Review: Broadway's Day of Reckoning Has Arrived with PASS OVER

Pass Over by Antoinette Chinonye Nwandu is now playing at the August Wilson Theatre.

While I promise to not gush over the magic of in-person theater every review, I would be remiss if I did not take a small moment to wax poetic about the joy I felt deep in my soul when I walked into the August Wilson Theatre and sat in a velvet seat once more. Every night since previews began, when stage manager Cody Renard Richard begins his pre-show announcement, the audience bursts into thunderous applause--and for some of us, into tears. This pandemic may not be over, but we are back seeing in-person theater on Broadway, and that is itself is a cause for celebration.

I could go on and use cliché lyrics from "As If We Never Said Goodbye" to describe what it felt like to sit down to watch Antoinette Chinonye Nwandu's Pass Over, but I feel the lyrics would not be accurate. Pass Over is not the Broadway of yesteryear. This is a new Broadway, both glistening and openly revealing darkness underneath. It is not complacent, uncritical, or simply nostalgic. Perhaps we have finally said goodbye to one incarnation of the Great White Way, and here Pass Over ushers in the next era, baptizing Broadway anew.

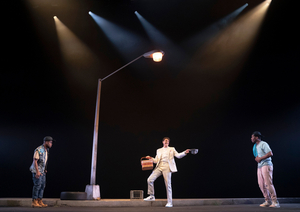

Nwandu's Pass Over is a brazenly political play that combines Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot and the Biblical Exodus story with centuries of systemic racism, rampant police brutality, and the Black Lives Matter movement. It takes place in "the (future) present, but also 2021 CE, but also 1855 CE, but also 1440 BCE" on "the river's edge, but also a ghetto street, but also a desert city built by slaves (and also the new world to come ((worlds without end))." Wilson Chin's minimalist set design provides us with a bare street light, a nod to Godot's tree. The play explores, thematically and literally, various types of cycles--in particular the cycles that Black people are trapped within under systems of white supremacy. These systems and cycles have been around, as the play reminds us, since Biblical Egypt, continued on in slave plantations, and are very much still present today.

Moses (John Michael Hall) and Kitch (Namir Smallwood) want to get off their city block; they want to pass over on to bigger and better things. They list the top ten things they imagine in their promised land, including comfort foods like collard greens and pinto beans, class markers like champagne, caviar, new air Jordans, and a Ferrari, womanly companionship, revived loved ones murdered by police, and bright red tulips. They want to reach their full potential--a loaded phrase, especially for Moses, who was the Sunday school favorite and whose name comes with baggage and expectations of its own.

Just as in Waiting for Godot, their desires for change seem futile, as Moses and Kitch stay trapped on their block, repeating the same conversations with each passing day. The cyclic monotony is only interrupted by two white characters, a seemingly benevolent man lost with a picnic basket and a police officer (both played by Gabriel Ebert). In both instances, the white men invade Moses and Kitch's space in ways that feel like violations. Several times while they are alone even, lighting shifts (designed by Marcus Doshi) and they freeze with their hands up, demonstrating the disruptive terror of police surveillance and the perpetual threat of violence.

Just as in Waiting for Godot, their desires for change seem futile, as Moses and Kitch stay trapped on their block, repeating the same conversations with each passing day. The cyclic monotony is only interrupted by two white characters, a seemingly benevolent man lost with a picnic basket and a police officer (both played by Gabriel Ebert). In both instances, the white men invade Moses and Kitch's space in ways that feel like violations. Several times while they are alone even, lighting shifts (designed by Marcus Doshi) and they freeze with their hands up, demonstrating the disruptive terror of police surveillance and the perpetual threat of violence.

Ebert's seemingly well-meaning white man who is just passing through is kind but clueless, a ceaseless slew of microagressions. After admitting he was unaware of the high number of Black people killed by police in the neighborhood he says "it isn't safe out here, I mean you fellas should do something. Call the poli--or, or, I don't know do something" and "if I were in your shoes gosh I'd be terrified" (tinged with even more painful irony by the fact that he is wearing pristine air Jordans). As cringe-worthy and gasp-inducing as several of his lines are, it is Ebert's return as the police officer which creates the true sense of terror.

Pass Over premiered at Steppenwolf Theatre in 2017 where it was filmed for Amazon, and had another production at Lincoln Center in 2018. In these iterations, the play climactically ended with Moses being fatally shot, and Ebert delivering a Raegan/Trump-infused monologue, leaving the audience to exit in stunned silence. However, after the terrifying year we have had following George Floyd's death and the racial reckoning it inspired, Nwandu decided she needed a different ending. Instead of witnessing yet another

murder of an innocent Black man by a white man, we are treated to an Afro-futurist vision in which Moses and Kitch live, Moses performs an exorcism on the cop, and their promised land opens up. It is a utopic jungle "somewhere over the rainbow" where the sun's coming up and they are free--where they can pass over. The cop is allowed to enter the paradise, but Moses instructs him "if you comin, gotta leave all dat behind," having him shed his gun, badge, and uniform. Nwandu's vision of the promised land is one of racial equality and police abolition.

This new final section can at times be a bit heavy-handed and preachy--however, (mostly white) Broadway audiences are in desperate need of an education on these themes, so it is more than justified. Also, it is fitting for a show so steeped with religion to be "preachy"--preaching is part of the play's theological dramaturgy. Danya Taymor, a star of off-Broadway (Heroes of the Fourth Turning, "Daddy") here makes her Broadway debut, handling a complex play with finesse, striking just the right note of righteously didactic. Hill, Smallwood, and Ebert combine to expertly navigate the shifting tones of the piece, juggling hilarious comedy, whimsical Beckett-style absurdism, terrifying tragedy, and manifesto/sermon-like speeches.

During the shutdown, there was a great deal of conversation about how Broadway needs to change; Pass Over is the embodiment of that change. It is exactly what Broadway needs to be. If we can follow the lead of this production, Broadway can pass over into something different, something better, something more equitable and diverse, something more political. If Broadway is to survive, it must keep up with the times. Pass Over offers a model of how it can do that. It is an extraordinary beacon, a proof that, in Moses' words, "dis shit's changin now."

Reader Reviews