Review: Bill Irwin's ON BECKETT / IN SCREEN Takes A Clown's-Eye View Of The Modernist's Words

His Irish Rep solo performance is adapted for home screens.

"I am not a Beckett scholar," Bill Irwin advises viewers at the outset. "Mine is an actor's relationship to this language. By which I mean the deep knowledge that comes from committing words to memory, and speaking them to audiences."

But Bill Irwin, who rose into the public consciousness during the 1980s with the emergence of New Vaudeville, is also an accomplished clown, and it is through the great clown traditions, he explains, that he views everything.

"They are like a lens to me."

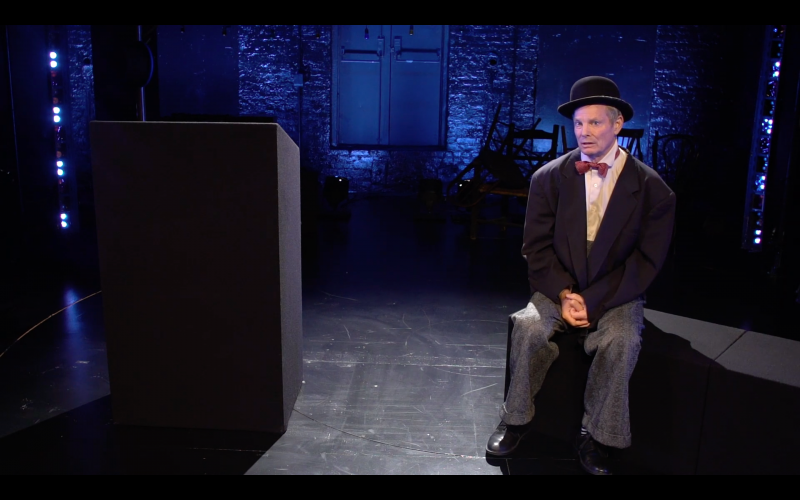

Two years ago, on the stage of New York's Irish Repertory Theatre, Irwin offered a peak through that lens with his solo performance piece ON BECKETT, which has now been adapted for the COVID Era (Is that an official theatrical movement now?) as ON BECKETT / IN SCREEN, available for viewing at IrishRep.org.

You'll pardon me if I mention the pangs of nostalgia I felt when, at the presentation's commencement, the star is seen entering through that venue's West 22nd Street doorway, crossing through the lobby and walking that thin aisle between the seating risers and the restrooms on his way to the stage. Though the theatre is empty (social distancing procedures for the crew were in place), the live experience is capably substituted with the intimacy provided by selective close-ups, via Irwin and M. Florian Staab's co-camera direction.

"Is Samuel Beckett's writing natural clown territory?," he asks. "That is a question we will pursue and examine."

Of course, as one would expect, there would be no reason for us to witness Irwin's examination if the answer was "no," so he proceeds, through a very entertaining combination of lecture and performance, to interpret the infamously tragic-comic, sometimes frustratingly indecipherable, works of the Irish literary giant who wrote his major works in French (and then translated them back to his native tongue) through the traditions of baggy pants and physical comedy, blending their observations on the human condition.

Three performance moments are excerpts from "Texts For Nothing," Beckett's 1950 assortment of monologues spoken by anonymous characters which avoid any recognizable trajectory.

"How long have I been here, what a question, I've often wondered. And often I could answer, An hour, a month, a year, a century, depending on what I meant by here, and me, and being, and there I never went looking for extravagant meanings, there I never much varied, only the here would sometimes seem to vary. Or I said, I can't have been here long, I wouldn't have held out."

Rather than fill in the missing specificity, Irwin's performances give the impression of an artist unhesitatingly navigating through the writer's language, willing to go wherever the words take him.

Beckett's novels "The Unnameable" and "Watt" are entered into the discussion, but the bulk of Irwin's concern pertains to WAITING FOR GODOT, a play he's performed in many productions. Along with the debate over the proper pronunciation of the play's name, there's considerable exploration of the author's stage directions, particularly a moment where it's specified that the characters are wearing bowler hats. There's the question of whether or not baseball caps or trucker's hats might also be used.

"Hats are language. While the language is spewing from our mouths - all this other language is going on."

Naturally, all works of art are open to interpretation and Irwin clearly expresses that he makes no claim to having a definitive understanding of his subject's creations. This is very much a personal reaction as seen through his personal lens, inspiring us all to fearlessly use our own personal lenses when approaching challenging art.

Reader Reviews

Videos