." The actor brings the book onstage with him, and it serves as his only prop in director Daniel Sullivan's staging.

In the first act, Lithgow demonstrates how his father would read and perform selections of the book as a family bonding ritual, encouraging a love of storytelling that would inspire the young lad to be an actor.

The example he uses is Lardner's "Haircut," a twisted view of Americana small town living where a neighborhood barber chats to his customer about how dull things have been since the death of a town joker. Recalling the fellow's antics brings about darker realizations. It's a subtle piece that Lithgow performs with a folkiness that gradually becomes uneasy as he mimes the business of combing and clipping.

The second act takes place many decades later, with Arthur Lithgow in poor health after a dangerous operation. This time it's the son who takes on the task of reading and performing, in an attempt to ease his father's pain and perhaps inspire the return of his hearty laugh.

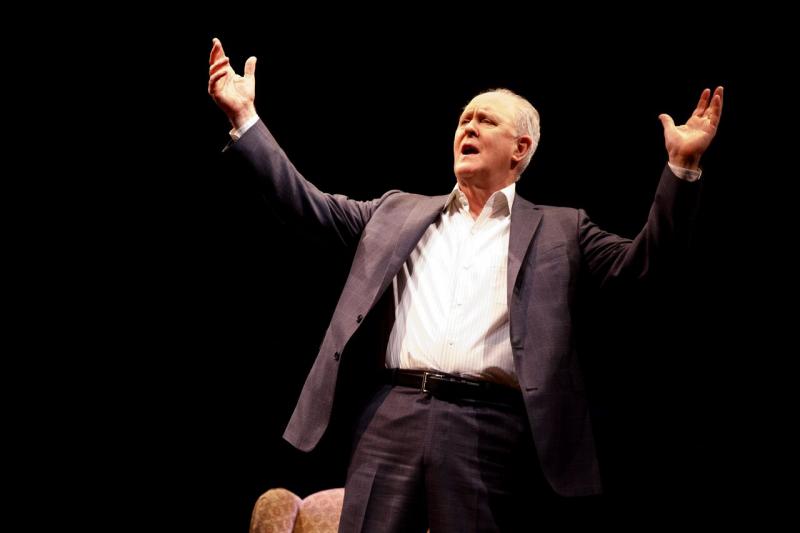

The story is Wodehouse's "Uncle Fred Flits By," a broad bit of British silliness that allows Lithgow to play an assortment of madcap characters.

And it's during this second telling that it becomes apparent that the words provided by Lardner and Wodehouse are simply devices used to tell the more universal story of the piece; the reversal of the parent and child roles as the son gathers the skills he learned as a captivated audience member being regaled by his father at bedtime and applies them to his new position as the caregiver trying to keep dad happy and comfortable as he prepares to take his final bow.

And it's that sweet bit of closeness and admiration that gives the presentation of these stories so much heart.

Reader Reviews